Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Anales de Psicología

versión On-line ISSN 1695-2294versión impresa ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.33 no.3 Murcia oct. 2017

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.3.276541

Sexual satisfaction among young women: The frequency of sexual activities as a mediator

Satisfacción sexual en mujeres jóvenes: Frecuencia de las actividades sexuales como mediadora

Adelaida I. Ogallar Blanco1, Débora Godoy Izquierdo1, Ma Luisa Vázquez Pérez1,2 and Juan F. Godoy1

1 University of Granada (Spain).

2 University of Jaén (Spain).

This research was supported by the financial assistance provided to the "Psicología de la Salud/Medicina Conductual" Research Group (CTS-0267) by the Consejería de Innovación, Ciencia y Empresa, Junta de Andalucía (Spain). We are grateful to all those who made this study possible.

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study is to analyze the relationship among several social-cognitive predictors of sexual behavior (beliefs, knowledge, attitudes and values), sexual behaviors, the frequency of sexual activities and different dimensions of sexual satisfaction (individual/with the partner and current/desired). A mixed-method study was conducted. The data were collected using a semi-structured interview specially designed for this study, which was administered to 14 to 20 years old young women. Correlation analyses revealed that the expected direct associations between the explored social-cognitive predictors, sexual behavior and sexual satisfaction were not established, so we examined possible indirect effects. The results of the mediational model that better fitted the data indicated that sexual behavior is related with (current) sexual satisfaction, not only directly but also indirectly, through the frequency of sexual activities in a (probable) effect of partial mediation. These findings have interesting applications in terms of sexual education and sexual health promotion among young women.

Key words: Sexuality; sexual satisfaction; sexual behaviors; sexual activities; frequency; mediation; sexual health; young women.

RESUMEN

El objetivo del estudio fue analizar la relación entre varios predictores social-cognitivos del comportamiento sexual (creencias, conocimientos, actitudes y valores), las conductas sexuales, la frecuencia de actividades sexuales y diferentes dimensiones de la satisfacción sexual (individual/de pareja y actual/deseada). Para ello se utilizó un paradigma mixto de investigación. Para recabar los datos se diseñó una entrevista semiestructurada que fue administrada a mujeres jóvenes de entre 14 y 20 años. El análisis de correlaciones indicó que no se establecen las relaciones directas esperadas entre los predictores social-cognitivos, la conducta y la satisfacción sexual, por lo que se exploraron posibles efectos indirectos. Los resultados del modelo de mediación que mejor se ajusta a los datos revelaron que los comportamientos sexuales se asocian a la satisfacción sexual (actual) de forma directa e indirecta a través de la frecuencia con que se practican las actividades sexuales en un (probable) efecto de mediación parcial. Estos hallazgos tienen interesantes aplicaciones prácticas en términos de educación sexual y promoción de la salud sexual en mujeres jóvenes.

Palabras clave: Sexualidad; satisfacción sexual; conductas sexuales; actividades sexuales; frecuencia; mediación; salud sexual; mujeres jóvenes.

Introduction

Sexual health has received increasing attention in recent decades. The focus has been not only on avoiding or treating but also on achieving the highest possible level of well-being, quality of life, and sexual pleasure or satisfaction. Sexual satisfaction is a central subjective and psychological component of sexual experience, and its nature and relationship with other variables have rarely been explored (Bridges, Lease & Ellison, 2004), particularly in people without physical or psychological illnesses, sexual disorders or risk behaviours.

Moreover, sexual satisfaction is essential for well-being. Numerous studies have demonstrated the relationship between a satisfactory sexual life and higher ability to love, satisfaction and adjustment in intimate relationships, selfesteem, physical and mental health, quality of life, emotional satisfaction, happiness, and satisfaction with life (e.g., Stephenson & Sullivan, 2009; Carrobles, Gámez-Guadix & Almendros, 2011). The impact that sexual satisfaction has on all these well-being-related variables justifies research aimed at establishing its determinants, such as communication with the partner (Babin, 2012; Montesi et al., 2013), attachment styles and/or insecurity (Brassard, Dupuy, Bergeron & Shaver, 2015; Stephenson & Sullivan, 2009), and sexual frequency (Muise, Giang & Impett, 2014; Schoenfeld, Loving, Pope, Huston & tulhofer, 2016), among others.

Most studies exploring the determinants of sexual satisfaction have focused on variables related to a relationship with a partner (Khoury & Findlay, 2014; Péloquin, Brassard, Delisle & Bédard, 2013). However, other researchers (e.g., Christopher & Sprecher, 2000; Stephenson & Sullivan, 2009) stress the relevance of understanding the determinants of individual sexual satisfaction, as well. In spite of the influence that knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and values related to sexuality have on sexual behaviour, and in spite of the fact that, presumably, the relationship between these variables and the behaviour should have an influence on sexual satisfaction, there is a lack of studies focused on the predictive capacity of these variables on sexual satisfaction or pleasure, although there are some studies that investigate the interactions between these variables. For example, Li et al. (2013) investigated the relationship between knowledge about HIV and positive and flexible attitudes towards sexual health, and found a positive correlation between the former and preventive sexual behaviour. Kaptanoğlu, Süer, Diktaş & Hınçal (2013) emphasized in their study the importance of adolescentsf knowledge, attitudes and behaviours in controlling the incidence of sexually transmitted diseases.

