Introduction

Although each developmental period is important in itself, the adolescent years are especially important. In the transition to adolescence, there are multiple changes in emotional and cognitive abilities and peer, school, and parent-child relationships (Ben-Zur, 2003). Although the transition to adulthood is considered a stormy period, contemporary theorists state that this is exaggerated and that the turbulent passage of this period is not inevitable (Arnett, 1992). Many researchers emphasize that young people should focus on health matters and social, emotional and moral strengths rather than focusing solely on problematic, risky behaviors, and that these aspects need to be improved (Larson, 2000; Lerner, Almerigi, Theokas and Lerner, 2005). Similarly, Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000) state that psychology simply locates an individual within a model of disease model and is concerned with treating illnesses. According to them, this situation neglects the development of individuals and society. Positive psychology aims to improve positive features rather than removing problematic ones. Psychological well-being, subjective well-being and happiness are considered as components of a good life. However, these concepts seem to be used interchangeably on occasion (Park, 2004). To make a distinction, there are two general points of view: hedonic and eudaimonic. While the hedonic approach focuses exclusively on achieving happiness, the eudaimonic view focuses on understanding and self-realization. According to the precautionary approach, goodness is defined as seeking pleasure and escape from pain while, from the eudaimonic point of view it is defined as the fully functioning individual (Ryan and Deci, 2001). Subjective well-being corresponds to the hedonic tradition, whereas psychological well-being corresponds to the eudaimonic tradition (Keyes, Shmotkin and Ryff, 2002). Subjective well-being has various components such as both positive and negative emotions and satisfaction with life. The positive and negative emotional components indicate the frequency of positive and negative emotions in an individual's emotional life, while life satisfaction is a cognitive aspect of subjective well-being and it refers to how an individual evaluates his/her life in general. According to this, the positive emotions felt by an individual and a high level of satisfaction about his/her own life together with a low level of negative emotions indicate a high level of subjective well-being (Diener, 1984; Myers and Diener, 1995). In this approach, subjective well-being and happiness are used in the same sense.

According to the literature, demographic factors such as age, gender and class level are not important determinants of the happiness of adolescents. However, in regard to adolescents’ happiness, family appears to have an especially important place (Ash and Huebner, 2001; Dew and Huebner, 1994; Gilman and Huebner, 2003; Flouri and Buchanan, 2003; Joronen and Åstedt-Kurki, 2005). In the happiness and peace of mind of adolescents, peers as well as parents play an important role. Piko and Hamvai found that social support from parents and peers increases the life satisfaction of adolescents (Piko and Hamvai, 2010), while it decreases emotional problems (Helsen, Vollebergh and Meeus, 2000). The ability of the adolescent to connect well with parents and peers (Baytemir, 2016; Laghi, Pallini, Baumgartner and Baiocco, 2016) and the quality of his/her friendships was found to be an important predictor of the happiness of adolescents (Demir, Özdemir and Weitekamp, 2007; Raboteg-Saric and Sakic, 2014). Adolescents who have more close relationships with their friends have a higher level of interpersonal competence and those with higher interpersonal competence have fewer feelings of hostility, less anxiety and higher self esteem (Buhrmester, 1990). Interpersonal competence can be positively associated with a greater degree of balance and popularity while it is also negatively associated with depression and loneliness (Buhrmester, Furman, Wittenberg and Reis, 1988). This study took as its basis the concept of interpersonal competence expressed by Buhrmester et al. (1988) as a group of interpersonal skills. They stated that interpersonal competence consists of five tasks: initiating relationships, providing emotional support, showing strength, self-disclosure and conflict resolution. In many studies, a significant positive relationship between interpersonal competence and happiness was shown (Baytemir, 2016; Demir et al., 2012; Segrin and Taylor, 2007). According to Diener and Seligman (2004), social relationships are important for subjective well-being, and good social relationships are influential in the formation and maintenance of subjective well-being. According to Eryılmaz (2012), social support, being understood, and close and trusting relationships ensures that the adolescents improve their subjective well-being. Similarly, Park (2004) suggested that positive life events and the interaction of the adolescent with other individuals lead to the improvement of life satisfaction in adolescents.

