Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Anales de Psicología

versão On-line ISSN 1695-2294versão impressa ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.33 no.2 Murcia Mai. 2017

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.2.240521

Spanish adaptation of the Passion Toward Work Scale (PTWS)

Adaptación española de la Escala sobre Pasión por el Trabajo (PTW)

María José Serrano-Fernández1, Joan Boada-Grau2, Carme Gil-Ripoll3 and Andreu Vigil-Colet2

1 Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC), Barcelona (Spain)

2 Universidad Rovira i Virgili (URV), Tarragona (Spain)

3 Business School EADA, Barcelona (Spain)

ABSTRACT

Passion for work has a great influence on workers' occupational health. Vallerand and his collaborators define two types of passion: harmonious and obsessive. With the first, people feel obliged to carry out an activity but freely decide to do it and do so in harmony with other aspects of their lives. With the second, although the person likes the activity, they feel obliged to take part in it because of internal circumstances that exercise control over them. In this context, our objective was to adapt Vallerand and Houlforfs Passion Toward Work Scale (PTWS) into Spanish. The participants were 513 workers selected through non-probability sampling. We used the FACTOR (version 7.2), SPSS 20.0 and Mplus 6.12 programs. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis (exploratory structural equation modelling) of the PTWS support the two-factor model (harmonious passion and obsessive passion), presenting appropriate reliability and evidence of validity with burnout, irritation, engagement and self-efficacy. The PTW scale and questionnaire are therefore reliable and valid instruments that are suitable for use in Spanish.

Key words: Occupational health; Passion for work; Scales; Spanish adaptation.

RESUMEN

La Pasión por el trabajo tiene una gran influencia en la salud laboral de los trabajadores. Vallerand y sus colaboradores proponen dos tipos de pasión, la armoniosa y la obsesiva. En la primera las personas se sienten obligadas a realizar una actividad, pero libremente deciden hacerla y además se encuentra en armonía con otros aspectos de la vida de la persona. Y en la segunda, aunque a las personas les guste una actividad, se sienten obligados a participar en ella a causa de contingencias internas que los controlan. En este contexto, el objetivo planteado fue la adaptación al castellano de la Escala de Pasión por el Trabajo (PTW) de Vallerand y Houlfort. Los participantes han sido 513 trabajadores, obtenidos mediante un muestreo no probabilístico. Se han utilizado los programas FACTOR (versión 7.2), SPSS 20.0 y Mplus 6.12 En la escala PTW, los resultados del AFC (ESEM) apoyan el modelo de dos factores (Pasión Armoniosa y Pasión Obsesiva), presentando una fiabilidad adecuada e indicios de validez con: Burnout, Irritación, Engagement y Autoeficacia. Las Escala PTW es un instrumento fiable y válido, adecuado para ser usado en castellano.

Palabras clave: Salud laboral; Pasión por el trabajo; escala; adaptación español.

Introduction

The concept of passion has received little attention in the field of psychology, given that those who have studied it have concentrated on motivational aspects. According to Frijda, Mesquita, Sonnemans and Van Goozen (1991), for example, passions are defined as priority objectives with emotionally important results. The passion concept has also been placed in different contexts such as creativity (Goldberg, 1986) and the passion for driving vehicles (Marsh & Collet, 1987). These investigations did not result in much empirical research, and consequently Vallerand et al. (2003) found that almost all the empirical work on passion had been carried out in the field of personal relationships. These authors therefore initiated a new approach towards passion for things and defined it as a strong inclination or desire towards an activity that a person likes (or even loves), an activity they consider to be important in their lives and to which they devote time and energy. It thus becomes something significant in their lives, something they enjoy a great deal and something they spend their time doing. The authors based their work on previous research which had clearly shown that the appreciation of an activity (Deci, Eghrari, Patrick, & Leone, 1994), the energy expended (Emmons, 1999) and love of the task (Csikszentmihalyi, Rathunde, & Whalen, 1993) were associated with the time people invest in these activities.

