Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer in women in all European countries and the first cause of death in women (Ferlay et al., 2013). Chemotherapy is a form of treatment widely used to treat breast cancer and prevent cancer growth and dissemination. It is composed of a mixture of different chemicals in different concentrations depending on the type and stage of the cancer being treated; with side effects diverging accordingly, ranging from changes in humor, hair weakening or loss and diminished resistance to infections and inflammation, to pain, nausea and vomiting (Breast Cancer Treatment Option Overview, 2018; Ogden, 2004). During the active treatment phase, it is important to consider the quality of life (QoL) since chemotherapy and other treatments, such as radiation and breast cancer surgery, are responsible for several side effects that have a strong impact on women’s wellbeing and body image (Browall et al., 2008; Collins et al., 2010). Literature shows that patients under treatment for breast cancer not only report worse physical function and QoL than the general population (Penttinen et al., 2010), but also lower physical and global QoL, when compared to recently diagnosed patients or survivors (Silva, Bettencourt, Moreira, & Canavarro, 2011).

Optimism can be conceptualized through two theoretical perspectives: dispositional optimism and explanatory style. Dispositional optimism is a personality trait that describes a relatively stable general disposition to expect positive outcomes in different situations (Carver, Scheier, & Segerstrom, 2010; Scheier & Carver, 1985). The explanatory style (Seligman, 1992), in turn, comprises the assumption that expectations regarding the future result from the interpretation of the causes of past negative events. Thus, individuals with an optimistic explanatory style would interpret the negative events as having a specific context, temporary, and external (no guilt feelings) causes.

Studies are controversial regarding the stability of optimism as a personality trait. It has been suggested that optimism remains relatively stable over time, mainly if there were no significant life transitions (Carver et al., 2010). A study conducted with women with breast cancer found that the levels of dispositional optimism did not change regardless of the reception of bad news, which lead the authors to conclude that optimism was a personality trait that remains stable not only over time but also regardless of the situation (Schou, Ekeberg, Sandvik, Hjermstad, & Ruland, 2005). On the other hand, other authors suggested that optimism might change over short periods of time and, therefore, has a state and not a trait property (Shifren, 1996; Shifren & Hooker, 1995).

Optimism has been extensively researched in recent years, and has consistently been shown to influence patients’ QoL, in chronic illnesss (Stanton, Revenson, & Tennen, 2007; Vilhena et al., 2014). Optimism has also been linked to better mental and physical health, in a variety of cancer locations (Allison, Guichard, & Gilain, 2000; Zenger, Brix, Borowski, Stolzenburg, & Hinz, 2009), including breast cancer (Colby & Shifren, 2013; Scheier & Carver, 1992; Schou et al., 2005), as well as a predictor of health outcomes, long-term QoL, and physical well-being (Carver et al., 2005; Carver, Smith, Petronis, & Antoni, 2006; Petersen et al., 2008; Rasmussen, Scheier, & Greenhouse, 2009). The recognized positive impact of optimism on health and its association with decreased psychological distress is important in order to understand the role of optimism on patient’s QoL (Carver et al., 2005; Carver et al., 2006; Colby & Shifren, 2013).

Family stress has also been related to cancer adjustment. A cancer diagnosis is a very stressful event that affects both the patient and the family. Family functioning patterns, in particular, have been found to influence patients’ distress during and after treatment (Edwards & Clarke, 2004; Kissane et al., 1996), due to the changes in family roles required to cope with cancer, as well as on patients’ mental and physical QoL (Northouse et al., 2002). However, studies regarding the role of family stress in breast cancer women during treatment (Moreira, Fernandes, Gomes, Silva, & Santos, 2013) are scarce and, from a heuristic point of view, it is important to understand how family stress may impact patients at risk of poor adjustment, with direct impact on QoL. Therefore, in the present study, the moderating role of family stress was analyzed.

Women with breast cancer often report body image issues related to treatment side effects (Collins et al., 2010; Fobair et al., 2006). Chemotherapy induced alopecia is described as a troublesome event that impacts body image causing distress, which may negatively impact QoL (Lemieux, Maunsell, & Provencher, 2008). Several studies have revealed that problems with body image were related to lower QoL and more psychological distress (Al-Ghazal, Fallowfield, & Blamey, 1999; Avis, Crawford, & Manuel, 2005; Helms, O’Hea, & Corso, 2008).

