Introduction

Eating disorders (ED) are still one of the main health problems of today's society, especially in women and young populations. Although there are numerous studies that provide data on the prevalence of the problem, there is a tendency to ignore or underestimate the number of women and men who are at risk of developing these disorders, due to certain psychological characteristics and perform risk behaviors.

The ED are characterized according to the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) because it is a persistent alteration of feeding or behavior related to food, which leads to an alteration in the consumption or absorption of food and which causes a significant deterioration of physical health or psychosocial functioning. These disorders involve a distorted eating behavior and an extreme concern for self-image and body weight, which motivates the adoption of inadequate strategies to prevent weight gain, such as vigorous physical activity and drastic restriction of intake (Herpertz, 2009).

At the base of ED, both in its beginning and in its maintenance, a series of relevant psychological variables have been pointed out. The obsession with thinness, or the desire to be thinner and the preoccupation with feeding, weight, and the fear of getting fat, is a central element of ED symptoms in clinical samples, and is also an important factor in risk for the development of symptoms in non-clinical samples (Elosua, López-Jáuregui, & Sánchez, 2010; Garner, 2004). Also, body dissatisfaction has been assumed as one of the most relevant factors to understand the origin of ED (Beato, Rodríguez, Belmonte, & Martínez, 2004), and is also associated with the worsening of these pathologies (Cooley & Toray, 2001). In fact, a specific criterion for anorexia nervosa of the DSM-5 (APA, 2013) is the alteration in the way in which one perceives one's own weight or constitution, and in ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1992) the specific distortion of body image is pointed out as diagnostic criterion. Similarly, low self-esteem is considered a basic risk factor for the development of ED (Vohs et al., 2001), and a fundamental factor in both anorexia and bulimia (Striegel-Moore, 1995). In addition, other variables such as perfectionism, problems of self-esteem and self-concept, defective coping skills, and certain psychopathologies, such as anxiety, depression, and obsessive or compulsive disorders, have shown their relationship with ED to a greater or lesser extent (Castejón, 2017; Pamies, 2011).

Also, personality analysis in relation to eating disorders has played an important role in research. The different conceptual models indicate that the personality can be considered as a predisposing factor, as a complication, or as an influence, although the absence of long-term prospective studies has prevented clarifying this unknown (Caramillo, Khan, Collier, & Echevarria, 2015).

Currently, the different investigations that study the role of personality factors in ED are based mostly on the conceptual model of the Big Five (McCrae & Costa, 1999). Cassin and von Ranson (2005) consider that personality is involved in the appearance, expression and maintenance of ED. In their studies they found, both in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, high levels of perfectionism, obsessive-compulsive traits, neuroticism, negative emotionality and avoidance of harm together with low self-directivity and cooperativity. They concluded that patients with bulimia present a greater search for novelty and impulsivity than patients diagnosed with anorexia. Consistent with these results are those obtained by García-Palacios, Rivero and Botella (2004), who found that patients with ED score higher than case-controls in neuroticism and lower than them in extraversion and agreeableness.

Precisely, the relationship between high neuroticism, perfectionism and ED is one of the most consistent findings in this field (Claes, Vandereycken, Vandeputte, & Braet, 2013, García-Palacios et al., 2004, MacLaren & Best, 2009; Podar, Jaanisk, Allik, & Harro, 2007). Studies like those of Bulik et al. (2006) and Lilenfeld, Wonderlich, Lawrence, Crosby and Mitchell (2006) support the possibility that both neuroticism and perfectionism suppose ED risk factors.

At the same time, dissatisfaction with weight and body shape, and the search for thinness, can trigger a series of inadequate behaviors related to feeding and weight, which pose a risk for the development of some type of ED (Stice, Marti, & Durant, 2011). Some of these behaviors, known as risky eating behaviors, are the use of excessive physical exercise, binge eating, the monitoring of chronic and restrictive diets, the abuse of laxatives, diuretics or amphetamines, self-induced vomiting and the practice of fasting (Altamirano, Vizmanos, & Unikel, 2011; Saucedo, Peña, Fernández, García, & Jiménez, 2010), which are associated with harmful consequences for health, such as malnutrition, deficits of essential nutrients or physiological alterations of various types (Lora-Cortez & Saucedo, 2006; Resch & Sezendei, 2002).