Adolescents spend most of their time in school. School is a living space where students participate in teaching activities as well as where they spend time with their peers and teachers, interact with them and engage in various social activities. The perception of their school experiences seems to be related to the adaptation and happiness of the students. Schools are places, which develop students’ social and emotional competencies besides their academic competencies. Modern education systems emphasize the development of a student as a whole. In Turkey, high school students receive forty-hours of lectures in total, including compulsive and elective activities and drama. Most of the courses consist of compulsory courses (MNE, 2018). As students are subjected to a difficult exam at the end of the secondary education, they are expected to display an increasing academic performance in this process. This situation is not only relevant in Turkey as in all education system within formal classroom environments academic demands from the student increase with higher class levels (PISA 2015). It was revealed in PISA, 2015 Report that 15 years old-age group students are more stressful in terms of academic issues, have lower life satisfaction, lower sense of belonging to the school and have a weaker relationship with their teachers in terms of fair-treatment in comparison to other OECD country students. The environment that students learn is considered as important in terms of forming students’ development and life satisfaction (PISA, 2015).

It is emphasized that a sense of connection to a school promotes healthy development and the achievements of adolescents in school (Libbey, 2007). According to Anderson-Butcher, Amorose, Lachini and Ball (2012), the perceptions of adolescents about school experiences can be understood in terms of “school connectedness”, “academic monitoring” and “academic motivation”. These factors have an important place in the students' academic achievement and positive development. Libbey (2004) stated that school connectedness is defined by different concepts such as “school atttachment”, “school engagement” and “school bonding”. However, Libbey (2004) suggested that common factors such as the support and interest of the teacher, the presence of friends and participation in extracurricular activities are important, although different concepts are used in defining a students’ commitment to a school. One commonly used definition of school connectedness was made by Goodenow (1993). According to him it indicates: “The extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included, and supported by others in the school social environment.” Academic monitoring emphasizes how teachers, students and other staff in the school attain standards that represent success and meet expectations for academic success. Academic monitoring motivates students in their work, and their academic achievement. Students feel more responsible for their performance in reaching the desired goals if they are regularly monitored by their teachers (Lee, Smith, Perry and Smylie, 1999). Academic motivation, which is another component in the students’ perceptions of the school experience, is defined as their sense of responsibility to school and learning and the pleasure experienced through this (Murphy, Weil, Hallinger and Mitman, 1982). Motivation is often used to describe students' choice of activities, their responsibilities, their persistence, their search for support and their performance at school (Meece, Anderman and Anderman, 2006). Academic motivation seems to be important in explaining students’ success at school (Fortier, Vallerand and Guay, 1995).

School connectedness improves the overall health and happiness (Allen and Bowles, 2012). It was found that school connectedness is significantly related to students’ emotional health (Kidger, Araya, Donovan and Gunnell, 2012), academic achievement and compliance (Pittman and Richmond, 2007). The connection of students to the school is associated with high academic achievement and less unwanted behavior (Goodenow, 1993) reduced symptoms of depression (Joyce and Early, 2014; Schwerdtfeger Gallus, Shreffler, Merten and Cox, 2015; Yıldız and Kutlu, 2015), and less bullying and victimization (Cunningham, 2007; Duy and Yıldız, 2014). In a longitudinal study on adolescents (Stiglbauer, Gnambs, Gamsjäger and Batinic, 2013), found that positive school experiences affected happiness while shared happiness positively affected positive school experiences. According to Suldo et al. (2009), adolescents' happiness may be associated with various experiences at school and especially support from their teachers. They found that the perception of support from teachers is a significant source of the happiness of students. It was shown that academic self-efficacy and academic adjustment are significantly related to life satisfaction (Lent, do Céu Taveira, Sheu, Singley, 2009), while a perceived increase in the academic motivation of students causes a decrease in their anxiety and an increase in their competence (Gottfried, 1990). According to Aypay and Eryılmaz (2011), subjective well-being decreases when adolescents lose interest in school. Students' satisfaction with their experience of school increases their satisfaction with life (Akın, 2015). The students’ satisfaction with their experience of school, their sense of connection to school and their degree of academic motivation increases their happiness and reduces the negative aspects of their lives.