Psychological distress is common among cancer patients, during the active treatment phase, with a reported prevalence of 37.5% for moderate depression and 15.6% for moderate or severe anxiety, during chemotherapy (Reece, Chan, Herbert, Gralow, & Fann, 2013). Adjuvant treatments are associated with increased anxiety and depression (Browall et al., 2008) that in turn have been related to several QoL dimensions due to dysphoria, stress, less interpersonal relationships, and impaired performance (Penttinen et al., 2010; Reich, Lesur, & Perdrizet-Chevallier, 2007; So et al., 2010). In fact, anxiety and depression have been shown to be independently related to QoL in breast cancer patients, especially regarding the emotional, physical and functional dimensions (Ho, So, Leung, Lai, & Chan, 2013).

Given the multiplicity of dimensions related to QoL assessment, this study focused on QoL dimensions of emotional and physical functioning. Emotional (or psychological) QoL is conceptualized as the individuals’ perception of affective and cognitive wellbeing, while physical QoL refers to the perception of one’s physical condition that has been shown to significantly predict survival (Braun, Gupta, Grutsch, & Staren, 2011; Gupta, Granick, Grutsch, & Lis, 2006; Seidl & Zannon, 2004).

Models of psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and disability (Livneh & Antonak, 2005; Northouse, Kershaw, Mood, & Schafenacker, 2005) emphasize the process and strategies involved in adapting/overcoming the impact of chronic disease, such as cancer, on QoL. Based on these theoretical frameworks, dispositional optimism, body image and family stress were analyzed, in this study, as psychological attributes that may influence adaptation to chronic illness, with an impact on psychosocial outcomes, such as QoL. Therefore, the aims of this study were: 1) to analyze the relationship between psychological variables such as distress, family stress, body image, dispositional optimism and QoL; and 2) to find the clinical and psychological variables that contributed to physical and emotional QoL; 3) to analyze whether family stress moderated the relationship between patients’ psychological distress and QoL, during breast cancer treatment.

Methods

Participants

This study used a cross-sectional design. One hundred women participated in the study. The inclusion criteria were: a) age over 18 years old; b) diagnosis of breast cancer; and c) undergoing chemotherapy treatment at the moment of the evaluation. Information on demographic and clinical variables was collected through medical records, including duration of diagnosis and cancer recurrence. From the initial sample, 5% refused to participate in the study due to time constraints but they did not differ on sociodemographic and clinical variables from participants.

Instruments

EORTC QLQ-C30 (Aaronson et al., 1993; Portuguese version of Pais-Ribeiro, Pinto, & Santos, 2008). The QLQ-C30 assesses 9 cancer related QoL dimensions using 24 items grouped into functional (physical, role, cognitive, emotional and social), global health/QoL and symptom subscales (fatigue, pain, and nausea/vomiting). The other 6 items assess symptoms of dyspnea, appetite loss, sleep disturbance, constipation and diarrhea. Higher scores on functional and global health/QoL indicate a higher level of functioning and better QoL. Higher scores on symptom subscales indicate more severe symptoms. For the purpose of this study, only the physical (5 items) and emotional (4 items) subscales were included in the analysis with Cronbach’s alphas in this sample of .71 and .87 for each dimension, respectively.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scales - HADS (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983; Portuguese version of Pais-Ribeiro et al., 2007). This scale assesses global psychological distress with 14 items answered on a 4-point Likert scale (0-3), according to symptom frequency during the previous week. Separate scores can also be computed for anxiety and depression subscales, with 7 items evaluating depression and 7 items assessing anxiety. Higher scores indicate higher anxiety/depression or psychological distress. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .86 for the global scale.

Body Image Scale - BIS (Hopwood, Fletcher, Lee, & AlGhazal, 2001; Portuguese version by Moreira, Silva, Marques, & Canavarro, 2010). BIS is a 10 item self-report measure that evaluates the cancer patient’s body image using a 3-point Likert scale with scores ranging from 0 to 30. Higher scores indicate worst body image. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .94.

Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R) (Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994; Portuguese version by Laranjeira, 2008). The LOT-R is a 10-item measure, with 3 items that assess an optimistic view of the future, and 3 items reflecting negative expectations. The 4 remaining items act as distractions and are not used in the analysis (e.g.: “I enjoy my friends a lot”). The items are answered according to a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). For this study, optimism was considered a unidimensional construct and the scores were calculated using the optimistic and the reversed pessimistic items. Therefore, higher scores indicate higher dispositional optimism. In this sample Cronbach’s alpha was .72.

