Introduction

The Internet is an ideal site for socialization and interaction by adolescents. It is a space where they can communicate and interact with their peers. Adolescence is a period of great change in terms of social, physical and personal environments, including the phase of sexual development. One example of how the new technologies and virtual spaces are promoting and driving new forms of sexual behaviour may be seen with the phenomenon of sexting (Lenhart, 2009), which consists of the exchange of sexually explicit or provocative content (text messages, photos and videos) using smartphones, the Internet or the social networks (Morelli, Bianchi, Baiocco, Pezzutti & Chirumbolo, 2016). There are many inconsistencies when it comes to defining sexting, with some authors limiting it to the sending of sexually explicit photos or videos while others also include the sending of sexually provocative text messages (Mitchel, Finkelhor, Jones & Wolak, 2012). Furthermore, differentiation has been made between active sexting (the sending of sexually explicit images, videos or text messages) and passive sexting (the receipt of sexually explicit images, videos or text messages) (Temple & Choi, 2014). And some studies (e.g. Walker, Sanci & Temple-Smith, 2011) have distinguished between consensual sexting (the voluntary sending of sexual content) and non-consensual sexting (when an image is incorrectly used and sent without permission), considering this latter to be a form of sexual violence.

In a systematic review of the practice of sexting by adolescents, the prevalence of this behaviour has been estimated at between 7% and 27% in adolescents aged 12 to 18 (Cooper, Quayle, Jonsson & Svedin, 2016). Similarly, in a recent meta-analysis (Madigan, Ly, Rash, Ouytsel & Temple, 2018) it was concluded that the mean prevalence of active sexting, as found in 39 studies, was 14.8% for adolescents with a mean age of 15.16 years. Variations in the estimated prevalence of sexting in youth may be a result of the heterogeneous definitions that are used, as well as the distinct instruments used to assess this behaviour. However, consensus exists in the prior research regarding the belief that sexting behaviour increases with age (Cooper et al., 2016). So, in a sample of Spanish adolescents, it has been found that 36.1% engage in sexting at the age of 17 (Gámez-Guadix, de Santisteban & Resett, 2017), whereas in university samples, the percentages apparently increase, reaching figures as high as 75.7% for the sending of sexually provocative text messages (Delevi & Weisskirch, 2013).

Sexting and personality

Scientific literature has attempted to determine the factors that may determine this sexting behaviour (Hudson & Fetro, 2015; Vanden Abeele, Campbell, Eggermont & Roe, 2014), and personality has been studied, among other potential factors. Examining personality may assist in the understanding of why adolescents engage in risky behaviour. In fact, prior research has examined the relationship between personality and risky sexual behaviour in adolescents (Hoyle, Fejfar & Miller, 2000).

The big five model (Goldberg, 1990) has proven quite useful in many different fields of behaviour (Barlett & Anderson, 2012; Vedel, 2014), and the broad personality traits proposed by this model (neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness) have also been considered to be correlates of sexting in some prior studies. It has been found that high levels of neuroticism and extraversion and low levels of conscientiousness are associated with increased sexting (Butt y Philips, 2008; Gámez-Guadix, et al., 2017). Regarding agreeableness, a negative relationship with sexting has been found (Delevi & Weisskirch, 2013; Gámez-Guadix, et al., 2017). No significant relationships between openness and sexting have been seen. Using longitudinal data, (Gámez-Guadix & De Santisteban (2018) have shown that low conscientiousness and high extraversion in T1 are associated with increased sexting at the one-year follow-up.

Despite this interest in the big five, prior studies have not examined the Five-Factor Model (FFM; McCrae y Costa, 1996) with regards to sexting. This model not only considers the general domains of personality, but it also looks at specific facets, permitting a more thorough analysis of the traits making up each of the general factors. Although past studies have examined more specific personality variables, they have done so in a non-systematic and poorly integrated way. So, sexting has been found to be related to difficulties in emotional competencies, emotional awareness and emotional self-efficacy (Houck et al., 2014), as well as a low capacity for self-control (Kerstens & Stol, 2014), impulsiveness (Baumgartner, Weeda, Van der Heijden & Huizinga, 2014), anxiety (Drouin & Landgraff, 2012) and depression (Temple et al., 2014). Therefore, an ordered and detailed analysis of the relationship between the more specific aspects of personality and sexting is necessary. The FFM offers an ideal framework to organize the results of personality within this area of study.

