Introduction

There is still a clear gender gap in leadership positions maintained on our days (Bear et al., 2017; Hoyt, 2010; Qian, & Yavorsky, 2021). This gap is higher in leadership positions with a higher number of women in basic positions and higher number of men than women in upper positions, denominated “scissors-effect” (Glass & Cook, 2016). Studies analyzing this gender gap (see Hernandez et al., 2014 for a systematic review) discuss mainly stereotypes and the prejudice against women leaders (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Garcia-Retamero & Lopez-Zafra, 2006; Koenig et al., 2011), about the difficulties they may face in attaining leadership roles (Killeen et al., , or about individual variables that may influence their aspirations (e.g., motivation, Elprana et al., 2015 or power motivation, in Germany, Schuh et al., 2014 or in Spain, Hernandez et al., 2016).

Despite there is a significant pressure to increase gender diversity at leadership levels (Walsh et al., 2016), the progress has been slow (Sealy et al., 2016). The research seeks to identify the reasons for the underrepresentation of women in leadership positions (Eagly & Carli 2007; Hoyt, 2010). Many factors contribute to this gender gap in leadership, such as perceptions of role incongruity between leadership and traditional gender roles (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Heilman, 2012), stereotyping processes (Heilman, 2012; Rudman, 1998), or organizational barriers for women (Longman et al., 2018; Milkman at al., 2015). Eagly and Karau (2002) proposed the role congruity theory, suggesting societal gender roles dictate that men should demonstrate agentic attributes, such as assertiveness and dominance, and women more communal attributes, such as compassion and collaboration. This gender role distribution represents a contradiction between their gender role and a leadership role.

Referring to stereotypes, we could discuss the differing level of ambition to leadership positions women and men may have. In fact, studies with young boys and girls (Blackhurst & Richard, 2018), or with university students (King, 2008), show that they have similar levels of ambition or even that female students express higher career aspirations than male counterparts (Watts et al., 2015). Furthermore, results show that university graduates in general expect to attain future upward social mobility (Shane & Heckhausen, 2017). However, some studies suggest that women in the workplace do not have the same levels of ambition as men do (Litzky & Greenhaus, 2007; Powell & Butterfield, 2003), leaving to pursue roles with better work-life balance or flexibility (Lewis et al., 2015). The well-documented obstacles along women career for becoming a leader have been demonstrated mainly on employees or students separately, or women exclusively. However, little is known about students´ vs employees´ antecedents of ambition about leadership from a gender perspective. Thus, we could hypothesize that changes occur in women´s ambitions through time and, therefore, regardless of the participant´s gender, students would show higher ambition than employees (H1a), but women employees would be less ambitious than men employees (H1b).

If so, which are the aspects that make women change their ambition level when they are employees? Young student women may think that society is gender-fair, whereas older, employed women may be more aware of the constraints and biases that women face in the workplace, producing a labyrinth of challenges (Eagly & Carli, 2007; Streets & Major, 2014). Moreover, this may make employee women decrease in their ambitions interest more than men do. However, other situational aspects of their family situation or the help women and men may have in their daily lives could hinder or promote their ambitions (Harman & Sealy, 2017). In fact, women in the EU have worse conditions than men. For example, women earn 16% less than men and there are a third of women among managers (Eurostats, 2018). This could be especially the case in Mediterranean countries (e.g., Spain) as sociologists assert that, in these countries, the gender inequality is clear and women total work (for pay and at home) exceed 1.5 hour that of men compared with north Europe and USA, being the worst for working women (Burda et al., 2013). In Spain, women dedicate 26.5 hours a week to non-remunerated tasks (i.e. caring for others, household chores), compared to just 14 hours for men. Furthermore, women on average earn 23% less than men (Eurostats, 2018).