The stage of adolescence and youth has received much more attention in the research on human sexuality compared to other life stages because health and well-being at these ages are more likely to be compromised by health threats such as unwanted pregnancies and HIV/AIDS or other sexually transmitted infections than at any other age (Sommer & Mmari, 2015). However, the attention given to younger age groups may be the consequence of a pervasive negative conception of sexuality, in which risks and dysfunctions are more relevant than positive aspects such as well-being and personal development. This is especially relevant in the case of women. For this reason, almost all studies on sexuality in adolescents and young adults focus on prevention (of risky behaviours, diseases, pregnancies, interpersonal problems, etc.) instead of on health promotion (Yago-Simon, 2015; Bahamón Muñetón, Vianchá Pinzón & Tobos Vergara, 2014; Ramiro et al., 2014).

All of these investigations are important, especially considering, for example, that Spain currently has one of the highest HIV prevalence rates in the EU (Espada, Morales, Orgilés, Piqueras & Carballo, 2013) and that the rate of voluntary interruptions of pregnancy among women up to 24 years is 26.5 per 1,000 women (Ministerio de Salud, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad, data for 2014). Although such data is alarming, the effectiveness of the many preventive and therapeutic interventions that have been developed to date should be appreciated. In contrast, research and interventions on sexual health promotion, including those aimed at improving levels of sexual satisfaction and well-being, have been scarce.

Thus, interventions are needed that focus on the development of sexually healthy values, attitudes, beliefs and knowledge that could form the basis of healthy and satisfying sexual behaviours in early adulthood and beyond. A necessary first step is to determine the variables that should be approached in such interventions because of their direct or indirect relationship with sexual satisfaction.

In an attempt to study human sexual experience from a positive perspective, the present study on sexuality in adolescent and young women aims to explore the determinants of sexual satisfaction. In doing so, both individual socialcognitive variables, namely knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and values, and interpersonal variables, such as the type of sexual behaviours and frequency of sexual activities, were considered. Moreover, individual sexual satisfaction and sexual satisfaction with the partner, both at their actual and desired levels, were assessed. Because to our knowledge there is no measurement tool encompassing all of the above-mentioned variables, a semi-structured interview, which was fully fitted to the study population, was developed and applied. It was decided to conduct a mixed-method research that allowed both the use of this interview as a method for collecting data on the experiences (preferences, opinions, likes, concerns, needs, etc.) of young women in relation to sexuality (qualitative methodology), and the analysis of possible direct and indirect causal relationships, specifically mediation effects, among the psychosocial determinants included in the study and sexual satisfaction (quantitative methodology) (e.g., Pelto, 2015).

Thus, the objective of this study was two-fold. It sought to explore a) the participants' knowledge, attitudes, values and beliefs; b) sexual behaviours; and c) individual and withthe- partner sexual satisfaction, in both actual and desired dimensions. The study also sought to analyse the possible direct and indirect causal relationships among these variables, addressing specifically the mediating effect of frequency of sexual activities in the relationship between sexual behaviour and sexual satisfaction.

Method

Participants

Forty-eight young Spanish women, aged 14 to 20 years (M = 18.31, SD = 1.86), voluntarily participated in this study. Of them, 70.8% were born or living at the time of the study in a province in the south of Spain (Granada), 16.7% were from other Andalusian provinces, and the remaining 12.5% were from other geographical locations across the nation. All of the participants were Caucasian, except for two participants (8.3%) who reported themselves to be of mixed-race because one of their parents was of gypsy ethnicity.

None of the participants was married. Among the participants, 72.9% reported having had sexual intercourse. Specifically, 41.7% had sex only within an intimate relationship, compared to 6.3% who had sex only with sporadic sexual partners; 25% indicated both types of sexual partners. The average age of onset of sexual intercourse was approximately 16 years old, and participants reported an average of approximately 5 sexual partners.

Other characteristics of the participants, including their education levels, religious beliefs, sexual experiences and sexual preferences, are shown in Table 1.

Measures

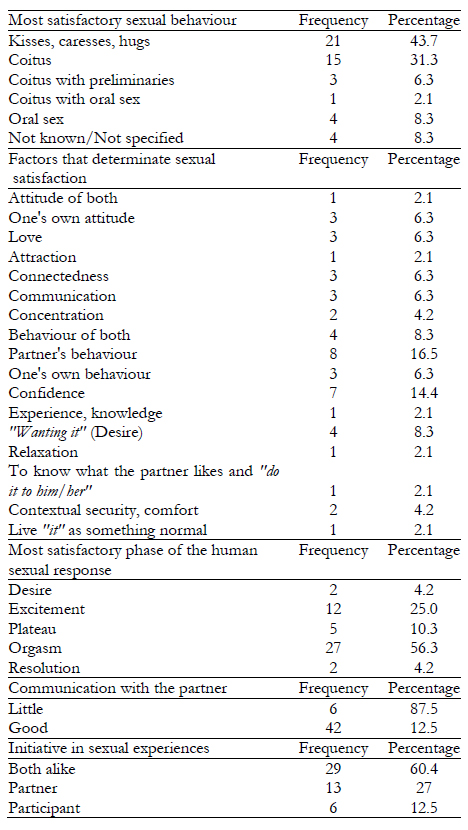

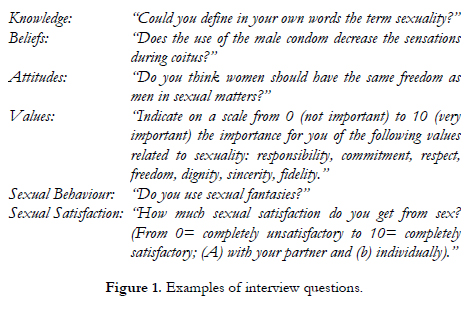

A semi-structured, open-response interview was specially designed by the authors to collect the data. Prior to its use, it was reviewed by field professionals (researchers and experts on human sexuality), and a pilot test with the initial version was conducted with five women to improve the writing and content of the questions. The final interview consisted of 109 questions grouped into 5 sections, of which the following were used in the present study (Figure 1):