In the experience of school, the relationships of students with teachers and peers are closely related to their participation at school. To be accepted and loved by classmates, to have friends in school and similar social settings is a fundamental requirement for the social and emotional development of children and adolescents (Monjas, Martín-Antón, García-Bacete and Sanchiz, 2014). Adolescents who are more social and accepted by their peers are more committed to the school than those who are socially isolated and rejected by their peers (Eccles et al. 1993). Birch and Ladd (1997) emphasize the importance of the quality of the student-teacher relationship in developing positive attitudes to the school and feeling attached to the school, as well as to friends. A study by Uslu and Gizir (2017) on adolescents showed that the quality of adolescents’ relationships with their teachers and their peers increases their attachment to the school. Perdue, Manzeske and Estell (2009) found that the peer relations of third-grade primary school pupil predict how attached they will be to the school when they reach fifth-grade. They emphasized the meaningful contribution of friendships and the quality of support from friends to the sense of attachment to the school. In many studies in the literature, it was found that social competence was significantly associated with achievement at school (Márquez, Martín, Brackett, 2006; Welsh, Parke, Widaman and Neil, 2001; Wentzel, 1991) and positively correlated with adaptation to school and school connectedness (Simons-Morton and Crump, 2003). According to this, students who have a positive relationship with their peers and teachers are more attached and better adapted to the school. Given the fact that students spend a significant part of their school lives with their friends and teachers, the importance of interpersonal competence can be better understood.

Following this, studies on social relations and interpersonal competence show that interpersonal competence has an effect on the subjective well-being of the individual. This relationship may be direct or it may be through the perception of the school experience, which is consistent with the literature. It is possible that students who have more appropriate and effective relationships with their teachers and friends feel more attached to the school and have higher academic motivation. It is thought that the interpersonal competencies of students are important in terms of the experience of school. In other words, it is thought that the adolescents who are discussed in this study and who are able to initiate relationships, provide emotional support, reveal their strengths and resolve conflicts, perceive school experiences more positively.

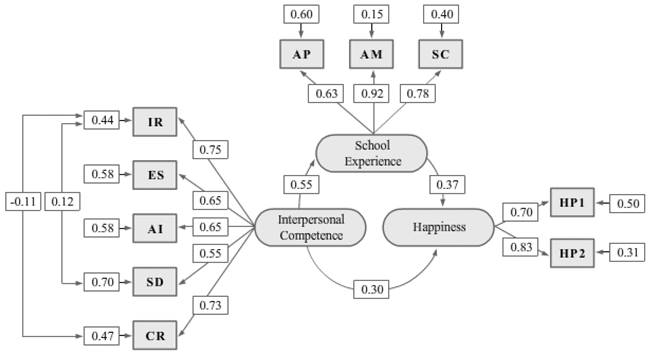

In this study, it was thought that interpersonal competence might play a role in the development of positive perceptions about school experiences and the perceptions of school experiences were considered as related variables. The intermediate role of the school experience perceived between interpersonal competence and subjective well-being was tested. For this purpose, the model shown in Fig. 1 was proposed.

Method

Sample

The participants of the study, selected through convenience sampling, consisted of a total of 268 students, including 104 females (39%) and 164 males (61%), attending various high schools in a city in the mid-Black Sea Region in Turkey. Participating students’ ages ranged between 14 and 18, with an average age of 16.22 (SD = 1.2). In the study, purposeful sampling method was employed. In direction of this purpose, the data was collected from high schools with different levels of success. 115 Anatolian High School, 70 Imam Hatip High School and 83 Science High School Students participated in the study. When the distribution of the students to the classes is considered; 114 students are in 9th-grade, 67 seven students are in 10th grade, and 87 students are in 11th grade.

