Introduction

Health professionals from different areas are involved in caring people on a daily basis, taking this experience with emotional fluctuations, that demand certain coping capacities (Bermejo, 2018; Bermejo, Díaz-Albo & Sánchez, 2011; Bermejo, 2012) for their own well-being and also, to be able to establish healthy aid relationships. Care for people exposes the caregiver to a series of complex experiences that are described below, and which are classified in negative (compassion fatigue and stress, burnout or empathy fatigue) and positive (compassion satisfaction, vocation or happiness) emotions.

Within the field of negative experiences, it should be noted that Figley (2001) developed a compassion stress and fatigue model, defining the latter as the capacity in being empathic or “bearing the suffering of others”; an extreme state of tension and preoccupation with the suffering of those being helped to the degree that it is traumatizing for the helper (Figley, 2002). On the other hand, burnout is defined as a psychological syndrome emerging as a prolonged response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job. It is identified by an overwhelming exhaustion, feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment (Leiter & Maslach, 2004).

Likewise, compassion fatigue, is defined as the “natural, predictable, treatable and preventable consequence of working with people who suffer; it is the emotional residue resulting from exposure to work with those who suffer the consequences of traumatic events”, and caused by the lack of tools to manage our own suffering, the patient´s and his/her family members (Acinas, 2012).

Empathy entails warmth in a relationship, an emotional proximity that must be self-regulated to avoid losing therapeutic distance, (Bermejo, 2012; García Laborda & Rodríguez Rodríguez, 2005) something considered as positive, as long as it doesn´t lead to cool the relation with the patient or develops into burnout, due to a poor management in the distance of the emotional involvement (Bermejo et al., 2011).

On the other hand, the Job Demands-Resources model has been described as a tool to predict burnout, organizational commitment, work connection and engagement, and it is also useful to predict possible consequences that could arise, such as sickness absenteeism, job performance and employee well-being (Bakker & Demerouti, 2013). It seems that workload and healthcare demand are associated with emotional exhaustion; in this regard, Burke & Richardsen (1996) considered that burnout scores are always higher in work environments characterized by an excessive workload.

In recent years, most of the research has been focused on burnout and its effects, which hides a much more satisfactorily side of reality. The care of people can imply what has been called, compassion satisfaction (CS): the positivity resulting from caring (Phelps, Lloyd, Creamer, & Forbes, 2009), taken as the “ability to receive gratification from caregiving” (Simon, Pryce & Klemmack, 2006) or as the selflessness and positive feelings resulting from the ability to help. Within the job performance of healthcare professionals, CS is associated with an understanding of the healing process, an internal self-reflexion, a connection with fellowmen, an increased sense of spirituality, and a higher degree of empathy (Hernández García, 2017); it also has its own measuring instrument called the Compassion Fatigue and Satisfaction Test (Stamm, 2010). According to some authors, a proper management of self-compassion helps professionals to reduce stress and prevent burnout (Aranda Auserón et al., 2017).

Palliative care professionals who are in permanent contact with situations that expose suffering, have similar levels of anxiety and depression that colleagues in other healthcare areas or specialties, but they pose lower levels of burnout, since they work with their own objectives and philosophy, along with an on-going training and education which helps them to prevent it (Pérez, 2011).

Within this context, we can talk about vocation, defined as a mankind inner call that connects feelings, experiences, awareness and emotions; it is a connection with a desire for happiness expressed as a passion towards a specific field or happiness, in the professional area (Buceta, 2017). It happens on a daily basis, and it may also be influenced by depersonalization, burnout syndrome or stress.

Attachment works in the same way because the importance of interpersonal relations for the well-being of individuals is an undeniable fact, and attachment styles reflect the perception a person has on the receptiveness and responsiveness to oneself and others (Yárnoz et al., 2001); and here is where self-compassion makes its appearance, defined and studied by Neff (2003) as being kind and understanding towards oneself in instances of pain and failure. Neff (2003) states that self-compassion involves interconnected components that can emerge when confronted with emotional pain situations, entailing positive aspects such as self-kindness, common humanity and mindfulness, and negative ones, such as self-judgment, isolation and over-identification (Araya & Moncada, 2016).

