Introduction

Globalization, the advance of technology and market deregulation led to substantial changes in working conditions, increasing the quality and productivity requirements and, consequently, the time pressure and work overload (Schaufeli, Leiter, & Maslach, 2009). At the same time, the introduction of new technologies makes it possible to continue working outside of regular working hours (Shimazu, Sonnentag, Kubota, & Kawakami, 2012) increasing stress and risks to physical and mental health.

Several studies carried out on Argentine workers show the existence of problems and symptoms that deteriorate mental health and quality of life, for example, chronic fatigue, symptoms of anxiety, tension, emotional distress, feelings of inefficiency and low personal fulfillment, among others (Castellano, Muñoz-Navarro, Toledo, Spontón, & Medrano, 2019; Medrano & Trógolo, 2018, Maffei, Spontón, Spontón, Castellano, & Medrano, 2012). Although there are undoubtedly contextual factors that help explain these results; work-related health problems represent a transnational and transcultural problem (Bakker & Demerouti, 2013; Carod-Artal & Vázquez-Cabrera, 2012). For this reason, in recent years, researchers from different latitudes started to show interest in the processes of recovery from work-related fatigue and stress, which occur during leisure time, as well as its effects on health, wellbeing and performance at work (Fritz, Yankelevic, Zarubin, & Barger, 2010; Moreno-Jiménez & Gálvez-Herrer, 2013, Sonnentag & Schiffner, 2019).

Specifically, recovery has been defined as a psycho-physiological relaxation process that occurs after exposure to a stressful situation that requires effort (Geurts & Sonnentag, 2006). This process is conceived as the opposite of stress (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). In this way, while demanding or stressful situations produce a state of psycho-physiological activation of the body, the recovery reduces the activation levels caused by stressful situations, avoiding the accumulation of tension and fatigue and promoting the restoration of resources and energy of the individual (Sonnentag & Geurts, 2009). As a result, there is a feeling of renewal that increases the chances of successfully facing new labor demands (Colombo & Cifre Gallego, 2012).

According to Geurts and Sonnentag (2006), recovery processes can occur in the work context -by means of formal or informal breaks- or outside of it. The former case corresponds to the internal recovery, while the latter is called external recovery and corresponds to the recovery taking place during leisure time. The studies in this latter perspective indicate that although an extended period of rest favors recovery, its effects quickly disappear when returning to work (De Bloom, Geurts, & Kompier, 2013; Syrek, Weigelt, Kühnel, & Bloom, 2018). On the contrary, the processes of daily recovery at the end of the workday or during non-work days have shown a greater impact on the wellbeing of the workers (Garrosa, Carmona-Cobo, Moreno-Jiménez, & Sanz-Vergel, 2015; Geurts & Sonnentag, 2006; Sonnentag, 2001).

There are many activities that can facilitate recovery, such as physical exercise, social activities, practicing hobbies, listening to music or watching television (de Vries, van Hoff, Geurts, & Kompier, 2018; Demerouti, Bakker, Geurts & Taris, 2009, Sonnentag & Zijlstra, 2006). However, it has been pointed out that it is not the activity itself that helps people feel recovered, but the psychological experience that underlies that activity, such as the feeling of relaxation or disconnection (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Thus, reading a book or climbing a mountain are activities that can have the same repairing effect on different people, because the psychological process is similar (e.g., disconnection).

Along these lines, starting from the effort-recovery model (E-R; Meijman & Mulder, 1998), the theory of conservation of resources (COR, Hobfoll, 1998) and the research on the strategies of mood regulation (Parkinson’s & Totterdell, 1999), Sonnentag and Fritz (2007) distinguished between four psychological processes or “recovery experiences:” (a) psychological detachment from work, (b) relaxation, (c) mastery experience and (d) control over leisure time.

