Introduction

COVID-19 pandemic has severe impacts on various aspects of individuals' lives. Intertwined with economic and social effects, the psychological outcomes of the pandemic are highly critical (Qiu et al., 2020). The psychological effects of previous epidemics were much more comprehensive than the individuals exposed to the virus, and they continued to negatively affect the lives of individuals for a long time, even after the epidemic. Meta-analyzes addressing the psychological effects of epidemics such as Ebola, MERS, SARS, and COVID-19 pandemic indicate serious psychological problems such as depression, anxiety disorder, low self-esteem, loss of control, post-traumatic stress disorder, and mental disorders, which can endure even three years after the outbreak (Hossain et al., 2020; Brooks et al., 2020). In a study on 669 people who were not diagnosed with COVID 19 in India, a significant portion of the participants stated that they experienced psychological problems such as sleep disorder, paranoia, and anxiety disorder, and 80% needed professional help for their mental health (Roy et al., 2020).

Changes necessitating individuals to stay at home, decreased social interaction, anxiety about the health of self and relatives, economic problems, and uncertainties regarding various variables of life threaten the wellbeing of individuals during the pandemic (Dawson, & Golijani-Moghaddam, 2020; Xiong et al., 2020). Social isolation stands as one of the most frequently applied preventative policies to reduce the spread of the virus. Despite its advantages for protecting individuals' physical health, it necessitates people to isolate themselves, stay at home and lower their physical human interaction, which may bring detrimental consequences for psychological wellbeing (Tull et al., 2020). In this process, the routines and habits of people are threatened, and they try to get used to new rules. As in the popular social campaign “life fits at home”, people try to transfer or rebuild their lives, hobbies, and habits in their homes. With this given pattern of circumstances, most of the possible solutions for the problems brought by social isolation lies in indoor activities that everybody can do at their homes, such as physical exercise, digital socializing, and digital gaming.

While previous studies (e.g., Thompson et al., 2017; Diaz, & Stewart-Ibarra; 2018) on epidemics such as H1N1 Enfluanza (2009), Ebola (2013), and Zika (2016) help us to understand the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is also true that this outbreak includes unique characteristics that require novel studies. Investigating the levels, antecedents, and transformation of the psychological experiences individuals experience is extremely important in terms of the information it will provide for policymakers and practitioners to manage the process effectively. Considering the dynamic nature of the process, the urgency of the studies addressing both between persons and within-person variances comes into prominence. Elements such as the spread of the virus, the total time individuals stay at home, curfews, and travel-related constraints are changing rapidly every day. Besides, the methods developed by individuals and institutions to deal with the process, their level of knowledge about the process, and their levels of getting used to new conditions also change. Each stage of the process has its own characteristics, and it is of great importance to investigate day-level within-person variance.

The main purpose of this study is to analyze the effects of indoor activities on the subjective wellbeing levels of individuals. Using a multilevel approach, the current study aims to determine the levels of happiness and positive and negative affect levels of individuals, their change over time and analyze their relationships with indoor activities (physical exercise, digital socializing, and digital gaming), personality (extraversion) and psychological resilience.

Physical activity and wellbeing

The significance of physical activity for wellbeing is well-established (Kim et al., 2017; Wiese, Kuykendall, & Tay, 2018). Downward and Rasciute (2011) provided evidence for the positive link between sport (67 kinds of it) and the subjective wellbeing of individuals. Physical activity in nature demonstrates stronger connections with emotional wellbeing, where general health is connected with both indoor and outdoor physical activity (Pasanen, Tyrväinen & Korpela, 2014). Regardless of the physical activity environment (indoor, outdoor, or combined), better scores for tension, stress, emotional outlook, and health were observed in psychically active individuals compared to inactive ones (Puett et al., 2014). The link between wellbeing and physical activity is also valid for older adults (Sasidharan et al., 2006), which were required to stay home for a long period (as it was forbidden for people older than 65 to leave home from March 21st to June 1st 2020). Evidence supports the positive effects of physical activity on psychological wellbeing during the pandemic (Maugeri et al., 2020). Studies addressing indoor and outdoor exercise settings consider ‘indoor' as gym centers or facilities that many people come together. Experiments (e.g., Norris, Carroll & Cochrane, 1992) conducted for investigating the link between physical activity and wellbeing recognize the effects of social companionship provided by the exercise activity. Although with this conceptualization, indoor settings are more enabling for social interactions than outdoor settings, the latter has higher restorative quality (Hug et al., 2009). The fitness centers or any kind of public sports facilities (along with many other institutions) were closed due to the pandemic for more than two months, including the duration of the data collection process. Places like the seaside or public parks that are frequently used for jogging or walking were also closed. There were strict lockdowns requiring people to stay at their homes at weekends and holidays (with some workdays in between) during this period. Even when there was no rule-based lockdown, most people preferred to stay home due to the pandemic. All physical exercise people could do was in their houses, which changed the nature of this activity by eliminating the social side of it or reducing the machines or equipment that individuals could use. Although there is supportive evidence for the positive association between indoor exercise and wellbeing, we acknowledge that the circumstances brought by the pandemic and these forms of physical exercise are unique, and the results will be inevitably exploratory in nature.