In order to evaluate the experience of the described emotions, Stamm (2010) developed the concept of professional quality of life; quality of emotions having opposite sides: compassion satisfaction (CS) and compassion fatigue (CF). CS contributes to psychological well-being by alleviating the negative effects of the professional activity (Mathieu, 2012); it is also related to work satisfaction (Salessi & Omar, 2016), by showing a sense of competence, pleasure and control in one´s own work, which may become a coping strategy to those who devote themselves to end of life care (Barreto, 2014).

Likewise, Herzberg (as quoted in Rodríguez Alonso, Gómez Fernández, & De Dios del Valle, 2017) proposed the two-factor theory in which he contends that job satisfaction is contingent upon the existence of two groups of factors, that give meaning to the nature of one´s work; these are extrinsic factors that can only prevent or avoid work dissatisfaction, and intrinsic factors, which result in satisfaction.

Nowadays, there is some interest in studying the effects of the cultivation of compassion in the relationship with patients, which includes factors such as compassion fatigue and stress as elements that make professionals work difficult. Compassion fatigue causes physical and emotional exhaustion, and a behaviour that can lead to depersonalization similarly to burnout syndrome. However, an appropriate management of self-compassion helps professionals to reduce stress and prevent burnout (Aranda Auserón et al., 2017). The relation among the variables described can lead to a humanized care that may include satisfaction, compassion and vocation happiness or on the contrary, to the opposite side, which can result in fatigue, burnout and exhaustion.

For all that, the purpose of this work was to study the potentially humanizing factors or compassion satisfaction triggers in healthcare professionals; in particular, the relation of adult attachment styles, self-compassion, vocation, level of healthcare demand, people care satisfaction, work satisfaction and burnout, were analysed with the feeling of compassion satisfaction.

Methods

Participants

480 assistentially active health professionals replied to the questionnaire. Most of them (79.6%; 382) were women, with an average age of 44.6 years (SD = 10.86), married or in a relationship (58.3%; 280) and with more than 8 years of working experience (69%; 331). The largest group have nursing education (29%; 139), work in the Community of Madrid (58.8%; 282), in the field of dependent and elderly care services (25.6%; 123) or in medical-surgical treatment and rehabilitation areas (25.2%; 121) (Table 1).

Instrumentation

A self-report was used (Annex) to collect:

Socio-demographic variables: age, gender, marital status, education and job location.

Working experience variables; years working in the healthcare field (annex, question No 6), healthcare demand perceived (No 7), vocation (No 10), work team satisfaction (or socio-labour support) (No 11), caring satisfaction (No 12) and emotional description of working experience (No 13 to 17).

In order to assess the levels of burnout (or feelings of hopelessness resulting from work) and Compassion satisfaction (or the pleasure resulting from the ability to do well in one´s own work), the Spanish version of ProQoL (Stamm, 2002), and Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue ProQoLvIV (Morante, Moreno & Rodríguez, 2006) questionnaires were used. Twenty items from the burnout and compassion satisfaction dimensions were taken and rated with the Likert type scale (from 0 to 5). In this study, the 10 items of the CS scale obtained an internal consistency of .84 measured according to Cronbach’s alpha, while the 10 items of the burnout scale obtained .7.

In order to assess self compassion, the Neff (2003) self compassion scale in its Spanish version (García-Campayo et al., 2014) was used. This 26 items questionnaire, rated by using the Likert type scale (from 1 to 5), measures the level of kindness and appreciation towards oneself, as a human being aware of its own deficiencies. It evaluates six opposed aspects (in italics); self kindness as an alterative to self-judgment, feelings of belonging to a common humanity as an alternative to isolation, and complete care as alternative to over-identification with one´s own feelings and emotions (Neff, 2003). In this study, the complete scale obtained a Cronbach α of .91, and the subscales ranged between .73 (common humanity) and .84 (self-judgement).