Sexting and psychosocial consequences

Although researchers have taken an interest in those variables that are potential predictors of sexting, much less is known about its potential consequences. Studies have tended to consider the social and legal consequences of sexting, but they have failed to look at the psychosocial consequences of this behaviour. It has been suggested that the underestimation of the risks associated with sexting may place adolescents in situations of psychosocial vulnerability (Fajardo, Gordillo & Regalado, 2013). Currently, studies are being undertaken to examine the relationship between sexting and the bullying and cyberbullying phenomena. For example, Kopecky (2011) found that 73% of the adolescents participating in his study reported the risk of potential intimidation upon engaging in sexting. And Reyns, Burek, Henson and Fisher (2013) found an increased probability of cybervictimization in adolescents engaging in sexting behaviour. Some researchers have considered the emotional well-being of adolescents who engage in sexting, with somewhat inconsistent findings. Thus, some studies have emphasized the relationship between sexting, depression, anxiety and suicide attempts (Jasso-Medrano, López-Rosales & Gámez-Guadix, 2018; Van Ouytsel, Van Gool, Ponnet & Walrave, 2014). But other researchers have failed to find any associations with psychological well-being (Hudson, 2011). Beyond the limited results from prior studies, it may be hypothesized that the images and videos used in sexting can be subsequently used for extortion purposes, potentially increasing the degree of cybervictimization and further decreasing the emotional well-being of the adolescents.

A major limitation of the prior research, both in terms of potential determinants and consequences, is that, with very few exceptions (Gámez-Guadix & De Santisteban, 2018), the studies have been conducted using a cross sectional approach. There is the clear need for longitudinal studies on this topic in order to organize the variables involved in sexting according to time and to propose theoretical models on the causes and consequences of this phenomenon (e.g. Galovan, Drouin & McDaniel, 2018).

Our study

This study attempts to fill this void in the research on this area, by examining how personality may predict changes in sexting in adolescents after one year. Unlike other studies, it includes a wide range of personality facets; and, it examines some of the potential consequences of sexting.

The specific objectives of this study are: 1) to analyze the relationship between personality features of the FFM (domains and facets) and sexting behaviour assessed one year later and 2) to determine if the big five factors permit longitudinal prediction of changes occurring in sexting behaviour in a one-year period. Furthermore, we propose the examination of the potential consequences of sexting, both in terms of externalizing and internalizing dimensions of adolescent behaviour, specifically, aggression-victimization behaviour (both in-person and online) and emotional well-being. Given the inconsistencies in defining sexting, we should note that in this study, we consider active and consensual (voluntary) sexting behaviour, which includes the sending of sexually explicit photos, videos and text messages. Furthermore, since some past studies have suggested that sexting behaviour is more common in males than in females, and since the functions of sexting may differ for males and females (Delevi & Weisskirch, 2013), the potential moderating effect of gender on the predictors and consequences of sexting shall be considered.

Given the lack of previous longitudinal studies, the hypotheses are quite tentative. According to past cross sectional research, it is expected that high levels of neuroticism and extraversion, as well as low levels of agreeableness and conscientiousness will be associated with sexting (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2017). When considering the specific facets of the FFM, it is expected that anxiety, depression, impulsivity, excitement seeking and especially, the specific facets of the conscientiousness dimension (i.e. self-discipline or dutifulness) will be related with sexting behaviour (Baumgartner et al., 2014; Temple et al., 2014). As for the psychosocial consequences of sexting, once again, the lack of past longitudinal studies prevents a well-established hypothesis. However, it is expected that adolescents who engage in sexting will have a greater probability of victimization and cybervictimization, given that some results from cross- sectional studies suggest the potential risk of cybervictimization in adolescents engaging in sexting behaviour, as the sexual images sent to others might be used against them (Jasso-Medrano et al., 2018). Furthermore, sexting may decrease the emotional well-being of adolescents, as suggested by prior cross sectional studies reporting that higher levels of anxiety and depression are associated with sexting behaviour (Drouin & Landgraff, 2012; Temple et al., 2014).