A high risk population is university students. In university environments, ED have a high prevalence (Kwan et al., 2014, White, Reynolds-Malear, & Cordero, 2011), as well as a high level of risk behaviors mentioned above (Perryman, Barnard & Reysen, 2018; White et al., 2011). The period of university life can be considered an especially sensitive and stressful stage, due to the numerous changes and challenges that young adults must face (Trindade, Appolinario, Mattos, Treasure, & Nazar, 2019), as the need to adapt to the new social roles, the loss of family or social support when changing homes, living with people of different sociocultural origins, financial difficulties, and the need to organize work and study schedules, among others. All those stressful life events can affect the mental health of students and lead to different problems, such as ED (Loth, van den Berg, Eisenberg, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2008).

In addition, an important aspect is that the vast majority of epidemiological studies have consistently stated that the risk and prevalence of observed ED are higher in women than in men (Álvarez-Malé et al., 2015; Calado, 2011; Castejón, 2017, Dooley-Hash, Banker, Walton, Ginsburg, & Cunningham, 2012, Galmiche, Déchelotte, Lambert, & Tavolacci, 2019, Martínez-González et al., 2014, Pamies, Quiles, & Bernabé 2011). Even the DSM-5 (APA, 2013) states that anorexia nervosa is an eminently female disease. However, many studies do not make a gender distinction, and existing ED assessment instruments provide data and scales based primarily on female samples that impede comparisons with men. That is why, considering these gender differences, it is essential that the studies analyze each sex separately.

Therefore, the aim of the study was to compare the differences in personality and psychological variables related to ED, in women and men, from the fulfillment of specific criteria from which the referral to a specialist in these pathologies is recommended.

Method

Participants

The study involved 604 subjects, 398 were women (65.89%) and 206 men (34.11%), with an average age of 22.54 years (SD = 4.25), and a range of ages between 18 and 36 years. No participant was diagnosed with ED, nor had it been previously.

All the participants were university students from public and private universities of Murcia and Málaga (Spain), studying degrees in Primary Education (39.24%), Early Years Education (33.77%) and Physical Activity and Sport Sciences (26.99%). The highest percentage of students were in their third year (30.63%), followed by those who were in their fourth (23.68%) and second (23.01) years, and finally the students in their first year (22.68%).

Instruments

Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3). EDI-3 was used, original by Garner (2004) and adapted to Spanish by Elosua et al. (2010). It is composed of 91 items, organized into 12 main scales, three specific scales of ED and nine general psychological scales not specific to ED. The first three are called ED risk scales, specifically drive for thinness, bulimia and body dissatisfaction. The remaining nine scales evaluate psychological constructs that are conceptually relevant in the development and maintenance of ED: low self-esteem, personal alienation, interpersonal insecurity, interpersonal alienation, interoceptive deficits, emotional dysregulation, perfectionism, asceticism, and maturity fears.

The questionnaire presents adequate psychometric properties, since Elosua et al. (2010) in their adaptation work from a clinical sample, obtained factorial structures similar to those of the original version. In addition, the reliability of a clinical sample of 512 patients (97.7% women) and a non-clinical sample of 5148 (50% women) was satisfactory.

Eating Disorder Inventory. Referral Form (EDI-3 RF). This referral test by Garner (2004) is a short version of the EDI-3, and is intended as a screening test, to allow an evaluation of the need to refer the subject to a specialized service in eating ED. It evaluates the risk of developing ED through the 25 items in three main scales (drive for thinness, bulimia and body dissatisfaction). Since these data were obtained with the previous instrument, the EDI-3 RF uses part B, which contains different questions about the demographic data of the subject and his weight history (age, sex, height, current weight and the weight the subject would like to have), and the frequency of risk behavior to control weight (presence of binge eating, vomiting, use of laxatives and exercise to control weight, and if in the last six months the subject has lost 9 kilograms or more).