Ambition can be necessary in order to achieve leadership positions in the workplace (Hogan & Kaiser, 2005). However, it has received scarce attention in social psychological literature (Hall, 2017). In general, results show that although women often self-report similar ambition levels as men, they are perceived by others to be less ambitious than men (Ellemers et al., 2004). This could have an impact on the positive or negative affect that a possible promotion may instil. Moreover, the perceived consequences of a promotion would impact the final decision about promoting. In fact, a promotion may have consequences affecting both in the relational and instrumental areas and thus, influence men and women in their decision. However, this could be moderated by individuals' core self-evaluation. Core self-evaluation (CSE) represents the fundamental appraisals individuals make about their self-worth and capabilities (Judge et al., 2003). CSE is conceptualized as a higher order construct composed of broad and evaluative traits (e.g., self-esteem and generalized self-efficacy). The meta-analysis by Chan, et al. (2012) supports the relation between CSE and various outcomes, inclu-ding job and life satisfaction, in-role and extra-role job performance, and perceptions of the work environment (e.g., job characteristics and fairness). It has also been suggested that CSE as a motivational trait is useful for prediction of various goal-setting activities and coping strategies (Haynie et al., 2016; Kammeyer-Mueller et al., 2014) along with predictions of key career-related outcomes (Gurbuz et al., 2021).

Finally, affect likely plays a fundamental role in the decision to promote. The term affect describes any feelings, emotions, or moods that a person experiences, and could be divided into positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) (Watson et al. 1988). Results show that affect dimensions relate to a range of psychosocial experiences at work (Kaplan, et al., 2009), thereby influencing the moods and emotions individuals experience. Thus, it is likely that affect plays a fundamental role in the decision to promote, but no previous study has analyzed this.

Bearing all these aspects in mind, we propose that a decision to promote is influenced not only by ambition, but also by other psychosocial variables; such as consequences for their lives or how tasks and parenting are distributed among the couple, along with the positive or negative effect that may be provoked. In this study, we tested a conceptual model (Figure 1) about the relationships between ambition about a leadership position, and positive and negative affect, instrumental and relational consequences and the final decision of accepting the promotion.

Method

Participants

The initial sample was 739, but seventy-seven questionnaires were discarded because participants´ age was out of normal range (students older than 26 years or employees younger than 25) maybe indicating that they were part of both statuses, and 37 were eliminated for incomplete or extreme responding. Finally, the participants were 625 (286 men and 339 women) from two different statuses (379 students and 246 employees). Mean age for the students was 19.14 (SD = 1.86, range 17-25) and for the employees was 40.13 (SD = 9.10; range 25-61).

Procedure and Design

The eight female and eight male surveyors asked students and employees located in different settings (campus, classes, firms, and homes) to participate in this study voluntarily. Before distributing the questionnaire to those who consented (85%), the surveyor asked participants about their current studies or employment and received a questionnaire that presented a promotion situation (see a situation of promotion below). Then they completed several scales about their beliefs about the consequences of the promotion, their core self-evaluations that would result from the promotion, their level of ambition, positive and negative emotions the promotion would cause, and their gender role ideology. The resulting between-subjects factorial design was 2 (Participant´s gender: male vs female) × 2 (Status: student vs employee).

Situation of a future promotion.

Participants were asked to imagine how they would react to a promotion to a leadership position in their future organization within their field of study (for students) or their present organization (for the employees). Consistent with similar studies (e.g., Chui & Dietz, 2014; Hershcovis & Reich, 2017; Lopez-Zafra & Garcia-Retamero, 2012), each questionnaire included the following written scenario describing a situation of a future promotion: a person who works in an organization has the opportunity to promote for a leadership position occupying the manager position because she/he has the accurate qualification. The promotion implies to manage a group of fifty subordinates at least, and an increase of the hours dedicated to work. Furthermore, the person who promotes would earn a higher salary. Participants were asked to imagine they are this person who has the possibility to promote, and then they had to answer questions about the situation.

