Introduction

Gender violence is defined as any act of violence against women that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion, or arbitrary deprivation of freedom occurring in both public and private life (United Nations, 1993). Likewise, gender violence poses a major global public health problem that can affect any woman. The number of victims of gender violence is alarming: around 38% of female homicides are due to spousal violence, and 35% of women have suffered physical or sexual violence by their partner or other men throughout their life (World Health Organization, 2016). Because of their exposure to abuse, female victims of gender violence show higher scores on psychopathological variables associated with emotional distress such as anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and maladjustment, as compared to nonvictimized women (Sarasua et al., 2007). In this regard, health professionals play an essential role in identifying and helping women victims of gender violence. Adequate awareness and training on the subject are essential for recognizing the possible indicators of gender violence (Shearer et al., 2006).

Gender violence can be identified with greater or lesser difficulty depending on how it manifests. People recognize violent behaviours more easily when related to manifest violence like physical or sexual violence than when it is a subtle violence like psychological violence (Novo et al., 2016). In the same way, some variables such as sexist beliefs (Herrera et al., 2014; Yamawaki et al., 2009), culture (Shiu-Thornton et al., 2005), tolerant attitudes towards the control and devaluation of women (Government Delegation for Gender Violence, 2014), or interpretation of a violent situation (Herrera & Expósito, 2009), can influence the identification and perception of violence by minimizing its severity.

Sometimes, despite having objective indicators of abuse and acknowledging having suffered violent behaviour, some women are unable to perceive it or identify themselves as victims of gender violence (Hamby & Gray-Little, 2000; Instituto de la Mujer, 2006). In this regard, Campbell et al. (2003) found that half of the victims killed by gender violence did not consider themselves to be at risk of death. This presents a problem because the victim's perception of the violent situation is a fundamental axis for predicting the recidivism risk of gender violence (Cattaneo et al., 2007; Heckert & Gondolf, 2004a) and for their protection. In contrast, women who have not been victims of gender violence might distance themselves and blame battered women for the violent situation in which they are in, due to the fear that the same situation will happen to them at some point in their own lives (Yamawaki et al., 2009).

Hence, to adequately address violence against women due to gender inequalities, it is necessary to become aware of gender violence as a social problem that should not be underestimated. In this line, exploring and analysing the available findings on how gender violence is perceived and identified will be relevant for scientific advancement.

For this, bibliometric studies are useful because they allow relevant information on a topic of interest to be obtained, structured, and quantified by highlighting keywords, the most relevant authors, the main sources of publication, collaborations between countries, and other types of data (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017; Holden et al., 2005). Publications are analysed through bibliometric indicators, taking into account the number of articles and the number of citations they receive (Dorta-González & Dorta-González, 2010), which facilitates the selection of impactful journals in which to publish. For researchers, knowing the means through which to disseminate their scientific works is a priority because the journals in which they publish can guarantee their work's impact and visibility (González-Sala et al., 2017). In the same way, the bibliometric methodology is fundamental for evaluating scientific production and determining the progress of research in scientific fields such as psychology (López & Osca-Lluch, 2009).

At present, although some bibliometric works on gender exist (Arias et al., 2016; Morais et al., 2016; Söderlund & Madison, 2015), no studies have analysed the scientific production available on the perception and detection of gender violence or on identifying abused women. Therefore, the objective of this study was to quantify and analyse the available scientific activity regarding the perception and detection of gender violence by the general population, battered women, and the professionals who care for them as well as regarding identification as victims of gender violence. The secondary objectives were to (a) analyse the evolution of scientific production on the topics; (b) determine the keywords most frequently used by the authors; (c) determine the scientific activity and impact of the main journals and institutions; (d) study the most productive authors on the search topic as well as the research collaboration network among countries; and (e) identify the most cited works on the topic of interest.