Methodology

Participants

This work is part of a broader longitudinal study that was initiated in 2015 (T1) with the assessment of an incidental sample of 910 adolescents attending eight Galician (Spain) schools. Of these, 624 participants were assessed one year later (T2), and they form the definitive study sample. The participants were enrolled in various course years of secondary education, attending public schools in urban and semi-urban areas. Of the overall sample, 55% of the adolescents were female; the mean age of the participants is 14.35, with a standard deviation of 1.55 (age range from 12 to 19).

As for the lost participant data between T1 and T2, a retention rate of 69% was achieved. The loss of 31% of the participants was due to 1) the impossibility of following one of the academic groups due to data collection difficulties caused by class scheduling; 2) the absence of participants during the second data collection period, due to absenteeism on the data collection date, change of school or repetition of academic year. When comparing the adolescents who continued in the study with those who did not, it was found that those who continued in the study had a lower mean age (F = 38.28, 1/905 gl, p < .001), were more likely to be female (Chi-square: 5.88, 1 gl, p < .01) and were more likely to have never engaged in sexting behaviour (Chi-square = 4.81, 1 gl, p < .05).

Instruments

Measurements in T1

FFM domains and facets. In order to assess the personality traits, an abridged version of the NEO PI-R for youth was used (JS NEO-S; Ortet et al., 2010), consisting of 150 items that are responded to with a Likert-type scale of 5 points ranging from completely disagree to completely agree. The JS NEO S was developed as an adaptation of the NEO PI-R for young people (Ortet et al., 2012), and both the abridged and the full version have been previously demonstrated to have suitable psychometric properties. The usefulness of these questionnaires for the assessment of the 5 dimensions and 30 facets of the FFM has been supported by the results of distinct studies (e.g., Ortet et al., 2010; Alonso & Romero, 2017). In this study, the alpha coefficients for the domains range between .81 (Openness) and .90 (Conscientiousness). The alpha coefficients of the distinct facets range between .46 (O3-Feelings) and .78 (N3-Depression). The alpha coefficients of 24 of the 30 facets are equal or greater than .60. Those facets having coefficients of less than .60 were O3-Feelings (.46), N5-Impulsiviness (.49), A4-Compliance (.50), N1-Anxiety (.52), N2-Hostility (.53), C3-Dutifulness (.56), C1-Competence (.57), E5-Excitement-seeking (.58) and E1-Warmth (.59). These low values in some of the scales are to be expected, given the reduced number of items, and these results are similar to those of prior studies (; Ortet et al., 2010).

Measurements in T1 and T2

Sexting. To assess sexting, we have used the Frequency of Sexting questionnaire (Weisskirch & Delevi, 2011) (See Appendix). It contains 5 Likert-type items having five response options, with a score of between 0 (Never) and 4 (Frequently). These items refer to the sending of sexual photos or videos of oneself, in lingerie or naked, the sending of sexually provocative text messages (WhatsApp, SMS, etc.) or those suggesting the intent to engage in some sort of sexual relation (e.g. “How often have you sent a nude photo or video of yourself using your cell phone?”). In our study, a reliability of .84 was found in T1 and of .84 in T2.

Bullying/cyberbullying. To assess bullying behaviour, the Spanish version of the European Bullying Intervention Project Questionnaire (EBIPQ) (Ortega-Ruiz, Ortega y Casas, 2016) was used. It contains 14 items which, in this study, were used with a response scale of Never-0 times (0), A few times-Between 1 and 2 times (1), Sometimes-Between 3 and 5 times (2), Several times-Between 6 and 10 times (3) and Often-More than 10 times (4), and with a reference period of the last six months. The questionnaire contains two dimensions: victimization and aggression, with an alpha coefficient of .90 and .91 in T1 respectively and with alpha coefficients of .84 and .82 in T2 respectively. For both dimensions, the items refer to actions such as hitting, insulting, threatening, robbing, using offensive language, excluding or spreading rumours (e.g., “Someone has insulted me”, “I have threatened someone”).