Hypothesis 1: Daily physical activity at home will be positively related to daily positive affect and happiness and negatively related to daily negative affect.

Online socializing and wellbeing

In their comprehensive meta-analysis, Castellacci & Tveito (2018) list some studies that are pointing the adverse effects of internet usage on wellbeing and communication (e.g., Kraut et al., 1998; Nie, 2001) and some others that are providing positive associations between the variables (e.g., Valkenburg & Peter, 2009; Kraut et al., 2002). They argue that the link between those is complex and personal characteristics and the life domain in which the Internet is used affect the association. If it is used for saving time for enhancing social interactions, it can create a positive impact on wellbeing.

Accordingly, recent studies indicate different natures of associations between variables. Kim (2017) provides evidence for the negative link between online social networking and psychological state. Dhir et al. (2018) showed that compulsive usage of social media induces fatigue, and social media fatigue boosts anxiety and depression.

On the other hand, Coyne et al. (2020), via an eight-years longitudinal study, demonstrated no significant relationship between the time spent using social media and personal changes in depression and anxiety. Law, Shapka, & Collie (2020) showed that online experiences may affect individuals in different ways. Their findings classified respondents into three profiles in accordance with their social acceptance, depression, and anxiety levels. 61% of the participants were in the moderate cluster, and 31% were in the flourishing profile, while only 8% were in the languishing group.

Studies base the adverse effects of using the Internet for social interaction on substituting face-to-face communication and decreasing the physical (actual) human contact, but no studies have ever addressed these associations when using the Internet or digital channels become the only way to interact with others that are not living in the same house.

Coget, Yamauchi & Suman (2002)'s findings revealed that online socializing decreased the levels of loneliness, and this decrease was not statistically different from the impact of face-to-face socializing on loneliness. Kim & Lee (2011) provide evidence for the positive relationship between the number of Facebook friends and subjective wellbeing. Valenzuela, Park & Kee (2009) indicate a positive link between Facebook usage and life satisfaction. Przybylski & Weinstein (2017) indicate a quadratic relationship between digital screen use and mental wellbeing. It is important to note that these findings were mainly developed with adolescent samples and, more importantly, under normal circumstances. Social distancing and lockdowns can change the function, and meaning individuals attribute to digital channels of communication.

Selfhout et al. (2009) indicated that the relationship between depressive symptoms and online socializing is negative for children who have low-quality friendships, as they can have social support from online channels, which they cannot normally have from traditional channels. Although it is not the same situation, there is a resemblance given the circumstances of social distancing and lockdowns, as individuals cannot socialize in the traditional ways, and online channels are providing a solid substitute.

Hypothesis 2: Daily online socializing will be positively related to daily positive affect and happiness and negatively related to daily negative affect.

Online gaming and wellbeing

Findings for the links between gaming and wellbeing in the literature depict a complex picture rather than an agreed-upon nature of the association. The way individuals engage in gaming (obsessive or harmonious) and the time they spent on it (excessive or moderate) is significantly determinative for whether gaming results in positive or negative outcomes (Lafreniere et al., 2009). Also, these associations may be contingent across cultures and countries (Cheng, Cheung, & Wang, 2018).

Some studies suggest a negative link between gaming and wellbeing, especially when it is in an extreme form. Excessive levels of gaming or game addiction are positively related to depression, anxiety, and loneliness (Wang, Sheng, & Wang, 2019). Video game use can have detrimental effects such as suicidal tendencies and interpersonal violence (Ivory, Ivory, & Lanier, 2017).

On the other hand, Halbrook, O'Donnell, & Msetfi (2019) suggested that video games are good for psychological health when used in healthy ways that induce social activity. King et al. (2020) emphasize the role of more balanced styles of gaming for supporting the wellbeing of individuals during the pandemic. Video gaming can reduce stress levels and enhance happiness and mental health through positive emotions, engagement, meaning, and accomplishment (Jones et al., 2014). Even violent games can enhance creativity and emotional wellbeing (Kutner & Olson 2009). Gamers are likely to be generally observed as more antisocial individuals. However, digital gaming can serve as a socializing tool. Online social interaction is an essential moderator in the relationship between video gaming and depressive symptoms (Carras et al., 2017). Individuals with higher online social interaction can relate to a virtual social community, build friendships and show fewer depressive symptoms.

Hypothesis 3: Daily online gaming will be positively related to daily positive affect and happiness and negatively related to daily negative affect.

