Introduction

Although the tendency to engage in collective action for a common cause is linked to group identification (Van Zomeren, Postmes, & Spears, 2008), radical action on behalf of one’s group requires more than simply identifying with others and perceiving oneself as part of a community. To characterize individuals who are ready to initiate and engage in extreme progroup behaviors and not merely follow group norms or others’ orders, Swann and colleagues (Swann, Gómez, Seyle, Morales, & Huici, 2009; Swann, Jetten, Gómez, Whitehouse, & Bastian, 2012) proposed the group identity fusion construct. For fused people, their group becomes a personal matter, and in-group members are treated as extended family, especially when common values and other characteristics are highlighted (Swann et al., 2014). The state of identity fusion depicts a feeling of oneness with a group and the merger of personal and social identities. This specific form of alignment with a group is considered stable in time (Swann et al., 2012). Thus, the permeability of the boundary between the personal self and the social self presented by fused persons is unique. It can lead to questions about the characteristics of the self-views of persons who are fused with their social group(s). How do these individuals see themselves in dimensions important to social functioning? Thus, the overall goal of the studies in this article is to extend previous research and examine the relationship between identity fusion and self-construals and traits related to personal and social identity. Specifically, I would like to explore how identity fusion relates to independent and interdepended self-construals, argentic and communal self-stereotyping and verification motives. I believed that focusing on predictors and antecedents of identity fusion contributes to the literature on fusion and group processes.

To portray fused people, to date, researchers have proposed principles of identity fusion theory (for an overview, see Gómez & Vázquez, 2015; Swann et al., 2012). These principles are also the theoretical bases for the reasoning presented in this article. First, the agentic-personal self principle assumes that when a person fuses with a group, he or she does not abdicate his or her personal self, and social identity does not fully guide one’s behavior instead of individual goals and norms. That is, the overlapping of these two identities does not necessarily lead to weakening of personal identity. The actions of highly fused people depend on their personal and social identities, working together and strengthening each other. This first principle is related to the second one, called the identity synergy principle. Because for fused persons personal and group identities are highly interconnected and overlapped, triggering either personal or social self-views should strengthen progroup tendencies. Thus, activating the independent self-construal would have very similar effects as activating the interdependent self-construal. Moreover, this principle suggests that the personal and social identities of fused persons combine synergistically, and they experience a strong feeling of personal agency because the integrity of the personal and social selves. Third, the relational ties principle states that fused persons develop relational ties with others with whom they have direct personal contact (e.g., in small groups such as family, clubs, military units, or tribes) or project relational ties onto large groups (e.g., country). Thus, fused individuals could perceive larger groups of people with whom they have little or no contact as family-like communities. Fourth, the irrevocability principle highlights that identity fusion is stable in time, and once people are fused with a group, the process of de-fusion is time-consuming and difficult to initiate.

In relation to these principles, previous studies have shown that the state of identity fusion is strongly related to progroup behavior, as measured by charitable donations (Swann, Gómez, Huici, Morales, & Hixon, 2010) and by willingness to defend in-group members and be self-sacrificial for their good among students and adults from several countries (Besta, 2014; Besta, Szulc, & Jaśkiewicz, 2015; Gómez et al., 2011a; Swann et al., 2014) and members of communities with links to militant jihad (Atran, Sheikh, & Gómez, 2014). Even ostracism increases endorsement of extreme progroup behavior for the in group among fused persons (Gómez, Morales, Hart, Vázquez, & Swann, 2011b).

Identity fusion is an important predictor of radical progroup actions, but what triggers the state of fusion? Previous research focused on the overlap between the self and the group has shown that experimentally heightened approach motivation is related to stronger inclusion of others in the self (Nussinson, Häfner, Seibt, Strack, & Trope, 2012). In addition, studies testing identity fusion theory have demonstrated that increasing autonomic arousal could intensify the effects of identity fusion (e.g., by rising agency through physical exercise; Swann et al., 2010). Contextual factors have been found to influence fusion. Jong, Whitehouse, Kavanagh, and Lane (2015) showed that shared negative experiences could result in stronger fusion with a group, and shared flow during positive collective gatherings also influence identity fusion with fellow in-group members (Zumeta, Basabe, Wlodarczyk, Bobowik, & Páez, 2016). Regarding the motivational factors that influence the behaviors and attitudes of fused individuals, they are especially motivated by self- and group verification strivings because fused individuals regard the personal and social selves as one. Researchers (Swann et al., 2009) have shown that fused persons display compensatory self-verification strivings aimed at reaffirming their relation to the group (e.g., through the willingness to fight for in-group members) when either their social or personal identity is challenged.

These study results emphasized the agency- and community-oriented aspects of fused individuals’ behaviors. Nevertheless, thus far, no published studies have directly explored whether fused people are characterized by traits and self-construals related to personal agentic self-stereotyping, independent self and communal self-stereotyping, or the interdependent self. The studies presented in this article focus on characteristics related to self-concepts and their role in predicting identity fusion. I assumed that if the personal and social selves of fused persons were strongly interconnected, then the traits related to the interdependent self-construal would more strongly correlate with identity fusion when the personal self is also strong and vivid. In other words, people with the strongest identity fusion would describe themselves as highly independent and interdependent (or agentic, goal-oriented and communal, other-oriented). The personal agentic self would serve as a moderator of the relationship between the interdependent self-construal and identity fusion, and would amplify the strength of this relation. People who are interdependent would see themselves as especially strongly fused with a group when they perceived themselves as independent as well. Merely communal traits or a robust interdependent self is not enough to characterize fused people; the interdependent self and the independent self must be developed.