The instrument is based on the application of a series of simple and clear decision rules. To do this, it includes three criteria from which the subject must be referred to when in one of the three the point of cut is exceeded. In addition, the EDI-3 RF includes specific questions to collect information on weight and height that are used to calculate the BMI.

After calculating the BMI of the subject, it is contrasted if it meets any of the following referral criteria:

Referral criteria based only on the BMI: the remission criterion is met if the subject's BMI is equal to or lower than the critical value indicated in the instrument for different ages and sex.

Criterion of referral based on the BMI plus the presence of excessive concern about weight and food: the BMI correlates positively with drive for thinness and bulimia scores, so that different critical values are established for both scales in function of the BMI and the age of the subject. The remission criterion is met if the total direct score of the scales of the subject is equal to or greater than the respective critical value proposed.

Criterion of referral based on behavioral symptoms: it must be verified if any of the responses that the subject provides about binge eating, vomiting, use of laxatives, physical exercise and weight loss meet the criteria. To check this, we must see if the subject's score in any of these questions is within the critical range. If one or more are verified (the subject has surrounded at least one Yes in the table), the subject is considered to meet the referral criteria.

Through these scores, valuable data are obtained for the evaluation, but they must be interpreted with caution, since a clinical interview must subsequently be conducted in order to establish a diagnosis (Garner, 1991, 2004).

Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI). To obtain the data on personality traits the Spanish adaptation of the NEO-FFI was used (Costa & McCrae, 2008), a reduced version of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (Costa & McCrae, 1992). The instrument is composed of 60 items and allows the rapid assessment of the five major personality factors: neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness and conscientiousness. The NEO-FFI, both in its original version and in its Spanish adaptation, presents adequate psychometric properties and a good internal consistency in all dimensions.

Procedure

Once the aims of the study were set and selected the type of population on which the research was to be carried out, the pertinent permission was requested from the universities. After receiving authorization to conduct the study, the teachers responsible for the groups that were to participate were contacted, to which a detailed report was sent on the aims of the study, the duration of the study and what the work would consist of. It was going to be done with the students, as well as the benefits that the work could bring them.

The questionnaires were administered collectively, anonymously and voluntarily during class time. The students were informed that a study was going to be carried out on Eating Disorders and Personality, of the confidentiality treatment that the data provided would have and their collaboration was requested. Obtained the approval of the same, after informed and signed consent, the battery of questionnaires was administered.

Those responsible for the research were present during the administration of the questionnaires to provide help if necessary, to verify the correct and independent completion by each subject.

Data Analysis

Several types of analysis were carried out. Pearson’s Chi-square test (χ 2) was used to test the hypothesis of association between variables and to determine whether the differences observed between women and men were sufficiently relevant. Student's t-test for independent samples was used to examine the differences between means in all the scales evaluated, and to determine the magnitude of the differences found the effect size (d) of Cohen was calculated. To analyze the differences between groups according to the number of criteria met, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used, and the eta-squared statistic (η 2) to quantify the magnitude of the differences. To carry out all the analyzes, it was used IBM SPSS Statistics v. 24.

Results

First, a comparison is made between women and men in risk and psychological scales of the EDI-3 and personality factors (Table 1).

In risk scales, there are significant differences (p< .001) in relation to the gender in drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction, although there are no significant differences for the bulimia scale. Women have higher averages in both. In the nine scales that evaluate psychological constructs, there are significant differences between women and men in low self-esteem, asceticism and perfectionism (p < .05), although effect size is of small magnitude. Regarding the NEO-FII factors, women obtained in all higher means, finding significant differences (p <.01), in relation to gender in neuroticism, agreeableness and conscientiousness scales.

