Introduction

Research into child-to-parent violence (CPV) has increased since the year 2000, probably as the result of the exponential growth in prevalence rates (Calvete, Gámez-Guadix, & Garcia-Salvador, 2015; Calvete et al., 2013; Castañeda, Garrido-Fernández, & Lanzarote, 2012; Del Moral Arroyo, Martínez Ferrer, Suárez Relinque, Ávila Guerrero, & Vera Jiménez, 2015; Eckstein, 2004; Ibabe, 2014, 2015; Izaguirre & Calvete, 2017; Kennedy, Edmonds, Dann, & Burnett, 2010; Miles & Condry, 2016; Morán Rodríguez, González-Álvarez, Gesteira, & García-Vera, 2012; Pagani et al., 2004), parents’ increasing demands for help controlling their children (Strom, Warner, Tichavsky, & Zahn, 2014) and the emergence of widespread social rejection of any kind of intrafamily violence (Agustina & Romero, 2013).

The hardest challenge has been to establish a consensus regarding a comprehensive definition of what CPV actually is (Coogan, 2014; Morán Rodríguez et al., 2012). Indeed, some authors have suggested that the heterogeneity of the results may in fact be due to different definition and measurement criteria and/or different understandings of the problem that have guided the responses given by professionals, researchers and public policies (Coogan, 2011; Holt, 2016).

Recently, experts from the Spanish Society for the Study of Child-to-Parent Violence (SEVIFIP - Sociedad Española para el Estudio de la Violencia Filio-Parental) agreed on the following definition:

Repeated acts of physical, psychological (verbal or non-verbal) or economic violence by children against their parents or parental figures. The following behaviors are not considered child-to-parent violence: one-off acts of aggression, those perpetrated during a diminished state of awareness that are not repeated once said awareness is recovered (alcohol intoxication, withdrawal syndromes, delirium or hallucination), those caused by (transitory or permanent) psychological disorders (autism or severe mental disability) and parricide with no prior history of aggression (Pereira et al., 2017, p. 6).

Instrumental or reactive aims are also excluded, due to the difficulty of distinguishing them when they become a habitual characteristic of the interaction. Other authors, however, highlight the fact that one of the defining traits of CPV is a child’s desire to gain control over their parents (Aroca-Montolío, Lorenzo-Moledo, & Miró-Pérez, 2014; Cottrell, 2003; Hong, Kral, Espelage, & Allen-Meares, 2012; Molla-Esparza & Aroca-Montolío, 2017; Paterson, Luntz, Perlesz, & Cotton, 2002; Tew & Nixon, 2010). This approach identifies parents and adolescents as victims and perpetrators, respectively.

As regards prevalence, longitudinal studies with community samples of adolescents and parents in the US and Canada report that physical CPV affects between 11% and 22% of the population, while psychological CPV affects between 51% and 75% (Margolin & Baucom, 2014; Pagani, Larocque, Vitaro, & Tremblay, 2003; Pagani et al., 2009, 2004). In Spain, studies with similar designs establish prevalence rates at between 7.8% and 8.4% for physical CPV and between 91.2% and 95.8% for psychological CPV, as reported by adolescents; however, when informants were parents, these figures were between 8.3% and 13.8% for physical CPV and between 85% and 99.4% for psychological CPV (Calvete, Gámez-Guadix, et al., 2015; Calvete, Ibabe, Gámez-Guadix, & Bushman, 2015). Economic CPV is estimated at between 29.8% and 59% in terms of damage to property (Condry & Miles, 2014; Margolin & Baucom, 2014) and at 15.8% in terms of theft (Condry & Miles, 2014).

Nevertheless, these figures should be interpreted cautiously, due to the fact that many parents hide the true extent of the abuse they suffer due to fear, the stigma attached to being a victim or even a desire to maintain the myth of “family harmony” (Agnew & Huguley, 1989; Brule & Eckstein, 2016; Calvete, Gámez-Guadix, & Orue, 2014; Calvete, Orue, & Gámez-Guadix, 2012; Carrasco García, 2014; Claver Turiégano, 2017; Contreras & Cano, 2014b; Cottrell & Monk, 2004; Eckstein, 2004; Edenborough, Jackson, Mannix, & Wilkes, 2008; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2011; Kennedy et al., 2010; Kuay et al., 2016; Laurent & Derry, 1999; Murphy-Edwards & van Heugten, 2018; Pagani et al., 2003; Pérez & Pereira, 2006; Tew & Nixon, 2010; Walsh & Krienert, 2007; Wilcox, 2012; Williams, Tuffin, & Niland, 2017).