Method

Materials and Units of Analysis

A bibliographic search was carried out in the international and multidisciplinary database Scopus (Elsevier) because it includes many indexed journals and is one of the most commonly used databases for conducting bibliometric studies (Osca-Lluch et al., 2013). Scopus provides the Scimago Journal & Country Rank (SJR), a bibliometric indicator that measures a scientific journal's impact or prestige. This indicator is calculated using the citations received by the journals in a 3-year period (González-Pereira et al., 2010).

The Web of Science (WoS) database owned by Clarivate Analytics is adequate for this type of study. However, Scopus was considered more appropriate for several reasons. Firstly, Scopus allows for more exhaustive analysis of international scientific activity and collects journals from more countries. It also includes a larger number of scientific sources (more than 15,000 journals, compared to the 9,000 that WoS offers) and citable documents. Finally, Scopus has greater thematic coverage in the areas of science, technology, and medicine, as well as in the social sciences, with which we are concerned in this study (Bosman et al., 2006).

Design and Procedure

This research was a quantitative study with an ex post facto bibliometric historiography design (Montero & León, 2007). In February 2020, a search was carried out on the Scopus database introducing the following formula: (“self-perception” OR perception OR recognition OR identification OR detect) AND (“gender violence” OR “gender-based violence” OR “dating violence” OR “partner violence” OR “victims of gender violence” OR “violence against women”) AND (women OR men OR student OR police OR "health professional”). The search was filtered by title, abstract, and keywords. All of the documents available from Scopus were included without being limited by subject area or temporality, obtaining 2,152 results. Subsequently, these documents were manually reviewed by title and summary to reduce the document noise, and 974 final documents were exported in BibTeX format for subsequent statistical management.

Data Analysis

The data were analysed with the statistical analysis program R (R Core Team, 2018). Specifically, the Bibliometrix package was used (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017). The results were analysed quantitatively, taking into account the development in the field; the contributions by year and journal; the most prolific authors, institutions, and coauthors; the most frequent keywords; and interactions by country.

Results

The 974 final analysed documents were published between 1984 and 2020, of which 162 had single authorship, 853 were original articles, 58 were review articles, 33 were press articles, 13 were book chapters, seven were conference documents, six were notes, three were books, and one was an editorial. Most of the documents were published in English (n = 904), and the rest were in Spanish (n = 46), Portuguese (n = 31), French (n = 10), German (n = 2), Italian (n = 1), Croatian (n = 1), Hebrew (n = 1), Japanese (n = 1), Russian (n = 1), and Turkish (n = 1). Likewise, 465 documentary sources were identified, as were 2,758 authors (150 single authors), 1,598 keywords per author, 160 journals, 159 institutions, and 79 countries. The average number of citations per document was 15.19, the average number of authors per document was 2.83, the average number of co-authors per document was 3.37, the average number of documents per author was 0.35, and the collaboration index among authors was 3.21.

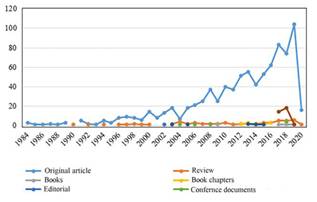

Annual scientific production on the topic increased gradually ever since the publication of the first studies in 1984, with an annual growth rate of 4.76%. Since 2004, the publication of scientific documentation on the perception and detection of gender violence has increased significantly, reaching a peak in 2019 with the publication of 114 articles (Figure 1). Among the annual evolution of the types of documentation produced, the publication of original articles stood out (87.58%) every year (Figure 2).