Vallerand and his collaborators (Vallerand, 2010; Vallerand et al., 2003; Vallerand & Houlfort, 2003; Vallerand, Paquet, Philippe & Charest, 2010; Verner-Filion, Lafreniere, & Vallerand, 2012) put forward a construct of two types of passion. Harmonious passion is the result of internalizing an autonomous activity within the identity of the person in whom it arises, when individuals have freely taken on an activity that is important to them and which does not involve any types of contingency. This kind of internalization gives rise to a motivational force for participating voluntarily in the activity and generates a sense of willingness and personal support for undertaking it. The person feels obliged to perform the activity but decides to do so of their own free will. Hence the activity takes up a significant but not unbearable space in the person's identity and, in addition, is in harmony with other aspects of the person's life. Obsessive passion, on the other hand, is the result of a controlled internalization of the activity. This internalization stems from intrapersonal and/or interpersonal pressure either because certain circumstances such as feelings of social acceptance or self-esteem are linked to the activity, or because the emotion derived from participating becomes an uncontrollable factor. Therefore, even though the individual likes the activity, they feel compelled to participate in it because of these internal circumstances that have control over them. Thus they cannot stop participating in the activity because it exercises control over their person and, over time, takes up a disproportionate space in their identity and comes into conflict with other activities in their life.

The Passion Toward Work Scale (PTWS; Vallerand and Houlfort, 2003; Vallerand et al, 2003) is an instrument in English that consists of 14 items and measures two dimensions of passion (harmonious and obsessive) with 7 items each. A number of studies have explored passionate behaviour in various areas, including sports (Vallerand & Miquelón, 2007), the work (Carbonneau, Vallerand, Fernet & Guay, 2008), internet shopping (Wang & Yang, 2008), internet use (Séguin-Lévesque, Laliberté, Pelletier, Blanchard, & Vallerand, 2003), gambling (Lee, Chung, & Bernhard, 2013), positive psychology (Vallerand & Verner-Filion, 2013) and work (Burke & Fiksenbaum, 2009; Lavigne, Forest, Fernet, & Crevier-Braud, 2012, 2014). The scale has been translated from English into Portuguese (Gonyalves, Orgambídez-Ramos, Ferrao, & Parreira, 2014), and also into Dutch (van der Knaap & Steensma, 2015).

This study aims to analyse three aspects: (1) the internal structure, (2) reliability and (3) indications of the scale's validity.

Method

Participants

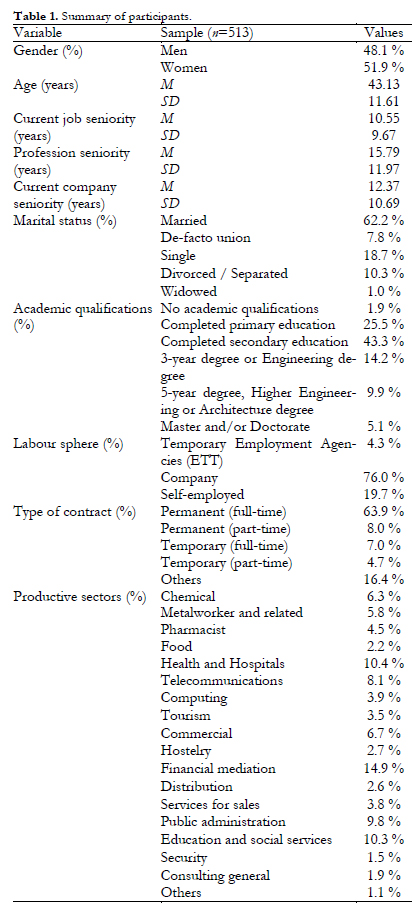

The study participants were 513 workers, employees or self-employed, who were active at the time of data collection. All live in Catalonia (Spain). Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants in the sample.

Instruments

The original English version of the Passion Toward Work Scale (PTWS; Vallerand, & Houlfort, 2003; Vallerand et al, 2003) is made up of 14 items. It was translated into Spanish using translation and "back translation" (Hambleton, Merenda, & Spielberger, 2005; Muñiz & Bartram, 2007) and also the method outlined by Balluerka, Gorostiaga, Alonso and Haranburu (2007). In the English version the items are distributed into two subscales with 7 items each, the first being harmoniouspassion, (α = .70; e.g. "3.- My line of work reflects the qualities I like about myself") and the second obsessive passion (α = .85; e.g. "11.- I am emotionally dependent on my work"). The responses were gathered using a 7-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = totally disagree to 7 = totally agree).