(A) Knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and values about sexuality (83 questions):

- Knowledge and beliefs about topics related to sexuality: Meaning of relevant terms (sexuality, contraception, gender, etc.), type and use of contraceptive methods, sexual techniques, risks and diseases, etc. To score each response, levels of correctness (knowledge) and agreement with a positive view of sexuality (beliefs) were considered.

- Attitudes related to sexuality, including affective, cognitive and behavioural components. Their quality was considered in a double continuum from conservative to liberal and from negative to positive.

For the subsequent analyses of these three variables, the qualitative data obtained in the interview were transformed into quantitative data by comparing the participants' responses with a set of previously established responses considered theoretically as more correct (knowledge) or less biased (attitudes and beliefs), according to a series of adjustment criteria established by considering the literature in this regard. The degree of adjustment was assessed on a Likert-type scale from 1 (minimum adjustment) to 5 (maximum adjustment) depending on whether these criteria were met. Thus, answers that best fit the theoretically correct answer were scored with a 5, whereas those with poorer adjustment were scored with a 1. A value of 0 indicated that the participant had not answered the question.

- Values, understood as ethical principles used to guide and judge behaviour. Responses were on a Likert-type scale from 0 = not important to 10 = very important.

For analytical purposes, the variables Knowledge Average, Beliefs Average, Attitudes Average and Values Average were computed. In addition, a combined variable was created by adding the values of the above-mentioned variables and was labelled the KBA Compound (the sum of the averages of knowledge, beliefs and attitudes).

(B) Sexual behaviours (5 questions): Expressions of erotic or affective feelings, including sexual behaviours (individual/ with the partner), use of contraceptive methods and behaviours not strictly sexual but with great importance to sexuality and its expression with a partner (e.g., communication, initiative). The answers were dichotomous (1 = no and 2 = yes), and all scores were added, obtaining the variable Behaviour Summation.

(C) Frequency of sexual activities (5 questions): Frequency of both individual and shared sexual activities, specifically masturbation, hetero-masturbation, oral sex, coitus and kissing/caressing/hugging. The responses were rated on a Likert-type scale from 0 = never to 5 = very frequently. The variable Frequency of Sexual Activities was calculated by adding all frequencies.

(D) Sexual satisfaction (4 questions): Referred to the pleasure or well-being perceived before, during and after performing any kind of sexual behaviour (within any of its physiological, physical and cognitive/emotional dimensions). A differentiation was made between satisfaction obtained through individual activities or behaviours (Individual Satisfaction) and satisfaction obtained in activities with other people, mainly the sexual partner (Satisfaction with the Partner). In addition, a differentiation was made between the actual satisfaction obtained with sexual activities and behaviours (Actual Satisfaction) and satisfaction related to an individually established ideal of sexuality and satisfaction (Desired Satisfaction). In addition, the averages for actual (individual and with-thepartner) and desired (individual and with-the-partner) satisfaction (Actual Sexual Satisfaction and Desired Sexual Satisfaction) were calculated, as well as the average of all the abovementioned satisfaction indicators (Global Sexual Satisfaction).

As for the reliability of the instrument, the degree of agreement between judges was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with a 95% confidence interval, following this procedure: (1) A group of four judges with clinical experience were provided with both the answers to the interview and the adjustment criteria; (2) the answers and the criteria were submitted to the opinion of the judges; (3) the judges were trained in the scoring of responses according to the criteria; and (4) each judge individually scored the 48 interviews. Next, the ICC was calculated, obtaining a value of .96 for both the consistency and the absolute agreement measure.

Procedure

The participants were selected by a non-probabilistic sampling method. Targeted samples were used, including women who volunteered within several community associations and high schools.

The interview duration ranged from 60 to 90 minutes. All participants (or their parents or legal guardians if they were younger than 18) were required to sign an informed consent form. Next, the interview was carried out individually in a classroom or office where the necessary privacy could be guaranteed. Participants had previously been informed about the confidentiality of the information they were to offer and its use solely for scientific purposes. They were also given a brief introduction about the types of questions they would be asked, with guidance that they should respond with the expressions they normally used. In addition, they were told that they could decide to stop the interview whenever they wanted to or leave a question unanswered if they wished to. No participant stopped the interview, and only one chose not to answer one of the questions (for feeling "ashamed" and "not finding the right words").

Permission was granted to record the interview (voice only), guaranteeing the confidentiality of the interview. Nine of the participants declined, so these interviews were not recorded and were registered manually. The recordings were then transcribed verbatim.