Lastly, in order to assess attachment styles (or strategies to organise and regulate emotions and cognitions about oneself and others, Bowlby, 1988), the RQ or Relationship Questionnaire (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991) in its Spanish version (Yárnoz-Yaben, 2008) was used, rating the four items in a scale from 1 to 7, and identifying the attachment styles by considering the participant´s own self-identification. The four category model of attachment styles include: secure style, suitable for people that experience positive and negative relations and whose representation of oneself and others tend to be positive; dismissing style, characterized by experiences with inaccessible attachment figures, and preoccupied and fearful styles, that corresponds to those who experience an unpredictable affordability (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991).

Procedure

A convenience sampling was applied (not probabilistic) since participants were selected by their accessibility to the researchers behind the study. The questionnaire was uploaded into Google Drive, and requests were sent to healthcare professionals to complete it by using social networks (of the authors of the study), and email addresses (of the databases of the two centres where the study was carried out). That is to say, it was sent to staff primarily related to the healthcare field at different levels, from vocational training to college, mainly located in the Community of Madrid, but also in places of the rest of Spain and Latin American countries, since there is a working relationship with them from the centres where the study was taking place.

Data collection ended after 4 weeks.

Statistical analysis

For the purpose of describing the characteristics of the sample regarding socio demographical variables, and the scoring achieved in each scale and subscale, descriptive ratio statistics were used. Likewise, with a view to describe and identify differences between profiles, Student´s T-test was used for independent (in the case of groups with categorical variables) and paired (in the case of intrasubject comparisons) samples. In the event of comparing more than two groups, one-way ANOVA was used.

An analysis of word frequency was carried out using the qualitative data analysis software NVivo 11.0, with the aim of carrying out an emotional description of the working experience.

Pearson correlations were used in order to find associations between the main variable in the study (compassion satisfaction), and the other quantitative variables collected (adult attachment styles; self compassion scales and subscales; vocation, healthcare demand, people caring satisfaction, work satisfaction and burnout levels).

Finally, backwards hierarchical multiple linear regression (MLR) was also used to assess the individual impact (eliminating the effect of other variables) of possible predictors of compassion satisfaction (as dependent).

The software SPSS v20 was used to complete this task.

Results

Qualitative analysis of open-ended questions

Participants provided 5 words to describe their emotions in the workplace by using free text. After converting free text into equivalent key words (e.g.: “a lot of empathy”, changed into empathy, tired into tiredness or satisfied into satisfaction); the 10 most repeated words that participants used to describe the emotions resulting from work were: useful (184 repetitions; 7.6%), satisfaction (177; 7.3%), happiness (145; 6.04%), fulfilment (127; 5.29%), responsibility (118; 4.9%), good (83; 3.4%), fatigue (75; 3.1%), valued (59; 2.4%), human (56; 2.3%) and gratitude (51; 2.1%) (Figure 1). It should be noted that this frequency analysis, in its qualitative variable, changes into feelings with a positive meaning (9 out of 10) in relation to compassion satisfaction.

Mean comparisons

Means obtained in scales, subscales and variables on working experience are shown in table 2. Scoring of scales and subscales with the same number of items were compared, (attachment styles were compared to each other as well as self-compassion subscales; self-judgement and self-kindness scores were weighted); satisfaction compassion scale was compared to burnout, and the scoring obtained was compared to the rest of the other variables in relation to each other. The differences obtained among the scoring of the four attachment styles and between the scales of compassion satisfaction and burnout (23.37 points) were statistically significant (p < .001), being the highest scores those of secure attachment and CS. The differences among the means of the four variables on working experience were also statistically significant (p < .001), being vocation and caring satisfaction the ones getting higher scores.

Table 2: Statistical descriptions of the scoring obtained in the scales and subscales of the study questionnaires, in the variables of work experience and the results of mean comparisons (Student´s T-test for paired samples).

In doing the comparison of all variables included in table 2 between men and women, only burnout, self-judgement and over-identification had significant results (p < .05); it was higher in women (mean of 18.6; 13.6 and 10 respectively) than in men (mean of 16.4; 12.4 and 9.2). Neither marital status (singles n = 200 vs. in a relationship n = 280), nor location (Community of Madrid n = 282 vs. rest of Spain n = 165) showed significant differences between them.

