Introduction

Worry consists of repetitive thoughts that are experienced as unpleasant and that concern an uncertain future outcome that is considered undesirable (e.g., Berenbaum, 2010; Mennin, Heimberg, Turk, & Fresco, 2002). Worrying is one of the most evolved types of behavior because it allows individuals to anticipate future danger, planning, experiment with ideas before implementing them, and evaluate alternative options (Mathews, 1990). However, worry loses its adaptive functions when people engage in it chronically to the extent that it feels uncontrollable. When this occurs, worry is associated with deteriorated functioning and low quality of life (see review in Watkins, 2008). Indeed, excessive worry is considered as one of the main symptoms in several diagnostic categories such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), depression, eating disorders, and hypochondria (Olatunji, Wolitzky-Taylor, Sawchuk, & Ciesielski, 2010). Furthermore, worry is considered as a pervasive process involved in the onset and maintenance of emotional disorders (Ehring & Watkins, 2008; Harvey, Watkins, Mansell, & Shafran, 2004).

The measurement of worry has been typically conducted with self-report instruments such as the Worry Domains Questionnaire (WDQ; Tallis, Eysenck, & Mathews, 1992), the Student Worry Scale (SWS; Davey, Hampton, Farrell, & Davidson, 1992), and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990). While some of the instruments explore worry in relation to some domains (e.g., SWS and WDQ), the PSWQ was designed as a general self-report that measures the tendency to engage in worry and the difficulty to control it without focusing on the worry content (Meyer et al., 1990).

The PSWQ is broadly considered as the gold standard measure of GAD-related worry (e.g., Hanrahan, Field, Jones, & Davey, 2013). It consists of 16 items that are responded on a 5-point Likert-type scale (5 = very typical of me; 1 = not at all typical of me), with scores ranging from 16 to 80 points. Higher scores indicate higher worry degree. The internal consistency of the PSWQ is excellent, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .91 to .94 (Meyer et al., 1990). The factor structure of the PSWQ has been a source of debate because some studies have found the better fit of a two-factor structure (Meloni & Gana, 2001; Olatunji, Schottenbauer, Rodríguez, Glass, & Arnkoff, 2007), one related with the direct measurement of worry (11 items) and the other one corresponding to the absence of worry (5 reverse-scored items). However, the second factor can be considered a statistical artifact rather than a meaningful construct, and some authors have argued that the PSWQ is better represented by only one factor (Brown, 2003; Brown, Antony, & Barlow, 1992; Hazlett-Stevens, Ullman, & Craske, 2004; Korte, Allan, & Schmidt, 2016). Indeed, Olatunji et al. (2007) suggested that the five negatively worded items lack practical utility because they do not correlate adequately with other psychological variables. Therefore, the authors suggested using only the 11 positively worded items of the PSWQ.

Some studies have explored the factorial equivalence of the PSWQ across gender and clinical and nonclinical participants. Brown (2003) found factorial equivalence across male and female clinical participants. Nuevo, Mackintosh, Gatz, Montorio, and Wetherell (2007) analyzed measurement invariance of an abbreviated, 8-item version of the PSWQ in American and Spanish older adults. They found that factorial equivalence across countries could be assumed for women but not for men. Lastly, Păsărelu et al. (2017) found factorial equivalence across gender, age and clinical diagnosis using the version of the PSWQ for children (i.e., PSWQ-C). The PSWQ-C was the result of a grammar analysis and the items were reworded to be readable for children (Chorpita, Tracey, Brown, Collica, & Barlow, 1997). However, the measurement invariance of the PSWQ across gender and clinical and nonclinical adult participants remains largely unexplored. This is an important issue for a gold standard measure such as the PSWQ because, in the absence of evidence in this regard, it is not justified to compare the PSWQ scores across gender and clinical and nonclinical samples.

Several Spanish translations of the PSWQ have been conducted that have shown good psychometric properties (e.g., Nuevo, Montorio, & Ruiz, 2002; Rodríguez-Biglieri & Vetere, 2011; Sandín, Chorot, Valiente, & Lostao, 2009). However, a common concern has been raised regarding the negatively worded items because they are difficult to understand for Spanish speakers. Indeed, Sandín et al. (2009) have suggested the use of only the positively worded items (an abbreviated version of the PSWQ that was called PSWQ-11) in Spain because the instrument showed better psychometric properties than the complete PSWQ. This suggestion by Sandín et al. is in line with Olatunji et al. (2007) findings regarding the lack of practical utility of the negatively worded items. Sandín et al. found a Cronbach’s alpha of .92 for the PSWQ-11 in a nonclinical sample.