Instruments

Interpersonal Competence Scale (ICS.) In order to measure interpersonal competence in close friendship relations, Buhrmester et al. (1988) developed a five-point Likert-type scale measuring five domains of personal competence (initiating relationship, asserting influence, conflict resolution, self-disclosure, providing emotional support). The scale consists of a total 40 items with eight items on each dimension. The Turkish adaptation of the scale was carried out on a group of adolescents by Baytemir (2014). The validity and reliability studies for the scale were performed on the data obtained from two different groups of adolescents. In the first and second studies, confirmatory factor analysis was used to test the validity of the scale and it was found that the model produced sufficient compliance values (First study: χ²/sd= 2.6, RMSEA= .059, CFI= .94, NFI =.94, GFI= .90; Second study: χ²/sd= 1.92, RMSEA= .054, CFI= .95, NFI= .95, GFI= .90). In the criterion validity study, the correlation coefficients between the subscales of the ICS and subscales of the Personality Test based on adjectives and the Adolescent Subjective Wellbeing Scale were found to be significantly related in the positive and negative directions. Reliability calculations showed that Cronbach Alpha values varied between .70 and .81 for subscales in both applications, and .90 and .91 for all scales. The test reliability coefficients obtained for five week intervals were found to be .85 for the whole scale and between .60 and .83 for the subscale.

School Experiences Scale . This scale was developed by Anderson-Butcher et al. (2012), to measure the perceptions of the individual about his/her school experiences. The Turkish version was by Baytemir, Kösterelioğlu and Kösterelioğlu (2015). The scale is a 5-point Likert-type scale and it consists of three dimensions and 14 items (Academic Monitoring: 1, 2, 3, 4; Academic Motivation: 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10; Reading Attachment: 11, 12, 13, 14.) The total score for the scale varies between 14 and 70. There are no reverse scoring items in the scale items. Confirmatory factor analysis for structure validity of the scale showed that the fit values were adequate (χ²/sd = 2.87, RMSEA = .057, SRMR = .039, CFI = .99, NFI = .98, GFI = .94). At the same time, it was found that the measurement incompetence was valid for both girls and boys. In the criterion validity study, it was found that the dimensions of the School Experiences Scale had correlations between .40 and .51 with the Perceived Social Competence Scale. It was also found that the School Experience Quality Scale had correlations between .30 and .75 with the subscales of "Teachers" and "Positive Feelings to the School". The item-total correlations for the reliability of the scale ranged from .48 to .79, and the t (sd = 211) values for differences in item scores of the 27% higher and lower groups according to the total scores ranged between 10.41 (p < .001) and 23.03 p < .001). The Cronbach alpha reliability coefficients for all the scales were .93, and ranged from .83 to .85 for the subscales.

Oxford Happiness Scale-Short Form. This scale was developed by Hills and Argyle (2002) and was adapted to Turkish by Doğan and Çötok (2011). A one-factor structure was obtained as a result of the exploratory factor analysis of the scale, which had an eigenvalue of 2.782 and explained 39.74% of the total variance. The one-factor structure of the scale was examined by confirmatory factor analysis and the goodness of fit indexes were found to be χ²/sd = 2.77, AGFI = .93, GFI = .97, CFI = .95, NFI = .92, IFI = .95, RMSEA = .074. In the context of scale-related validity, the relationship between the scale and the Life Satisfaction Scale was examined and a correlation at the level of .61 (p <.001) was found. The internal consistency coefficient of the scale was .74 and the test-retest reliability coefficient was .85. The Turkish form of the scale consists of 7 items (Doğan and Çötok, 2011).

Procedure

First, official permission was sought and received from the Provincial Directorate of National Education to collect data from the schools where the study was to be carried out. During the data collection, the adolescents were informed about the purpose of the study and they were asked if they would like to contribute to the study. Later, it was stated that this research was being conducted for a scientific purpose and that personal information would be confidential. The scales were given to the students who volunteered to participate in the survey. Data collection lasted approximately 20 minutes.