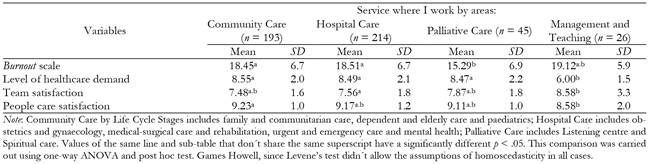

With regard to the different services provided, professionals working in the Palliative Care area obtained the lower mean in the burnout scale (15.3), the second higher mean were in self-compassion (93) and working team satisfaction (7.9), but none of them were statistically significant; so, in seeking to maximise the statistical power, the services were grouped into four healthcare areas according to the idiosyncrasy of the work performed in them: Community Care by Life Cycle Stages, Hospital Care, Palliative Care and Management and Teaching (n = 26) and then, the analysis was conducted again (Table 3).

Table 3: Mean comparison results (one-way ANOVA) between the different groups of service areas, with respect to variables that obtained significant differences.

There were only significant differences (p < .05) in burnout, work team satisfaction, care satisfaction and health care demand scales; Palliative Care obtained a lower mean in burnout scale than Community Care and Hospital Care (15.3 vs. mean of 18.5). Management and Teaching, even with an small n, distinguished from the other groups in regards to the lower level of health care demand it registers (mean of 6 vs. mean of 8.5; p < .05); it obtained higher work team satisfaction than Hospital Care (8.6 vs. 7.5; p < .05), and lower people care satisfaction than Community Care (8.6 vs. 9.2; p < .05).

Regarding different occupations (using one-way ANOVA and Tukey HSD post hoc test, since Levene’s test didn´t allow the assumption of homoscedasticity in all cases), it was found that assistant nurses obtained significantly higher mean (p < .05) in compassion satisfaction (44.2) than doctors (40.2) and psychologists (40.7); in self-judgement, their mean was lower than in other healthcare professionals (12.0 vs. 14.8); and in over-identification, their mean was lower than that of doctors (8.6 vs. 10.6). Likewise, psychologists obtained a mean (p < .05) significantly higher (18.4) than nurses (16.3), doctors (16.1) and other social workers (15.1). In the rest of variables, the different occupations did not show significant differences.

Correlations between the variables in the study

Table 4 shows CS and burnout correlations with the rest of the variables; mostly all of them are statistically significant. Significant (p < .001) and direct correlations of CS with secure attachment, self-compassion, self-kindness, mindfulness, variables related to working experience are highlighted, as well as reverse variables with burnout, isolation and over-identification.

Multiple linear regression with compassion satisfaction dependent variable

MLR included four types of attachment, six scales of self-compassion, burnout scale, and also gender, age, professional experience, healthcare demand, vocation, team satisfaction and people caring satisfaction scales.

A compassion satisfaction predictor model was obtained, that explained 51.5% of the variability (corrected R 2=0.515), and left the following predictor variables: caring satisfaction, vocation, self-kindness and burnout, (table 5). Self-judgement, dismissing attachment, team satisfaction, and isolation variables obtained significant Beta (p < .05), but they were eliminated of the model because of their low contribution to adjustment (squared semi partial correlation coefficients smaller than a tenth), which resulted in the following regression equation (with non standardized B coefficients):

Compassion satisfaction = 19.098 + (1.469 * caring satisfaction) + (0.75 * vocation) + (0.23 * self-kindness) - (0.252 * burnout)

Discussion

The purpose of this work was to study the potentially humanizing aspects of healthcare professionals. The relations found among the selected variables just as the characteristics that define the sample, discussed below, allow establishing humanizing factors or compassion satisfaction emotion triggers, as well as dehumanizing factors or burnout triggers.

Feelings of work vocation and a high degree of people caring satisfaction are observed, as well as a high level of healthcare demand, except in the Management and Teaching areas (where patient care does not apply). In this sample, the level of compassion satisfaction is much higher than that of burnout. For this reason, the most repeated words evoke positive emotions that are far from professional fatigue or dehumanization: “useful”, “satisfaction” and “happiness”. As it happens in other studies which conclude that most professionals in healthcare areas are satisfied (Carrillo, Martínez, Gómez, & Meseguer, 2015), our results suggest that professionals in this sample feel generally fulfilled in their professional area, since their work generates pleasant and encouraging emotions.