Study design and data analyses

This is a descriptive, correlational study with a crosssectional design. A mixed-method research paradigm was deliberately employed, using qualitative methodologies for data collection and qualitative analyses (not presented herein), and quantitative methodologies for statistical analyses of quantitative data. Thus, in this mixed design, qualitative methodology has guided subsequent quantitative analyses (Dures, Rumsey, Morris & Gleeson, 2010; Johnson, Ongwuegbuzie & Turner, 2007).

Preliminary and exploratory data analyses were conducted to detect and correct possible errors in data entry, missing data or outliers. Findings revealed that no atypical values existed. Although the Shapiro-Wilk's test indicated that some variables were not normally distributed, the Levene's test (p > .05) confirmed the homoscedasticity for all variables. Consequently, parametric tests were used for data analyses.

In addition, analyses of indirect effects, specifically mediation, were performed. This analytical strategy establishes the degree to which a predictor variable influences an outcome through one(s) mediator variable(s) in a causal model (Hayes, 2009). Mediation is confirmed when the predictor affects the outcome indirectly through at least one intervening or process variable (Baron & Kenny, 1986; MacKinnon, Fairchild & Fritz, 2007; Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008). To examine possible indirect effects, both simple and multiple parallel mediation analyses were performed using the "PROCESS" macro for SPSS v.22 (Hayes, 2012, 2013), with non-parametric resampling method by bootstrapping (Hayes, 2009; MacKinnon, Lockwood & Williams, 2004; Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008). In addition to simple effects, multiple mediation was analysed because (a) performing simple mediation analyses individually for each potential mediator variable increases the probability of Type I errors when there are two or more mediators, (b) multiple mediation tests the significance of all indirect effects simultaneously, and (c) multiple mediation allows the use of bootstrapping (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

Mediation analyses were performed with both raw and standardized scores to convert the variables to a similar measurement scale (Marquardt, 1980). Standardization of the data has been recommended in mediation analysis (Cheung, 2009) because it allows researchers to obtain standardized indirect effects from 0 to ± 1, which are easily interpretable and comparable to each other. Furthermore, they can be interpreted as an estimate of the effect size, allowing comparisons between studies. The effect size, or standardized indirect effect, provides an indication, independent of the scale of measurement of the variables, of the direction and magnitude or strength of the association between the variables, and in the case of mediation analysis it allows the development of the equation: (standardized) total effect = (standardized) direct effect + (standardized) indirect effect (c = c'+ab). In contrast, because effect size depends directly on the scale of the variables, the (non-standardized) effects estimated from raw data allow only a calculation of their statistical significance.

Because there were missing data for the variable Frequency of Sexual Activities (7 participants indicated that they did not maintain any type of relationship or sexual activity at the time of the study), these cases were omitted from the analyses of indirect effects. Covariates were not included in the mediation analyses given that no strong relationship to be controlled for was found among the study variables.

The level of significance was set at p < .05 for all the analyses.

Results

Table 2 shows the descriptive results for all the variables. For values and attitudes, the mean score was very high; the mean score was moderately high for beliefs and lower for knowledge. Standard deviations for these variables indicate low between-subject variability. Comparatively, the mean for sexual behaviours was high, and the inter-subject variability was remarkable.

The mean for the variable Frequency of Sexual Activities was moderate, and there was high variability among participants. Of the five activities whose frequency was evaluated, activities such as kissing, caressing and hugging were the most frequent, although their mean was not very high. They were followed by coitus, for which the greatest deviations were found, hetero-masturbation, oral sex and, finally, masturbation, with a very low mean.

As for sexual satisfaction, high variability among the participants was found. The highest mean value corresponded to desired sexual satisfaction with the partner, with a very high score, followed by desired individual sexual satisfaction, which was notably lower. The lowest mean values were observed for actual sexual satisfaction with the partner and actual individual satisfaction, with the lowest mean. The remarkable difference between actual and desired levels of satisfaction is most clearly observed when comparing the combined variables Actual Sexual Satisfaction and Desired Sexual Satisfaction.

Pearson's correlation analysis (Table 3) indicated that social- cognitive variables (knowledge, beliefs, attitudes) were generally related to one another in the expected way, except for the Values variable. However, none showed a significant association with sexual behaviours or frequency of sexual activities. Nevertheless, some associations between these variables and satisfaction indicators were found. Women with a higher level of knowledge and more flexible and positive attitudes about sexuality were more satisfied with their individual sexuality and wished to improve their sexuality both individually and with their partners. Interestingly, the Values variable correlated only, but inversely, with desired individual sexual satisfaction.

The variables Behaviour Summation and Frequency of Sexual Activities were positively correlated. In general, they were not associated with isolated and combined sexual satisfaction indicators. The only global indicator with which they were associated was Actual Sexual Satisfaction. Table 3 also shows the specific associations between each type and frequency of sexual activity and the sexual satisfaction indicators.

Moreover, significant positive correlations were observed between actual and desired individual sexual satisfaction, between actual and desired satisfaction with the partner, and in general between these dimensions and the three combined indicators of sexual satisfaction.

The age of the first sexual intercourse was only positively related to the desired individual satisfaction, while the number of partners was not associated with any indicator of sexual satisfaction. Neither variable was associated with Behaviour Summation, Frequency of Sexual Activities or Actual Sexual Satisfaction. Therefore, neither was included as a covariant in the remaining analyses.