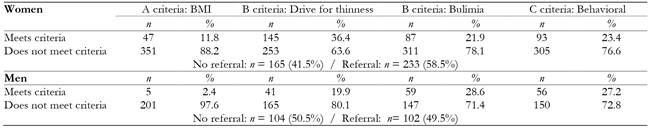

Then, a comparison is made between women and men regarding the remission criteria as shown in Table 2,

In first (BMI-Age-Sex), 47 women (11.8%) and 5 men (2.4%) meet the referral criteria, and there are frequency differences between both sexes (χ 2 = 15.185; p< .001). In B criterion, with regard to BMI-Drive for thinness, women have a higher percentage (36.4%) of compliance with men (19.9%), with significant differences (χ 2 = 17.402; p< .001). In terms of BMI-Bulimia, the percentage of compliance with the criterion is higher in men (28.6%) than in women (21.9%), although there are no significant differences (χ 2 = 3.406; p= .065). The third criterion is based only on behavioral symptoms. It is obtained that 93 women (23.4%) and 56 men (27.2%) fulfill this criterion, there being no gender differences (χ 2 = 1.065; p= .302).

Up to 58.5% of women and 49.5% of men meet the referral criteria (Table 2).

Next, the analyzes carried out on women and men are presented separately, taking into account whether they should be referred to a specialist or not, and depending on the number of criteria met.

Women differences

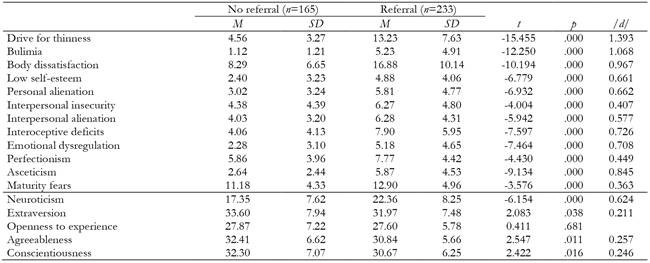

Depending on whether they comply with the referral recommendation, a means test is performed to check the differences between groups. Table 3 shows that in practically all scales and factors there are statistically significant differences.

From effect size the differences in drive for thinness (d= 1.393), bulimia (d = 1.068), body dissatisfaction ( d= 0.967) and asceticism (d = 0.845) stand out. Likewise, effect magnitude is moderate in low self-esteem, personal alienation, interpersonal insecurity, interpersonal alienation, interoceptive deficits, emotional dysregulation and perfectionism scales, and neuroticism factor. Effect size is small in maturity fears, extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness. In each and every one of the scales and factors indicated, it is the women in referral group who register the highest averages.

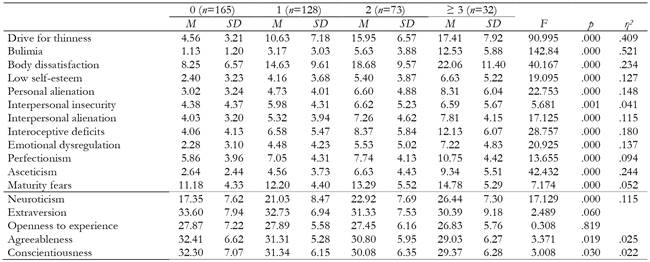

Next, means of scales and factors are compared depending on the number of criteria fulfilled. An analysis of variance is performed, and in order to perform a better analysis, the groups of 3 and 4 criteria met were grouped into one (Table 4). There are statistically significant differences in all the psychological scales of EDI-3, and in the factors of NEO-FFI, neuroticism, agreeableness and conscientiousness. Due to the magnitude of effect size stand out the differences in drive for thinness (η 2 = .409), bulimia (η 2 = .521), body dissatisfaction (η 2 = .234), personal alienation (η 2 = .148), interoceptive deficits (η 2 = .180), emotional dysregulation (η 2 = .137) and asceticism (η 2 = .244). The size of the effect is of moderate magnitude in low self-esteem, interpersonal alienation, perfectionism and neuroticism. In the remaining scales and factors, despite showing statistical significance, the variability attributable to the differences is small.