To assess cyberbullying behaviour, the Spanish version of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire (ECIPQ) (Del Rey et al., 2015) was used. The cyberbullying scale contains 22 items that, in this study, were used with a response scale of Never-0 times (0), A few times-Between 1 and 2 times (1), Sometimes-Between 3 and 5 times (2), Several times-Between 6 and 10 times (3) and Often-More than 10 times (4), and with a reference period of the last six months. The questionnaire contains two dimensions: cybervictimization and cyberaggression, with alpha coefficients of .87 and .85 respectively in T1 and with alpha coefficients of .85 and .86 respectively in T2. For both dimensions, the items refer to actions such as using offensive language, excluding or spreading rumours, supplanting one’s identity, etc., all via electronic means (e.g., “Someone has posted personal information about me over the Internet”, “I have excluded or ignored someone in a social network or chat”).

Emotional well-being. To assess emotional well-being, the most well known indicators for the operationalization of this concept were used: the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson, Clark & Tellegen, 1988) which includes 20 items, 10 of which refer to the Positive Affect subscale (e.g. “Excited”, “Proud”) and 10 to the Negative Affect subscale (e.g. “Irritable”, “Fearful”), measured over the period of the last year. This instrument was previously used in Spain with adolescents, and both reliability and validity were supported (Romero, Luengo, Gómez-Fraguela & Sobral, 2002). In our study, alpha coefficients in T1 of .87 were found for Positive Affect and .88 for Negative Affect and alpha coefficients in T2 of .85 for Positive Affect and .88 for Negative Affect.

Procedure

Fourteen schools were contacted, of which eight agreed to participate in the study. Questionnaires were completed in the school classrooms between October of 2015 and February of 2016 in T1 and between October of 2016 and February of 2017 in T2, under the supervision of a research team member and after receiving the parental consent and the consent of the adolescents. Fifteen percent of the adolescents did not return the consent form and were therefore unable to participate in the study. Students were ensured that the collected data would remain anonymous and confidential. A self-generated key (created by the students) was used to pair the questionnaires corresponding to the same individual in T1 and T2, without the need for the adolescent’s name to appear on the questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

In order to highlight the study objectives, an analysis of correlations was conducted, determining the association between the personality variables (domains and facets) measured in T1 and the sexting measured in T1 and T2. Subsequently, a cross-sectional regression analysis was performed to analyze how the big five personality traits explain sexting behaviour in T1. In order to determine how personality predicts changes in sexting in the one-year period, a hierarchical regression analysis was carried out using sexting in T2 as a criteria and controlling for the stability of this variable (auto-regressive effects; Selig & Little, 2012). As for the potential consequences of sexting, correlation analyses were carried out between sexting and the potential consequences measured in both time periods. In addition, the schema that is typically used in studies that examine the prediction of change between two moments in time (Newsom, 2015) was used to examine the potential consequences of sexting during the follow-up period: it analysed how T1 sexting may predict potential consequences (bullying/cyberbullying and emotional well-being), upon controlling for the prior levels of the same.

Results

Prior to the central analyses of the study, a descriptive analysis was carried out on the sexting data from our sample. Regarding the prevalence data, it was seen that 39.9% of the adolescents making up our sample engaged in at least some sexting during the first year of the study. During the year of follow-up, 44.4% of the adolescents engaged in at least some sexting behaviour. On the other hand, the results indicate that significant differences exist between males and females in T1 sexting behaviour; in the male subsample, more participants engage in sexting than in the female subsample (45% of the males as compared to 35% of the females; Chi-square: 7.95, 1 gl, p < .01). In T2, it is also seen that, within the male subsample, there is a greater number of participants engaging in sexting as compared to the female subsample (49% of the males versus 40% of the females; Chi-square: 4.12, 1 gl, p < .05).

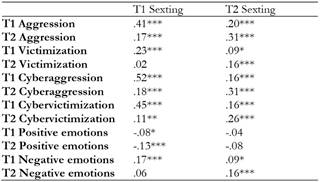

In response to objective 1 of this study, to analyse the relationship between the FFM personality traits (domains and facets) and the sexting behaviour assessed one year later, an analysis of correlations was carried out between the personality variables measured in T1 and the sexting behaviour registered in T2. The results (also including the cross sectional correlations between personality and sexting in T1) are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Zero-order correlations between personality variables (domains and facets) measured in T1 and sexting measured in T1 and in T2.