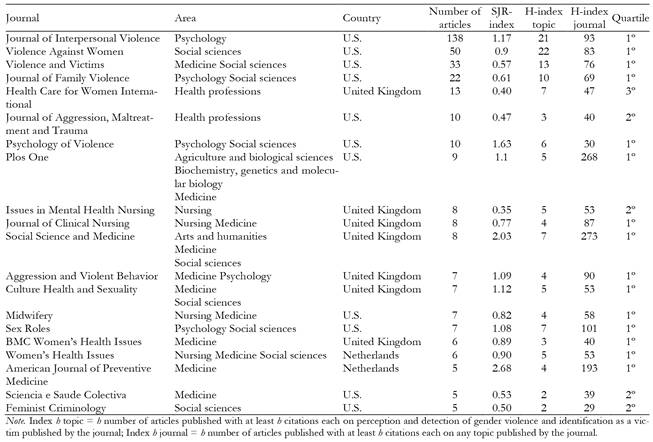

The documents were distributed mainly in the thematic areas of social sciences (n = 395), medicine (n = 393), and psychology (n = 324). The Journal of Interpersonal Violence stood out with the publication of 138 articles, followed to a lesser extent by Violence Against Women (n = 50), Violence and Victims (n = 33), and the Journal of Family Violence (n = 22). Table 1 shows the 20 most productive journals on this topic, half of them being published in the United States (U.S.) and the rest in the United Kingdom (n = 7), the Netherlands (n = 2), and Brazil (n = 1). All are between the first and third quartiles.

Figure 3 shows the 20 main authors of scientific productions on the search topic, as well as the evolution of their research activity over the years on the perception and detection of gender violence and on identification as a victim. Among the main keywords used by all of the documents' authors, the use of the terms “intimate partner violence”, “domestic violence”, “violence against women”, and “dating violence” stood out, occurring 260, 202, 76, and 58 times, respectively. Less frequently used were the terms “perceptions” (n = 11), “gender roles” (n = 10), “social norms” (n = 9), “victims” (n = 8), and “assessment” (n = 7), among others (Figure 4).

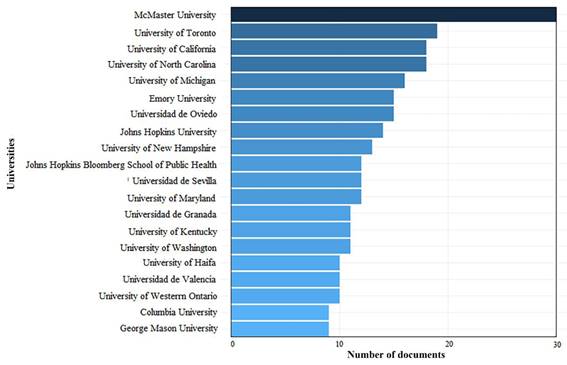

On the other hand, all 20 institutions with the most published works were universities. In first place was McMaster University, with 30 articles and located in Canada, followed by the University of Toronto (n = 19), the University of California (n = 18), the University of North Carolina (n = 18), and the University of Michigan (n=16) located in the United States. The rest of institutions are located in the United States, Spain, Canada, and Israel.

Likewise, of the 79 countries producing works on the topic, 10 countries reported more than 10 documents, and the United States stood out notably with 305 documents and 6,717 citations. A majority of papers were published by a single country (87.28%), compared to a minority of papers published in collaboration with other countries (12.72%; Table 2). The collaboration network among countries can be seen in Figure 6.

Finally, among the documents analysed, the 25 articles with more than 100 citations were considered (Table 3). Among the three most cited articles, the article “Accuracy of 3 Brief Screening Questions for Detecting Partner Violence in the Emergency Department” (Feldhaus et al., 1997), published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, stood out for being the most cited, with 393 citations. In second place, with 316 citations, was a meta-analysis study entitled “Women Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: Expectations and Experiences When They Encounter Health Care Professionals: A Meta-Analysis of Qualitative Studies” (Feder et al., 2006), which was published in the journal Archives of Internal Medicine. In third place was the article “Stop Blaming the Victim: A Meta-analysis on Rape Myths” was published in 2010 in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence and had more than 290 citations.