Statistical Analysis

Mahalanobis distance values were calculated to determine whether the data had extreme values that would damage linearity and normality. Nine observations (multivariate outlier) which had Mahalanobis distance values greater than χ²8;.01 = 20.09 were excluded from the evaluation. Values of kurtosis and skewness were examined to determine whether the data had a normal distribution. The skewness and kurtosis values were found to change between -1 and +1 (skewness: minimum-.07, highest-.64; kurtosis: minimum-.04, highest-.65). When correlations between variables were examined, it was found that the correlation values changed between .07 and .72, thus there was no multiple connection problem (Table X). The analysis of the data was carried out in the SPSS 21.0 and LISREL 8.8 programs. In the analysis of the data, the relations between the variables were analyzed by the Pearson Correlation method and the mediating relationship by structural equality modeling.

In this study, the happiness of adolescents was measured with a one-dimensional structure, therefore there was a need for indicators showing that the model was hidden in the structural equality model, and a parceling was made for this. The parceling application involves the mean or sum of two or more substances together. The average or sum of the results are used as a basic unit of analysis in the SEM. An advantage of the use of substance parcels is that parcels have a more uniform distribution and more normal distribution than individual items. Therefore, they are more suited to the common assumptions of normal-theory-based estimation methods such as maximum likelihood (Bandalos and Finney, 2001). The happiness latent structure was represented by two indicators by making parcels. First, during the parceling, the factor load values of each item were examined and ordered from highest to lowest. Then, assignment to the parcels was made according to the load value of factor, starting from the the largest factor load values. According to this, items 3, 5, 2 and 7 were assigned to the first parcel while the items 4, 6 and 1 were assigned to second parcel. The two-step approach proposed by Anderson and Gerbing (1988) for mediation analysis was used. According to this, the measurement model is examined for whether produces acceptable compliance values at the first step. If acceptable measurement values are found as a result of the measurement model, the structural model is tested. In other words, it is necessary to verify the structures to be examined before going into the structural model.

Measurement Models for Latent Variables

The measurement model created for this study is given in Figure 2.

As shown in Figure 2, it was found that the Standardized Path Coefficients changed between .55 and .92 and were sufficient. When the model fit values were examined in the first stage of the analysis, it was found that the fit measures were adequate but the RMSEA value was 0.09. When the subscales of interpersonal competence were related to each other as seen in the modification suggestion, the model's criteria were found to be sufficient (χ² / df = 2.73, RMSEA = .081, CFI = .96, NFI = .94, GFI = .94).

Results

In this section, descriptive statistics about the variables in the model are first given (Table. 1) and then the findings of the structural model test are listed.

Table 1: Correlation, means, and standard deviations of variables in the hypothesis measurement model.

As seen in Table 1, the subscales of interpersonal competence showed low and moderate correlations with perceived subscales of school experiences. Similarly, all dimensions except the self-disclosure dimension of interpersonal competence have significant relationships with happiness at low and moderate levels. Self-disclosure was found to be correlated with happiness 1 but not with happiness 2 which were indicators and they were parceled to define happiness. It was found that the subscales of school experiences were significantly associated with happiness at low and moderate levels.

When the results of the structural model for examining the proposed model were analyzed, all t values were significant (between 3.35 and 12.18). The analysis results for the structural model are shown in Fig. 3 and the compliance statistics are given in Table 2.

The structural model produced good and acceptable values (Table 2). According to Baron and Kenny’s method (1986), certain conditions must be met for the mediating relationship to be possible. When the measurement model (Figure 2) was examined, it was found that interpersonal competence (precursor variable) is related to happiness (result variable) as a first condition. The second condition was that the interpersonal competence which is the precursor variable, was associated with school experiences. According to the third condition, the school experiences perceived were associated with happiness. The model provides all of the conditions which were stated by Baron and Kenny in their method. When the influence of school experiences is controlled, it is expected that the relationship between interpersonal competence and happiness will be reduced or completely meaningless. When we looked at the standardized coefficient, we found that the distance from interpersonal competence to happiness had fallen from .50 to .30, so the t value was significant. In this case, it can be said that there is no full intermediary relationship. When the total effects were examined, the total effect of interpersonal competence on school life was found to be .55 (t = 6.85, p <.01) and the total effect on happiness was .50 (t = 5.83, p < .01). When indirect effects were examined, the indirect effect of interpersonal competence on happiness was found to be .20 (t = 3.75, p <.01). As a result, it can be said that school life plays a partial role mediating between interpersonal competence and happiness.