As for the cross sectional relationships, the sexting behaviour in T1 relates with lower scores on openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness, taking into account the big five personality traits. When considering the specific facets of the FFM, the most intense correlations (significance p < .001) are found in hostility (positive relationship), values (negative relationship) and all of the specific facets of the agreeableness and conscientiousness dimensions (negative relationship).

As for the relationships that are the specific subject of this study (personality T1-sexting in T2), sexting in T2 is found to be related with higher scores on depression, impulsiveness and vulnerability, within the neuroticism domain. It is also related with higher scores in the general domain of extraversion. However, taking into account the facets of this domain, the only significant and positive relationship is found for the excitement seeking facet. When considering the agreeableness domain, a significant (and negative) relationship is found to exist between sexting and overall agreeableness. Similarly, sexting is related with lower scores in straightforwardness, altruism and compliance. Sexting is significantly and negatively related with the conscientiousness domain and with the distinct facets that make it up. Our results do not reveal significant relationships between the domain and the facets of openness with sexting behaviour.

It should be noted that, although significant, some of the correlations are of a low intensity; this is the case for the facets of depression and vulnerability and the general dimension of extraversion, which have correlations of lower than .10.

Furthermore, a cross-sectional regression was performed in order to analyse how the five personality domains explain variance in sexting in T1, upon controlling for the effects of age and gender (0 = male; 1 = female). The results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Regression analysis for the prediction of T1 sexting based on the big five personality domains.

The results indicate that high extraversion and low agreeableness and conscientiousness significantly predict sexting in T1; the variance explained by the personality variables was .07.

To examine the change produced in sexting behaviour between T1 and T2, the means were compared using t tests for related groups. The results indicate that significant differences exist in sexting behaviour between T1 and T2 (t = -2.65, 601 gl, p < .01; Cohen’s d = .03). The mean scores indicate that the sexting behaviour tends to increase between T1 (mean = 6.68) and T2 (mean = 7.08).

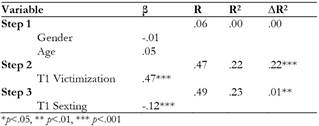

In response to objective 2 (to determine if the big five permit longitudinal prediction of the evolution of sexting behaviour over a one year period), a hierarchical regression analysis was performed, using the sexting behaviour in T2 as the criteria variable. The age and gender variables were introduced in the first step of the equation. In the second step, T1 sexting was introduced. And finally, in the third step, the personality variables were introduced, specifically, the five general personality domains. In this way, while controlling for age and gender, and for the stability of sexting, it was possible to examine whether the personality variables contribute to predicting a change in sexting between T1 and T2. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Regression analysis for the prediction of the change in sexting between T1 and T2 based on the big five personality domains.

Results of the hierarchical regression analysis reveal that, in the first step, gender and age contribute significantly to the prediction of T2 sexting; in the second step, T1 sexting also predicts T2 sexting, with a significant and positive beta, indicating a significant level of stability between T1 and T2. In the third step, upon partialling out this stability, extraversion emerges as a significant predictor of sexting. The positive beta sign indicates that a high degree of extraversion predicts increases in sexting behaviour at the one year follow-up point. The increase in explained variance (.02) is small, but statistically significant.

To verify whether the predictive effects may vary based on gender, the regression analysis was repeated, including the multiplicative interactions gender x personality traits (neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness and responsibility). None of the interactions were significant.

With regards to the potential consequences of sexting, first, the correlations between T1 and T2 sexting and the criteria included in this study (aggression- victimization, cyberaggression-cybervictimization and positive and negative emotions) were examined, also measuring them at both moments. The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4: Zero-order correlations between sexting measured in T1 and in T2 and potential consequences measured in T1 and T2.

The results indicate that T1 and T2 sexting are significantly related with all of the criteria assessed in both moments in time, with a few exceptions (i.e. the relationship between T1 sexting and victimization and negative emotions in T2; the relationship between T2 sexting and positive emotions in T1 and T2).