To strengthen the generalizability of the results, the studies were based on three theoretical approaches that can serve as pathways for understanding the self-concept and self-description of fused individuals. The first theoretical approach is based on independent and interdependent self-construals (Singelis, 1994). Self-construal refers to the grounds of self-definition, how a person understands himself or herself in relation to other people (Cross, Hardin, & Gercek-Swing, 2011; Pilarska, 2014). Self-construal can affect various aspects of social and personal functioning, for example, strategies for coping with stress (Kwiatkowska et al., 2014) or subjective well-being (Pilarska, 2014). In general, people with a strongly developed interdependent self perceive themselves as part of a larger group and as connected to others, and their self-descriptions include traits and characteristics that highlight group membership and closeness to family, friends, and other members of their social networks (Cross et al., 2011; D’Amico & Scrima, 2016). The interdependent self-construal is also related to cooperation. For example, priming with the interdependent self (vs. independent) resulted in higher levels of cooperation in give-some social dilemmas (Utz, 2004). Previous results have also shown that the relational-interdependent self-construal is related to positive evaluations of conflict outcomes when a decision favors a close other (vs. self) and that those with a high-relational interdependent self-construal exhibit a tendency to integrate their interests with those of close others (Gore & Cross, 2011). In the studies in the present article, which follow original work by Singelis (1994), the interdependent self and the independent self are considered two dimensions and not two ends of one dimension (thus two separate scales for measuring the self-construals were used). As Pilarska (2014) stated, individuation related to independent self-construal and affiliation, important for interdependent self-construal, encompasses universal human motives. Thus, each individual might have developed independent and interdependent self-construals, and their cognitive accessibility and influence on one’s social functioning are specific to the individual.

The theory of identity fusion links the state of fusion not only with perceptions of common interests with fellow in-group members but also with a tendency to initiate actions on behalf of the group. Thus, the main goal of the present analyses was to test hypothesis 1: Fused individuals with overlapping personal and group identities view themselves as community oriented and independent. That is, I proposed that a strong interdependent self-construal is related to identity fusion when the independent self is also strongly developed, and this independent self-construal moderates the relation between the interdependent self and identity fusion. In this view, identity fusion is not simply the effect of a high affiliation motive or the prevalent interdependent self.

The second underlying theoretical framework of the current studies is previous work on two main dimensions of social perception: agency or competence and communion or warmth (Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, 2008; Wojciszke, Abele, & Baryla, 2009). In light of these theories, communal traits are related to behaviors that serve one’s community (e.g., helping others, caring, being ready to compromise; see, for example, Wojciszke & Szlendak, 2010), and the agency dimension is related to individual efficacy and the potential to achieve goals (e.g., the traits skillful and intelligent; see Cuddy et al., 2008). Regarding personal and group identity fusion, identity fusion theory suggests that people with identity fusion might be not only community oriented and not only agentic but also both at the same time. For example, strongly fused people are inclined to endorse progroup action when either the personal or the social self is salient (Swann et al., 2009). Swann et al. (2009) also argued that fused individuals are those who act as agents for the group, and their individual agency is tied to progroup behavior, and relation between identity fusion and personal agency has been shown (Besta, Mattingly, & Błażek, 2016). Research results suggest that experimentally heightening fused participants’ feeling of agency increases their caring for the community as measured by prosocial behaviors toward in-group members (Swann et al., 2010). The importance of examining the interplay between agency and communion among fused individuals is also clear in recent developments in identity fusion theory. Researchers have emphasized that “although strongly fused people align themselves with the collective, they nevertheless retain an agentic personal self and cultivate close ties to fellow group members as well as to the collective category” (Swann & Buhrmester, 2015, p. 53). The interplay between agency self-stereotyping and communal self-stereotyping plays a role in characterizing identity fusion. As researchers have shown that these two dimensions of social perception could be also used to measure one’s self-assessment and self-stereotyping (e.g., Laurin, Kay, & Shepherd, 2011), the self-ascribed trait type (agentic and communal) was included in the current studies. Therefore, hypothesis 2 was proposed: The agentic self-description moderates the relationship between one’s communion and identity fusion in such a way that this relation is stronger when self-perceived agency is also strongly developed.

The third area of research is related to self-verification and self-enhancement strivings (Seih, Buhrmester, Lin, Huan, & Swann, 2013; Swann, Stein-Seroussi, & Giesler, 1992). I concentrated on the tendencies toward collective and personal verification (Swann, Polzer, Seyle, & Ko, 2004) and whether people who are motivated especially strongly by both motives are also more likely to be fused with groups important to the individuals. Previous studies revealed the tendency for fused people to act on behalf of the group in reaction to identity threats. Interestingly, threats to personal and group identities had similar effects, with an increased tendency to engage in radical progroup action (Swann et al., 2009). These results suggest that the motivations for self- and collective verification are strong among fused individuals. Based on these results, I propose hypothesis 3: People exhibit the strongest identity fusion when motives for self- and group verification are strongly developed. That is, the relationship between the tendency to verify oneself on the group level of self-description and identity fusion is moderated by self-verification striving, and this relation is stronger at the highest level of self-verification.