Instruments

Instrumental and relational consequences of the promotion. Reasons were selected from a previous study (Study 1) that had two phases. In the first phase, a group discussed about the consequences of a promotion for men and women (n = 20; 7 men and 13 women). From their pool of reasons given, twelve possible reasons for accepting or not a promotion were extracted and included in a pilot study, a second phase, (n = 105; 55 women and 50 men; age range = 22-60; Mean age = 38.8; SD = 7.48). Participants had to rate from lowest influence (1) to the highest influence (5) in their decision. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index for sampling adequacy was 0.71, and Bartlett test was significant (χ 2 = 752.27; p < .001) indicating that performing factorial analysis was pertinent. Principal component with Varimax rotation was performed. From all the analyses, we took eight out of twelve reasons derived from factor analyses. These reasons comprised two factors: five items related to positive consequences for instrumental or individual motivation (e.g., I would have greater power) and three items related to near relations (e.g., I would have pro-blems with my mate). Negative items were reversed. The higher the score, the higher the positive consequences for ins-trumental or near relations. The omega reliability was 0.78.

Core self-evaluations scale (CSES;Judge et al., 2003; Spanish version by Judge, Van Vianen, & De Pater, 2004). On 5-points Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly), individuals score 12 items that load on a single unitary factor measuring the fundamental evaluations that people make about themselves and their functioning in their environment (e.g., “I determine what will happen in my life”, Judge, 2009). Previous empirical findings support the one-factor solution demonstrating strong internal consistency (i.e. Stumpp, Muck, Judge, & Maier, 2010 reported an alpha = .86 with German workers or the .71 found in Iranian samples by Sheykhshabani, 2011). In our study, the omega reliability was 0.70.

Ambition Scale. On 5-points scale, participants answered 7 items. Five of the items were derived from Van Vianen´s (1999) ambition for a managerial position scale (i.e. If a ma-nagement position will be offered to me in the near future, I will accept) and two new items were included to test the ambition for general promotion (i.e. “I do not give up if I do not get a promotion in my job”, “I wait for an opportunity and I keep preparing myself”). These two new items were obtained through a group discussion about ambition and the need to having success and promotion (Study 1). For this study the omega reliability was 0.54.

Positive and Negative Affect. (PANAS, Watson et al., 1988; Spanish version by Sandín et al., 1999). This instrument is comprised of 20 items on a rating scale of 5 Likert points (Estevez-López et al., 2016). In this study, we asked participants to think about deciding to promote and response to the emotions that provoke this decision to them. Affect is mea-sured in two dimensions; positive affect (PA) reflects the extent to which a person feels enthusiastic, active, alert, energetic and rewarding participation. Negative affect (NA) is a general dimension of subjective distress and unpleasant involvement including a variety of aversive emotional states, such as disgust, anger, guilt, fear and nervousness. The omega reliability was 0.84.

Gender Role Beliefs Scale (GRBS;Kerr & Holden, 1996). On 7-points Likert scale women answered to 20 items that assess the gender role ideology, that is, the prescriptive beliefs about gender roles1. The higher the score, the more feminist ideology. These items were constructed from a combination of earlier scales measuring gender role ideology. This scale was not available in Spanish. Thus, we made the translation and adaptation of the scale following the recommendations of the International Test Commission guidelines (2000). The scale was translated into Spanish by one researcher. After that, a native English speaker, who did not know the original version, made the back-translation. The two researches then compared the two versions and the English speaker researcher pointed out the similarities and differences. The Spanish speaking researcher and the native English speaker commented the di-fferences. The final translation was confirmed by consensus. It constitutes only one factor and in our study, omega reliabi-lity is 0.86.

Decision of a promotion. A set of three questions rated of seven Likert points were included to evaluate the extent the intention the person had to accept the position (accept), how she/he evaluated their decision in case of accepting (value), and how they thought important people for them would react supporting or not their decision (support). In view of the affinity between the questions, the main component analyses showed sufficient evidence that there exists at least one common factor underlying the observed variables. Results showed a KMO value greater than .60 indicative of factorability (Mulaik, 2010).