To examine the change taking place in the criteria between T1 and T2, the means were compared using t tests for related groups. The results indicate that significant differences exist between T1 and T2 for in-person victimization (t = 2.61, 595 gl, p < .01; Cohen’s d = .20) and cybervictimization (t = 3.26, 599 gl, p < .001; Cohen’s d = .25); specifically, the mean scores indicate that victimization and cybervictimization in T1 (6.49 and 3.37, respectively) are higher than in T2 (5.85 and 2.59, respectively). As for in-person aggression, the mean scores indicate that aggression in T1 is higher (4.26) than in T2 (3.62), with a t = 3.16, 596 gl, p < .001; Cohen’s d = .25. However, the results indicate that cyberaggression does not significantly change, as an average, between T1 and T2 (t = 1.59, 596 gl, p > .05). As for emotional well being, the change between T1 and T2 is significant, both for positive emotions (t = -5.73, 574 gl, p < .001; Cohen’s d = .35) as well as for negative ones (t = -4.62, 576 gl, p < .001; Cohen’s d = .18); taking into account the mean scores, the positive and negative emotions in T1 were higher (33.56 and 23.76, respectively) than in T2 (35.51 and 25.32, respectively).

To determine if sexting predicts the changes occurring in these variables, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted using the potential consequences in T2 as the criteria variables. Once again, gender and age variables were introduced in the first step. In the second step, the potential consequences assessed in T1 were introduced, to control for the stability of these variables. And finally, T1 sexting was introduced in a third step. These analyses allowed us to determine if T1 sexting is associated with changes in the potential consequences during the T1-T2 period.

In all of the examined variables, significant stability effects were obtained from T1 to T2. In the third step of the equations, no significant predictive effects from sexting were obtained for the potential consequences in the variables of aggression, cybervictimization, cyberaggression and negative emotions. However, significant predictive effects were obtained for the variables of victimization and positive emotions. The results corresponding to these two criteria are presented in Tables 5 and 6.

Table 5: Regression analysis for the prediction of the change in victimization between T1 and T2 based on T1 sexting.

Table 5 reveals that, in the first step of the equation, the sociodemographic variables (age and gender) do not contribute significantly to the prediction of the victimization measured in T2. In the second step, T1 victimization appears as a predictor of T2 victimization and in the third step of the equation, after partialling out the prior levels of victimization, it may be observed that T1 sexting significantly contributed to the regression model, with a negative coefficient in its prediction of victimization in T2, indicating that a high score in T1 sexting predicts a decrease in the victimization experienced between T1 and T2.

Table 6: Regression analysis for the prediction of the change in positive emotions between T1 and T2 based on T1 sexting.

As for the positive emotions, Table 6 reveals that age significantly contributes in all of the steps of the model and positive emotions in T1 have a close relationship with the positive emotions assessed one year later. But furthermore, the table reveals that the inclusion of T1 sexting in the third step of the equation may result in a significant increase in the explained variance: controlling for the stability of the criteria variable, sexting has a significant and negative coefficient in its prediction of positive emotions in T2, so, having a high score in sexting in T1 predicts decreases in the positive emotions experienced between T1 and T2.

The increase in variance explained by T1 sexting is quite small (.01), both in victimization as well as in the positive emotions, however, it is statistically significant.

All of the regression analyses were repeated, including the multiplier term gender x T1 sexting. No significant interactions were detected between gender and sexting in any of the studied criteria: the effect of sexting on the studied variables does not appear to vary based on gender.

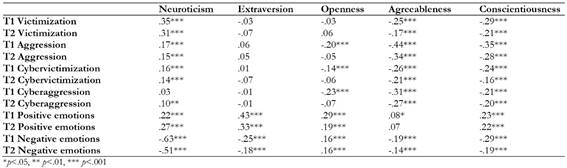

Furthermore, the role of personality on the prediction of the potential consequences of sexting was also analysed. First, the correlations between the big five personality factors1 and the psychosocial criteria considered in this study were calculated. The results are presented in Table 7.

Table 7: Zero-order correlations between the big five personality domains and potential consequences of sexting.