With reference to personal characteristics, secure attachment style was the most prevailing, which entails a low anxiety factor in relations with others. Regarding self-compassion, the tendency observed in this study is to view oneself in a comprehensive and positive way (self-kindness), with a sense of persistent common humanity that recognizes both, the limitations and virtues of others as well as one´s own (common humanity). It also enjoys a balanced attitude that observes and connects with one´s own personal emotions (complete care) (Neff, 2003).

Both, in the results of the sample correlations and MLR, the factors that emerge with higher humanizing power include to feel caring satisfaction, feelings of vocation in the workplace, self-kindness and, as it would be expected, the absence of burnout. Furthermore, self-compassion (the three positive scales defined in the introduction) and the secured attachment bond, from the four attachment styles, are directly linked to compassion satisfaction and inversely linked to burnout; for that reason, it can be asserted that those who show kindness and common humanity towards their own, and have the ability to mind and to accept what happens, along with an attachment relation that combines a positive idea of themselves and of others (secure attachment), will provide a satisfactory compassionate treatment to patients, and will find happiness in their care; and this happens because when the professional analyses its own work and shares pain with patients, his/her own life is challenged and this is something that helps him/her to grow (Buceta, 2017).

These factors (self-compassion, secure attachment, compassion satisfaction) along with age can be considered as protector factors against burnout. On the contrary, those factors that in this study are related to burnout syndrome are, preoccupied and fearful attachment and lack of self-compassion (or its three negative scales: critical judgement, feelings of isolation and over-identification).

Regarding the incidence of burnout depending on the services provided, this study confirms a lower level of this syndrome in Palliative Care (Pérez, 2011). Taking care of someone who is suffering causes a number of rewards such as calmness, growth, and also adds value to human life, which along with the closeness to patients, protects them from burnout syndrome (Buceta, 2017).

The model obtained in this study explains more than half of the variability in the sample (51%), which allows to establish that compassion satisfaction appears in those subjects that experience caring through self-kindness, caring satisfaction and vocational experience, and who distance themselves from burnout. This way we can state that compassion satisfaction brings the caregiver closer to the patient, connects with him/her, and helps professionals to manage their feelings or emotions. However, those who experience caring as fatigue and manage their work in a bad way, distance themselves from the person cared, and dehumanize their assistance.

Those variables that were eliminated for their low distribution to model adjustment (self-judgement, dismissing attachment, work team satisfaction and isolation), could influence on compassion satisfaction, but they won´t do it without the effect of the rest of variables on satisfaction. Factors under discussion such as age, gender, experience in healthcare areas, or level of healthcare demand, neither seem to be significant. We consider this fact one of the limitations of the study, since its interpretation is questionable. It seems difficult to imagine human beings who can statistically compartmentalise their experiences and prevent some variables from affecting others. In other words (Stamm, 2002), the relationship between fatigue and compassion satisfaction is not clear, there is a balance between them in which both affect each other.

Lastly, the possibility of having generated an anchoring effect between the questions related to vocation and satisfaction work experience (10, 11 and 12) and the five open-ended questions (13 to 17) is given, since there is a relation between the content of the first ones and the results obtained in the open-ended questions; more specifically, the second most repeated word was “satisfaction”. Nevertheless, since sometimes people´s experiences when caring are beyond numbers, we consider that a qualitative approach would be really useful in the future.

In conclusion, and as a fundamental practical implication of the study, it follows that caring satisfaction, vocation to work, self-kindness and lack of burnout have a direct and positive impact on compassion satisfaction, while mindfulness, common humanity emotions, secure attachment and work team satisfaction affect it indirectly. Thus, these are humanizing and protector factors against burnout, a syndrome that is directly related to preoccupied and fearful attachment styles, lack of self-compassion, self-judgement, over-identification and isolation.

text in

text in