To our knowledge, the validity of the PSWQ has not been explored in Colombia, which makes it difficult to conduct studies on GAD-related worry in this country. Additionally, testing measures in culturally diverse samples enhances both our confidence in the measure and the cross-cultural relevance of the underlying theory being measured (Elosua, Mujika, Almeida, & Hermosilla, 2014). Due to the concern raised with regard to the comprehensibility of the negatively worded items of the PSWQ in Spanish, we selected the version by Sandín et al. (2009) to explore the validity of the PSWQ in Colombian samples. Additionally, a secondary aim of this study was to explore the measurement invariance of the PSWQ-11 across gender and clinical and nonclinical participants. The PSWQ-11 was administered to two samples: a nonclinical sample (n = 710) and a clinical sample (n = 335).

Method

Participants

Sample 1. The sample consisted of 710 participants (71.4% females) with age ranging between 18 and 89 years (M = 27.51, SD = 10.18). The relative educational level of the participants was: 44.8% primary studies (i.e., compulsory education) or mid-level study graduates (i.e., high school or vocational training), 34.9% were undergraduates or college graduates, and 20.3% were currently studying or had a postgraduate degree. They responded to an anonymous internet survey distributed through social media. All of them were Colombian. Only 7.4% of participants in this sample were receiving psychological/psychiatric treatment. Also, 3.7% of participants reported consumption of some psychotropic medication.

Sample 2. It consisted of 335 patients (74% of them were women), with an age range of 18 to 63 years (M = 27.40, SD = 9.93). All participants were being evaluated in the institutional psychological consultation center, in which inexpensive psychological therapy is offered to general population in Bogotá. Most of the participants stated that the reason for consultation was suffering from emotional symptoms (91%), whereas the remaining participants consulted for family problems or social skills deficits. Only 7.2% of the participants reported that they were consuming some psychotropic medication.

Instruments

Penn State Worry Questionnaire - 11 (PSWQ-11; Meyer et al., 1990; Spanish version by Sandín et al., 2009). The PSWQ was designed to evaluate the permanent and unspecific degree of worry that characterizes GAD. The Spanish version of the PSWQ showed excellent psychometric properties although the authors recommended eliminating the negatively worded items because they were difficult to understand for Spanish speakers (Sandín et al., 2009). This recommended version was named PSWQ-11.

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales - 21 (DASS-21; Antony, Bieling, Cox, Enns, & Swinson, 1998; Spanish version by Daza, Novy, Stanley, & Averill, 2002). The DASS-21 is a 21-item, 4-point Likert-type scale (3 = applied to me very much, or most of the time; 0 = did not apply to me at all) consisting of sentences describing negative emotional states. It contains three subscales (Depression, Anxiety, and Stress) and has shown good internal consistency and convergent and discriminant validity. The DASS-21 has shown good psychometric properties in Colombia (Ruiz, García-Martín, Suárez-Falcón, & Odriozola-González, 2017). Strong positive correlations were expected between the PSWQ-11 and the DASS-21 subscales.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder - 7 (GAD-7; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Löwe, 2006). The GAD-7 is a 7-item, 4-point Likert-type scale (3 = nearly every day; 0 = not at all), self-report instrument that was designed as a diagnostic and severity measure of GAD. We used the Spanish translation of the GAD-7 for Colombia distributed by Pfizer. The GAD-7 showed good psychometric properties with α = .90 in Sample 1 and α = .87 in Sample 2. Strong positive correlations were expected between the PSWQ-11 and the GAD-7.

Ruminative Responses Scale - Short Form (RRS-SF; Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003; Spanish version by Hervás, 2008). The RRS-SF is a 10-item, 4-point Likert scale (4 = almost always; 1 = almost never) self-report instrument that was designed to measure the tendency to ruminate in response to feelings of sadness and depression. It contains two subscales called Brooding and Reflection. According to Treynor et al., brooding is the most maladaptive form of rumination, whereas reflection could have both maladaptive and adaptive aspects. The psychometric properties of the RRS-SF in Colombia are adequate (Ruiz, Suárez-Falcón, et al., 2017). Strong and medium positive correlations were expected between the PSWQ-11 and the Brooding and Reflection subscales, respectively.