The psychological detachment refers to the disconnection from work in physical and mental terms (Etzion, Eden, & Lapidot, 1998); it implies not only being absent from the workplace, but not thinking about it or doing work-related activities outside of it (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Relaxation is characterized by a state of low activation, associated with pleasant feelings (Hahn, Binnewies, Sonnentag, & Mojza, 2011) resulting from various activities such as meditating, watching a movie or listening to music (Sonnentag & Geurts, 2009). Therefore, it is associated with activities that don’t require effort. On the other hand, the mastery experience constitutes activities that imply a greater effort for the individual. These types of experiences include those that offer the opportunity to face challenges, learn new things or expand horizons (e.g., learn a new hobby, practice an extreme sport). Although these kinds of activities involve an expenditure of energy, allow the generation of new personal resources (e.g., development of new skills, sense of self-efficacy) and favor positive moods that facilitate recovery (Sonnentag & Geurts, 2009; Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Finally, the control over leisure time refers to the ability of the individual to decide what activity to perform during his leisure time, when and how to do it. The perception of control not only reduces anxiety, but also acts as an external resource that facilitates the development of activities that promote recovery.

Based on the guidelines outlined above and without counting on assessment tools Sonnentag and Fritz (2007) developed the Recovery Experience Questionnaire (REQ), a 16-item tool created with the aim of assessing the four recovery experiences. The confirmatory factorial analyses in two independent samples confirmed the distinction between the four recovery experiences. Satisfactory internal consistency indices were also obtained for the four dimensions (Cronbachs α values between .79 and .85) as well as evidence of external validity with different individual (depression, somatic symptoms, burnout, insomnia, life satisfaction) and organizational variables (time pressure, role ambiguity, overtime). Subsequent studies with samples of workers from Spain (Sanz-Vergel et al., 2010), Sweden (Almén, Lundberg, Sundin, & Jansson, 2018), Japan (Shimazu et al., 2012), South Korea (Park, Park , Kim, & Hur, 2011), South Africa (Mostert & Els, 2015), Finland (Kinnunen, Feldt, Siltaloppi, & Sonnentag, 2011) and Holland (Bakker, Sanz-Vergel, Rodríguez-Muñoz, & Oerlemans, 2015) corroborated the factorial structure of the scale and showed good reliability indices for all dimensions, as well as theoretically expected correlations with different variables of interest, ratifying the psychometric quality of the REQ.

In this paper, the reliability and validity of REQ scores in Argentine workers is analyzed for the first time. It is, thus, expected to respond to a demand both scientific and professional, since there are no adapted instruments that allow the assessment of recovery experiences in workers. Based on this, the following objectives were set: (a) analyze the factorial structure of the REQ, (b) examine the internal consistency and reliability of construct of each scale and (c) provide evidence of validity of construct (studies of internal convergent and discriminant validity), and (d) provide external evidences of validity (test-criterion) analyzing their relationship with measures of positive affect, negative affect, burnout and work engagement.

The recovery benefits have been broadly studied. For example, Sonnentag, Binnewies and Mojza (2008) found that after-work recovery experiences were associated with a more positive affect and a less negative affect the next morning and at the end of the week (Sonnentag, Mojza, Binnewies & Scholl, 2008). On the other hand, the recovery experiences are negatively associated with burnout symptoms, particularly with exhaustion (Sonnentag, Kuttler, & Fritz, 2010; Siltaloppi, Kinnunen, & Feldt, 2009), and positively with work engagement (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). However, the findings regarding engagement have not been consistent (Shimazu et al., 2012; Wendschen & Lohmann-Haislah, 2017). In fact, Shimazu et al. (2016) suggest a curvilinear relationship (in the form of an inverted U) with the engagement, so that very low and very high levels of disconnection had negative effects on engagement, while moderate levels of disconnection were associated with high levels of engagement.

Method

Participants

A non-probabilistic sample was used, consisting of 505 workers from the general population of the city of Cordoba, Argentina. The age range of the participants was from 19 to 69 (M = 31.62; SD = 8.41). 43% of participants were men and the other 57% were women. The sample consisted of public sector employees (36.4%), private (61.6%) and NGOs (2%). The majority had an employment contract for an undetermined period (49%) and had a graduate degree at the time of the study (33.5%). Regarding service time in the company/organization, the average time they had been working was 4.66 years (SD = 5.07), while the average time on the current position was 3.94 years (SD = 5.14).

Tools

Recovery experiences. The Spanish adaptation of the Recovery Experience Questionnaire (Sanz-Vergel et al., 2010) was used. This is a self-reported questionnaire consisting of 4 sub-scales of 4 items each, which evaluate different processes that underlie recovery versus work demands and requirements: psychological detachment (4 items, "When I leave work I forget completely about work"), relaxation (4 items, "After work I take my time to rest"), mastery experience (4 items, "After work I do other activities that pose a challenge for me") and control over leisure time (4 items, “I can decide for myself what activities to do during my free time”). Participants must indicate the degree of agreement or disagreement with each of the situations reflected in the items, using a Likert scale with 5 options, from 1 (Fully disagree) to 5 (Fully agree).

