Introduction

Alcohol consumption in adolescents continues to be a great social concern according to data from the survey on Drug Use in Secondary School Students -Encuesta sobre Uso de Drogas en Estudiantes de Enseñanzas Secundarias 2014/2015- (Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality, 2016), which paid particular attention to alcohol as one of the most widely used substances. In the last ten years young people have started to engage in various alcohol-related leisure activities, such as the botellón (groups of young people drinking in the street or in parks or public spaces), which has led to a significant increase in alcohol consumption in younger adolescents (Cortés, Espejo, Martín, & Gómez, 2010; Gómez-Fraguela et al., 2008). Binge drinking is the consumption of many alcoholic drinks in a short period of time, or drinking with the aim of getting excessively drunk (Courtney & Polich, 2009).

Adolescence is characterized by the early experience of new sensations (Azpiazu, Esnaola, & Sarasa, 2015). Many studies have made the association between sensation-seeking and drug consumption (González-Iglesias, Gómez-Fraguela, Gras, & Planes, 2014). These relationships can be particularly evident in adolescence, a time when there are developmental changes (Rodríguez-Fernández, Ramos-Díaz, Madariaga, Arrivillaga, & Galende, 2016), more opportunities for consumption (Staff et al., 2010), and when social support is particularly important (Gázquez et al., 2015a; Hernández-Serrano, Espada, & Guillén-Riquelme, 2016; Ramos-Díaz, Rodríguez-Fernández, Fernández-Zabala, Revuelta, & Zuazagoitia, 2016; Molero, Pérez-Fuentes, Gázquez, & Barragán, 2017). The tendency towards sensation-seeking becomes more evident in early adolescence, and is related to increased substance consumption in middle-adolescence (Charles et al., 2016). Authors such as Marcotte et al. (2012) note that one of the consequences of the tendency towards sensation-seeking is engaging in risky behaviors, specifically making reference to binge drinking.

Another question which has been the focus of research is adolescents' expectations about alcohol consumption (Lang et al., 2012; Reich, Below, & Goldman, 2010). Much of what adolescents believe about the consequences of consuming substances such as tobacco and alcohol is incorrect (Suárez, Del Moral, Martínez, John, & Musitu, 2016), which is related to minimizing the associated risks. Adolescents with positive attitudes or expectations towards alcohol have a higher risk of starting and continuing this pattern of consumption (Gázquez et al., 2015b).

The objective of this study is to examine the explanatory value of sensation-seeking and expectations about the effects of alcohol on patterns of binge drinking and the intention of continuing that behaviour in the following year.

Sensation-seeking and expectations about alcohol consumption

González-Iglesias et al. (2014) confirmed the importance of sensation-seeking in the explanation of young people's alcohol consumption and the mediating role of alcohol's perceived consequences and associated risks.

In research such as that by Pilatti, Godoy and Brussino (2011) a strong association has been seen between expectations about alcohol and the amount of alcohol drunk along with the intention to consume. Scott-Sheldon, Terry, Carey, Garey, and Carey (2012) found positive results about reducing the frequency of binge drinking episodes in young people on examining the efficacy of interventions based on treating expectations around alcohol to prevent abuse. McBride, Barret, Moore, and Schonfeld (2014) highlighted associations between positive expectations around alcohol and excessive drinking in students who were under 18 years old. Recent research on this topic (Stamates, Lau-Barraco, & Linden-Carmichael, 2016) has provided data on the relationship between alcohol intoxication at a young age and alcohol, with the expectations in this case playing a mediating role.

Researchers seem to agree on the positive relationship between positive expectations and alcohol consumption. The results about negative expectations are less conclusive however (Camacho et al., 2013). We found studies which suggest the existence of a positive relationship with alcohol consumption (Pabst, Baumeister, & Kraus, 2010), others which reject its importance as a determining factor (Patrick, Wray-Lake, Finlay, & Maggs, 2010), and yet others which ascribe negative expectations a protective function against consumption (Corbin, Iwamoto, and Fromme, 2011).

There is recent data which suggested that expectations around alcohol have greater weight in adolescents and young people than adults when it comes to consuming larger amounts and more frequent episodes of drunkenness (Monk & Heim, 2016). For many adolescents their social surroundings inhibit recklessness, but for others they encourage risk taking and seeking excitement (Gázquez et al., 2016). These experiences occasionally include taking drugs, with all the associated negative consequences (Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2015). MacPherson, Magidson, Reynolds, Kahler, and Lejuez (2010) found the tendency for adolescents to take risks to be a significant predictor of alcohol consumption. Curran, Fuertes, Alfonso, and Hennessy (2010) observed a strong correlation between driving under the influence of alcohol and sensation-seeking factors in adolescents; specifically with thrill and adventure seeking, disinhibition, and boredom susceptibility. Recently, data has been gathered which supports the predictor role of sensation-seeking (in conjunction with impulsivity) and socially prescribed perfectionism, in aggressive adolescent behaviour (Carbajosa, Catalá-Miñana, Lila, Gracia, 2017; Estévez et al., 2018; García-Fernández, Vicent, Inglés, Gonzálvez, & Sanmartín, 2017; Martínez-Loredo, Fernández-Hermida, Torre-Luque, Fernández-Artamendi, 2018; Pérez-Fuentes, Molero, Carrión, Mercader, & Gázquez, 2016).