Equality. Participants were asked to rate the percentage of time they (or their parents) devoted to the childbearing. An index was extracted from the different patterns indicating that they had an equal dedication to the children (1) or unequal (2). Equality was considered on the basis of the Spanish Organic Law 3/2007 for the effective equality between women and men that proposes a range of 40-60% rate to be equal.

Sociodemographic variables. Participants were asked about their age, gender, marital status, the number of children they had.

Results

Factorial validity and reliability of the measures

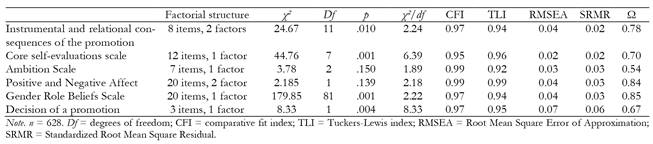

First, confirmatory factor analyses of the instruments used in this study were carried out. The results showed a factorial structure according to the original instruments, as well as an appropriate adjustment (see table 1). The factorial loads of each instrument were more significant than .50, which indicates a proper contribution of each of the items to their corresponding factors (Brown, 2014). On the other hand, the scales' omega reliability results show appropriate indexes from .54 to .85 (McDonald, 1999).

Comparative analyses

Second, we explored the effect of status on ambition by conducting an analysis of variance (ANOVAs) to test whether students would show higher ambition than employees (H1a), and to compare women and men ambition in employees (H1b). As we expected in H1a, regardless of the participant´s gender, students showed higher ambition than employees (M = 3.84, SD = .53 vs. M = 3.58, SD = .79, respectively; F(1, 616) = 24.17, p < .001, η p 2 = .038). However, regarding H1b, unexpectedly no gender differences emerged in the general level of ambition between employees men and women (M = 3.63, SD = .71 vs. M = 3.53, SD = .86, respectively; F(1, 616) = .943, p = .332, η p 2 = .004). Thus, the complexity of influences on the ambition level was tested by path analyses.

Path analyses

To examine the impact that the ambition about a leadership position and positive and negative affect, instrumental and relational consequences and equality in the relations on decision of accepting the promotion (H2), we used a path analyses approach using AMOS 20 software. To evaluate the goodness of fit of the model were used Chi-square (X 2 /df), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) (Reise, Scheines, Widaman, & Haviland, 2013). As shown in Figure 2, the model included as mediational the Positive and Negative affect, Instrumental and relational consequences, and showed a satisfied fitness to the data: X 2 /df (31, N = 625) = 2153, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.04; SRMR = 0.03; CFI = 0.97. The final model has a sum of direct and indirect effects that explains a 51% of the decision variance.

The test results' invariance (Byrne et al., 1989) showed that differences between males-females and students-employees in the model were significant; X 2 (6, n = 625) = 16.507, p = .01. Therefore, Table 2 presents the results of the standardized regression weights for each group by gender and status.

Discussion

The present research contributes to the literature by comparing students' vs employees´ ambition along with personal background (e.g., gender role beliefs, equal distribution of pa-renting or the importance given to consequences of promotion) to propose a more comprehensive model of elements affecting the decision of promoting. In this study, we propose a path model of relations by comparing the antecedents of ambition between students vs employees. Our model brings the relevant role of psychosocial variables such as consequences of the promotion, parenting distribution among the couple, along with the positive or negative effect that may provoke barriers in women career.

In general, our results show that students are more ambitious than employees. However, when analyzing the impact of ambition on the decision of accepting a leadership position we observe that positive affect generated by imagining a promotion is the key aspect to finally decide to accept the promotion in all participants whereas negative affect negatively predicts the final decision only in students, regardless of gender, and this is predicted by CSE but not by levels of ambition. Thus, when deciding about a promotion, students with a lower CSE would think negatively about it, and their perception about negative consequences for their relations would indirectly influence them in their decision. On the contrary, participants who feel positively about the promotion would accept the promotion more probably, regardless the status and gender. Moreover, positive affect mediates the relation bet-ween ambition and decision of a promotion by also perceiving positive instrumental consequences of the promotion (e.g., power, status, etc.) mainly in students.