Indeed, although the 2017 Annual Report issued by the Spanish Public Prosecutor’s Office referenced the lowest number of cases this decade (the figure dropped from 4,898 cases in 2015 to 4,355 in 2016) (Fiscalía General del Estado, 2017, p. 593), it also pointed out that in that same year (2016), 9,496 cases were shelved and could not be pursued because the presumed perpetrators were under 14 years of age. Although the report failed to specify what percentage of these shelved cases corresponded to CPV, the data nevertheless suggest an increasing number of hidden cases.

The risk and protection factors identified were both varied and fairly non-specific (Hong et al., 2012; Kennair & Mellor, 2007; Morán Rodríguez et al., 2012), being linked to domestic violence (Holt, 2016; Miles & Condry, 2015, 2016; Wilcox, 2012) or social learning theory (Aroca-Montolío, Bellver Moreno, & Alba Robles, 2012), and although some theoretical hypotheses are confirmed by certain results, none are able to explain all the findings reported.

According to some recent reviews (Hong et al., 2012; Simmons, McEwan, Purcell, & Ogloff, 2018), the ecological theory may constitute an integrative framework. However, a systematic analysis is required in order to enable the phenomenon to be observed as a relational circuit, rather than as a set of individual actions.

The scoping review presented in this paper was carried out with the aim of shedding some light on the study of this phenomenon (Anderson, Allen, Peckham, & Goodwin, 2008), since the methodology used enables an exhaustive map of the principal sources of information to be compiled and theoretical explanations and new avenues of research to be identified (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Joanna Briggs Institute, 2015; Levac, Colquhoun, & O’Brien, 2010). The aims were as follows: 1. To identify existing studies, analyzing them in accordance with design, sample characteristics and theoretical framework; 2. To describe the explanatory factors referenced; and 3. To identify future avenues of research.

Method

To carry out the scoping review, we followed the five stages described by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), the recommendations made by other authors in relation to this method (Daudt, Van Mossel, & Scott, 2013; Levac et al., 2010), and the Prisma criteria (Moher et al., 2015).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Empirical studies focusing on the general population, the clinical population and those who have reported/been accused of CPV within the judicial system were accepted for the review. All had been peer reviewed, had been published in either Spanish or English between 2000 and 2017 and included one of the following types of samples: (a) adolescents (10-19 years) of either sex who had perpetrated CPV; or (b) parents of either sex and any age who had been victims of CPV. Case studies, expert opinions and therapeutic experiences were excluded from the review. Since all the data were taken from published studies, no ethical approval was required.

Search strategies

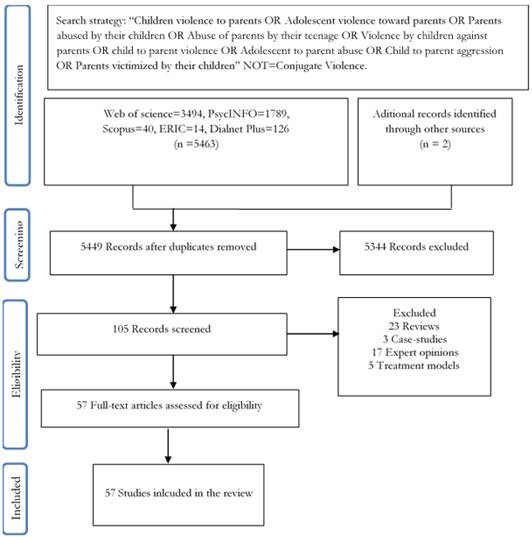

The search was conducted between October 2017 and April 2018. To guarantee a good level of sensitivity, the descriptors (Figure 1) were established in accordance with the research aims. The following databases were consulted: Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO, ERIC and Dialnet Plus, and the Boolean operators “OR” and “NOT” helped restrict the parameters of the search.

Study selection

The studies returned by the search were screened first by the lead author, who read the abstracts and determined whether or not they complied with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The Mendeley manager was used to enter the studies sequentially, save them and eliminate duplicates.

The eligibility of the studies that passed the first screening process was determined during a second phase, in which both authors read the entire texts. In the event of discrepancies regarding whether or not a particular paper should be included, an effort was made to reach a consensus.