Despite that, currently there is little research which has examined the combined predictive value of factors related to sensation-seeking and expectations around alcohol consumption in secondary school students.

The present study

In this study we intend to provide new data about the relationship that exists between the two variables and their influence over the pattern of alcohol consumption, along with the subject's own predictions about whether they will continue with that pattern of consumption in the short-to-medium term (during the following year).

We have the following specific objectives: a) identify the variables related to starting and continuing binge drinking, and b) checking whether dimensions of sensation-seeking and expectations around alcohol are statistically significant predictor variables of excessive alcohol consumption, along with the intention to continue this pattern of consumption.

We propose the following hypotheses based on the previous empirical evidence: 1) both positive and negative expectations around alcohol function as predictor variables of excessive alcohol consumption and its continuation in the following year, and 2) the tendency towards sensation-seeking has a greater weight as a predictor variable in the excessive consumption of alcohol than in the intention of continuing the habit during the following year.

Method

Participants

A total of 315 adolescents in compulsory secondary education in various state schools in the city of Almería participated in this study. The participants were aged between 14 and 18 years old, with a mean age of 15.22 years (SD = .89). Boys made up 45.4% (n = 247) of the sample, with a mean age of 15.15 years (SD = .85). Girls made up 54.6% (n = 172) of the sample, with a mean age of 15.28 years (SD = .92). About half (50.2%, n = 158) were in the third year of compulsory secondary education (3rd ESO), and about half (49.8%, n = 157) were in the fourth year. Nearly four-fifths of the students (79.9%, n = 247) said that they had consumed alcohol at least once, the most commonly reported numbers were “between 2 and 5 times” (30% of cases) and “more than 10 times” (27.5% of cases). Of those who said that they had drunk alcohol, 37.7% stated that they still drank alcohol at the time of the study.

Instruments

We created a questionnaire ad hoc to collect sociodemographic participant data (including age, sex, school year). We also included items taken from the evaluation questionnaire in the Toward No Tobacco Use program (TNT; Sussman et al., 1995), which was developed to collect information about tobacco and alcohol consumption at various times. We selected two items from the Spanish translation of the TNT by Torregrosa, Inglés, Delgado, & Martínez-Monteagudo (2007): one item to evaluate how often the subject drank alcohol to excess (How many times have you got very drunk in the last 30 days?), and another item to assess the intention to continue their pattern of consumption in the short-to-medium term (How many times will you drink alcohol in the next 12 months?).

Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire-Adolescent, Brief (AEQ-AB; Stein et al., 2007), a brief version of the Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire-Adolescent (AEQ-A) from Brown, Christiansen, and Goldman (1987). We used the Spanish adaptation by fff et al. (Fff). This instrument records beliefs about the positive and negative effects of alcohol on social and emotional behaviour in adolescents. The original questionnaire is reduced to seven items in the AEQ-AB, which are grouped into two scales: AEQ-ABp (positive expectations about the effects of alcohol) and AEQ-ABn (negative expectations about the effects of alcohol). Cronbach's alpha for the first component (AEQ-ABp) is .65 and for the second (AEQ-ABn) it is .48. We calculated the Composite Reliability Index for the overall scale CR=.74, and for each of the subcomponents: AEQ-ABp CR=.66 & AEQ-ABn CR=.47.

Sensation-seeking Scale (Pérez & Torrubia, 1986). This scale, with its 40 yes/no items, evaluates the trait of seeking new and risky experiences. It is made up of four subscales: Thrill and Adventure Seeking (TAS), Experience Seeking (ES), Disinhibition (DIS), and Boredom Susceptibility (BS). The authors obtained reliability coefficients between .70 and .87 for the subscales and Cronbach's alpha was .87 for the overall questionnaire scale. We found an alpha coefficient for the overall scale α = .77, and for the subscales: TAS α = .75, ES α = .45, Dis α = .66, & BS α=.48. The corresponding Composite Reliability Index for the overall scale was CR = .86 and for the subscales: TAS CR = .77, ES CR =.46, Dis CR = .67, & BS CR = .50.

Procedure

Before data collection we requested the participation of the appropriate authorities in each selected school, informing them of the most significant aspects of the research, the objective, procedures, and how the data would be used. In addition we told the participants that the confidentiality of their data was guaranteed. The questionnaires were completed by participants in their classrooms, having previously arranged the day and time with each group's teacher.