Burnout. Was assessed through the Argentine version (Spontón, Trógolo, Castellano, & Medrano, 2019) of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS; Schaufeli, Leiter, Maslach & Jackson, 1996). The original scale consists of 16 items and three factors corresponding to the theoretical dimensions of burnout proposed by Maslach: exhaustion (5 items), cynicism (5 items) and professional inefficiency (6 items). The studies carried out in Argentina showed that a model composed of the “core” dimensions of burnout (exhaustion and cynicism) presented a better fit than a three factor model that included professional inefficiency as a third component. Therefore, in the present study, the sub-scales of exhaustion and cynicism were applied. The answers to all items are given using a Likert scale with 7 options, from 0 (never) to 6 (always) according to the frequency with which the individual feels in the way described by the item.

Engagement. The Utrech Work Engagement Scale (UWES; Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá, & Bakker, 2002) was applied. The UWES scale is a 17-item questionnaire developed to obtain a measure of the three theoretical dimensions of engagement: vigor (6 items), dedication (6 items) and absorption (5 items). The answers to all items are given using a Likert scale with 7 options, from 0 (never) to 6 (always). In Argentina, evidence was obtained confirming the three-dimensional structure of the scale together with indices of satisfactory internal consistency (α coefficients between .69 and .88) on all dimensions (Spontón, Medrano, Maffei, Spontón & Castellano, 2012).

Affect. Affect is assessed through the Argentine validation (Moriondo, De Palma, Medrano, & Murillo, 2011) of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). The PANAS consists of two sub-scales with 10 items each: positive affect (e.g., “proud,” or “interested”) and negative affect (e.g., “disgusted,” or “guilty”). The participant had to indicate on a 5-position scale (from 1 = very little or at all; to 5 = always or almost always) to which extent he/she felt the way described by the item during the previous two weeks of work. The Argentine version showed good psychometric properties, confirming the internal structure of the original scale and good reliability indices (α = .73 and .82 for the scales of positive affect and negative affect, respectively).

Sociodemographic questionnaire. An ad hoc questionnaire was designed through which information regarding sex, age, job position, sector, to which the organization/company belongs, and education level of the workers, among others, was collected.

Procedure

The items in the Spanish version of the REQ were revised to assess their adequacy to the colloquial speech in Argentina. In essence, even if the language is the same -in this case Spanish- the linguistic and cultural characteristics may differ significantly from one country to another, and it is therefore necessary to review the items to ensure that the language is adequate in its linguistic and cultural aspects for the population (Chahín-Pinzón, 2014). For this purpose, a Spanish language teacher was asked to evaluate the content of the tool, emphasizing the connotative meaning of the items and those idiomatic expressions that could be inapplicable or strange in the Argentine context. No change was needed. Then, the tool was piloted on two groups of workers (n = 7, n = 10) using the focus group technique. The first group belonged to employees of a service company, while the second group corresponded to workers of a healthcare institution. Individuals were asked to complete the questionnaire individually and, subsequently, to verbally paraphrase the items in order to evaluate the meaning and the response process involved. Finally, the content of the item was discussed within the group. There were no comprehension difficulties and the participants reported that it was an interesting and simple tool to answer.

The final administration of the questionnaires was made with people from the research environment and others who were casually hired for the research, as well as in companies, public institutions and non-profit organizations upon authorization from executives and company authorities. The data collection was carried out between March and September 2018; the administration of the questionnaires was carried out in small groups (approximately 10 people) at the workplace and was carried out by the authors of the research, who gave the instructions and all the necessary information related to the research. In all cases, the written consent was obtained by means of a letter that specified the purpose of the study and in which the voluntary and anonymous aspects of the participation were guaranteed. Finally, a written report was provided with the main results and specific recommendations in order to optimize the recovery levels of the workers, institutions and companies that agreed to participate in the research. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the university where the research project was based.