Discussion and Conclusion

According to the results of this study, it is seen that interpersonal competence predicted the perception of school experiences and happiness while the school experiences perceived predicted happiness. The school experiences perceived which were the main focus of the research had a partial mediating effect between interpersonal competence and happiness. The findings of this study seem consistent with the literature. According to the literature, interpersonal competence predicts the perception of experiences of school (Perdue, Manzeske and Estell, 2009, Simons-Morton and Crump, 2003). It is particularly emphasized that the relations with teachers and peers are important in the positive perception of school experience. Eccles et al. (1993) indicated that adolescents who are more social and accepted by their peers are more attached to the school than those who are socially isolated and rejected by their peers. Thus, an adolescent with interpersonal competence can start and maintain new friendships, resolve conflicts, say no when necessary, give emotional support to his friends, and practice timely self-discosure to his/her friends and teachers. Thus, high quality social relationships may emerge and the adolescents may be more motivated in school and more strongly attached to school emotionally. Otherwise, adolescents may have difficulty in participating in peer groups, they may have difficulty in saying no, or may be subject to extreme difficulties (Duy and Yıldız, 2014). At the same time, the student's degree of persistence, and his/her seeking help or support are important in understanding their motivation in school. Moreover, having interpersonal competence is related to better academic achievement (Welsh, Parke, Widaman and Neil, 2001; Wentzel, 1991). A student who is able to easily ask teachers questions and to discuss his/her issues with friends is better able to understand a topic. This student will probably gets high marks in exams. Thus, students getting higher grades from exams enjoy school more, and may be more attached to their schools. Goodenow (1993) emphasizes the need to increase the interpersonal competence of students who have low academic commitment and do not interact appropriately with their teachers and peers. An individual with increased interpersonal competence will be able to enter into more effective interactions, feel more attached to the school, and as a result, be happier.

According to the results of this study, the school experiences perceived were found to be a predictor of happiness. This finding is consistent with the literature. Many studies found a significant relationship between school experiences and happiness (Kidger, Araya, Donovan and Gunnell, 2012; Lent, do Céu Taveira, Sheu, Singley, 2009; Stiglbauer, Gnambs, Gamsjäger and Batinic, 2013). It seems quite plausible that adolescents feel happy when they feel a sense of belonging to the school and that this gives them a stronger academic motivation. Students spend the significant part of their daily lives in school. A student who does not like school, who does not have good connections, and whose academic achievement is low, is hardly likely to be happy at school. For example, the study of Yıldız and Kutlu (2015) on adolescents showed that students with a low degree of attachment to their school feel more alone. Depressive symptoms are seen in the students when the sense of belonging to the school is weak (Joyce and Early, 2014; Schwerdtfeger Gallus, Shreffler, Merten and Cox, 2015). Following this, it can be considered that a sense of belonging makes the student happier and that without it the student is lonely and unhappy. In addition, teachers who motivate students to be successful can make students feel a greater sense of belonging to the school and thus happier. The satisfaction students feel in schools also increases their happiness. A student who feels him/herself to be academically adequate and who has positive social relations may feel happier. A student who can choose his/her own activities and willingly participate in courses feels happier. According to the results of this study, interpersonal competence predicts the happiness of adolescents. This finding is consistent with the literature. In many studies, interpersonal competence was found to be a determinant of happiness. In adolescence, peer relations are especially important. Belonging to a group and being active in a group are the most basic desires of adolescents. At the same time, the physical, social and emotional changes experienced in adolescence may cause them to feel shy or anxious from time to time. Adolescents may isolate themselves even though they want to join a group, to feel influential and to be closer to their teachers. An adolescent with interpersonal competence can better manage her/his development and thus feel better. The focal point of the study was the mediating role of school experiences between interpersonal competence and happiness. Therefore, the relationship between interpersonal competence and happiness in adolescents may occur directly or indirectly through school experiences. As the adolescents increase their interpersonal competence, their perception of their experiences of school become more positive and this makes the adolescents happy. Diener and Seligman (2004) state that good social relations are effective in creating and maintaining of subjective well-being. Having adequate interpersonal skills can play an important role in the happiness of adolescents. Adolescents with strong social affiliations are more likely to participate in events, have better peer and teacher relationships and have more academic success, thus school becomes attractive for them. It has long been known that group work influences students’ social, emotional and mental development. A student who communicates effectively with colleagues will be more successful, learn more and enjoy more. Thus, a student who loves school, who has a good relationship with his friends and teachers, and who is academically successful will have more positive feelings and he/she will obtain more satisfaction from life.