Regardless of their gender, students were more ambitious than employees. These results are in agreement with studies in which boys' and girls' university students show similar le-vels of ambitions (King, 2008). An explanation could relate to the malleability of gender stereotypes (Diekman & Eagly, 2000). In particular, we think that a double paradox is present in Spain. The rapid change toward greater equality (Gartzia & Lopez-Zafra, 2014, 2016) could affect students' perceptions about their future possibilities, but at the same time, gender roles are still present making back and forth steps (Bustelo, 2016; Sáinz, et al., 2018). However, when considering status, our study shows that employees have lower levels of ambition than students, but no gender differences were found. This contradicts other studies that suggest that women workplace do not have the same levels of ambition as men (Litzky & Greenhaus, 2007; Powell, & Butterfield, 2003). Thus, we could conclude that ambition decreases once a person is working and faces the reality. However, this relation is more complex and depends on how individual and situational varia-bles instill a positive or negative affect. In this sense, Diener and Diener (1996) considered that even more important in explaining well-being is the differential impact of other explanatory variables within specific groups (i.e. gender, marriage).

Our results show that equality in parenting impacts the willingness to promote by the mediation of positive affect, but not of negative affect. Thus, the decision of promoting is positively determined by the positive affect that this situation generates on employees. At the same time, positive and negative affect are determined by CSE in all participants (students and employees) and predicts the promoting decision by the mediating role of ambition. Besides, gender role beliefs predict instrumental and relational consequences, the more feminist, the more positive the instrumental consequences are perceived, whereas a less feminist ideology implies to perceive more negative relational consequences. Furthermore, the more feminist the more equality in parenting. However, parenting equality negatively predicts positive affect only in female students, maybe because they see negative consequences on the relations, and thus impacts the willingness to promote. No effects emerged for female employees.

Our study contributes to the path to leadership for women careers in several ways. Most studies have focused on students or employees separately, or on women exclusively. In order to overcome this limitation, we compare the antecedents of ambition between students' vs employees, revealing a higher level among students. Considering the many obstacles along the way to a women becoming a leadership position (Eagly & Carli, 2007), we tested a complex model of relationships which revealed a significant contribution related to gender aspirations. Although no gender differences emerged in the general level of ambition between employees' men and women, our model bring the relevant role of psychosocial variables such as consequences of the promotion, or how parenting are distributed among the couple, along with the positive or negative effect that may provoke barriers in women ‘career.

Limitations and future directions

Following similar studies (e.g., Chui & Dietz, 2014; Hershcovis & Reich, 2017; Lopez-Zafra & Garcia-Retamero, 2012), we used a simulated situation of a promotion instead of real facts. In the case of students, this corresponds with the possible selves' simulation, but for employees it would be rather more difficult to know about how their personal situation influences their promotion ambition. For example, we asked about having children but maybe the age of their children impact their decision in present but changes in future. Moreover, our sample included a range of students and employees with different sociodemographic situations in a cross-sectional study. In future studies, researchers could establish more exclusion criteria in order to homogenize the sample. Furthermore, longitudinal studies are necessary to test changes in ambition through the lifecycle.

Practical implications

Women continue to face barriers along with their careers that undermine their ambition of a promotion, and therefore further development of early intervention strategies is needed. Because obstacles of a promotion are well-known at all levels, society should attend to all steps in the career development of women. According to status, students are called to participate in educational programs of gender equality careers. Following recent role-model interventions which evidence positive be-nefits on girls' aspirations in STEM (González-Pérez et al., 2020), educational centers are encouraged to implement strategies to promote ambition on female students in order to reach leadership positions as future workers. Similarly, the family should promote values of gender equality in aspirations of young women because of the opportunity of incorporating skills, traits and experiences into their social roles (Sáinz & Müller, 2018). Regarding employees, becoming a leader involve a new configuration of parenting and so, organizations have the responsibility to introduce facilities in work-family balance, equal distribution of professional criteria for a promotion, and programs to reduce sexism in workplace settings.