Data analysis

Firstly, we confirmed the multivariate normality of the sample following the criteria laid down by Finney & DiStefano (2006) in which the maximum allowed values for asymmetry and kurtosis are 2 and 7 respectively. In order to identify the variables related to the consumption of alcohol (episodes of binge drinking in the previous month and the intention to continue the consumption pattern during the following year) we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient, as well as the corresponding descriptive statistics. In order to understand how the predictor variables (Expectations about the effects of alcohol; Sensation-seeking: Thrill and Adventure Seeking, Experience Seeking, Disinhibition, and Boredom Susceptibility) were related to each of the criterion variables we performed a stepwise multiple linear regression for each of the cases.

We used Cronbach's alpha (Cronbach, 1951) to measure the internal consistency of the tests, or the reliability of the scores (Tang, Cui, & Babenko, 2014), as it is one of the most widely used estimators from classic psychometry (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011). In instruments with more than one construct, such as in our study, this index is not considered sufficient, as it does not deal with the influences of one construct on another (Dunn, Baguley, & Brunsden, 2014). In addition, as Cortina (1993) indicated, the number of items in the questionnaire, the interrelation of the elements, and the dimensionality are characteristics which may affect the value of alpha. Therefore, in order to have an alternative measure of internal consistency for the instruments used, we calculated the Composite Reliability Index (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Raykov, 1997), which addresses the interrelations of the constructs.

Results

Factors of sensation seeking and expectations about the effects of alcohol consumption

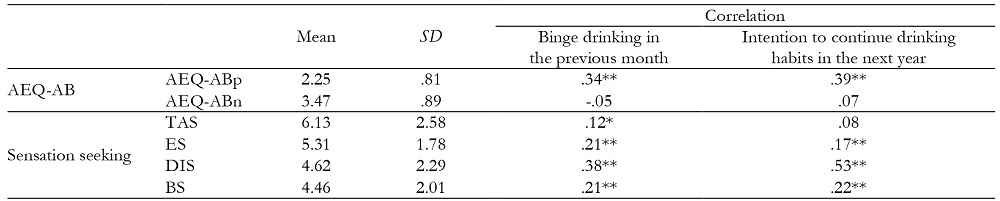

The correlation coefficients (Table 1) show that adolescents with high positive expectations about the effects of alcohol had more episodes of excessive drinking in the previous month (r = .34; p < .01), and exhibited a greater tendency towards maintaining their consumption in the following year (r = .39; p < .01). Negative expectations about the effects of alcohol, however, did not exhibit any relationships with the alcohol consumption variables we examined.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of expectations about the effects of alcohol and sensation seeking factors, and correlation coefficients with variables of alcohol consumption (N = 315).

Note: *Significant correlation at the level .05; **Significant correlation at the level of .01. AEQ-ABp = Positive expectations about the effects of alcohol; AEQ-ABn = Negative expectations about the effects of alcohol; TAS = Thrill and Adventure Seeking; ES = Experience Seeking; DIS = Disinhibition; BS = Boredom Susceptibiliy.

We saw positive correlations in all cases between the factors of sensation seeking and the incidence of binge drinking in the previous 30 days (TAS: r = .12; p < .05; ES: r = .21; p < .01; Dis: r = .38; p < .01; BS: r = .21; p < .01).

We found positive correlations for three of the sensation seeking factors with the prediction of alcohol consumption for the following year (ES: r = .17; p < .01; DIS: r = .53; p < .01; BS: r = .22; p < .01), the exception being Thrill and Adventure Seeking (TAS: r = .08; p = .12).

Predictor variables of binge drinking

According to the data in Table 2, the regression analysis delivered three models, model 3 having the best explanatory power with 19.6% (R2 = .19) of the variance explained by the factors included in the model.

Table 2. Stepwise Multiple Linear Regression Model (binge drinking).

Note: DIS = Disinhibition; AEQ-ABp = Positive expectations about the effects of alcohol; ES = Experience seeking.

In order to confirm the model's validity, we analysed the independence of the residuals. The Durbin-Watson D statistic gave a value of D = 1.97, confirming the absence of positive or negative autocorrelation. The value of t is associated with a probability of error less than .05 in all of the variables in the model. The standardized coefficients show that the variables with greatest explanatory power were: Disinhibition, Experience Seeking, and positive expectations about the effects of alcohol. The scores put Disinhibition as the strongest predictor of binge drinking.

Finally, the absence of collinearity between the variables in the model was assumed, due to the high values in the tolerance indicators and low values of the variance inflation factor (VIF).