Of the documents, 72% were empirical studies. Some of them focused on detecting and responding to gender violence (Feldhaus et al., 1997; Gutmanis et al., 2007; Waalen et al., 2000), as well as on perceptions and attitudes towards gender violence (Kim & Motsei, 2002) among health professionals. Among them, the most cited article was “Accuracy of 3 Brief Screening Questions for Detecting Partner Violence in the Emergency Department” (Feldhaus et al., 1997), whose main objective was to validate a brief three-question instrument for detecting physical violence and women's perception of their safety.

Other empirical studies focused on exploring the perceptions and attitudes towards gender violence by female victims, perpetrators and/or students (Arias & Pape, 1999; Avery-Leaf et al.,1997; Banyard & Moynihan, 2011; Dobash at al.,1998; Fabiano et al., 2003; Fanslow & Robinson, 2010; Glass at al., 2001; Heckert & Gondolf, 2004b; Hegarty et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 1995; Torres, 1991; Rose at al., 2000; Wolf at al., 2003). Among the studies focusing on victims' perceptions of gender violence, the article “Battered Women's Perceptions of Risk Versus Risk Factors and Instruments in Predicting Repeat Reassault” (Heckert & Gondolf, 2004b) explored the prediction of gender violence recidivism using the victim's perceived risk as compared to the use of risk-assessment instruments. The results showed better prediction by the victim in a sample of 499 women.

Half of the empirical studies analysed were conducted with women victims of gender violence (Arias & Pape, 1999; Dobash et al., 1998; Fanslow & Robinson, 2010; Felhaus et al., 1997; Glass et al., 2001; Heckert & Gondolf, 2004b; Hegarty et al., 2013; Rose et al., 2000; Torres, 1991; Wolf et al., 2003). The rest of them were carried out with aggressors (Dobash et al., 1998), health professionals (Gutmanis et al., 2007; Hegarty et al., 2013; Kim & Motsei, 2002; MacMillan et al., 2009), the general population (Glass et al., 2001), and students (Avery-Leaf et al., 1997; Banyard & Moynihan, 2011; Fabiano el al., 2003; Johnson et al., 1995).

On the other hand, 28% of the documents were theoretical studies aimed at synthesizing and analysing the available information about (a) the perceptions among victims of gender violence on the healthcare they received (Feder, Hutson, Ramsay, & Taket, 2006); (b) the social perception and acceptance of myths about sexual aggression against women (Suarez & Gadalla, 2010); (c) the relationship between risk perception and sexual victimization among women (Gidycz at al., 2006); (d) the perceptions of gender violence, taking into account cultural norms and individual characteristics (Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2010); (e) the diagnosis, process, and identification of gender violence (Walker, 1989); (f) health professionals' perceptions regarding the perceived barriers to detecting and acting on gender violence as well as the effects of interventions to increase these professionals' perceptions of and capacity to detect cases of gender violence (Waalen et al., 2000); (g) the relationship between perceptions and attitudes towards gender violence and its influence on individual and societal responses (Flood & Pease, 2009); and (h) the fulfilment of criteria for detecting gender violence in healthcare (Feder et al., 2009).

The results show a wide temporal range in the study of the topic (1989-2013), as well as a notable interest in the scientific production of studies on how different actors (victims, aggressors, health professionals, and/or students) perceive gender violence. However, among the main articles, there were no specific studies on women's identification as victims of gender violence.

Discussion

The present study was aimed at covering the lack of bibliometric studies that involved collecting and analysing the available scientific works on the perception and detection of gender violence as well as on identification as victims. The data obtained allow easy access to this information and clarifies it, favouring the approach used.

The increase in scientific production over time denotes a social change in interest and understanding of the problem. The most cited works focus on the perceptions and attitudes towards gender violence by victims, aggressors, health personnel, and students as well as on the detection of gender violence in health care.