Finally, simple mediation analyses (Model 4 of PROCESS) were conducted to explore whether the frequency of sexual activities was a mediating variable in the causal relationship between sexual behaviours (predictor variable) and actual sexual satisfaction (that is, the average of individual and with-the-partner actual sexual satisfaction) (outcome variable), which was the only global dimension of sexual satisfaction with which behavioural and frequency variables were related (Figure 2). Sexual behaviours predicted actual sexual satisfaction directly (marginally significant direct effect), as well as indirectly through frequency (significant indirect effect): The greater the participation in sexual activities, the greater the actual sexual satisfaction. For each unit of increase in the predictor, the mediator increases by .43 units, and for each unit of increase in the mediator, the outcome increases by .24 units; for each unit of increase in the predictor, the outcome increases .28 units when the mediator is controlled for (direct effect), whereas for each unit of increase in the association between the predictor and the mediator, the outcome increases by .11 units (indirect effect). The total effect was also significant, and the full model explained 17% of the variance in Actual Sexual Satisfaction, F(1,39) = 8.162; p = .007. The proportion of the total effect that is a mediated effect (mediated effect/total effect) is 27.7%. Thus, a partial mediation effect is confirmed by which sexual behaviours predict sexual satisfaction both directly (marginal effect) and indirectly through the frequency with which they are performed. Table 4 shows the coefficients and effect sizes of each association, t-values, significance levels and confidence limits of the paths a, b, c' and total and indirect effects.

Other possible models, including the frequency of sexual activities, the KBA Compound variable (summation of knowledge, beliefs and attitudes), and each one of the isolated variables of knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes as mediators, with both simple and multiple (in series and in parallel) mediation, were tested. Findings revealed that either these mediation effects did not prove to be significant or they did not explain an increased amount of the variance of actual sexual satisfaction (results not presented, available upon request).

Discussion

The study of female sexuality in adolescent and young women offers information relevant for the design of other research in the area. It also enables the design of intervention programmes adjusted to the experiences, needs, resources, opinions and interests of this collective, and which are oriented not only towards prevention of risks and illnesses but more importantly towards the promotion of sexual health, including sexual satisfaction, in all its dimensions.

This study analysed the relationship between several social- cognitive predictors of sexual behaviour (beliefs, knowledge, attitudes and values), sexual behaviours, frequency of sexual activities and sexual satisfaction (individual and with-the-partner, actual and desired satisfaction). In terms of levels of knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and values, findings revealed that participants were a fairly homogeneous group. Their beliefs and attitudes towards sexuality were adjusted, positive and flexible. However, participants' knowledge differed from the expected level of cognitive and conceptual competencies on sexuality. These results suggest that these variables could be an excellent focus of interventions. These young women could benefit from actions aimed at increasing their knowledge, which in turn would foster more flexible and open beliefs and attitudes based on appropriate conceptual competencies.

The participants demonstrated sensibly restricted sexual behaviours and low frequency of sexual activities. The activities they performed most frequently are non-coital, which is not surprising given that those are activities all of them can perform (regardless of whether they have had/usually have coital experiences). In addition, contextual constraints (e.g., availability of space for privacy, financial resources) are lower for such activities. The second most frequently performed activity was coitus, followed by hetero-masturbation and oral sex (the latter with a very low frequency), all of which are activities with a partner. The activity they least reported performing is masturbation. These findings parallel the activities they claimed to find as most satisfying: first, kissing, caressing, hugging, etc., and second, intercourse (the remaining activities obtained very low scores). This relationship between sexual satisfaction and affective behaviours, such as kissing, caressing and hugging, is well documented (e.g., Heiman et al., 2011; Hughes & Kruger, 2011; Kruger & Hughes, 2010). However, our findings raise the question of whether very young women practise these activities more often because they are the most pleasurable ones, or whether these activities are the most satisfactory ones because young women find more opportunities to perform them. Knowing the existing relationship between the types of sexual activities considered as more satisfactory and the frequency of performing them could help in understanding sexual satisfaction among young females. Future research should focus on this issue by exploring the reason(s) for performing such activities.

Our findings also revealed that participants seem to gain greater satisfaction in their sexual life with a partner, as compared to more individual-oriented activities: Actual individual sexual satisfaction was not only lower than actual with-thepartner sexual satisfaction, but it also had the lowest scores of all indicators of satisfaction. In addition, divergences between desired individual satisfaction and desired with-thepartner satisfaction were notable. These differences are even more evident when comparing the combined variables Actual Sexual Satisfaction and Desired Sexual Satisfaction: These women not only reported lower rates of individual sexual satisfaction than satisfaction with the partner, but they also seemed to have no special interest in improving the former, whereas they were very interested in improving their sexual satisfaction in shared activities with a partner. Furthermore, most of the factors that, in their opinion, enhance their sexual satisfaction involve another person (Table 1). This indicates that the behaviour, or even the existence, of a partner can exert a great influence on sexual satisfaction among young women. These findings are congruent with those from other studies. For example, Hulbert & Apt (1994, as cited in Bridges et al., 2004) found that women's sexual satisfaction was often closely linked to emotional factors in intimate relationships, while Bridges et al. (2004) showed that women who were comfortable communicating their needs to their partner were more satisfied with their sexual relations than those who felt uncomfortable.

Future research on these issues is warranted. If most of a woman's sexual experiences and satisfaction depend on another person, there will be many limitations for her and her pleasure, both individually and with the partner. In addition, it would be interesting to analyse in the future the relationship between individual satisfaction and individual sexual activities in addition to masturbation, such as the use of fantasies, imagination, etc.