Assessing the risk of bias

To minimize the risk of bias (Manterola & Otzen, 2015), all the studies included in the review were checked to determine whether or not they complied with the following set of minimum requirements: they used appropriate sampling methods; they complied with the established inclusion and exclusion criteria; they used clear operational definitions of CPV; they used qualitative data gathering instruments and/or techniques; they used quantitative or qualitative result analysis methods; and the level of missing data was not high enough to affect the results.

Data gathering process

To extract the data, a form was developed containing the following areas: sociodemographic information (age, marital status, socioeconomic status, education, country, prevalence, type of CPV), methodological information (sample, aim, data analysis) and theoretical and explanatory data (individual and family factors). These variables were chosen on the basis of an initial trial analysis which revealed that not only did they enable the extraction of information that was relevant to the study aims, they could also be applied to all the studies included in the review, even those with different designs (Levac et al., 2010).

Analysis of the results

Separate analyses were carried out of the study characteristics (design, sample, origin, type of CPV), theoretical frameworks and explanatory factors. The Nested Ecological Theory was used to classify the explanatory factors of CPV. This theory establishes the microsystem, exosystem and macrosystem levels, as well as the ontogenetic level, which is continually influenced by the other three (Cottrell & Monk, 2004).

Results

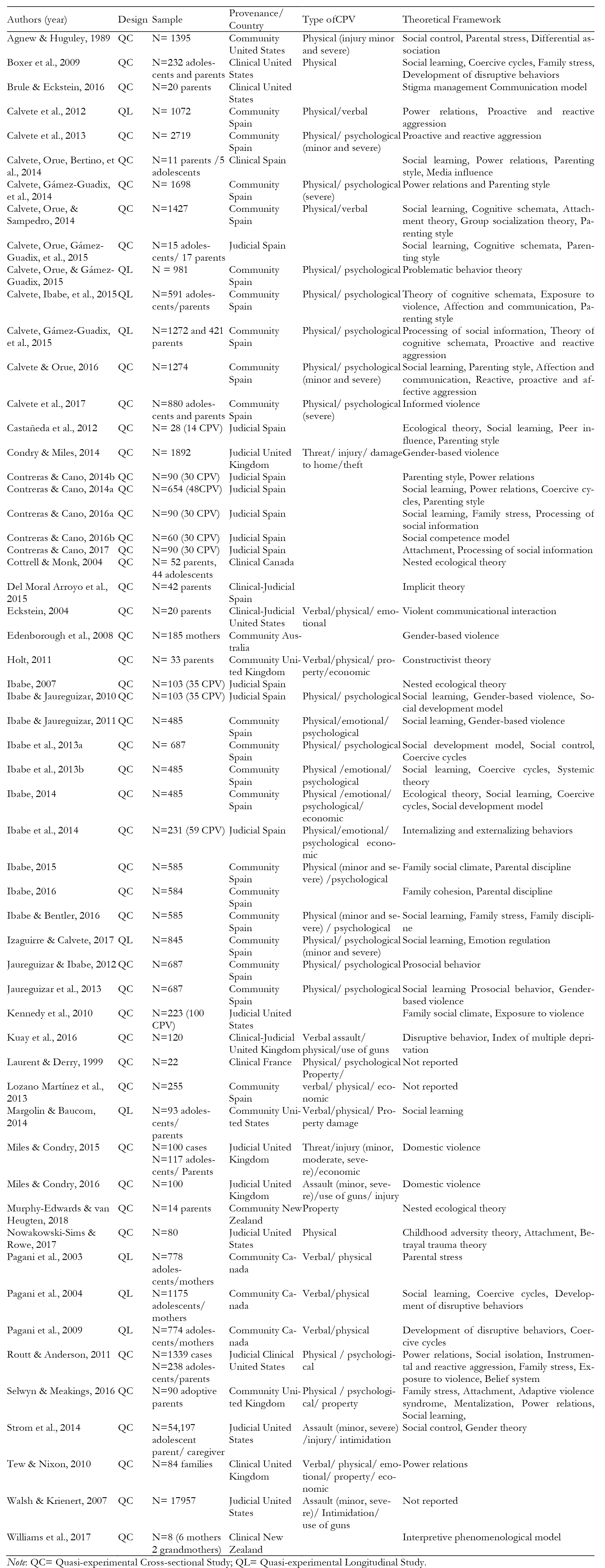

Distribution of the publications in accordance with design

Following the classification system proposed by Ato, López and Benavente (2013), the designs used in the 57 papers included in the review were analyzed in accordance with their manipulation strategy. All the studies had quasi-experimental designs, with 48 being cross-sectional in nature and 9 being longitudinal (Table 1). Thus, overall, most of the papers reviewed presented cross-sectional quasi-experimental studies, the majority of which were conducted in Spain (n=27). The few longitudinal quasi-experimental studies identified were carried out in Spain, (n=5), Canada (n=3) and the US (n=1).