Overview of Current Studies

Four studies were conducted to test the three hypotheses that identity fusion is related to the interaction between independent and interdependent self-construals (hypothesis 1; studies 1, 2, and 4), agentic and communal self-stereotyping (hypothesis 2; studies 3 and 4), and self- and collective verification (hypothesis 3; studies 3 and 4). In all studies, the measures of the variables were part of a larger survey. In study 1, participants were asked to indicate their relationship with two groups by filling out scales of identity fusion with country and gender group and measures of the independent self and the interdependent self. In study 2, participants were asked to think and write about their most important social group, other than their family, close friends, and country, and to indicate how fused they were with this group. Before doing this, the participants filled out the self-construal scale. In study 3, participants again answered questions related to their identity fusion with the social group important to them. This study included measures of agentic and communal self-description and motivation to engage in self- and group verification. Finally, in study 4, all hypotheses were tested among people involved in a natural social group (active football fans).

Study 1

Methods

Participants. Polish adults voluntarily participated in an online study. In all, 244 individuals were recruited from among registered users of a research panel (125 women; M age = 36.05, SD = 12.06; age range: 18-64).

Procedure and materials. The questionnaire was administered online. After a short paragraph that introduced the study, participants were asked to provide demographic information and answer questions on scales that included measures of interdependent and independent self and identity fusion with country and gender.

Independent and interdependent self. To assess self-construal, I used the shorter version (Kwiatkowska et al., 2015) of the original self-construal scale (Singelis, 1994). Five items each measured the interdependent self and the independent self (e.g., “My happiness depends on the happiness of the person closest to me,” “Usually I agree with what others want to do, even if I’d rather do something else,” “I behave the same way no matter who I am with,” “In many ways, I like to be unique and different from those close to me”). Participants responded using a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s α was .63 for the interdependent self-construal and .64 for the independent self-construal.

Identity fusion . To assess the level of fusion between personal and group identities, I used the Polish version (Besta, Gómez, & Vázquez, 2014; Jaśkiewicz & Besta, 2014) of the seven-item identity fusion scale (Gómez et al., 2011b). The feeling of unity with one’s country (“I am one with my country,” “I feel immersed in my country,” “I have a deep emotional bond with my country,” “My country is me,” “I would do more for my country than any of the other group members would,” “I am strong because of my country,” “I make my country strong”) and with gender (e.g., “I feel one with my gender”) were measured separately. Participants responded using a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). The scales showed good reliability; Cronbach’s α was .93 for the country version and .95 for the gender version.

Results and discussion

Preliminary analysis. The mean results were 4.25 (SD = 1.18) for identity fusion with country and 4.21 (SD = 1.13) for gender fusion. Preliminary correlation analyses showed that all variables were correlated, and only the relation between the independent and interdependent self-construals did not reach statistical significance (r(242) = .10, p = .11). The analyses revealed statistically significant but small correlations of self-construal with fusion with country (independent self: r(242) = .14, p = .03; interdependent self: r(243) = .13, p = .04) and with fusion with gender (independent self: r(242) = .16, p = .01; interdependent self: r(242) = .18, p = .005).

Self-construals as predictors of identity fusion. To examine hypothesis 1, which assumed the interaction effect of the independent self and the interdependent self on identity fusion, I conducted moderation analyses based on 10,000 bootstrap samples using the Process macro, model 1 (Hayes, 2013). First, I examined fusion with one’s gender. I included the interdependent self as the predictor, identity fusion as the dependent variable, and the independent self as the moderator of the relation between the interdependent self and identity fusion. As expected, and in support of hypothesis 1, a moderator effect of an independent self-construal on the relation between the interdependent self and identity fusion emerged, with a statistically significant interaction between the interdependent self and the independent self (beta coefficient: 0.32, SE = 0.08, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval entirely above zero: 0.15-0.48). Moderation analyses revealed that the relationship between the interdependent self and identity fusion was stronger at a high independent self (1 SD above the mean, beta coefficient: 0.45, SE = 0.11, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval entirely above zero: 0.24-0.66) than at a medium level (beta coefficient: 0.21, SE = 0.09, p = .02, bias-corrected confidence interval above zero: 0.04-0.39) or a low level (1 SD below the mean, beta coefficient: -0.03, SE = 0.11, p = .82, bias-corrected confidence interval cutting 0: -0.25 to 0.20) (see Figure 1). The overall R2 for the model was 0.11 (F(3,240) = 9.42, p < .001).

Figure 1 Moderator effect between independent and interdependent self-construals in study 1. Low and high results are based on -1 standard deviation and +1 standard deviation from the mean, respectively; identity fusion in the context of gender group.