Data analysis

An initial analysis of the data was carried out to examine the assumptions of linearity, normality and multicollinearity of the items. The factorial structure of the REQ was assessed through a confirmatory factorial analysis (CFA). For the estimation of the model the Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance (WLSMV) was used, for being more appropriate for ordinally scaled items (Li, 2016), while the adjustment was evaluated through different indicators: the chi-square statistic (χ2), the comparative adjustment index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the weighted residual quadratic mean (WRMR). Values above 0.95 for the CFI and TLI indices indicate an optimal adjustment, while values above 0.90 represent an acceptable adjustment. For the RMSEA, values lower than 0.05 are considered optimal and those lower than 0.08 acceptable, and finally for the WRMR values lower than 1.00 are expected (Yu & Muthén, 2002). In addition to the adjustment indices, the internal consistency was estimated among the items of each factor (ordinal alpha), the reliability of construct (degree to which a construct is “captured” by the information contained in its indicators), the average variance extracted (amount of variance of the indicators explained by the latent variable compared to the one captured by the measurement error), the convergent internal validity (degree to which the indicators evaluate the same construct) and the internal discriminant validity (independence of the variables latent to each other and that therefore represent different domains). Finally, the test-criterion validity was analyzed by examining the correlations (Pearson’s r) between the scores corresponding to the scales of the REQ and the scales of burnout, positive affect and negative affect. To test the relationships between the REQ factors and the engagement scales, given that previous evidence suggests non-linear correlations between these variables, curvilinear regressions with the REQ dimensions were estimated as predictors and the engagement scales as criteria, examining both the linear and quadratic fit of each model. All the analyses were carried out using the statistical package SPSS v20.0, except the CFA, which was carried out with the Mplus v6.12 software.

Results

Confirmatory factorial analysis

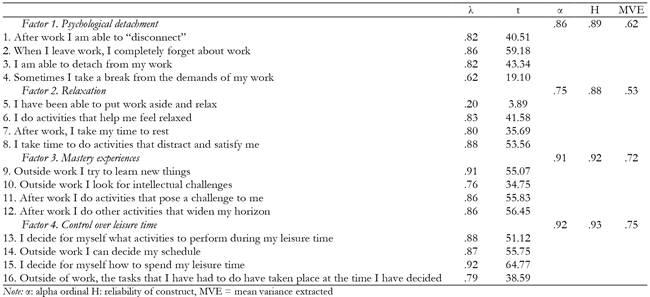

A model composed of four latent variables corresponding to the four recovery experiences was specified. The results showed acceptable adjustment indices in some cases (CFI and TLI) and unacceptable ones in others (RMSEA and WRMR), χ2(98) = 649.97, p < .001, CFI = .95, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .11 (90% IC: .10, .12), WRMR = 1.53. The examination of the adjustment indices revealed that item 5 (“I have been able to put work aside and relax”), corresponding to the relaxation scale, presented high crossed saturations on the psychological detachment scale (= .72). By re-specifying the model allowing the item to saturate on both scales, the adjustment indices improved significantly, χ2(97) = 377.39, p < .001, CFI = .98, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .07 (90% IC: .06, .08), WRMR = .98. All regression coefficients between the latent variables and their indicators were significant (p < .001). The results are presented in Table 1.

The reliability of the REQ was evaluated using the alpha ordinal coefficient (α), the reliability of construct (RC) and the mean variance extracted (MVE). The RC was measured by the H coefficient since it is a robust coefficient to the variations in the magnitude of the saturations between the items of a factor (Domínguez-Lara, 2016). As well as for the α coefficient, values ≥ .70 of the H coefficient are considered satisfactory. Regarding the MVE, values higher than .50 imply that a substantial amount of the variance of the indicators is explained by the construct in comparison with the variance attributed to the measurement error (Arias, 2008). As observed in Table 1, all the REQ dimensions reach values higher than the recommended ones.

The convergent internal validity was evaluated by reviewing the t values corresponding to the factorial saturations. If the t values are statistically significant (≥1.96), this constitutes evidence that, indeed, all the indicators assess the same construct (Arias, 2008). As observed in Table 1, all the t values widely exceed the critical value of 1.96

Finally, the internal discriminant validity of the different dimensions of the construct was examined by means of a single-factor FCA model in which all the items were saturated. The evidence in favor of the one-dimensional model would indicate that the latent variables do not demonstrate discriminant validity, that is, that they do not measure different domains (Furr, 2011). The results obtained show that the model does not present a good fit in the data, χ2(104) = 2510.94, p < .001, CFI = .79, TLI = .76, RMSEA = .21 (90% IC: .20, .22), WRMR = 3.84.