Procedure

Participants in Sample 1 responded to an anonymous internet survey distributed through social media (e.g., institutional web-pages, Facebook profiles, etc.). The survey was called “Survey of Emotional Health in Colombia” and was responded on the platform www.typeform.com. After finishing data collection, a general inform was sent to the participants who provided an email address for that purpose. Afterwards, personal scores and options for receiving inexpensive psychological treatment were provided when requested by the person. Participants in Sample 2 responded to the questionnaires during one of the clinical assessment interviews at the beginning of treatment in the presence of their therapist. All participants provided informed consent and were given a questionnaire packet.

All participants in Sample 1 responded to the PSWQ-11 and DASS-21. One part of Sample 1 also responded to the RRS-SF (N = 370), whereas the other part responded to the GAD-7 (N = 340). With regard to Sample 2, all participants responded to the PSWQ-11, 242 responded to the DASS-21 and RRS-SF, and 94 to the GAD-7.

Upon completion of the study, participants were debriefed about the aims of the study and thanked for their participation. No incentives were provided for participation.

Statistical and Psychometric Analysis

Prior to conducting factor analysis, data from all samples were examined searching for missing values that were imputed using the matching response pattern of LISREL© (version 8.71, Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1999), which was the software used to conduct the confirmatory factor analyses (CFA). In this imputation method, the value to be substituted for the missing value of a single case is obtained from another case (or cases) having a similar response pattern over the remaining items of the PSWQ-11. Only two values were missing.

Because the PSWQ uses a Likert-type scale measured on an ordinal scale, a robust diagonally weighted least squares (Robust DWLS) estimation method using polychoric correlations was used to conduct the CFA. The WLS method is recommended in large samples with fewer than 20 items (Holgado-Tello, Chacón-Moscoso, Barbero-García, & Vila-Abad, 2010; Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996) as in the current study. In order to use the matrix of polychoric correlations, the assumption of bivariate normal distribution was analyzed by means of the chi-squared test and the percentage of tests that rejected the null hypothesis of bivariate normality for each pair of correlations. Due to the sensitivity of the chi-square test, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was also analyzed for each pair of correlations. Hooper, Coughlan, and Mullen (2008) point out that the parameter estimation is not very affected when RMSEA values are not higher than 0.1.

We computed the Satorra-Bentler chi-square test and the following goodness-of-fit indexes for the one-factor model: (a) RMSEA; (b) the comparative fit index (CFI); and (c) the non-normed fit index (NNFI). According to Kelloway (1998), RMSEA values of .10 represent an acceptable fit although for Hu and Bentler (1999) RMSEA values to consider acceptable fit should be .08. With respect to the CFI and NNFI, values above .90 indicate well-fitting models, and above .95 represent a very good fit to the data.

Additional CFA were performed to test for metric and scalar invariance across gender and clinical and nonclinical participants following Jöreskog (2005) and Millsap and Yun-Tein (2004). In other words, we analyzed whether the item factor loadings and item intercepts were invariant across samples and between men and women. In so doing, the relative fits of three increasingly restrictive models were compared: the multiple-group baseline model, the metric invariance model, and the scalar invariance model. The multiple-group baseline model allowed the eleven unstandardized factor loadings to vary across the samples and across gender. The metric invariance model, which was nested within the multiple-group baseline model, placed equality constraints (i.e., invariance) on those loadings across groups. Lastly, the scalar invariance model, which was nested within the metric invariance model, was tested by constraining the factor loadings and the item intercepts to be the same across groups. Equality constraints were not placed on estimates of the factor variances because these are known to vary across groups even when the indicators are measuring the same construct in a similar manner (Kline, 2005). For the model comparison, the RMSEA, CFI, and NNFI indices between nested models were compared. The more constrained model was selected (i.e., second model versus first model, and third model versus second model) if the following criteria suggested by Cheung and Rensvold (2002) and Chen (2007) were met: (a) the difference in RMSEA (ΔRMSEA) was lower than .01; (b) the differences in CFI (ΔCFI) and NNFI (ΔNNFI) were equal to or greater than -.01.

Coefficients alpha and McDonald’s omega were computed providing percentile bootstrap 95% confidence intervals (CI) to explore the internal consistency of the PSWQ-11 in Samples 1 and 2 and the overall sample (Viladrich, Angulo-Brunet, & Doval, 2017). In order to calculate these coefficients, the MBESS package in R was used (Kelley & Lai, 2012; Kelley & Pornprasertmanit, 2016). The remaining statistical analyses were performed on SPSS 20©. Corrected item-total correlations were obtained to identify items that should be removed because of low discrimination item index (i.e., values below .20). Descriptive data were also calculated, and gender differences in PSWQ-11 scores were explored by computing independent sample t-test. To examine criterion validity, scores on the PSWQ-11 were compared between participants in Sample 1 (nonclinical participants) and participants in Sample 2 (clinical participants). Pearson correlations between the PSWQ-11 and other scales were calculated to assess validity evidence based on relationships with other variables.