The Spanish version of the Irritation Scale (IS; Merino, Carbonero, Moreno, & Morante, 2006). This is a scale for measuring irritation, which as a concept refers to a state of progressive psychological exhaustion that cannot be alleviated by normal breaks. It consists of 8 items and 2 subscales. The first subscale is "emotional irritation" and is made up of 5 items (α = .86; e.g. "3.- When other people talk to me it irritates me". The second is "cognitive irritation" and is made up of 3 items (α = .87; e.g. "1.- I find it hard to switch off after work"). Responses were gathered on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 = I very much disagree to 7 = I very much agree).

The Spanish version of the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Atienza, Pons, Balaguer, & García-Merita, 2000). This is used to assess satisfaction with life and is a one-factor scale (α = .84) consisting of 5 items (e.g. "2.- So far I have accomplished the things I consider important in life"). Responses were on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree).

The Spanish version of the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE; Sanjuán, Pérez, & Bermúdez, 2000). The GSE is a global construct that applies to the belief that people have about their capacity to properly handle certain situations in everyday life. The scale has only one factor and is made up of 10 items (α = .87; e.g. "8.- I can solve most problems if I make enough effort"). The response format is a 4-point Likert scale. (from 1 = false to 4 = true).

The Spanish version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES; Salanova, Schaufeli, Llorens, Peiró, & Grau, 2000). This is used to assess engagement as a positive state of mind, work-related and characterized by vigour, dedication and absorption. It is a three-factor scale made up of 15 items. The first factor is "vigour", made up of 5 items (e.g. "1.- At work I feel full of energy", α = .80), the second is "dedication", made up of 5 items (e.g. "5.- My work inspires me", α = .92) and the third is "absorption", made up of 5 items (e.g. "8.- I get carried away by my work", α = .75). The response format is a 7-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = totally disagree to 7 = totally agree).

The Maslach Burnout Inventory - General Survey (MBI-GS; Salanova et al., 2000). This scale is used to assess burnout, which is a prolonged response to chronic personal and relational-level stressors at work, determined from known dimensions such as exhaustion, cynicism and professional efficacy. It consists of 15 items (3 subscales). The "exhaustion" factor (α = .87) is made up of 5 items (e.g. "6.- I'm 'burnt out' by my job"), the "cynicism" factor (α = .85) has 4 items (e.g. "9.- I have lost enthusiasm for my work") and "professional efficacy" (α = .78) has 6 items (e.g. "12.- I have accomplished many worthwhile things in my job"). The responses are made on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 = nev-er/not once to 6 = always/ every day.

The Overall Personality Assessment Scale (OPERAS; Vigil-Colet, Morales-Vives, Camps, Tous, & Lorenzo-Seva, 2013) is an instrument that measures personality based on the Big Five model, which tells us that human behaviour depends mainly on five personality traits: extraversion, responsibility, emotional stability, agreeableness and openness to experience. As far as its psychometric properties are concerned, the results show a good fit between the test and the 5-factor structure. The characteristics are: extraversion (α = .86; e.g. "2.- I'm the life of the party"), emotional stability (α = .86; e.g. "32.- I often change moods"), responsibility (α = .77; e.g. "5.- I always keep my word"), agreeableness (α = .71; e.g. "12.- I respect others") and openness to experience (α = .81; e.g. "24.- I like trying out new things"). The scale has 40 items in total, which are answered using a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree).

Finally, we also used a series of correlates to assess evidence of convergent validity (Boada-Grau, Prizmic-Kuzmica, Serrano-Fernández, & Vigil-Colet, 2013; Serrano-Fernández, 2014) in the form of questions that the respondents had to answer. Some of these were existential questions: "Generally speaking, do you feel healthy?", "As regards happiness, how happy are you in your life?" and "How often do you take work home with you?" The response format for these questions was a five-point Likert scale (from 1 = almost never to 5 = almost always). Other questions were answered by specifying a figure or frequency, as in the case of their age (Johnstone & Johnston, 2005), the number of hours they worked during the week (Aziz & Zickar, 2006; Burke & Ng, 2007; Huang, Hu, & Wu, 2010), the nights they had woken up thinking about work matters, postponed personal appointments, and phone calls over the weekend.