In line with the results obtained from the study, it can be said that interpersonal competence is important in the positive perception of school and that it increases the happiness of adolescents. Psychological counselors and school psychologists may be able to use individual and group work to increase the interpersonal competence of students. It could be given priority in improving skills such as interpersonal conflict resolution, the ability to say no, initiating relationships and self-disclosure at the appropriate time and place among adolescents who are often absent, who avoid participating in group work and who do not feel connected to their schools. Positive perceptions of their experiences at school make adolescents happier. When both school mental health professionals and staff working at schools follow up students more, offer more activities and lessons that students can choose voluntarily, are more interested in students and assign tasks that students can do, this may make the students happier. In every period of life, it is important to belong to one or a group, especially during adolescence. Adolescents' interpersonal competencies can be improved by devoting more time to group work, projects and social activities, so the adolescents can perceive school more positively and be happier. It was seen in PISA 2015 Report that the 15 years old-age group students in Turkey have lower life satisfaction and sense of belonging to the school, and higher academic stress in comparison to other OECD country students. Therefore, allocating more time to activities and extracurricular activities that provide more interaction opportunities to students and support their interpersonal skills in high school programs in Turkey might enable students to have more positive feelings towards school and perceive their school experience more positively. Accordingly, happiness levels of students who are satisfied with their school experience may increase. In this study, interpersonal competence predicts the perception of school experiences. In this context, interpersonal competence increases the self-esteem of the adolescents or the quality of friendships, so the perception of school experiences may be positive. For this reason, the relationship between self-esteem and friendship, and what mediates this, can be examined. Exposure to bullying is one of the major problems that adolescents have at school. Bullying is one of the major problems that adolescents experience in school, and students who are exposed to bullying may perceive school experiences less positively. The relationship between interpersonal competence, bullying and school experiences can be determined. Dropping out of school may be related to the perceived negativity of school experiences and dislikes about the school. The role of these interpersonal competences in this relation can be studied.

The sample group of this study consists of adolescents who receive education in different high schools in different class levels. Therefore, it should be considered in terms of generalizing that the study is limited with the high school students in a specific region of Turkey. Students’ perceived school lives may vary from culture to culture. As it was stated in PISA 2015 report, adolescents' sense of belonging to school or their life satisfaction differ according to countries more or less. In addition to this, academic demands from the student increase with a higher class level in all education systems. In this study, a model was proposed on the basis of literature. For this reason, both national and international studies were included during the literature review. According to the literature, students perceive their school experiences more positively with an increase in their interpersonal competence, social competence, and social skills. Once again, happiness levels of students increase with an increase in their interpersonal competence and with positive perceptions towards school. With reference to the literature and the results of the model that was tested in this study, this study can be tested for the adolescent groups in other countries. While the mediation of this study might be stronger for the students from the countries where the school experience is perceived more positively, it might be weaker for the students from countries where the school experience is perceived less positively. In this way, this model can be tested both in different cultures and different high school types, and in different class levels.