Proofs of the test-criteria validity

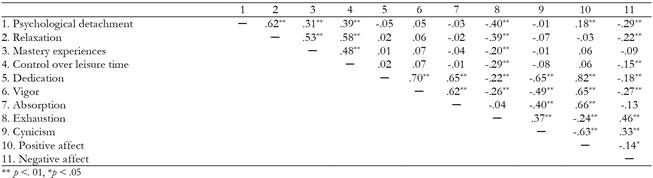

The criterion validity of the REQ was analyzed by relating the four dimensions with different theoretically relevant constructs according to previous studies (Table 2). Based on the background, the hypothesis was that all scales of the REQ would correlate positively and negatively with a positive and negative affect, respectively. The results show theoretically expected correlations between all the dimensions of the REQ and negative affect. On the other hand, except for the dimension of psychological distancing, the other REQ scales did not show significant relationships with positive affect. On the other hand, according to what was expected, negative correlations were obtained between the dimensions of the REQ and the symptoms of exhaustion, while no relationship was observed with the symptoms of cynicism. Finally, linear relationships between the different REQ dimensions and the engagement scales (dedication, vigor and absorption) were not obtained.

Table 2. Correlations between the REQ dimensions and the measurements of work engagement, positive and negative affect.

In order to explore possible curvilinear relationships between recovery experiences and engagement, different regression models were evaluated by introducing the REQ dimensions as predicting variables and the dimensions of engagement as a criterion, estimating the linear fit as a quadratic of each model. As noticed in Table 3, the fit of the quadratic model (in the form of an inverted U) was significant for three dimensions of the REQ (relaxation, mastery experiences and control over free time) and vigor, R 2 = .017, .016 and .019. In this way, recovery experiences (except psychological detachment) are curvilinear related to vigor. On the other hand, neither the linear model nor the quadratic model were significant to explain the relationship between recovery experiences and the other engagement dimensions (dedication and absorption), as shown in Table 3.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze the psychometric properties of the Recovery Experience Questionnaire developed by Sonnentag and Fritz (2007). In line with the original scale and subsequent validations in different countries (e.g., Park et al., 2011; Sanz-Vergel et al., 2010; Shimazu et al., 2012), the CFA results support the existence of four factors consistent with the four experiences of recovery: psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery experience and control over free time. However, it is important to note that the initial model did not present a good fit, and some re-specifications must be introduced. Particularly, the item “I have been able to put work aside and relax” which originally corresponds to the relaxation scale, presented crossed saturations on the psychological detachment scale, having a stronger inclusion in this one. Similar results have been previously reported (Kinnunen et al., 2011; Mostert & Els, 2015), which could indicate a specification problem in the model (Rodriguez-Ayan & Sotelo Rico, 2015). In fact, the adjustment indices suggest that it would be more appropriate to consider the item as an indicator of psychological detachment. However, if the content of the item is taken into account, it is possible to notice that its wording is ambiguous since it includes situations referring to both detachment ("I have been able to put work aside ...") and relaxation ("... and relax myself"), which would explain the cross saturations. Consequently, it would be useful to modify the content of the item, or replace it with a new one.

On the other hand, the reliability analysis showed that all the dimensions of the REQ have an acceptable internal consistency and an adequate reliability of the construct. In this way, it can be concluded that the indicators of each scale, taken together, are a reliable measure of the construct. Additionally, the analysis of the mean variance extracted showed that a significant percentage of the variance of the indicators of each sub-scale is explained by the latent variable. This provides additional confidence in the operationalization of the latent variables. All the REQ scales presented positive correlations between each other, with stronger relationships between psychological detachment and relaxation, on the one hand, and relaxation and control over leisure time, on the other. In this way, although the evidence of internal discriminant validity indicates that these are different experiences, the correlations suggest that the recovery processes are not totally independent but can co-exist to a certain extent (Bakker et al., 2015). For example, watching television can be an activity that not only helps you relax, but also to disconnect from work. In a similar way, having control over free time represents a resource that can help workers plan and organize their free time better, facilitating the development of activities that promote disconnection, relaxation and/or the mastery of experiences.