As for the associations between knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and values and sexual behaviours, expected relationship were not found. This challenges theoretical postulates and previous evidence that point to such psychosocial variables as antecedents of behaviour (e.g., Awotidebe, Phillips & Lens, 2014; Kumsa, 2015; Lemer, Blodgett-Salafia & Benson, 2013; Twenge, Sherman & Wells, 2015). Nonetheless, some of these variables were associated with some indicators of sexual satisfaction. This stresses the importance of considering them in interventions aimed at promoting healthy sexuality in young women. Moreover, the greater the behavioural repertoire, the greater the actual individual sexual satisfaction and the overall actual sexual satisfaction, whereas the greater the frequency of sexual activities, the greater the actual withthe- partner satisfaction and the overall actual sexual satisfaction.

After the associations among these variables were explored and the lack of the expected direct relationships was confirmed, the mechanisms that could explain these associations were analysed as an indirect effect (how it operates, or effects of mediation) (Hayes, 2012). This (as well as when it occurs, or effects of moderation, establishing its boundary conditions or contingencies) helps to understand in depth the phenomenon being investigated and gives clues about how that knowledge can be used (Hayes, 2012).

Thus, a series of mediation models was established to predict actual sexual satisfaction (the combination of both individual and with-the-partner satisfaction) by sexual behaviours, frequency of sexual activities, and knowledge, beliefs and attitudes and the general schema that they form (KBA Compound variable). These models were then tested using a non-parametric approach with bootstrapping (Hayes, 2012; Preacher and Hayes, 2004, 2008). For each analysis, resampling of the data was used by creating 5,000 random samples for parameter estimation, guaranteeing the stability of the analysis. Corrected 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the distribution of the ab coefficients obtained by resampling. This procedure requires no previous assumption regarding the distribution of the data, since statistical significance is determined non-parametrically.

The results of the model that best fit the data revealed that sexual behaviours are associated with sexual satisfaction both directly and indirectly through the frequency with which sexual activities are practiced. A greater variety of sexual behaviours and a greater frequency of sexual activities therefore increase sexual satisfaction. Although bivariate correlations had indicated a relationship among these variables, mediation analyses revealed that the relationship was complex. Most likely because of the sample size, although the indirect and total effects were significant, no significant effects were obtained for all the pathways. Specifically, for frequency- satisfaction and behaviour-satisfaction paths, the effect obtained was marginally significant. However, these trends are conceptually reasonable and relevant, as well as consistent with the remaining findings. In the case of the direct effect, a complementary partial mediation effect (Zhao, Lynch & Chen, 2010) in which other possible mediators might also operate would be comparably more plausible, at both conceptual and empirical levels, than a total mediation effect, which would be conceptually unacceptable.

In the case of path b, although Baron & Kenny (1986) indicated that there must be a significant association between the mediator and the outcome variable to assert that there is a mediation effect, recent arguments indicate that this causal effect is not necessary (Zhao et al., 2010) or even not expected (e.g., Mackinnon & Pirlott, 2015). A non-significant effect can be found when the predictor variable is strongly associated with the mediator, which inflates the standard error of path b and makes it difficult to obtain a significant effect. This may be the case in this study. A non-significant effect can also be obtained when other possible intervening variables operate in the relationship between the mediator and the outcome. Therefore, authors such as Zhao et al. (2010) state that "the one and only requirement to demonstrate mediation is a significant indirect effect ab by [...] a bootstrap test" (p. 200), regardless of whether there is a significant direct effect (total or partial mediation).

Despite the effect size, because of the sample size, the findings of the present study should be considered with caution, and they must be confirmed in the future. On the other hand, our findings coincide with previous empirical evidence indicating that sexual frequency predicts sexual satisfaction (e.g., Blair & Pukall, 2014; Greeley 1991, cited in Christopher & Sprecher, 2000; Haavio-Manila & Kontula, 1997; Laumann, Gagnon, Michael & Michaels, 1994; Muise et al., 2014; Schoenfeld et al., 2016).

The findings of this study suggest practical implications of great interest and applicability regarding young women's sexuality. The results obtained suggest that, at the beginning of youth and adulthood, quantity (experiences, diversity, discoveries, etc.) may have at least the same relevance as quality for women to feel sexually satisfied. Therefore, for higher success, interventions on sexual satisfaction should include actions aimed at increasing not only the variety of sexual activities but also their frequency. Similarly, although the relationship between social-cognitive predictors of behaviour and sexual behaviours requires further investigation, it is expected that knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and values will be positively related with sexual satisfaction through their influence on behaviour. Knowing the complex nature of the relationships among all these variables will help in determining the focus of practical interventions.

Despite the contributions of the present study, it suffers from several limitations that should be addressed in the future. The main limitation is the small sample size. The characteristics of data collection and the content of the interview made it considerably difficult to recruit more participants. Consequently, this research should be considered as a preliminary study to guide future research. In addition, this study focused on exploring some aspects of sexuality in adolescent and very young women, and the findings should be interpreted restrictively to this age group, which probably does not share many life conditions with other groups (e.g., women at other ages, single mothers, women with disabilities, men). As a consequence, this study should be replicated with broader and more heterogeneous samples.