Similar analyses for fusion with country did not reveal a statistically significant interaction effect (beta coefficient for interaction: 0.11, SE = 0.09, p = .22; the overall R2 for model = 0.04 (F(3,240) = 3.33, p = .02). However, the moderation analyses showed similar patterns of codependence as with fusion with gender. The relationship between the interdependent self and identity fusion was stronger at a high level of independent self (beta coefficient: 0.26, SE = 0.11, p = .03, bias-corrected confidence interval above zero: 0.03-0.48) than at an average level (beta coefficient: 0.17, SE = 0.10, p = .08, bias-corrected confidence: -0.02 to 0.37) or a low level (1 SD below the mean; beta coefficient 0.09, SE = 0.12, p = .47, bias-corrected confidence interval cutting zero: -0.16 to 0.33).

Alternative model of moderation. In study 1 alternative models were also examined, to check if identity fusion might be a significant moderator of the relationship between interdependent and independent self-construal. For fusion with a country there was no significant relation between fusion and independent self, and fusion was not a moderator of tested relationship. Fusion with one’s gender turned out to be significant moderator of the interdependent and independent self relation. Interaction effect fusion x interdependent self was significant with beta coefficient: 0.19, SE = 0.05, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval entirely above zero: 0.09-0.29). Moderation analyses revealed that the positive relationship between the interdependent and independent self was significant among highly fused individuals (1 SD above the mean, beta coefficient: 0.32, SE = 0.09, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval entirely above zero: 0.14-0.49), but not at a medium and low level of fusion (not significant).

Discussion. The results for fusion with country suggested that a strong visceral feeling of belonging to a more extended abstract group (i.e., country) might depend on other factors more than on the self-construal. An alternative model of moderation, although not included in the hypotheses, support the notion that both independent and interdependent self-construals goes hand in hand only when people feel strong visceral adherence to their group. As this was not true for fusion with a country, these results might suggest that other psychological variables could be important in developing feeling of oneness in a context of nation or country.

To test whether the interaction with self-construals is important for the self-description of people strongly fused with smaller, relational groups, study 2 was conducted. In this study, participants declared the strength of their identity fusion with a social group they considered important for their self-definition.

Study 2

Methods

Participants. Polish adults from a sample of registered users of a research panel representative of the population of Polish Internet users were recruited to participate voluntarily in an online study. In all, 164 individuals who followed the instructions and completed all the measures were included in the analyses (92 participants were excluded, as they did not follow the instructions and did not list any social group close to them and important for their self-definition). The sample was diverse, with 83 women included and all age ranges represented (18-24 years old: 20.1%, 25-34: 27.4%, 35-44: 21.3%, 45-54: 16.5%, 55 or older: 14.6%).

Procedure and materials. The questionnaire was administered online. After a short paragraph that introduced the study, participants were asked to provide demographic information and answer questions on the interdependent self and independent self scales. Next, the participants were asked to think about and write the name of the social group closest to them and most important for their self-definition, except for family, close friends, and country. Only individuals who followed these instructions were included in the analyses; those who stated “no such group” or “family” were excluded. After naming this group, participants were asked to answer questions on the identity fusion scale.

Independent and interdependent self. As in study 1, I used the shorter, 10-item version of the original self-construal scale (Singelis, 1994) to assess self-construal (e.g., “My happiness depends on the happiness of those closest to me,” “I behave the same way no matter who I am with” for the interdependent self and the independent self, respectively). Participants responded using a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s α was .54 for the interdependent self-construal and .62 for the independent self-construal.

Identity fusion . To assess the level of fusion between personal and group identity, I used the seven-item identity fusion scale (Gómez et al., 2011b) and measured fusion with the groups provided by participants (e.g., sports club, religious group, coworkers, nongovernment organization; sample item: “I feel one with my group”). Participants responded using a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Reliability was measured with Cronbach’s α, which equaled .89.

Results and discussion

Preliminary analyses. The average result for identity fusion was 4.70 (SD = 0.93). Preliminary correlation analyses showed that all variables were correlated, except for the relation between the independent and interdependent self-construals. As in study 1, this relationship did not reach statistical significance (r(162) = .13, p = .10). Analyses revealed statistically significant correlations between self-construals and fusion with group (independent self: r(162) = .30, p< .001; interdependent self: r(162) = .27, p = .001).

Self-construals as predictors of identity fusion. To test the hypothesis, I conducted moderation analyses based on 10,000 bootstrap samples using the Process macro, model 1 (Hayes, 2013). I included the interdependent self as the predictor, identity fusion as the dependent variable, and the independent self as the moderator of the relation between the interdependent self and fusion. The overall R2 for the model was 0.17 (F(3,160) = 11.15, p < .001). Hypothesis 1 was supported, and a statistically significant interaction effect between the independent and interdependent self-construals on identity fusion emerged (beta coefficient: 0.28, SE = 0.12, p = .02, bias-corrected confidence interval entirely more than 0: 0.05-0.51). Moderation analyses revealed that the relationship between the interdependent self and identity fusion was stronger at a high level of independent self (1 SD above the mean, beta coefficient: 0.42, SE = 0.11, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval of more than 0: 0.21-0.64) than at the mean level (beta coefficient: 0.24, SE = 0.10, p = .03, bias-corrected confidence interval above zero: 0.03-0.44) or a low level (1 SD below mean; beta coefficient: 0.05, SE = 0.15, p = .75, bias-corrected confidence interval cutting zero: -0.25 to 0.34; see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Moderator effect between independent and interdependent self-construals in study 2. Low and high results are based on -1 standard deviation and +1 standard deviation from the mean, respectively.