Procedure

To obtain the sample we used non-probabilistic sampling, also known as random-accidental sampling. Contact with participants was made in various ways: via the "snowball" method, personal networking and social network researchers. Data were collected and a location agreed by interviewer and participant, generally in the participant's home. The questionnaires were administered in the same order in which they are described in the Instruments section. The administration of the scales was conducted by experienced psychologist researchers. The average time of response for the scales was 45 minutes. The contact response rate from participants was approximately 80%.

Data Analysis

Before proceeding with the statistical analysis we analysed the original 14-item English version of the scale (Valle-rand & Houlfort, 2003). The contents were analysed by 4 psychologist judges, experts on the subject of the manuscript. As a result 5 items of similar content were eliminated. Table 2 shows the valid and the eliminated items, while those that make up the definitive version in Spanish can be found in Table 4 later in the text.

For the present Passion Toward Work Scale (PTWS) (n=513) we used Mplus version 6.12 to carry out the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). This was done using exploratory structural equation modelling (ESEM) (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009). Marsh, Liem, Martin, Morin and Nagengast (2011) put forward ESEM as an alternative to traditional CFA because CFA presents adjustment problems when applied to measures of typical performance. ESEM enabled us to combine the positive aspects of CFA with structural equation models and exploratory factor analysis (EFA), thereby adding more flexibility to all their subcomponents (Marsh, Lüdtke, Nagengast, Morin, & Von Davier, 2013).

ESEM (Morin, Marsh, & Nagengast, 2013) uses a measurement model based on an EFA with its corresponding rotation to which a structural equations model is applied, thus combining the flexibility of EFA with the possibility of obtaining regular fit indices in the structural equations models (Mai & Wen, 2013). It enables analyses to be carried out to confirm the proposed factor structure in a previous EFA, or even more complex analyses to be performed, such as factor invariance studies (Chahin, Cosi, Lorenzo-Seva, & Vigil-Colet, 2010).

The indications of validity of the PTWS were obtained using Pearson correlations and calculated using the SPSS 20.0 program.

Results

The 9 items resulting from the contents analysis (Table 2) were subjected to a CFA (ESEM), which confirmed the factor structure of the original scale in English. All the loadings on the expected factor were statistically significant (p<.01). As the theoretical model assumes that the two factors are not independent, it was decided to use a model with correlated factors. The indices used were the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA ≤ .06), the Compared Fit Index (CFI ≥ .95) and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI > .95). The results showed a good fit for the two-factor model given that the indices (RMSEA = .07; CFI = .97 and TLI ≥ .95) were within optimum levels.

Table 3 shows the mean, the typical deviation, the reliability coefficients and the confidence intervals. As far as the reliability of the factors is concerned, this ranged between .77 and .89. The correlation between the two factors was .46. The total explained variance was 68.25%, distributed between the first factor (50.05%) and the second (18.20%).

Indications of validity were also found in the worker population, where we found correlations between the instrument we present and two demographic variables (age and seniority), as well as thirteen external correlates and six scales (OPERAS, MBI-GS, Irritation, UWES, GSE, SWL). The correlations found are as follows (Table 3):

Harmonious passion is associated positively with extraversion (r =.14, p < .01), emotional stability (r =.25, p < .01), responsibility (r = .20, p < .01), openness to experience (r = .13, p < .01), personal efficacy (r = .28, p < .01), vigour (r = .56, p < .01), dedication (r = .70, p < .01), absorption (r = .57, p < .01) and self-efficacy (r = .28, p < .01). It is associated negatively with burnout (r = -.21, p < .01), cynicism (r = -.35, p < .01), emotional irritation (r = -.12, p < .01) and life satisfaction (r = .33, p < .01).

Obsessive passion correlates positively with seven variables: burnout (r = .13, p < .01), personal efficacy (r = .13, p < .01), emotional irritation (r = .16, p < .01), cognitive irritation (r = .39, p < .01), vigour (r = .42, p < .01), dedication (r = .42, p < .01) and absorption (r = .50, p < .01). It correlates negatively with agreeableness (r = -.09, p < .05) and openness to experience (r = -.13, p < .01).

As regards the external correlates used in our research, harmonious passion correlates negatively with the "number of personal opportunities you lost because you didn't dedicate time to them, because of the time you devote to work" (r = -.10, p < .05) and positively with nine others: "Age" (r = .14, p < .01), "Seniority in the profession" (r = .15, p < .01), "You feel healthy" (r = 0.16, p < .01), "You are happy with your life" (r = .23, p <.01), "Frequency you take work home" (r = .33, p < .01), "Number of nights you have woken up thinking about work issues" (r = .16, p < .01), "Number of overtime hours worked during the year" (r = .10, p < .05), "Days of holidays you've enjoyed" (r = .14, p < .01) and "The number of hours you work a week on average" (r = .09, p < .05).