Moreover, analytical procedures for testing indirect effects are considerably less potent than other analyses (MacKinnon et al., 2004). Thus, only very strong mediation effects could have been detected in the present study because of the reduced sample size. In addition, other indirect effects should be tested in the future, including moderation, mediated moderation, moderated mediation, or serial or parallel multiple mediation (Hayes, 2012), as well as other possible relationships between variables (e.g., the type models proposed in PROCESS). Similarly, the role of these variables on individual and with-the-partner desired sexual satisfaction should also be explored.

In spite of these limitations, the novelty of the study resides in the use of a mixed methodology in which a first qualitative phase guided the next phase focused on the quantitative analysis of the collected data, with special mention to the analysis of indirect effects. In addition, the richness of the collected information has allowed us to describe and to widely know the sample, and it has helped us in making improvements in the instrument for data collection. Furthermore, this study has also opened new lines of research on a positive view of sexuality and, more broadly, on female sexuality, which has been largely ignored, misinterpreted, neglected or rejected to date (e.g., Bass, 2016; Gavey, 2012; Lamb, 2010; Tolman, 2012).

In conclusion, the frequency of sexual activities contributes significantly to the sexual satisfaction of young women when sexual behaviour is also considered. This study has clarified the direct and indirect causal mechanisms by which sexual behaviour influences sexual satisfaction, and thus it makes a contribution to the cumulative knowledge on the psychosocial correlates of sexual satisfaction in women, at least among young females.

References

1. Awotidebe, A., Phillips, J. and Lens, W. (2014). Factors contributing to the risk of HIV infection in rural school-going adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 11(11), 11,805-11,821. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111111805. [ Links ]

2. Babin, B. A. (2012). An examination of predictors of nonverbal and verbal communication of pleasure during sex and sexual satisfaction. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships, 30(3), 270-292. doi: 10.1177/0265407512454523. [ Links ]

3. Bahamón Muñetón, M. J., Vianchá Pinzón, M. A. y Tobos Vergara, A. R. (2014). Prácticas y conductas sexuales de riesgo en jóvenes. Una perspectiva de género. Psicología desde el Caribe, 31(2), 327-353. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14482/psdc.31.2.3070. [ Links ]

4. Baron, R. M. and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 51, 1,173-1,182. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [ Links ]

5. Bass, T. M. (2016). Exploring female sexuality: Embracing the whole narrative. North Carolina Medical Journal, 77(6), 430-432. doi:10.18043/ncm.77.6.430. [ Links ]

6. Blair, K. L. and Pukall, C. F. (2014). Can less be more? Comparing duration vs. frequency of sexual encounters in same-sex and mixed-sex relationships. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 23(2), 123-136. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2393. [ Links ]

7. Brassard, A., Dupuy, E., Bergeron, S. and Shaver, P. R. (2015). Attachment insecurities and women's sexual function and satisfaction: The mediating roles of sexual self-esteem, sexual anxiety, and sexual assertiveness. Journal of Sex Research, 51(1), 110-119. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.838744. [ Links ]

8. Bridges, S. K., Lease, S. H. and Ellison, C. R. (2004). Predicting sexual satisfaction in women: Implications for counselor education and training. Journal of Couseling & Development, 82, 158-166. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00297.x. [ Links ]

9. Carrobles, J. A., Gámez-Guadix, M. y Almendros, C. (2011). Funcionamiento sexual, satisfacción sexual y bienestar psicológico y subjetivo en una muestra de mujeres españolas. Anales de Psicología 27(1), 27-34. [ Links ]

10. Cheung, M. W. (2009). Comparison of methods for constructing confidence intervals of standardized indirect effects. Behavior Research Methods, 41(2), 425-438. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.2.425. [ Links ]

11. Christopher, S. F. and Sprecher, S. (2000). Sexuality in marriage, dating, and other relationships: A decade review. Journal of Marriage & Family, 62, 999-1,017. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00999x. [ Links ]

12. Dures, E., Rumsey, N., Morris, M. and Gleeson, K. (2010). Mixed methods in health psychology: Theoretical and practical considerations of the third paradigm. Journal of Health Psychology, 14, 1-10. doi: 10.1177/1359105310377537. [ Links ]

13. Espada, J. P., Morales, A., Orgilés, M., Piqueras, A y Carballo, J. L. (2013). Comportamiento sexual bajo la influencia del alcohol en adolescentes españoles. Adicciones, 25(1), 55-62. [ Links ]

14. Gavey, N. (2012). Beyond "empowerment"? Sexuality in a sexist world. Sex Roles,66 (11-12), 718-724. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0069-3. [ Links ]

15. Haavio-Manila, E. and Kontula, O. (1997). Correlates of increased sexual satisfaction. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26(4), 399-419. [ Links ]

16. Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408-420. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360. [ Links ]

17. Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Recuperado de http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf. [ Links ]

18. Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

19. Heiman, J. R., Long, J. S., Smith, S. N., Fisher, W. A., Sand, M. S., and Rosen, R. C. (2011). Sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness in midlife and older couples in five countries. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 741-753. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9703-3. [ Links ]

20. Hughes, S. M., and Kruger, D. J. (2011). Sex differences in post-coital behaviors in long-and short-term mating: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Sex Research, 48, 496-505. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2010.501915. [ Links ]

21. Johnson, R. B., Ongwuegbuzie, A. J. and Turner, L. A. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1, 112-133, doi: 10.1177/1558689806298224. [ Links ]