Index of Family Relations- IFR (Hudson, 1992; Portuguese version by Pereira & Roncon, 2010). The IFR is a 25-item measure of family stress that assesses the severity of problems in the family. The IFR produces a 0-100 score with higher scores indicating more severe problems. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was .89 for the IFR.

Procedure

Data was collected in an oncology unit of a central hospital in the North of Portugal using a consecutive sample of women undergoing chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer. Patients were approached by a research team member and invited to participate in the study, the day of the chemotherapy session. Participation was voluntary. The study was approved by the hospital’s Ethical Committee and all participants were knowledgeable of the purposes of the study and signed an informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Pearson correlation was used to analyze the association between continuous variables, and the point-biserial correlation was used regarding the dichotomous variables. Clinical variables significantly associated with QoL were introduced in the regression model to determine their association with physical and emotional QoL. For this purpose, two separate hierarchical regression models (method enter) were computed, with clinical variables introduced in step 1 and psychological variables in step 2. Duration of diagnosis was categorized in two groups: over six months (44%) and less than six months (56%). The moderation analysis was performed using the Baron and Kenny’s method (1986).

The statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 24 with the level of significance set at p < .05.

Results

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

The mean age of women was 52.45 (SD = 11.93). From the total sample, 45% completed primary school education, 27% reported having 9 years of education and 28% high school education or more. Most participants were married or in a long-term relationship (76%), 9% were single, 6% divorced, and 5% widowed.

Approximately half the women had been diagnosed for less than 6 months (56%) and 29% had recurrent breast cancer. Seventy-seven per cent of women had breast cancer surgery, either a mastectomy (63.5%) or breast conserving surgery (36.5%).

Relationship between Clinical and Psychological Variables and QoL

The results showed that duration of diagnosis (r = -.365, p <. 001) and cancer recurrence (r = -.394, p < .001) were negatively associated with physical QoL. However, there were no differences according to type of surgery (mastectomy vs breast conserving) on body image (t(71) = .967, p = .337), physical QoL (t(71) = -1.919, p = .059), and emotional QoL (t(72) = -.499, p = .620).

Physical QoL was negatively associated with psychological distress (r = -.412, p < .001) and body image (r = -.392, p < .001). Emotional QoL was negatively associated with psychological distress (r = -.676, p < .001), body image (r = -.397, p < .001), and family stress (r = -.339, p = .001). Therefore, women with lower physical QoL levels reported more psychological symptoms and worst body image, and women with lower emotional QoL also showed more family stress.

Dispositional optimism was positively related to physical (r = .205, p = .042) and emotional (r = .293, p = .003) QoL. Women with more psychological distress also reported worst body image (r = .597, p < .001) and more family stress (r = .387, p < .001) (Table 1).

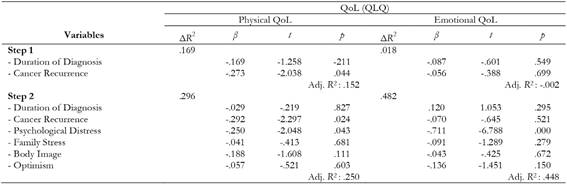

Contribution of Clinical and Psychological Variables to Physical and Emotional QoL

Physical QoL was associated with cancer recurrence and psychological distress, and the model explained 30% of the variance. Women with recurrent breast cancer and higher psychological distress reported lower physical QoL. Psychological distress was the only variable associated with emotional QoL, with the model explaining 48% of the variance (Table 2).

Moderation Analysis

Since there were no differences on family stress according to the presence/absence of a partner (U = 768.00, p = .78), the moderation analysis was performed for the entire sample. Results showed that family stress was a significant moderator in the relationship between psychological distress and emotional QoL but not in the relationship between psychological distress and physical QoL. When family stress was high (t = -5.57, p < .001), there was a negative relationship between psychological distress and emotional QoL (r = -6.76, p < .001). Therefore, family stress seems to have a higher impact on emotional rather than physical QoL (Figure 1).

Discussion and Conclusion

This study aimed to analyze the relationship between clinical and psychological variables in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment; to determine the predictors of physical and emotional QoL; and to analyze the role of family stress as a moderator in the relationship between psychological distress and QoL. Results showed that lower QoL was related to less dispositional optimism, more psychological distress and dissatisfaction with body image. Higher psychological distress was associated with lower physical and emotional QoL and cancer recurrence was also associated with physical QoL. The relationship between psychological distress and emotional QoL was moderated by family stress.