Regarding studies focusing on victims of gender violence, Heckert and Gondolf (2004b) highlighted the importance of women's perceptions of recidivism of gender violence. They pointed out that this perception is a significant predictor of future victimization, even during the 15 months following the assessment. Likewise, Cattaneo et al. (2007) agreed on the importance of assessing the victim's perception of the violent situation, as a key aspect in predicting recidivism and preserving their safety. In this respect, Fanslow and Robinson (2010) indicated that one of the main reasons why victims of gender violence do not seek help is because they normalize the situation or do not perceive it as serious. Doing so could be dangerous because if the woman is incapable of perceiving violence in her relationship with her partner and making an interpretation adjusted to reality, then it will be difficult for her to assess the risk to her personal integrity and to make self-protection decisions. Therefore, as Andrés-Pueyo and Echeburúa (2010) pointed out, predicting the appearance of future violent behaviour allows one to assess risk and make graduated and re-evaluated decisions with respect to the prognosis. Continuing research along these lines is fundamental because it is necessary to become aware of a problem's existence, magnitude, and severity in order to confront it.

On the other hand, as some of the main studies showed, health professionals are essential in detecting gender violence. According to Taft et al. (2013), battered women tend to have worse general health, problems in pregnancy, and more premature deaths than women who do not suffer gender violence do. Similarly, battered women visit the doctor up to three times more often than other women do; thus, health centres should be encouraged to evaluate warning signs of gender violence among their patients (Campbell, 2002). To this end, according to previous studies (Shearer et al., 2006), health professionals' training and ability to perceive signs of gender violence will be essential to take action against this problem.

Regarding the main authors, Jacqueline Campbell stood out for her continuity and persistence in studying the topic over time, starting with her first publications in 1994 and maintaining her scientific production to the present day. Likewise, the rest of the authors contributed significantly to the advancement of knowledge on perceiving and detecting gender violence as well as identification as victims. In this line, we should note the importance of collaboration among authors, as well as among institutions, because a higher rate of international collaboration could be related to scientific publications having greater impact and visibility (Alonso-Arroyo et al., 2005). The results show a low level of international cooperation, with the majority of countries presenting single authorship. However, the high numbers of countries (n = 79), institutions (n = 159), and professionals (n = 2,758) involved in scientific production on the topic denote an interest amongst researchers worldwide and favours progress in the field of gender violence.

Finally, to identify the studies of interest, the authors mainly used terms related to gender violence, violence towards partners, and domestic violence (“intimate partner violence”, “violence against women”, “dating violence”, or “domestic violence”). Although gender violence is recognised worldwide, not all countries have the same legislation or use the same nomenclature to refer to violence against women. In order to obtain results with more precision, the search formula did not include the term “domestic violence”.

Regarding the limitations of the study, the results obtained should be interpreted with caution because the chosen methodology did not take into account the grey literature and could have excluded certain works related to the topic that may provide information of interest. However, this limitation was minimized by the wide coverage of journals and the number of documents available on Scopus. Likewise, Valderrama-Zurián, Aguilar-Moya, Melero-Fuentes, and Aleixandre-Benavent (2015) pointed out the need for greater rigour in the registration of accessible documents in Scopus because duplicate documents sometimes appear. This could affect the interpretation of the results obtained in bibliometric studies. Taking into account this limitation, articles resulting from the search were manually screened to ensure the lack of duplicates.

Conclusion

The findings allow one to see the current state of the topic of study with respect to scientific production, as well as its dispersion over time. The structuring and analysis of the results provide a starting point for future research and contribute to advancing the scientific knowledge on gender violence. In this line, it will be convenient to explore the governmental commitments adopted by each country at the national and international levels for preventing and approaching gender violence, as well as other related variables that allow one to understand the differences regarding the interest in studying this topic within each country. In the same way, theoretical studies that review and synthesize the available literature in this regard will be essential to determine what elements are influencing the identification of gender violence.

Hence, future research should continue to explore how different actors perceive gender violence because this constitutes the first step for effectively addressing the problem. The ability to identify even the most subtle signs of violence will be essential to prevent fatal consequences and adopt appropriate safety behaviors for the victim.

texto en

texto en