Distribution of publications in accordance with sample characteristics, year, origin and type of CPV

Of the publications analyzed, 7 focused on the clinical population, 17 on those involved in cases brought to the attention of the judicial system, 29 on the general population and 4 on a combined clinical and judicial context.

The most representative in terms of sample size were 2 studies carried out in the US which included over 10,000 criminal cases (Strom et al., 2014; Walsh & Krienert, 2007) and 8 community-based studies covering over 1,000 cases (Agnew & Huguley, 1989; Calvete, Gámez-Guadix, et al., 2015, 2014; Calvete et al., 2013, 2012; Calvete & Orue, 2016; Calvete, Orue, & Sampedro, 2014; Pagani et al., 2004).

It is interesting to note that 26.3% of the studies (n =15) gathered and analyzed information from both adolescents and parents; four studies identified abuse towards siblings (Brule & Eckstein, 2016; Castañeda et al., 2012; Laurent & Derry, 1999; Routt & Anderson, 2011) and only one was carried out with adoptive families (Selwyn & Meakings, 2016).

Also, 63% of the studies were carried out between 2013 and 2017 and 56% were carried out in Spain, 18% in the US, 12% in the UK and 7% in Canada. No studies conducted in Latin America were found.

As regards the type of CPV analyzed, 30% reported data on physical and psychological abuse, 19% on physical and verbal abuse, 9% on threats and injuries, 7% on physical, emotional and psychological abuse and 5% on physical abuse alone. Few authors analyzed economic abuse (Condry & Miles, 2014; Holt, 2011; Ibabe, 2014; Ibabe, Arnoso, & Elgorriaga, 2014; Lozano Martínez, Estévez, & Carballo Crespo, 2013; Margolin & Baucom, 2014; Miles & Condry, 2015; Tew & Nixon, 2010), property damage (Condry & Miles, 2014; Holt, 2011; Laurent & Derry, 1999; Margolin & Baucom, 2014; Murphy-Edwards & van Heugten, 2018; Selwyn & Meakings, 2016; Tew & Nixon, 2010) and the use of weapons (Kuay et al., 2016; Miles & Condry, 2016; Walsh & Krienert, 2007). Finally, 28% (n =16) of the papers failed to specify the type of CPV studied.

Theoretical framework

The majority of the studies explained CPV in terms of psychological theories:

Cognitive-behavioral: Social Learning, Coercive Cycles, Social Information Processing, Cognitive Schemata, Prosocial Behavior, Implicit Theory, Development of Disruptive Behaviors, Adaptation to Violence Syndrome;

Psychodynamic: Attachment Theory, Childhood Adversity Theory, Betrayal Trauma Theory, Mentalization Theory; and

Psychosocial: Group Socialization Theory; Power Relations Theory; Social Competence Model.

Theories from other fields were also referenced, including: Communications (Stigma Management Communications model); Criminology (Social Control, Differential Association, Social Development Model); Sociology (Gender Violence, Domestic Violence) and broader integrative models such as Phenomenological and Constructivist Ecosystems Theory.

Some authors proposed specific constructs such as: internalizing and externalizing problems (Ibabe et al., 2014), parental stress (Pagani et al., 2003), communication (Eckstein, 2004), family climate (Ibabe, 2015; Kennedy et al., 2010), parental discipline (Ibabe, 2015, 2016) and exposure to violence (Kennedy et al., 2010).

Explanatory factors

Table 2 presents a summary of the explanatory factors identified, structured into ecological levels in accordance with Cottrell and Monk's theory (2004). In the macrosystem, the factors found were: work-life balance difficulties, particularly among single parent families, justification of and belief in the low level of punishment for violence and the influence of the media and stereotypes.

The factors identified in the exosystem were: violent intergenerational transfer, violent peer relationships, problems at school, concurrence of other forms of violence, impulsive conflict resolution style and poor social adaptation. A positive atmosphere in class was identified as a protective factor at this level.

The factors identified in the microsystem were: direct violence, low levels of family cohesion, difficult communications and a lack of appropriate disciplinary styles. Clinical symptoms and drug abuse among parents further complicated the situation. Prosocial behaviors and a positive family environment were identified as protective factors at this level.