Obsessive passion is associated positively with the following: "Age" (r = .11, p < .05), "Frequency you take work home" (r = .25, p < .01) , "Number of nights you have woken up thinking about work issues" (r = .29, p < .01), "In social gatherings, the number of times you thought or even told someone that you should be working" (r = .12, p < .01), "Number of personal appointments (doctor visits, meetings - cafés, lunch, dinners - with friends) you arrived for late because you stayed behind working" (r =.14, p < .01), "Number of overtime hours worked during the year" (r =.19, p < .01), "Days of holidays you've enjoyed" (r =.25, p < .01), "Number of hours you work a week on average" (r =.12, p < .01), "If you don't work shifts, the number of Saturday mornings you have worked" (r = .12, p < .01), " If you don't work shifts, the number of Saturday afternoons you have worked" (r =.16, p < .01) and "Number of days you have gone to work whilst feeling ill in the last 12 months" (r =.09, p < .05).

Discussion

The present study examined the factor structure and other psychometric properties of the Passion Toward Work Scale. According to the results, the scale displayed a two-factor structure, appropriate reliability and suitable evidence of validity. The PTWS is an instrument that enables us to evaluate passion for work as a strong inclination towards or desire for work, where work is an activity that workers like, consider important in their lives and in which they invest time and energy. This is the first time the scale has been presented using a Spanish-speaking sample. The results of the CFA (ESEM), with a heterogeneous sample, support the two-factor model put forward by various authors (Gonyalves et al., 2014; Ho, Wong, & Lee, 2011; van der Knaap & Steensma, 2015; Mageau & Vallerand, 2007; Vallerand & Houlfort, 2003), although with fewer items, 9 instead of 14.

The results of the CFA support the two-factor model and show a satisfactory fit. The indices we obtained display a good fit for the model (TLI= .95; CFI= .97; RMSEA= .07). The first factor, known as harmonious passion, is related to the fact that my work enables me to live all kinds of experiences, that my line of work reflects the qualities I have, my work allows me to carry out other activities in my life, and finally, I like the work I do very much. This factor is made up of four items (numbers 1, 2, 3 and 4) and accounts for 50.05% of the variance. The reliability of this factor is 0.77, standing at the midpoint of the reliabilities found by other authors including Vallerand et al. (2003) in a university student population (.73), Carbonneau et al. (2008) in nonuniversity teachers (0.87), Carbonneau, Vallerand and Massicotte (2010) in francophone Canadian citizens who practice yoga (.75), Lavigne et al. (2014) in non-university teachers (.86), Gonyalves et al. (2014) in Portuguese workers (.70), and van der Knaap and Steensma, (2015) in Dutch workers (.76).

The second factor is obsessive passion and refers to emotional dependence, work and the person's emotional state, obsessiveness with work, the difficulty of keeping the need to work under control, and difficulty in imagining life without work. This factor is made up of five items (numbers 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9). The explained variance is 18.20% and Cronbach's alpha is .89, which is higher than the six mentioned above: .85 (university student population) in Vallerand et al. (2003), .76 (non-university teachers) in Carbonneau et al. (2008), .85 (Canadian citizens) in Carbonneau et al. (2010), .75 (non-university teachers) in Lavigne et al. (2014) , .70 (employed persons) in Gonyalves et al. (2014) and .72 (Dutch workers) in van der Knaap and Steensma, (2015).

As regards the correlation between the two factors, in the Spanish version presented this is r = .46, which is the same as the correlation found by Vallerand et al. (2003) (r = .46). However, it is far higher than those found by Carbonneau et al. (2008) (r = -.14), Carbonneau et al. (2010) (r = .22), Lavigne et al. (2014) (r = -.09) and van der Knaap and Steensma, (2015) (r = .14).