The significant relationship between psychological distress, body image and QoL reinforces the importance of body image, showing that women with worse body image, in this study, also reported lower QoL and more psychological disturbances (Avis et al., 2005; Helms et al., 2008; Rosenberg et al., 2012). These results are probably due to physical changes related to cancer treatments that may create a discrepancy from the ideal-self, causing distress or adjustment disorders (White, 2000; White & Hood, 2011).

The influence of psychological factors on QoL has been consistently reported in several studies that showed a general consensus in cancer research concerning the negative influence of psychological distress on both physical and emotional QoL. In fact, feelings of stress and fear add to the emotional burden of cancer (Holzner et al., 2001; Penttinen et al., 2010; So et al., 2010), and depression symptoms increase the perception of pain, side effects severity, and are associated with physical symptom intensity (Badger, Braden, Mishel, & Longman, 2004; Reich et al., 2007), making depressed patients more likely to report impaired QoL (Ardebil, Bouzari, Shenas, Zeinalzadeh, & Barat, 2011). In a study by Rabin, Heldt, Hirakata, and Fleck (2008), depressive symptoms predicted all QoL dimensions and the initial psychological distress was the most important predictor of long term QoL, underlying the importance of evaluating patients’ psychological symptoms, especially considering the association of QoL with psychological distress and overall survival (Montazeri, 2008).

The results concerning dispositional optimism are in line with the studies showing an association between optimism, QoL and emotional well-being. In women with breast cancer, studies have found that higher optimism and lower pessimism were related to better health-related QoL (Petersen et al., 2008), less depression and anxiety, as well as lower psychological distress (Applebaum et al., 2013; Leung, Atherton, Kyle, Hubbard, & McLaughlin, 2015), and better social and mental functioning (Colby & Shifren, 2013). Considering the results of the contribution of dispositional optimism to QoL, the present study is in accordance with the results of Härtl et al. (2010) that reported no significant predictive value for optimism. One possible explanation may have to do with the confounding effect between optimism and psychological distress, with the latter being a more important variable on QoL when considered together (Härtl et al. (2010). Nonetheless, it is clear that further research is needed to clarify the relationship between optimism and QoL, in different stages of disease breast cancer.

Cancer recurrence was associated with physical QoL showing its importance as a major stressor that impacts the patients’ physical well-being, as has been shown by the literature (Northouse et al., 2005). These results highlight the need to better understand the psychological aspects of cancer recurrence, in order to promote better adjustment and decrease psychological strain, during chemotherapy treatment.

Moderation analysis showed a significant impact of high family stress on emotional QoL. Several studies have focused on the association between family functioning and psychological distress, reporting a direct relationship between family functioning and psychological distress (Kissane et al., 1996), highlighting the influence of problematic communication patterns, repressed feelings and less problem solving skills on patient’s distress (Edwards & Clarke, 2004). The impact of family stress on emotional QoL may be due to the role that family members have to play on managing emotions and shaping patients’ experience and feelings about cancer (Thomas, Morris, & Harman, 2002), which explains why family stress acted as a moderator. This result adds to the importance of a family-centered approach in cancer care (Edwards & Clarke, 2004), not only for patients but the family as well, during chemotherapy treatment.

Conclusion

Given the role that psychological distress and QoL have on cancer treatment response and overall survival, it is important to analyze which variables impact these relationships. The results showed the importance of psychological variables such as distress, body image, and family stress on QoL. With increased survival rates and life-expectancy, it becomes paramount to assess women on such variables in order to improve their wellbeing and decrease their negative impact on QoL.

The present study focused on the relationship between clinical and psychological variables in breast cancer showing the role of family stress in the relationship between psychological distress and QoL. According to the results, it is important to screen and intervene on family stress in patients with breast cancer. We believe that, in cases where the screening reveals high family stress, the intervention should be offered in a family context. The family is an essential context of disease management and source of support and family support from partners was found to be the most important support by breast cancer women, acting as a buffer against psychological distress (Hasson-Ohayon, Goldzweig, Braun, & Galinsky, 2010).

The main limitations of this study were the cross sectional design, the exclusive use of self-report measures, and the use of the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire to assess QoL, while the specific measure of EORTC QLQ-BR23 would have been more adequate in breast cancer. Also, the type of chemotherapy protocol was not taken into consideration. Future studies should follow breast cancer women using longitudinal designs in order to identify patterns of adaptation to cancer and QoL, during the different stages of treatment with different chemotherapy treatment protocols and assess the role of family stress on patients’ QoL, as the duration of diagnosis increases.