At the ontogenetic level, the studies highlighted history of childhood aggression, clinical symptoms, low levels of social sensitivity and emotion regulation and drug and alcohol abuse.

Discussion

The review aimed to identify the explanatory factors and theoretical frameworks of CPV, as well as future research areas. The results reveal that this is not a new phenomenon (Ibabe, 2007; Simmons et al., 2018), but rather one that has only recently become more visible, why is probably why the majority of studies had cross-sectional quasi-experimental designs. Consequently, there is a need for longitudinal data and experimental studies (Calvete, Orue, Gámez-Guadix, et al., 2015; Calvete et al., 2017; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2011; Simmons et al., 2018).

Most of the samples were drawn from the community, despite the fact that there is an urgent need for studies focusing on the clinical population and those who have reported/been accused of CPV within the judicial system (Moulds et al., 2018; Moulds, Day, Mildred, Miller, & Casey, 2016), particularly since a higher rate of physical CPV has been found among these populations (Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2010; Kennedy et al., 2010; Kuay et al., 2016; Simmons et al., 2018). The lack of studies carried out with specific samples of non-conventional families, such as adoptive families (Selwyn & Meakings, 2016), is also striking.

In relation to sample characteristics, very few studies used both adolescents and parents as informants, even though having two sources of information decreases bias in the prevalence data reported (Calvete et al., 2017; Pagani et al., 2009, 2004).

As for types of CPV, more data is required on the prevalence of property damage and economic abuse (Murphy-Edwards & van Heugten, 2018), and violence towards siblings (Kuay et al., 2016).

The most commonly considered theories were cognitive-behavioral, psychodynamic and psychosocial ones, as well as specific explanatory constructs. The advantage offered by the ecological model for analyzing variables with multiple influence levels (Hong et al., 2012; Simmons et al., 2018) was clear, as was the usefulness of the systemic model and constructivist theory for studying the dynamics that may contribute to the emergence or maintenance of this problem (Coogan, 2014; Pereira & Bertino, 2009). In many cases, the construction of the meaning of the violent act influenced parents' decision regarding whether to seek help, the impact it had on them and their recovery (Murphy-Edwards & van Heugten, 2018).

Of the various different factors linked to CPV, family dynamics and individual factors seem to have a particularly strong influence and should be taken into account during prevention efforts (González-Álvarez, Morán Rodríguez, & García-Vera, 2011; Pérez & Pereira, 2006). During therapeutic work, special emphasis should be placed on exploring adverse events (Nowakowski-Sims & Rowe, 2017), direct and indirect violence (Calvete, Gámez-Guadix, et al., 2014) and mental health problems among both adolescents and parents (Cottrell & Monk, 2004; Laurent & Derry, 1999), since these have been identified as high risk factors.

CPV often occurs simultaneously with teacher abuse (Ibabe, Jaureguizar, & Bentler, 2013a; Jaureguizar & Ibabe, 2012), dating violence (Izaguirre & Calvete, 2017), school bullying (Calvete, Orue, Gámez-Guadix, et al., 2015) or sibling abuse (Castañeda et al., 2012; Holt, 2011; Kuay et al., 2016; Laurent & Derry, 1999; Routt & Anderson, 2011; Selwyn & Meakings, 2016); which demonstrates the need to implement prevention strategies in different fields, particularly in light of the fact that positive relationships at school (Ibabe et al., 2013a) and adherence to prosocial behaviors (Ibabe & Bentler, 2016; Jaureguizar & Ibabe, 2012; Jaureguizar, Ibabe, & Straus, 2013) have been found to be protective factors.

In sum, the review carried out enabled an exhaustive identification of existing studies, providing a useful summary which nevertheless has some limitations. The first of these is that, by selecting empirical evidence published only in English or Spanish, information contained in studies written in other languages was overlooked. Another limitation is that, due to the heterogeneity of the eligible studies, it was necessary to identify different sources of variability and divide them into subgroups for analysis.

Conclusions

The convergence of risk factors at the macrosystem, exosystem, microsystem and ontogenetic levels contributes to the development of CPV. Future research may wish to explore the narrative construction of CPV by the media and professionals in more depth, and to identify how this process influences families. Furthermore, no cross-cultural analysis has yet been carried out of this phenomenon.

It is important to explore whether parents who are victims of CPV have a history of violence themselves, and other potential areas of interest include the functioning of the family system and coping strategies for aggression.

texto en

texto en