After correlating our instrument with various previous scales and a series of external criteria we found evidence of validity. The harmonious passion factor correlated positively with four scales of the OPERAS (extraversion, emotional stability, responsibility, openness to experience), a subscale of the MBI-GS (personal efficacy), the three scales of the UWES (vigour, dedication and absorption), the self-efficacy scale and satisfaction with life. We found inverse correlations with two subscales of the MBI-GS (burnout and cynicism) and a subscale of irritation (emotional). Other authors such as Carbonneau et al. (2008) measured burnout as the only variable, finding an r = -.63 (p <.01) with harmonious passion. In addition, with Dutch workers van der Knaap and Steensma (2015) find a positive correlation with the overall UWES score (r =.59, p< .001).

The obsessive passion factor correlated positively with two subscales of the MBI-GS (burnout and personal efficacy), the two irritation subscales (emotional and cognitive) and the three UWES subscales (vigour, dedication and absorption). It correlated negatively with OPERAS (agreeableness and openness to experience). A positive correlation was also found between obsessive passion and burnout (r = .38, p <.01) (Carbonneau et al., 2008). With Dutch workers, van der Knaap and Steensma (2015) also find a positive correlation with the overall UWES score (r =.21, p< .05).

As far as the external correlates are concerned, we found direct and inverse associations between the two subscales and the external correlates. Harmonious passion (F1) is directly associated with seven external correlates (e.g., feeling healthy, being happy with life, etc.) and inversely associated with one (personal opportunities lost because of not dedicating time to them). We also found a positive relation between obsessive passion (F2) and ten correlates (e.g. how often you take work home with you, nights you have woken up thinking about work, etc.). And finally, we found positive correlations between the sociodemographic variables and the two factors of the PTWS: age correlated with both factors, and seniority in the profession correlated with harmonious passion (F1).

By way of conclusion, the different analyses we carried out point to the existence of a two-factor structure and displayed appropriate statistical indices (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). The PTWS as an instrument can be quickly applied and is easy to interpret as well as readily comprehensible. In addition, each of the two subscales it comprises can be assessed separately.

As regards its applicability, given the scale's good psychometric properties the information it provides enables us to evaluate and get a better understanding of the expectations and the meaning that each employee gives to their work, contributing to our knowledge of passion for work in various aspects. The results have important practical implications for the sphere of passion for work which should be taken into account in relevant strategic human resources management inside organizations (Boada-Grau & Gil-Ripoll, 2011).

References

1. Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2009). Exploratory structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 16, 397-438. Doi: 10.1080/10705510903008204. [ Links ]

2. Atienza, F.L., Pons, D., Balaguer, I., & García-Merita, M.L. (2000). Psychometric properties of the satisfaction with life scale in adolescents. Psicothema, 12, 314-319. [ Links ]

3. Boada-Grau, J., & Gil-Ripoll, C. (2011). Measure of human resource management practices: psychometric properties and factorial structure of the questionnaire PRH-33. Anales de Psicología, 27, 527-535. [ Links ]

4. Boada-Grau, J., Prizmic-Kuzmica, A.J., Serrano-Fernández, M.J., & Vigil-Colet, A. (2013). Factor structure, reliability and validity of the workaholism battery (WorkBAT): Spanish version. Anales de Psicología, 29, 923-933. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.3.147071. [ Links ]

5. Aziz, S., & Zickar, M.J. (2006). A cluster analysis investigation of workaholism as a syndrome. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11, 52-62. Doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.1.52. [ Links ]

6. Balluerka, N., Gorostiaga, A., Alonso-Arbiol, I., & Haranburu, M. (2007). Test adaptation to other cultures: A practical approach. Psicothema, 19, 124-133. [ Links ]

7. Burke, R.J., & Fiksenbaum, L. (2009). Work motivations, satisfactions and health among managers. Passion versus addiction. Cross-Cultural Research, 43, 349-365. Doi: 10.1177/1069397109336990. [ Links ]

8. Burke, R.J., & Ng, E.S.W. (2007). Workaholic Behaviors: Do Colleagues Agree? International Journal of Stress Management, 14, 312-320. Doi: 10.1037/1072-5245.14.3.312. [ Links ]

9. Carbonneau, N., Vallerand, R. J., Fernet, C., & Guay, F. (2008). The role of passion for teaching in intra and interpersonal outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 977-987. Doi: 10.1037/a0012545. [ Links ]

10. Carbonneau, N., Vallerand, R. J., & Massicotte, S. (2010). Is the practice of Yoga associated with positive outcomes? The role of passion. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 452-465. Doi: 10.1080/17439760.2010.534107. [ Links ]