Alternative model of moderation. In study 2 alternative model was also examined, to check if identity fusion might be a significant moderator of the relationship between interdependent and independent self-construal. As in study 1, when self-construals were also examined, moderation model shows that interaction between fusion and predictor variables was significance, and strength of the relationship between predictor and independent variable was moderated by the level of identity fusion. Interaction effect fusion x interdependent self was significant with beta coefficient: 0.23, SE = 0.07, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval entirely above zero: 0.10-0.37). Moderation analyses revealed that the positive relationship between the interdependent and independent self was significant among highly fused individuals (beta coefficient: 0.25, SE = 0.10, p = .01, bias-corrected confidence interval entirely above zero: 0.06-0.44), but not at a medium level of fusion (not significant). For low fused individuals there was even negative relationship between independent and interdependent self (at the tendency level), with beta coefficient: -0.19, SE = 0.11, p = .08, bias-corrected confidence interval: -0.39-0.02.

Discussion. Results of study 2 supported hypothesis 1. People with the strongest fusion with their close social groups important for their self-description showed the highest level of interdependent and independent self-construals. These results showed that the interdependent self by itself was not enough to describe fused people, and the strongest relation between the feeling of fusion and interdependent self-description emerged at the highest level of independent self-construal. Once again an alternative model of moderation, not included in presented hypotheses, support the notion that both independent and interdependent self-construals are positively related only when people feel strong visceral adherence to their group.

In study 3, I examined whether these interdependencies were confirmed when different self-characteristics, namely, agentic and communal self-description and motives for self- and group verification, were considered.

Study 3

Methods

Participants. As in study 2, Polish adults from an Internet research panel with preregistered users were recruited for an online study, and 166 individuals who followed the instructions and completed all the measures were included in the analysis (110 participants were excluded, as they did not list any social group important for their self-definition other than family and friends). The sample included 85 women, and all age ranges were represented (18-24 years old: 17.5.1%, 25-34: 33.1%, 35-44: 22.3%, 45-54: 13.35%, 55 or older: 13.9%).

Procedure and materials. As in previous studies, the questionnaire was administered online. The procedures were similar to those used in study 2. First, participants filled out the scale for agentic and communal self-stereotyping and the measure of desire for self- and group verification. Next, participants were asked to think about and write the name of the social group closest to them, except for their family, close friends, and country. Individuals who did not follow these instructions were excluded from analysis. After providing the name of the group most important to them, participants were asked to answer questions on the identity fusion scale.

Agency and communion. To measure self-description of traits related to agency and communion, I included items based on traits used by Laurin et al. (2011). There were five items for agency self-stereotyping (e.g., “I am . . . self-confident or competent) and five items for communion self-stereotyping (e.g., “I am warm or caring”). Participants responded using a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Both scales showed acceptable reliability, with Cronbach’s α of .83 for agency and .77 for communion.

Self- and collective verification. To measure the desire to verify self-description and participants’ group-related traits, a four-item scale was used (Wiesenfeld, Swann, Brockner, & Bartel, 2007). Participants responded using a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Two items evaluated the desire for self-verification (“I want others to understand who I am,” “I want others to see me as I see myself”; r = .52), and two items evaluated the desire for collective verification (“I want others to really understand my feelings about the group”, “I want others to recognize that I am absolutely committed to the group”; r = .70).

Identity fusion . I used a seven-item identity fusion scale (Gómez et al., 2011b) to measure fusion with the group indicated by participants, who responded on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Reliability was measured with Cronbach’s α, which equaled .93.

Results and discussion

Preliminary analyses. The average result for identity fusion was 4.74 (SD = 1.02). Preliminary zero-order correlation analyses showed that identity fusion was related to all variables (agentic self-stereotyping: r(164) = .51, p < .001; communal self-stereotyping: r(164) = .32, p = .001; self-verification: r(164) = .40, p < .001; collective verification: r(165) = .45, p = .001).

Agentic and communal self-stereotyping and identity fusion. To test hypothesis 2, which assumed a statistically significant interaction effect between agency and communion self-ascribed traits on identity fusion, I conducted a moderation analysis based on 10,000 bootstrap samples using the Process macro, model 1 (Hayes, 2013). I included communal self-stereotyping as the predictor and agency as the moderator of the relation between communal traits and identity fusion. The overall R2 for the model was 0.30 (F(3,162) = 23.24, p < .001). Hypothesis 2 was supported, and a statistically significant interaction between agency and communion on identity fusion emerged (beta coefficient: 0.23, SE = 0.08, p = .003, bias-corrected confidence interval were entirely above zero: 0.08-0.39). Similarly to previous studies on self-construals, the moderation analyses revealed that the relationship between communion self-description and identity fusion was stronger at high levels of agentic self-stereotyping (1 SD above the mean, beta coefficient 0.32, SE = 0.12, p = .007, bias-corrected confidence interval: 0.09-0.55) than at the average level (beta coefficient: 0.11, SE = 0.10, p = .25, bias-corrected confidence interval: -0.08 to 0.30) and low level (1 SD below the mean, beta coefficient: -0.10, SE = 0.12, p = .42, bias-corrected confidence interval cutting zero: -0.33 to 0.14; see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Moderator effect between agentic and communal self-description in study 3. Low and high results are based on -1 standard deviation and +1 standard deviation from the mean, respectively.