The analyses of correlation, as shown in the table, revealed the existence of significant correlations between the big five personality factors and the psychosocial criteria; the highest correlations (greater than .44) were established between neuroticism and T1 negative emotions and agreeableness and T1 aggression.

Given the relationships that have been verified between the big five personality traits and the potential consequences of sexting, the regression analyses were repeated, including the five personality domains, in an intermediate (third) step of the equation. The results did not reveal substantial variations. The effect of sexting on victimization and on positive emotions remains significant, even when controlling for the effect of personality. Sexting behaviour has a significant and negative coefficient in its prediction of victimization (-12, p < .01) and on positive emotions (-.10, p < .05).

Discussion

This study was focused on sexting behaviour in a sample of adolescents, in an attempt to examine both its personality precursors and its potential psychosocial consequences.

As for the first study objective (to analyse the relationship between the FFM personality features -domains and facets- and the sexting behaviour that was assessed one year later), the results obtained on the general personality domains are congruent with previous cross sectional studies (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2017); that is, adolescents engaging in more sexting behaviour were found to have higher scores on extraversion and lower scores on agreeableness and conscientiousness when measured one year earlier; no significant relationship was found for the openness domain. As for neuroticism, the relationship with the general domain is not significant; however, significant relationships were found with some certain facets of this domain. So, adolescents engaging in sexting are more likely to score higher on depression, impulsiveness and vulnerability. Thus, it is possible that adolescents who are more emotionally vulnerable may use sexting as a way to gain the acceptance of their peers. Furthermore, the inability to control their impulses may contribute to the sending of messages, photos and videos, without considering the potential consequences. Similarly, past studies have revealed the implication of impulsivity on other risky behaviours (e.g. drug use) (De Wit, 2009). As for extraversion, the only significant facet is the excitement-seeking, which is the facet that is the most closely related to the need to seek sensations and emotions. Sexting may respond in part to this need for thrilling experiences, as it provides intense sensations, quickly and easily. In fact, past research has described how sensation seeking is associated with risky sexual behaviour (Charnigo et al., 2013); the association with sexting appears to display a similar pattern. As for agreeableness, it is found that young people engaging in sexting tend to have low previous scores on agreeableness. As suggested by Gámez-Guadix et al. (2017), sexting, like many interactions with the new technologies, often takes place in a decontextualized context, with adolescents who are less agreeable possibly finding the Internet to be a comfortable environment. In addition, past research supports a relationship between agreeableness and sexual behaviours; specifically, it has been suggested that low levels of agreeableness are related with increased risky behaviour (Hoyle et al., 2000). Finally, sexting has the most intense relationship with the domain of conscientiousness and with all of its corresponding facets. Based on the data obtained, it can be affirmed that adolescents engaging in sexting have less confidence in their skills, are less able to organize themselves, have a lower dutifulness, a lower achievement striving, lower levels of self-discipline and deliberation. Prior studies (McCrae, Costa & Busch, 1986) have established that individuals low in conscientiousness are less inhibited, more hedonistic and have a greater interest in sex; this would be in accordance with increased sexting behaviour, which definitively represents a new way of experimenting with sexuality.

Thus, this study reveals that adolescents who engage in sexting during the second year of the study had previously (one year earlier) scored higher on extraversion and lower on agreeableness and conscientiousness; they had also scored higher on some of the specific facets of neuroticism (depression, impulsiveness and vulnerability).

This study also attempts to determine whether or not the big five factors can predict changes taking place in sexting behaviour over a one year period. On the one hand, a relatively high stability has been found between T1 and T2 for sexting behaviour, with an adolescent who engages in sexting being likely to continue to do so at subsequent times. On the other hand, of the big five factors, extraversion is the only one that predicts changes in sexting at the one year follow-up. As is typical in this type of auto-regressive model (especially when the change between the two time periods is small), the effect size is not high (Adachi & Willoughby, 2015); however, the results reveal that extraverts have a greater probability of increasing their sexting behaviour over a one year period. These results are consistent with those found in the longitudinal study conducted by Gámez-Guadix and De Santisteban (2018). Our work highlights the importance of extraversion as a precursor of the progression produced in sexting behaviour throughout adolescence.