22. Kaptanoğlu, Süer, Diktaş and Hınçal E. (2013). Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour towards sexually transmitted diseases in Turkish Cypriot adolescents. Central European Journal of Public Health, 21(1), 54-58. [ Links ]

23. Khoury, C. B. and Findlay, B. M. (2014). What makes of good sex? The associations among attachment style, inhibited communication and sexual satisfaction. Journal of Relationships Research, 5(7), 1-11. doi: 10.1017/jrr.2014.7. [ Links ]

24. Kruger, D. J., and Hughes, S. (2010). Variation in reproductive strategies influences post-coital experiences with partners. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, & Cultural Psychology, 4, 254-264. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0099285. [ Links ]

25. Kumsa, D. M. (2015). Factors affecting the sexual behavior of youth and adolescent in Jimma town, Ethiopia. European Scientific Journal, 11(32) Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1750933968?accountid=14542. [ Links ]

26. Lamb, S. (2010). Feminist ideals for a healthy female adolescent sexuality: A critique. Sex Roles, 62(5-6), 294-306. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9698-1. [ Links ]

27. Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, H. J., Michael, R. T.y Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

28. Lemer, J. L., Blodgett Salafia, E. H. y Benson, K. E. (2013) The relationship between college women's sexual attitudes and sexual activity: the mediating role of body image. International Journal of Sexual Health, 25(2), 104-114. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2012.722593. [ Links ]

29. Li, S., Chen, R., Cao, Y., Li J., Zuo, D. y Yan, H. (2013). Sexual knowledge, attitudes and practices of female undergraduate students in Wuhan, China: The only child versus students with siblings. PLoS ONE. 8(9): e73797. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073797. [ Links ]

30. MacKinnon, D. P. y Pirlott, A. G. (2015). Statistical approaches for enhancing causal interpretation of the M to Y relation in mediation analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19(1), 30-43. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1088868314542878. [ Links ]

31. MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J. y Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593-614. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [ Links ]

32. MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M. y Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99-128. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207%2Fs15327906mbr3901_4. [ Links ]

33. Marquardt, D. W. (1980). You should standardize the predictor variables in your regression models. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 75, 87-91. [ Links ]

34. Montesi, J. L., Conner, B. T., Gordon, E. A., Fauber, R. L., Kim, K. H. y Heimberg, R. G. (2013). On the relationship among social anxiety, intimacy, sexual communication, and sexual satisfaction in young couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(1), 81-91. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9929-3. [ Links ]

35. Muise, A., Schimmack, U. e Impett, E. A. (2015). Sexual frequency predicts greater well-being, but more is not always better. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1-8. doi: 10.1177/0146167213490963. [ Links ]

36. Péloquin, K., Brassard, A., Delisle, A. y Bédard, M. M. (2013). Integrating the attachment, caregiving and sexual systems into the understanding of sexual satisfaction. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 45(3), 185-195. doi: 10.1037/a0033514. [ Links ]

37. Pelto, P. J. (2015). What Is So New About Mixed Methods? Qualitative Health Research, 25 (6), 734-745. doi: 10.1177/1049732315573209. [ Links ]

38. Preacher, K. J. y Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS Procedures for estimating effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments y Computers. 36, 717-731. [ Links ]

39. Preacher, K. J. y Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879-891. [ Links ]

40. Ramiro, L., Reis, M., Gaspar de Matos, M., Alves Diniz, J., Ehlinger, V. y Godeau, E. (2014). Sexually transmitted infections prevention across educational stages: Comparing middle, high school and university students in Portugal. Creative Education, 5, 1,405-1,417. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2014.515159. [ Links ]

41. Schoenfeld, E. A., Loving, T. J., Pope, M. T., Huston, T. L. y Štulhofer, A. (2016). Does sex really matter? Examining the connections between spouses' nonsexual behaviors, sexual frequency, sexual satisfaction and marital satisfaction. Archives of Sexual Behavior. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0672-4. [ Links ]

42. Sommer, M. y Mmari, K. (2015). Addressing structural and environmental factors for adolescent sexual and reproductive health in low-and middle-income countries. American Journal of Public Health, 105(10), 1,973-1,981. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302740. [ Links ]

43. Stephenson, K. R. y Sullivan, K. T. (2009). Social norms and general sexual satisfaction: The cost of misperceived descriptive norms. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 18(3), 89-105. [ Links ]

44. Tolman, D. (2012). Female adolescents, sexual empowerment and desire: A missing discourse of gender inequity. Sex Roles, 66(11), 746-757. doi: 10.1007/s11199-012-0122-x. [ Links ]

45. Twenge, J. M., Sherman, R. A. y Wells, B. E. (2015). Changes in American Adults' Sexual Behavior and Attitudes, 1972-2012. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(8), 2,273-2,285. doi: http://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0540-2. [ Links ]

46. Yago-Simón, T. (2015). Gender conditionings and unplanned pregnancies in adolescents and young girls. Anales De Psicología, 31(3), 972-978. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.3.185911. [ Links ]

47. Zhao, X. Lynch Jr., J. G. y Chen, Q.(2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197-206. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/651257. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Débora Godoy-Izquierdo.

Dept. of Personalidad, Evaluación y Tratamiento Psicológico.

Faculty of Psychology.

University of Granada.

Granada (Spain).

E-mail: deborag@ugr.es

Article received: 29-11-2016

revised: 13-12-2016

accepted: 16-12-2016