Results of study 3 supported hypothesis 2. People with the strongest fusion with their close social groups described themselves as very communal and very agentic.

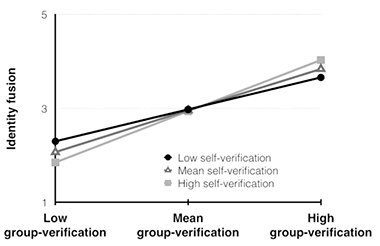

Desire for self- and collective verification and identity fusion. To test hypothesis 3, which assumed statistically significant interaction effects of the desire to verify self-concept on identity fusion at the personal and group levels, I conducted a second moderation analysis based on 10,000 bootstrap samples using the Process macro, model 1 (Hayes, 2013). I included desire for collective-level self-verification as the predictor (e.g., desire to be seen as a member of the group as one sees oneself), identity fusion as the dependent variable, and self-verification (e.g., expectations that others will see one’s specific personal traits the same way one does) as the moderator of the relation between group verification and identity fusion. The overall R2 for the model was 0.24 (F(3,162) = 17.38, p < .001). Hypothesis 3 was supported, and a statistically significant interaction effect between self-verification and collective verification on identity fusion emerged (beta coefficient: 0.13, SE = 0.05, p = .01, bias-corrected confidence interval: 0.03-0.23). The moderation analyses revealed that the relationship between group verification and identity fusion was stronger at high levels of self-verification (1 SD above the mean, beta coefficient 0.49, SE = 0.12, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval above zero: 0.26-0.71) than at average levels (beta coefficient: 0.35, SE = 0.10, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval: 0.16-0.55) and low levels (1 SD below the mean; beta coefficient 0.22, SE = 0.11, p = .04, bias-corrected confidence interval: 0.01-0.43) (see Figure 4).

Figure 4 Moderator effect between desire for self- and group verification in study 3. Low and high results are based on -1 standard deviation and +1 standard deviation from the mean, respectively.

Alternative models of moderation. In study 3 alternative models were also examined in order to check if identity fusion might be a significant moderator of the relationship between (1) agentic and communal self-stereotyping and (2) collective and self-verification. In all these moderation models interaction between fusion and predictor variable did not reach significance, and strength of the relationship between predictors and independent variables was similar among low, average and highly fused individuals.

Discussion. The results showed that hypothesis 3 was supported. People with the strongest fusion with their close social groups described themselves as very communal and very agentic and perceived self- and group verification as important motives guiding the individuals’ behaviors.

Although the results supported hypotheses 1, 2, and 3, studies 2 and 3 focused on fusion with groups specific to every participant. To validate the results of previous studies on people closely related to a single, natural social group (thus examining fusion with the same group for all participants), the final test of the three hypotheses was conducted in study 4 with football fans.

Study 4

Method

Participants. Self-declared Polish football fans participated in the online study. Information about study was posted on websites related to football culture and teams. Only adult participants who were self-declared football fans were included, yielding a total of 796 respondents (92 women; M age = 27.64, SD = 7.87).

Procedure and materials. The questionnaire was administered online, and all the questions were in Polish. First, participants answered questions not related to the present analyses (e.g., questions on football culture, their fan behavior, and team preferences). Next, participants completed the scale for self-construals, agentic and communal self-stereotyping, the measure of desire for self- and group verification, and the scale of personal and group identity fusion (the reference group was other fans of the participants’ teams).

Independent and interdependent self. As in studies 1 and 2, the shorter, 10-item version of the original self-construal scale was to assess self-construals (Singelis, 1994). Participants responded on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s α were .64 for interdependent self-construal and .75 for independent self-construal.

Agency and communion. To measure self-description of traits related to agency and communion, I included items based on traits used by Laurin et al. (2011). Six items assessed agency self-stereotyping (e.g., “I am self-confident or intelligent”), and six items assessed communion self-stereotyping (e.g., “I am warm or sensitive”). Participants responded using a 7-point scale (0 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). Both scales showed acceptable reliability, with Cronbach’s α of .80 for agency and .81 for communion.

Self- and collective verification. To measure the level of self- and group verification, a four-item scale was used, as in study 3 (Wiesenfeld et al., 2007). Participants responded on a 7-point scale (0 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). Two items assessed the desire for self-verification (“I want others to understand who I am,” “I want others to see me as I see myself”; r = .73), and two items assessed the desire for collective verification (“I want others to really understand my feelings about the group,” “I want others to recognize that I am absolutely committed to the group”; r = .82).