Furthermore, in this study, we examine the potential outcomes of sexting on aggression-victimization behaviour (both in-person and online) and emotional well-being. In this sense, it is found that, at the one year follow-up, sexting predicts a decrease in the traditional levels of victimization as well as a decrease in the level of positive emotions. As mentioned in the introduction, although past research has mentioned the potential psychological consequences of sexting, there is a lack of empirical studies, longitudinally based, aimed to analyze the potential consequences of sexting. Some studies (Reyns, Burek, Henson & Fisher, 2013) report a greater probability of cybervictimization in adolescents engaging in sexting and other studies (Gámez-Guadix, et al., 2017) suggest a potential vulnerability of adolescents to cybervictimization as a result of this sexting behaviour. However, our results in this prospective and predictive study indicate that sexting predicts decreases in victimization. One potential explanation for this result is based on the meaning that sexting has for adolescents. Thus, the search for popularity appears to be one of the forces that motivates young people to engage in this behaviour (Lippman & Campbell, 2012; Ringrose, Harvey, Gill & Livingstone, 2013). Prior studies have shown that the more popular adolescents tend to engage in more sexting and, in parallel, those seeking greater acceptance between members of the opposite sex also have a greater tendency to engage in sexting (Vanden Abeele et al., 2014). It is also known that, in adolescents, being more popular is related to lower levels of victimization (Buelga, Cava & Musitu, 2012). Therefore, popularity may mediate in the influence of sexting on victimization. In any case, it is necessary to replicate these results in other contexts and with distinct follow-up periods, in order to verify to what degree this finding is consistent, thereby reconceptualising the relationships of sexting with bullying.

On the other hand, our study also shows that sexting is associated with decreases in the level of emotional well-being of youth. Specifically, sexting is associated with subsequent reductions in the level of positive emotions of youth. It appears that sexting is an increasingly popular practice in youth and they engage in this behaviour impulsively, without considering the potential consequences. This may lead to social and personal difficulties that may be associated with a decrease in positive emotions over time. The effects found in the regression analysis are robust, given that they maintain the statistical significance even when controlling for the effect of personality. It should be noted that this is an initial exploration of the potential consequences of sexting from a longitudinal perspective; future studies should thoroughly analyse the emotional effects, in the short and long term, that are the result of sexting.

Therefore, in summary, this study, examining the antecedents and consequences from a longitudinal perspective, has found that, in a one year follow-up, extraversion is a predictor of increased sexting and, at the same time, sexting predicts a decrease, in the one year follow-up, of victimization and positive emotions.

This study has certain limitations that should be mentioned. First, it is clear that additional long-term studies are necessary, since they would permit a more thorough analysis of the dynamics of the predictors and the consequences of sexting. On the other hand, despite its longitudinal nature, the study does not establish a cause-effect relationship between the variables, although it does suggest predictive effects which are compatible with the potential influence of personality on sexting, and of sexting on victimization and positive emotions. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, there are also certain psychometric limitations of some of the facets of the JS NEO-S which have low internal consistencies, and this may have weakened some of the relationships found. However, even with the less consistent facets, the associations are coherent with previous expectations and/or with the relationships found in the other facets corresponding to the same factor. Furthermore, we should note that the study was conducted using only self-reporting measures; the use of more diverse measures may permit more robust conclusions which would strengthen the current body of research on sexting.

Despite these limitations, this study offers a complete and detailed image of the relationship between personality traits and sexting, since it includes the analysis of the facets of the general FFM domains. In addition, its longitudinal design permits additional knowledge on the prediction of sexting behaviour, while considering personality. This prospective study has also helped to examine some of the potential psychosocial consequences of sexting, which have not been previously analysed from a longitudinal perspective.

This study reveals that sexting is a set of frequent behaviours in youth, apparently influenced by basic personality trends and that may also have relevant consequences on health and well-being throughout adolescence. Sexting in young people is a phenomenon that, in terms of predictors, correlates and consequences, deserves systematic investigation. Further study of the psychological dimensions and processes involved in sexting may help to uncover strategies to promote the proper use of the new technologies by adolescents, thereby minimizing their negative consequences.

texto en

texto en