Men differences

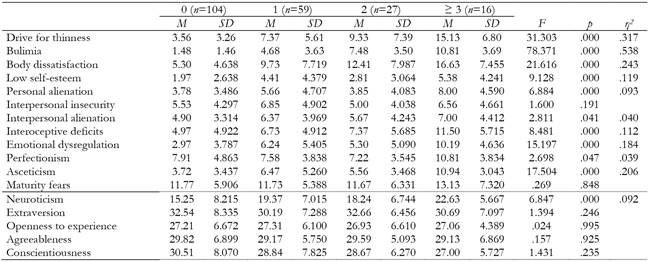

In contrast to the differences found in women, men present differences in fewer scales and factors, as shown in Table 5. Due to magnitude of effect size, highlight the differences in drive for thinness (d = 1.049), bulimia (d = 1.593), and body dissatisfaction (d = 0.945). The differences in low self-esteem, personal alienation, interpersonal alienation, interoceptive deficits, emotional dysregulation, asceticism and neuroticism are also evident. As in women, men who meet the criteria for referral have higher scores on those scales.

As in women, also in men the differences are examined according to the number of criteria met. It can be seen in Table 6 how the greatest differences are found in drive for thinness (η 2 = .317), bulimia (η 2 = .538) and body dissatisfaction (η 2 = .243), emotional dysregulation (η 2 = .184) and asceticism (η 2 = .206). In addition, effect size is moderate in low self-esteem, personal alienation, interoceptive deficits and neuroticism.

Discussion and conclusions

The aim of the study was to compare the differences in personality and psychological variables related to eating disorders, based on compliance with specific criteria that recommend referral to a specialist in ED.

The results found show very high and significant numbers, 58.5% of women and 49.5% of men, who meet referral criteria, and who therefore can be considered as at risk of ED developing. In addition, in comparison with people who do not manifest them, they present high levels of neuroticism, in the basic risk scales, drive for thinness, bulimia, body dissatisfaction, and the related psychological scales.

Attending to the personality, the trait in both women and men that shows a greater effect is neuroticism, with higher scores for those people who meet the referral criteria. Different studies have confirmed the important role of neuroticism in ED, being considered one of the most consistent findings in the literature, since there are clear differences between women and men with and without ED, and in people with higher risk (Claes et al., 2013; García-Palacios et al., 2004; MacLaren & Best, 2009; Podar et al., 2007). In addition, Bulik et al. (2006) and Lilenfeld et al. (2006) affirm the possibility that neuroticism constitutes in itself a risk factor for ED development, and that it has a decisive role in the appearance, expression and maintenance of this disorders (Cassin & von Ranson, 2005). Neuroticism is a personality trait closely related to negative affectivity, and is characterized by facets such as anxiety, hostility, depression, self-consciousness, impulsivity, or vulnerability. Traditionally it has been assumed that people high in this factor suffer frequent mood swings and harbor a tendency to emotional hypersensitivity, finding it difficult to return to normal after intense emotional experiences (Costa & McCrae, 1992). It may be understandable to think that people with high neuroticism are at greater ED risk, and that it is a determining factor in the maintenance of the disorder, in this case due to their constant concern for the weight or shape of their body, for food and its quantity. In fact, figures have been provided, depending on the specific study, between 27 and 61% of patients with different types of ED in which highly obsessive characteristics are present (Vitousek & Manke, 1994).

However, despite the differences found in women in personality traits of extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness, the small magnitude of the effect size does not allow to affirm a clear role of the same, as it has been evident in previous studies in the that ED patients or people with higher risk obtained lower scores in extraversion (García-Palacios et al., 2004; Podar et al., 2007), agreeableness (García-Palacios et al., 2004; Ghaderi & Scott, 2000) and conscientiousness (Ghaderi & Scott, 2000).