Results

Descriptive data and psychometric quality of the items

Table 1 shows the descriptive data and corrected item-total correlations for Samples 1 and 2. All items showed good discrimination, with corrected item-total correlations ranging from .67 to .88 in Sample 1, and from .65 to .85 in Sample 2.

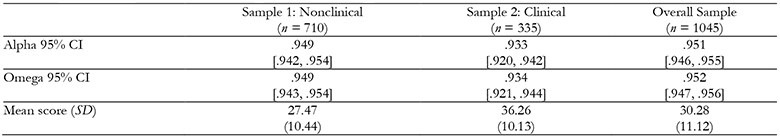

Table 2 shows that the alpha and omega coefficients of the PSWQ-11 were almost identical and excellent in all cases.

Validity evidence based on internal structure

Dimensionality

The results of the chi-square test to explore bivariate normality showed that this assumption was accepted in 22 % of the correlations. However, the RMSEA values were lower than 0.1 in all correlations, which supports the use of the matrix of polychoric correlations to conduct the CFA.

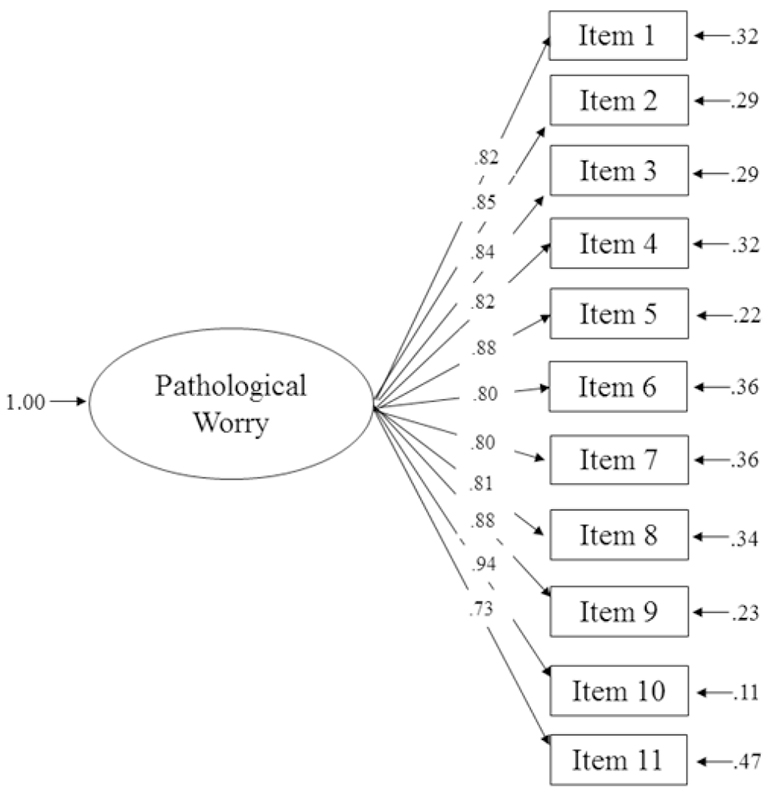

The goodness-of-fit values of the one-factor model were: S-Bχ 2 (44) = 430.73, p < .01; CFI = .99; NNFI = .98; and RMSEA = .092, 90% CI (.084, .099). The CFI and NNFI values indicated a very good fir to the data, and the RMSEA showed an acceptable fit according to the guidelines provided by Kelloway (1998), but poorer according to Hu and Bentler (1999). Overall, the fit of the one-factor model seemed to be acceptable. Figure 1 depicts the results of the standardized solution of the one-factor model.

Measurement invariance

Table 3 shows the results of the metric and scalar invariance analyses. Parameter invariance was supported at both the metric and scalar levels across gender and clinical and nonclinical participants because changes in RMSEA, CFI, and NNFI were lower than .01.

Validity evidence based on relationships with other variables

The PSWQ-11 showed correlations with all the other assessed constructs in theoretically coherent ways (see Table 4). Specifically, the PSWQ-11 showed strong positive correlations with emotional symptoms as measured by the DASS-21, symptoms of GAD, and brooding. Lower positive correlations were found with reflection.