11. Chahin, N., Cosi, S., Lorenzo-Seva, U., & Vigil-Colet, A. (2010). Stability of the factor structure of Barrat's Impulsivity Scales for children across cultures: A comparison of Spain and Colombia. Psicothema, 22, 983-989. [ Links ]

12. Csikszentmihalyi, M., Rathunde, K., & Whalen, S. (1993). Talented teenagers: The roots of success & failure. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

13. Deci, E.L., Eghrari, H., Patrick, B.C., & Leone, D.R. (1994). Facilitating internalization: The self-determination perspective. Journal of Personality, 62, 119-142. Doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00797.x. [ Links ]

14. Emmons, R.A. (1999). The psychology of ultimate concerns: Motivation and spirituality in personality. New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

15. Frijda, N.H., Mesquita, B., Sonnemans, J., & Van Goozen, S. (1991). The duration of affective phenomena or emotions, sentiments and passions. In K. T. Strongman (Ed.), International review of studies on emotion (pp. 187-225). New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

16. Goldberg, C. (1986). The interpersonal aim of creative endeavor. Journal of Creative Behavior, 20, 35-48. Doi: 10.1002/j.2162-6057.1986.tb00415.x. [ Links ]

17. Gonçalves, G., Orgambídez-Ramos, A., Ferrão, M.C., & Parreira, T. (2014). Adaptation and initial validation of the passion scale in a Portuguese sample. Escritos de Psicología, 7, 19-27. Doi: 10.5231/psy.writ.2014.2503. [ Links ]

18. Hambleton, R.K., Merenda, P.F., & Spielberger, C.D. (2005). Adapting educational and psychological tests for cross-cultural assessment. London: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

19. Ho, V.T., Wong, S.S., & Lee, C.H. (2011). A tale of passion: Linking job passion and cognitive engagement to employee work performance. Journal of Management Studies, 48, 26-47. Doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00878.x. [ Links ]

20. Huang, J-C., Hu, C., & Wu, T-C. (2010). Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the workaholism battery. The Journal of Psychology, 144, 163-183. Doi: 10.1080/00223980903472219. [ Links ]

21. Johnstone, A., & Johnston, L. (2005). The relationship between organizational climate, occupational type and workaholism. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 34, 181-188. [ Links ]

22. Lavigne, G.L., Forest, J., & Crevier-Braud, L. (2012). Passion at work and burnout: A two-study test of the mediating role of flow experiences. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 21, 518-546. Doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2011.578390. [ Links ]

23. Lavigne, G.L., Forest, J., Fernet, C., & Crevier-Braud, L. (2014). Passion at work and workers' evaluations of job demands and resources: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 44, 255-265. Doi: 10.1111/jasp.12209. [ Links ]

24. Lee, C., Chung, N., & Bernhard, B.J. (2013). Examining the structural relationships among gambling motivation, passion, and consequences of internet sports betting. Journal of Gambling Studies, E-publication ahead of print, 1-14. Doi: 10.1007/s10899-013-9400-y. [ Links ]

25. Mageau, G.A., & Vallerand, R.J. (2007). The moderating effect of passion on the relation between activity engagement and positive affect. Motivation and Emotion, 31, 312-321. Doi: 10.1007/s11031-007-9071-z. [ Links ]

26. Mai, Y., & Wen, Z. (2013). Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling (ESEM): An Integration of EFA and CFA. Advances in Psychological Science, 21, 934-939. Doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2013.00934. [ Links ]

27. Marsh, H.W., Liem, G.A.D., Martin, A.J., Morin, A.J.S., & Nagengast, B. (2011). Methodological measurement fruitfulness of exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM): New approaches to key substantive issues in motivation and engagement. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 29, 322-346. Doi: 10.1177/0734282911406657. [ Links ]

28. Marsh, H.W., Lüdtke, O., Nagengast, B., Morin, A.J. S., & Von Davier, M. (2013). Why item parcels are (almost) never appropriate: Two wrongs do not make a right - Camouflaging misspecification with item parcels in CFA Models. Psychological Methods, 18, 257-284. Doi: 10.1037/a0032773. [ Links ]