Regarding the rest of the psychological variables analyzed, the differences found in both sexes in several scales that the previous literature affirmed as fundamental in ED, especially in the risk index drive for thinness, bulimia and body dissatisfaction, presenting a large effect size. Drive for thinness implies the desire to be thinner, worries about food and weight, and the fear of getting fat. It is a central element associated with the initiation and maintenance of ED symptoms in clinical samples, and high scores in it are an important risk factor for the development of symptoms in non-clinical samples (Garner, 2004). Bulimia in EDI-3 is conceptualized as the tendency to suffer from binge eating or uncontrolled attacks of food intake, and to think about them, in most cases as a response to unpleasant emotional states (Elosua et al., 2010). Regarding body dissatisfaction, it expresses discontent with the shape of the body and the size of certain parts of it, and is one of the fundamental predisposing factors for the ED development, as well as a diagnostic criterion and an important maintenance factor. These three scales in the instrument used contribute to the overall risk index of ED, or reflect the level of concern about diet and weight.

Both drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction are closely linked to disorders linked to the current corporal aesthetic model (Cruz & Maganto, 2002), and there is a multitude of evidence that negative current bodily and aesthetic models have led to overvaluation of thinness and stigmatization of high weight (Bully, Elosua, & López-Jáuregui, 2012; Sámano et al., 2012). As in the present, previous studies with university students find that those women and men who affirm their need to lose weight, although it is in a normal range, have greater body dissatisfaction, discontent with the shape of their body and concerns about diets and the fear of fattening (Berengüí, Castejón, & Torregrosa, 2016, Castejón, Berengüí, & Garcés de Los Fayos, 2016). Also, body dissatisfaction has been related to the BMI (Unikel, Saucedo-Molina, Villatoro, & Fleiz, 2002), finding that more than 60% of university students perceive themselves in a wrong way, overestimating their BMI, and that more than half of the students have a distorted evaluation of their BMI, with males showing a more real body perception, while women tend to overestimate their BMI (Saucedo, Cortés, Villalón, Irecta, & Hernández, 2015).

Along with dissatisfaction, among all the psychological variables studied in relation to ED over decades, perhaps the one that has generated the greatest interest is low self-esteem. Low self-esteem is shown as an important predictor of the ED risk in both sexes (Castejón, 2017), and a close and firm relationship of low self-esteem with body dissatisfaction (Rutsztein et al., 2014) and low physical self-concept (Sánchez, 2013) has usually been proposed. Different studies have also pointed out that low self-esteem is related to fear of negative evaluation of others (Connors & Johnson, 1987), social acceptance (Stice, Schupakneuberg, Shaw, & Stein, 1994), a negative attitude to the expression of emotions and tendency to social comparison in ED patients (Arcelus, Haslam, Farrow, & Meyer, 2013). Also, and related to the present study, the individuals with the highest number of risk behaviors also show an increased ED risk and low self-esteem (Berengüí et al., 2016).

Another scale that provides relevant data in this study is asceticism. It is conceptualized as a tendency to seek virtue through the exercise of ideals such as self-discipline, renunciation, restrictions, self-sacrifice and control of bodily needs, and perfectionism, or the self-imposition of high levels of personal achievement and demanding objectives (Elosua et al. al., 2010; Rutsztein et al., 2014). Of the previous studies that have analyzed this scale, it is found that overweight people with respect to those of low weight, from their BMI, register significantly higher scores of asceticism (Castejón et al., 2016), and higher asceticism scores in people with greater body dissatisfaction (Berengüí et al., 2016). In addition, a study shows how asceticism is the scale that in university students predicts the greatest ED risk, both in women and men (Castejón, 2017). For all these data it is logical to think that people with greater risk of ED, in their distance from the body image they consider ideal and their dissatisfaction, these levels of asceticism cause self-imposed strong food restrictions, and follow a strict discipline to control his desire to eat.