Identity fusion . As in previous studies, a seven-item identity fusion scale was used (Gómez et al., 2011b) to measure fusion with the group indicated by participants, who responded using a 7-point scale (0 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). Reliability was measured with Cronbach’s α of .94.

Results

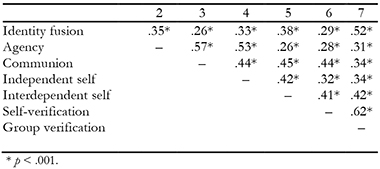

Preliminary analyses. The average result for identity fusion was 3.08 (SD = 1.53). Preliminary zero-order correlation analyses showed that identity fusion was related to all the variables. The strongest relation was with the desire to verify one’s group self-concept (r(794) = .52, p < 0.001) and the weakest with communal self-description r(794) = .26, p < .001 (see Table 1 for detailed information).

Self-construals as predictors of identity fusion. To test hypothesis 1, I conducted a moderation analysis based on 10,000 bootstrap samples using the Process macro, model 1 (Hayes, 2013). I included the interdependent self as the predictor, identity fusion as the dependent variable, and the independent self as the moderator of the relation between the interdependent self and fusion. The overall R2 for the model was 0.20 (F(3,792) = 64.46, p < .001). Hypothesis 1 was supported, and the interaction effect between the independent self and the interdependent self on identity fusion was statistically significant (beta coefficient: 0.13, SE = 0.03, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval entirely above 0: 0.06-0.19). Moderation analyses revealed similar effects as in previous studies. The relationship between the interdependent self and identity fusion was stronger at a high level of independent self (beta coefficient: 0.61, SE = 0.07, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval of more than 0: 0.48-0.75) than at an average level (beta coefficient 0.49, SE = 0.06, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval of more than 0: 0.38-0.61) and a low level (beta coefficient: 0.37, SE = 0.07, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval: 0.24-0.50; see Figure 5).

Figure 5 Moderator effect between independent and interdependent self-construals in study 4. Low and high results are based on -1 standard deviation and +1 standard deviation from the mean, respectively; identity fusion in the context of football fans.

Due to relatively high inter-correlations between some variables employed in this study, we examined also collinerality and partial correlation. Regression analyses show that collinerality, as measured by VIF, for independent self turned out to be 7.71, and for interdependent self = 11.78. Partial correlations between identity fusion and independent self, independent self, and interaction between independent and independent self were - .04, - .03, .14 respectively.

Agentic and communal self-stereotyping and identity fusion. I conducted a second moderation analysis based on 10,000 bootstrap samples to test hypothesis 2. I included communal self-stereotyping as the predictor, identity fusion as the dependent variable, and agentic self-stereotyping as the moderator of the relation between communal traits and identity fusion. The overall R2 for the model was 0.16 (F(3,792) = 50.36, p < .001). Hypothesis 2 was supported, and the interaction effect between agency and communion on identity fusion was statistically significant (beta coefficient: 0.16, SE = 0.03, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval entirely more than 0: 0.10-0.22). The moderation analyses revealed that the relationship between communion and identity fusion was stronger at a high level of agentic self-description (beta coefficient: 0.41, SE = 0.08, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval higher than 0: 0.25-0.57) than at the average level (beta coefficient: 0.26, SE = 0.07, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval: 0.13-0.39) and a low level (beta coefficient: 0.11, SE = 0.06, p = .09, bias-corrected confidence interval including 0: -0.02 to 0.23; see Figure 6).

Figure 6 Moderator effect between agentic and communal self-description in study 4. Low and high results are based on -1 standard deviation and +1 standard deviation from the mean, respectively; identity fusion in the context of football fans.

Regression analyses show that collinerality, as measured by VIF, for agency was 6.20, and for communality = 5.77. Partial correlations between identity fusion and agency, communion, and interaction between agency and communion were - .04, - .12, .19 respectively.

Identity fusion and desire for self- and collective verification. To test hypothesis 3, which assumed a statistically significant interaction effect of desire to verify self-concept on identity fusion at the personal and group levels, I conducted a third moderation analysis based on 10,000 bootstrap samples using the Process macro, model 1 (Hayes, 2013). I included the desire for collective-level verification as the predictor, identity fusion as the independent variable, and self-verification as the moderator of this relation. The overall R2 for the model was 0.29 (F(3,792) = 109.20, p < .001). Hypothesis 3 was supported, and a statistically significant interaction effect between self- and collective verification for identity fusion emerged (beta coefficient: 0.08, SE = 0.02, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval entirely above 0: 0.05-0.11). Similarly to the previous analyses, the moderation analysis revealed that the relationship between identity fusion and the desire for collective verification was stronger at high level of self-verification (beta coefficient: 0.64, SE = 0.05, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval of more than 0: 0.56-0.73) than at an average level (beta coefficient: 0.52, SE = 0.04, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval: 0.45-0.59) and a low level (1 SD less than the mean; beta coefficient: 0.40, SE = 0.04, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval: 0.33-0.48; see Figure 7).

Figure 7 Moderator effect between desire for self- and group verification in study 4. Low and high results are based on -1 standard deviation and +1 standard deviation from the mean, respectively; identity fusion in the context of football fans.