Correlations with other constructs showed that workers with greater recovery experience less negative affect, in line with other studies (Fritz, Sonnentag, Spector, & McInroe, 2010). On the other hand, no relationships were observed with the positive affect, except for psychological detachment, which contradicts the results of other studies (Sonnentag, Mojza et al., 2008). However, some studies suggest a differential pattern in the relationships between recovery experiences and positive affect. Thus, Sonnentag, Binnewies et al. (2008) found that relaxation was associated only with positive affects of low activation (e.g., feeling quiet and calm), while the mastery of experiences was particularly related to positive affects of high activation (e.g., feeling strong, happy). Given that the PANAS items evaluate a restricted domain of the affective experiences (affects of high activation), it is possible that this limitation in the content of the tool helps explain the absence of relationship between some dimensions of the REQ and the positive affect. Another factor that could have affected the correlations derives from the research design used. In fact, unlike previous studies that use daily measures, in this work, the affective experience was evaluated in a general and retrospective way, being more prone to the influence of retrospective biases caused by the loss of contextual information associated with the emotional event (Robinson & Clore, 2002). Ready, Weinberger and Jones (2007) found that people tended to underestimate positive affective experiences through the use of retrospective reports, as compared to daily self-reports, whereas this was not happening with negative affective experiences. Therefore, it would be useful to replicate the present study through daily research and affective measures that contemplate a greater range of affective experiences (e.g., PANAS-X, Watson & Clark, 1994).

On the other hand, recovery was associated with lower levels of exhaustion. This result is consistent with the previous literature (Fritz & Sonnentag, 2007; Siltaloppi et al., 2009) and shows the importance of carrying out activities that restore the energy and resources invested in the work, thus avoiding the accumulation of fatigue and exhaustion that leads to the health deterioration (Sonnentag & Geurts, 2009). On the other hand, the recovery experiences were positively associated with vigor, in line with different studies that show that workers who recovered after work felt more vigorous the next morning (Sonnentag et al., 2008, Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). However, in the present study, we found a curvilinear U-shaped inverted relationship between these variables, which seems to indicate that moderate levels of recovery (e.g., relaxation) are beneficial, while very high levels can have a negative effect, as well as an insufficient recovery. As Shimazu et al. (2016) indicate since vigor implies an activation component, the “excess” of detachment or relaxation can hinder the mobilization of energy necessary to respond to work demands, generating a deactivation state that prevents “reconnecting” with work. Similarly, dedicating most of free time to hobbies that are exciting or perform very demanding sports can decrease the interest of the individual towards other activities such as work, affecting resources (e.g., energy) that end up having a negative impact on the engagement and performance levels (Sonnentag, Venz, & Carper, 2017). Beyond this, it is noteworthy that recovery experiences accounted for only about 2% of the variance of vigor. This percentage of variance is similar to that obtained in other studies (Shimazu et al., 2016) and reflects a smaller contribution of recovery experiences on engagement. Even so, in the present study, the contribution of each of the recovery experiences was analyzed separately. Bearing in mind that these processes may occur, it would be interesting in future research to analyze the joint influence of recovery experiences on engagement.

In summary, the results obtained in the present work indicate good psychometric properties of the REQ for its use in Argentina. However, taking into account that the sample was largely composed of workers from the private sector, it would be useful to replicate the study with workers from the general population. Likewise, it would be valuable in future research to obtain additional evidence of the properties of the REQ, such as its convergent, predictive and discriminant external validity based on its relationships with other constructs. Finally, although there is evidence to suggest that the desirability bias does not represent a serious problem in the REQ (Mojza, Lorenz, Sonnentag, & Binnewies, 2010), it would be equally valuable to develop new studies to examine this aspect.

Even with these limitations, the results are satisfactory and allow us to have a valid tool for Argentina, which provides useful information at a personal and organizational level by positioning recovery as an important variable in the prevention of psychosocial risks. It also provides scientific evidence to both managers and professionals in the design and implementation of activities focused on the healthcare of employees, as well as training on the use of free time, leisure activities and relaxation techniques (Colombo & Cifre Gallego, 2012). Finally, we hope to develop new research with this tool that allows advancing in the knowledge of recovery experiences of Argentine workers, facilitating the identification of the factors that favor or hinder the processes linked to the recovery from stress.

texto em

texto em