The study also found differences in interoceptive deficits. This scale involves difficulties in recognizing emotions, discomfort when they are intense or out of control, as well as problems in responding to different emotional states. Individuals with high scores experience great discomfort with intense emotions and their distrust of affective and corporal functioning, and it was already described by Bruch (1962) as a central element to understand ED. Regarding emotional maladjustment, it is related to emotionally unstable, impulsive and unreflective people, tending to recklessness, anger and self-destruction (Garner, 2004), and that sometimes has been linked to problems of drug and alcohol abuse. This instability in addition to that powerful emotional discomfort and ineffective control of impulses can be triggers of deficient eating behaviors, and also be a great inconvenience in people already diagnosed. As for personal alienation, it implies feelings of emotional emptiness, loneliness and incomprehension. Interoceptive deficits and emotional dysregulation involve the emotional sphere of the subject, and together in the EDI-3 they make up the affective problems index. In addition, the two scales together with alienation have higher scores in students with greater body dissatisfaction and higher ED risk (Berengüí et al., 2016). For all these results, with high scores in the subjects of higher risk, we can appreciate the fundamental role of the affective aspects. Along with cognitive factors, emotional problems have traditionally been pointed to in the origin of ED in most cases, besides playing a transcendental role in their development (Pascual, Etxebarria, & Cruz, 2011, Quinton & Wagner, 2005).

An important aspect in this study is the existence of differences in interpersonal insecurity and in perfectionism, but only among women. Interpersonal insecurity translates into discomfort in social relationships, and in expressing intimate thoughts and feelings to other people. From the results it can be inferred that women who meet remission criteria may have a tendency to social isolation. On the other hand, perfectionism is one of the classic variables in ED study, having obtained various tests of its effect both in the risk of suffering them, as well as being one of the personality characteristics of ED patients, and a maintenance factor of the AN and the BN (Borda et al., 2011). Perfectionism involves personal self-imposed to achieve high levels of personal achievement and achieve objectives through a maximum exigency level (Garner, 2004). High scores may reflect an extreme need to improve, achieve valuable and ambitious goals, at the same time that does not disappoint the expectations of their parents, teachers or other significant people. It also highlights that extremely high scores may be indicative of psychopathology. The relationship of perfectionism with a higher risk of later ED development has been confirmed (López & Treasure, 2011; Pamies & Quiles, 2014). Likewise, high levels of perfectionism have been affirmed in the development of bulimic symptomatology when combined with the perception of being overweight (Vohs et al., 2001), that along with perceived weight and self-esteem, can prospectively predict the development of bulimic symptoms in young women (Bardone-Cone, Abramson, Vohs, Heatherton, & Joiner, 2006), and that socially prescribed and self-oriented perfectionism is significantly associated with attitudes and behaviors compatible with ED, mainly restrictive, categorizing as a mediator and moderator of the relationship between body image and ED (Behar, Gramegna, & Arancibia, 2014; Pamies & Quiles, 2014). In addition, in studies on personality profiles of the different ED, perfectionism appears in the profile of anorexia, bulimia and binge eating disorder (Cassin & von Ranson, 2005).

We should point out that the study did not pursue the diagnosis of disorders, but offers important figures on the number of subjects at risk of suffering from them. The results clearly indicate the magnitude of the problem, more than half of women and about 50% of men who meet the criteria that place them at risk of ED. The data indicate a large number of subjects that present a depreciated and negative personal self-assessment, low self-esteem, along with instability and difficulty in managing emotions, impulsivity, or ineffective control of impulses, along with practices aimed at maintaining discipline and sacrifice in relationship to fooding, with restrictions and risky behavior. Since they are characteristics that place them at high risk to develop ED, they should be referred to specialists who can delve into these symptoms, and at the same time detect those individuals who may be suffering from disorders. We must also take into account a very important aspect, that is, the population analyzed. In their totality they are students who take degrees belonging to the field of Education, of special sensitivity for their future work with children and adolescents, and in which they also tend to have a high incidence certain problems, such as suffering from the burnout syndrome.

The results obtained should serve as an alarm signal and play an important role in the search for solutions to this problem, as well as in articulating measures that can help in ED prevention, developing programs for the promotion of mental health, to work on the risk variables in this population, for the strengthening of personal and social adaptation behaviors, and for the promotion of an adequate self-concept and self-esteem.

Therefore, more studies of this type are necessary, involving students of other degrees to check and compare the risk in different populations, to delve into the fundamental variables in ED, and at the same time allow the analysis of symptoms and the early detection of disorders.

texto en

texto en