Regression analyses show that collinerality, as measured by VIF, for self-verification was 4.68, and for collective self-verification was 5.95. Partial correlations between identity fusion and agency, communion, and interaction between agency and communion were - .18, - .11, .18 respectively.

Alternative models of moderation. In study 3 alternative models were also examined in order to check if identity fusion might be a significant moderator of the relationship between (1) agentic and communal self-stereotyping, (2) collective and self-verification, and (3) interdependent and independent self-construals. In (1) and (3) moderation models interaction between fusion and predictor variable did not reach significance, and strength of the relationship between predictors and independent variables was similar among low, average and highly fused individuals. For verification motives, interaction effect fusion x collective verification was low but significant with beta coefficient: 0.05, SE = 0.02, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval entirely above zero: 0.02-0.08). Moderation analyses revealed that the positive relationship between the collective verification and self verification motives was the strongest among highly fused individuals (beta coefficient: 0.65, SE = 0.04, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval entirely above zero: 0.57-0.72), average for medium fusion (beta coefficient: 0.57, SE = 0.03, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval entirely above zero: 0.52-0.63), and the weakest for low fused individuals (with beta coefficient: 0.50, SE = 0.03, p < .001, bias-corrected confidence interval: 0.43-0.56).

Discussion. The results of study 4 showed that all three hypotheses were confirmed when measuring strong adherence to a group of football fans. People with the strongest fusion with their close social group described themselves as very communal and very agentic at the same time. A similar relation was observed with the desire for self-verification: The most strongly fused football fans exhibited a high desire to verify their self-concept on the group and personal levels of self-definition.

General discussion

Applying measures from different theoretical traditions has shown that people who describe themselves as highly fused with their gender, close important group of their choice, and other football fans exhibit strongly developed interdependent and independent self-construals, as well as describe themselves as highly agentic and communal. These studies add to the literature on identity fusion and strong communal relations with close others by pointing out that those who self-stereotype themselves as simultaneously interdependent and independent are especially willing to take action on behalf of the group (for an overview of previous studies on identity fusion, see Gómez & Vázquez, 2015). Thus, the assumption that fused individuals do not lose their personal sense of self while gaining a strong group identity seems to be confirmed.

In the present studies, exploration of the self-descriptions of people fused with their country resulted in a somewhat less straightforward picture of the relations. Here, the role of strong independent and interdependent self-construals is not as clear as when examining identity fusion with other groups. When country was used as the reference group in study 1, the interaction between independent and agentic and interdependent and communal self-construals was not statistically significantly related to identity fusion. One explanation for this finding is that one’s relation with one’s country might also depend on different conditions, such as political views and ideology (e.g., the link between authoritarianism and fusion with country; see Besta et al., 2015). Moreover, country was the most abstract entity I included as a reference group, and the other groups were relational. The nature of these reference groups could have influenced the results and should be addressed in future studies. Although the picture of fusion with all groups might not be clear, these studies showed that, at least when the group was important for self-description, higher fusion was associated with thinking about oneself in terms of interdependence with and independence from other.

Limitations and Future Directions for Research

The present studies were correlational; therefore, it is possible that fused people see themselves as independent and communal at the same time, because of a feeling of oneness with a group, or that these traits facilitate identity fusion development. Additionally, in the fourth study correlation between some of the variables were relatively high and heightened collinerality could affect obtained results (it is especially true for relation between self-construals and identity fusion). However, despite the lack of experimental design and confirmed casual relations, it was important that the group of highly fused people could be described using terms and variables not directly related to identification with the group or without asking about specific feelings toward in-group members. Future experimental studies could explore whether priming the interdependent self results in stronger fusion, especially among people who exhibit independent self-construal. Similarly, it could be tested whether priming the independent self causes heightened feelings of personal and group identity overlap, especially among those who present themselves as an interdependent self before priming.

Moreover, it should be noted that short self-construal scales used in presented studies show low internal consistency. Thus future studies aimed at replication of presented results should employed more reliable measures of self-construals.

In addition, the role of self-construals in predicting identity fusion could be less important when fusion is measured during crowd gatherings or when the reference group emerges spontaneously as a result of gathering. The studies in this article were based on data gathered online when group membership was not contextually activated to a high degree. Researchers have shown that, among crowds, participants’ feeling of oneness with a group could stem from situational factors related to collective actions, such as induced positive emotions, self-expansion, and heightened readiness to enact common values and goals (Becker & Tausch, 2015; Khan et al., 2015; Reicher & Haslam, 2013). Thus, for participants in crowds involved in direct action on behalf of the group, self-construals are not as good predictors of identity fusion as other factors related to the situation of being with others for a common purpose.

To conclude, the studies in this article add to previous explorations of the state of identity fusion and inclusion of the other in the self (Wright, Aron, & Tropp, 2002). The results confirmed that this step in examining the association among self-construals, agentic and communal self-stereotyping, and the desire to self-verify revealed important relations and supported previous assumptions about individuals strongly fused with a group. Agentic, personal independence and group-related, close communal interdependent relations with others were important for fused individuals, and this could be one reason they were willing to further develop their agency through acting on behalf of in-group members.