29. Marsh, P., & Collet, P. (1987). Driving passion. Psychology Today, 21, 16-24. [ Links ]

30. Merino, E., Carbonero, M.A., Moreno, B., & Morante, M.E. (2006). Irritation: Analysis of an instrument to assess stress at work. Psicothema, 18, 419-424. [ Links ]

31. Morin, A.J.S., Marsh, H.W., & Nagengast, B. (2013). Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling (Chapter 10). In G.R. Hancock and R.O. Mueller, (Eds.). Structural equation modeling: A second course. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, Inc. [ Links ]

32. Muniz, J., & Bartram, D. (2007). Improving international tests and testing. European Psychologist, 12, 206-219. Doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.12.3.206. [ Links ]

33. Salanova, M., Schaufeli, W.B., Llorens, S., Peiró, J.M., & Grau, R. (2000). Desde el "burnout" al "engagement": ¿una nueva perspectiva? (From 'burnout' to 'engagement': A new perspective?) Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y las Organizaciones / Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 16, 117-134. [ Links ]

34. Sanjuán, P., Pérez, A.M., & Bermúdez, J. (2000). The general self-efficacy scale: psychometric data from the Spanish adaptation. Psicothema, 12, 509-513. [ Links ]

35. Séguin-Lévesque, C., Laliberté , M. L., Pelletier, L. G., Blanchard, C., & Vallerand, R. J. (2003). Harmonious and obsessive passions for the Internet: Their associations with couple's relationships. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 197-221. Doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb02079.x. [ Links ]

36. Serrano-Fernández, M.J. (2.014). Pasión y Adicción al Trabajo: Una investigación psicométrica y predictiva (Tesis doctoral). Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona. [ Links ]

37. Tabachnick, B.G., & Fidell, L.S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

38. Vallerand, R.J., & Miquelón, P. (2007). Passion for sport in athletes. In S. Jowett and D. Lavallée (Eds.), Social psychology in sport (pp. 249-263). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. [ Links ]

39. Vallerand, R.J., & Verner-Filion, J. (2013). Making people's life most worth living: On the importance of passion for positive psychology. Terapia Psicológica, 31, 35-48. [ Links ]

40. Vallerand, R.J. (2010). On passion for life activities: The Dualistic Model of Passion. In M.P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 97-193). New York: Academic Press. [ Links ]

41. Vallerand, R.J., & Houlfort, N. (2003). Passion at work: Toward a new conceptualization. In D. Skarlicki, S. Gilliland and D. Steiner (Eds.), Social issues in management (pp. 175-204). Greenwich, CT: Information Age. [ Links ]

42. Vallerand, R.J., Blanchard, C., Mageau, G.A., Koestner, R., Ratelle, C.F., Léonard, M., Gagné, M., & Marsolais, J. (2003). Les passions de l'âme: on obsessive and harmonious passion (The passions of the soul: obsessive and harmonious passion). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 756-767. Doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.756. [ Links ]

43. Vallerand, R.J., Paquet, Y., Philippe, F.L., & Charest, J. (2010). On the role of passion in burnout: A process model. Journal of Personality, 78, 289-312. Doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00616.x. [ Links ]

44. van der Knaap, M., & Steensma, H. (2015). Research note: Validation of the Dutch Passion Scale, based on the Dualistic Model of Passion. Gedrag & Organisatie, 28, 46-60. [ Links ]

45. Verner-Filion, J., Lafrenière, M.A.K., & Vallerand, R.J. (2012). On the accuracy of affective forecasting: The moderating role of passion. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 849-854. Doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.01.014. [ Links ]

46. Vigil-Colet, A., Morales-Vives, F., Camps, E., Tous, J., & Lorenzo-Seva. U. (2013). Development and validation of the Overall Personality Assessment Scale (OPERAS). Psicothema, 25, 100-106. Doi: 10.7334/psicothema2011.411. [ Links ]

47. Wang, C.C., & Yang, H.W. (2008). Passion for online shopping: The influence of personality and compulsive buying. Social Behavior and Personality, 26, 693-706. Doi: 10.2224/sbp.2008.36.5.693. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

María José Serrano-Fernández.

Facultad de Psicología i ciencies de feducació.

Universitat Oberta de Catalunya.

08035 Barcelona (Spain).

E-mail: mserranofe@uoc.edu

Article received: 25-10-2015;

revised: 13-04-2016;

accepted: 05-09-2016