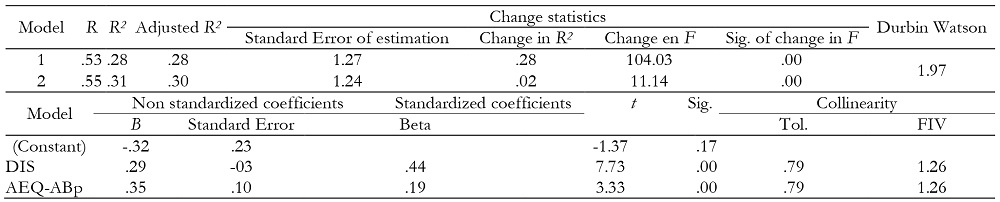

Predictor variables for the intention to continue habits of alcohol consumption

Table 3 shows the two models produced as a result of the regression analysis, where the second model had a percentage of explained variance of 31.2% (R2 = .31). Durbin-Watson's D statistic confirmed the validity of the model (D = 1.97).

Table 3. Stepwise Linear Regression Model (intention to continue consuming alcohol).

Note: DIS = Disinhibition; AEQ-ABp = Positive expectations about the effects of alcohol.

In relation to the t statistic, we found an association to a probability of error of less than .05 for all of the variables in the model: Disinhibition and Positive expectations bout the effects of alcohol. According to the values from the standardized coefficients, Disinhibition was the strongest predictor of the subjects scores about continuing to drink alcohol in the following year. Absence of collinearity between the variables was assumed on finding high values for tolerance indicators and low values for VIF

Discussion and conclusions

Firstly, the results from the correlation analysis show how variables of alcohol consumption are related to positive expectations about the effects of alcohol and sensation-seeking dimensions (Charles et al., 2016; González-Iglesias et al., 2014). This is the case for both a pattern of binge drinking and the intention to continue consuming alcohol in the short-to-medium term. We did not find any relationship with negative expectations about the effects of alcohol, which is in line with results from Patrick et al. (2010) and previous research indicating the inconclusive role of negative expectations about alcohol consumption in adolescents (Camacho et al., 2013). In that regard we did not find a clear association between the combination of positive and negative expectations in tandem with clear effects on alcohol consumption and the intention to continue drinking (Pilatti et al., 2011), however we did see an association with positive expectations when adolescents come to take decisions about drinking alcohol (McBride et al., 2014).

From these initial results we can already reject our first hypotheses: both positive and negative expectations around alcohol function as predictor variables of excessive alcohol consumption and its continuation in the following year. In this case the predictive value of positive expectations is present in both regression models, the model aiming to explain binge drinking as well as the model for the intention to continue consuming alcohol (Monk & Heim, 2016; Stamates et al., 2016). In neither of these cases was the role of negative expectations a determining factor (Camacho et al., 2013; Patrick et al., 2010).

We found that the tendency towards sensation seeking, so characteristic of adolescence (Azpiazu et al., 2015), was a predictor of alcohol consumption in adolescents, especially the Disinhibition dimension and, particularly when it comes to binge drinking, Experience Seeking. It is the presence of these two dimensions in the explanatory model of binge drinking that leads us to accept our other hypothesis: the tendency towards sensation-seeking has a greater weight as a predictor variable in the excessive consumption of alcohol than in the intention of continuing the habit during the following year.

Based on these results, we can say that the tendency towards sensation seeking plays a determinant role in adolescents' involvement in risky behaviors (MacPherson et al., 2010; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2015), while erroneous beliefs (positive expectations) about the results of drinking (Suárez et al., 2016) make it seem less risky and make it easier to begin and/or continue drinking habits (Gázquez et al., 2015b; González-Iglesias et al., 2014).

It is essential, therefore, to expand the research into the combined analysis of various factors related to alcohol consumption in adolescents and other associated risky behaviors (Gázquez et al., 2016; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2016) that may have consequences for their development and psychosocial adjustment (Gázquez e al., 2015a; Rodríguez-Fernández et al., 2016).

For future research, and bearing in mind the limitations in this study, it would be useful to increase the sample size and to include other psychosocial variables which have an influence on the adolescent decision making process, such as the role of the family and the influence of authority figures or peer pressure. Another limitation of this study suggests the need to approach the topic of expectations about alcohol consumption through an extended version of the instrument in order to compare and identify possible psychometric characteristics that might affect the results.

In this vein, following the analysis of internal consistency, and the moderate values achieved by some of the scales, further research might respond to the low number of reactives, lack of interrelation between elements or heterogeneous constructions (Cortina, 1993). Being aware of the limitations they produce and being cautious in interpreting or generalizing the results.

In terms of practical applications of the data, we would highlight its contribution as a base from which to design intervention programs for the prevention of alcohol consumption at young ages, and as the basis for counseling or advice for families or teachers to address alcohol consumption in the adolescent population.