Table 4: Pearson Correlations between the PSWQ-11 Scores and Other Relevant Self-report Measures.

Note. DASS-21 = Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale - 21; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder - 7; PSWQ-11 = Penn State Worry Questionnaire - 11; RRS-SF = Ruminative REsponse Style - Short Form; S = Sample; 1 = Nonclinical sample; 2 = Clinical sample; *p<.001

Means and standard deviations of the PSWQ-11 scores for nonclinical and clinical samples can be seen in Table 2. Participants’ mean score in the clinical sample (Sample 2) was higher than that of the nonclinical participants (Sample 1) (t = -12.80, p < .001). There were no statistically significant differences across gender in the PSWQ-11 in any of the samples.

Discussion

Although unconstructive worry is pervasive among emotional disorders (Watkins, 2008), GAD represents the prototype disorder in which worry plays a central role. Individuals suffering from GAD experience unspecific and permanent worry that is usually felt as uncontrollable. To assess this type of worry, Meyer et al. (1990) designed the PSWQ-11, which soon became the gold standard measure of GAD-related worry (Hanrahan et al., 2013).

Several Spanish versions of the PSWQ exist that have shown excellent psychometric properties although significant concerns have been raised with regard to the practical utility and comprehensibility of the negatively worded items (e.g., Olatunji et al., 2007; Sandín et al., 2009). Accordingly, Sandín et al. (2009) recommended using the PSWQ-11 in Spain, which is the result of eliminating the five negatively worded items. This version showed very good psychometric properties and a one-factor structure. We selected this version to explore the validity of the PSWQ in Colombia.

The PSWQ-11 was administered to a nonclinical sample (N = 710) and a clinical sample (N = 335) showing an excellent internal consistency (overall alpha of .95). The one-factor model showed an acceptable fit to the data, and measurement invariance at both metric and scalar levels was obtained across samples and gender. This indicates that the PSWQ-11 is measuring the same construct across nonclinical and clinical samples, and across gender. The PSWQ-11 also showed validity evidence based on relationships with other variables in view of the strong correlations found with measures of GAD, depression, anxiety, stress, and rumination. Lastly, the PSWQ-11 scores discriminated between clinical and nonclinical samples.

One important finding of this study is the factorial equivalence across gender, and nonclinical and clinical participants. These proofs of measurement invariance are important because the studies that use the PSWQ usually compare scores from these types of samples. In the absence of data supporting the factorial equivalence of the PSWQ, the comparison of the scores across these samples is not justified. With regard to factorial equivalence across gender, the current study extends the findings by Brown (2003) who found measurement invariance across male and female clinical participants. However, the factorial equivalence across gender in nonclinical adult participants had not been analyzed. On the other hand, the analysis of factorial equivalence across nonclinical and clinical adult participants had not been explored. Overall, the findings of this study, in conjunction with those of Păsărelu et al. (2017) with the children version of the PSWQ, point to considering that the PSWQ is invariant across gender and clinical and nonclinical participants.

Some limitations of this study are worth mentioning. Firstly, no systematic information was obtained concerning the diagnosis in clinical participants. Secondly, some validity aspects of the PSWQ-11 have not been analyzed in the current study (e.g., divergent validity, sensitivity to treatment effects, etc.). However, there is already evidence that the PSWQ-11 was sensitive to the treatment effect of brief acceptance and commitment therapy protocols focused on reducing repetitive negative thinking (Ruiz, Riaño-Hernández, Suárez-Falcón, & Luciano, 2016; Ruiz et al., in press). Thirdly, the percentage of women was significantly higher than the percentage of men in the composition of the samples. Also, the nonclinical sample was higher than the clinical sample. However, the number of male and clinical participants (approximately 300 for each category) was enough to conduct the measurement invariance analyses. Lastly, due to time constraints, all participants could not respond to all the questionnaires so that we decided to administer some of them a part of the sample and the others to the remaining part.

In conclusion, the abbreviated Spanish version of the PSWQ (i.e., PSWQ-11) suggested by Sandín et al. (2009) can be used to measure GAD-related worry in Colombia. The factorial equivalence found across gender and clinical and nonclinical samples justified the comparison of scores between male and women and between clinical and nonclinical participants. Further studies are needed to confirm the measurement invariance data found in this study across in other contexts. Also, additional studies might explore the psychometric properties of this version of the PSWQ-11 in other Spanish speaking countries and test for measurement invariance across countries.