Extraversion and wellbeing

Extraversion has been generally accepted as a positive predictor for wellbeing as it is assumed that extraverts experience more positive affect and happiness and less negative affect given the same circumstances (McCrae Costa, 1991; Zelenski & Larsen, 1999; Olesen, Thomsen, & O'Toole, 2015: Hervas, & López-Gómez, 2016). “The bulk of the literature on the personality correlates of happiness can be summarized by saying that more extraverted and more adjusted people are happier” (Costa & McCrae, 1980, p.674). Lee, Dean & Jung (2008) report positive relationships between extraversion positive affect and life satisfaction and negative association with negative affect. Harris & Lightsey (2005)'s findings indicate the same relationship pattern and add a positive link between extraversion and happiness. Despite this general view regarding extraversion and wellbeing, we believe the circumstances entailed by the pandemic can reverse this relationship. Compulsory lockdowns, social distancing, and staying at home would be less tolerated by extroverts compared to introverts who are more used to and indifferent to such situations in their normal lives. We propose a negative relationship between extraversion and wellbeing.

Hypothesis 4: Extraversion will be negatively related to daily positive affect and happiness and positively related to daily negative affect.

Psychological resiliency and wellbeing

Psychological resilience can be defined as the ability and power of individuals to recover rapidly from severe psychological adversities and strains without serious and long-lasting harms to wellbeing (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2013; Wagnild and Young, 1993). By definition, psychological resiliency is positively linked with wellbeing. Numerous studies support this link with evidence (e.g., Mayordomo et al., 2016). Psychological resilience is positively linked with life satisfaction and negatively related to depression (Mak, Ng & Wong, 2011); higher general health perception, job satisfaction, and lower levels of exhaustion and physical illness (Pretsch, Flunger & Schmitt 2012). Individuals experience life events that can be highly stressful and traumatic during the pandemic. People experience or witness others losing their jobs, lives, and loved ones all around the world. Just hearing thousands of people dying in a day due to COVID-19 is traumatic itself. We propose that resiliency will be a strong determinant of how such life events affect individuals and we take psychological resiliency as a control variable into our analysis with general levels of physical activity, socializing, online gaming, and happiness.

Method

Sample Procedure and Measure

Respondents were selected via a convenience sampling approach and connected through digital channels given the circumstances of the pandemic. All data were collected through online forms. Respondents who were under high school age (14), who did not provide one complete person level or five complete day level (consecutive) data, who were diagnosed with Covid -19 during the data collection process were excluded. Only respondents with consent and willingness to participate and living in Turkey were included. Convenience sampling was used in this process. Participants were informed about the procedure, and the nature of the study, and they filled daily forms for five consecutive days and the longer person-level questionnaire one week after they finished the daily phase. 390 participants provided one person-level and five day-level responses each. Analyses were conducted with 1950 day-level and 390 person-level data. Responses were matched via a code provided by the participants in each form. No personal information was asked, and all participants were volunteers.

We measured daily positive and negative affect, daily happiness, daily time spent for exercise, daily time spent on digital games, and daily time spent for socializing for five consecutive days with a short form. Data regarding general happiness, extraversion, psychological resiliency, time spent on digital socializing, gaming, and exercising in general, total time spent at home from the beginning of the pandemic, number of people living at home, the nature of change in the household income and demographics were measured with a lengthier survey delivered one time one week after the daily surveys.

We used The Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) developed by Watson, Clark, and Tellegen (1988) and adapted to Turkish by Gençöz (2000). To assess daily negative and positive affect levels of participants, the wording in the instructions of the scale was modified slightly for asking the frequency of the relevant emotions experienced on that day. We used three items for positive affect ‘enthusiastic', ‘strong', ‘active'; and four items for negative affect ‘nervous', ‘upset', ‘distressed', and ‘irritable'. We selected these items for three reasons; first, we wanted to keep the daily questionnaire (one delivered five days) short and less demanding for participants to increase the response rate and usable data. Second, these items were more suitable for asking day-level experiences. Last, they were the most relevant ones for the aim of the study and the conditions entailed by the pandemic.

The Happiness Scale developed by Demirci & Ekşi (2018) was used for assessing the daily happiness levels of participants. The authors provided high validity and reliability for the scale, which has a one-factor structure and consists of 6 items. We used all six items in both forms (daily and person-level), and small modifications were made on the wording of the items and instructions for converting it to a daily measure.

Items of the 5-factor Personality Inventory developed by John, Donahue & Kentle (1991) and adapted to Turkish by Sümer, Lajunen, & Özkan (2005) are used for assessing extraversion levels of respondents. All items of the scale assessing extraversion were utilized in the person-level form.

To determine the psychological resilience levels of respondents, the measure developed by Friborg et al. (2003) was used. The scale was validated for Turkish by Basim & Çetin (2011).

Asking the frequency of the behavior or the time spent for such activity is frequently used in several studies that are addressing socialization, gaming, and physical activity (e.g., Fuligni, & Hardway, 2006; Hellström et al., 2012; Przybylski, 2014; Männikkö, Billieux, & Kääriäinen; 2015; Mills et al., 2018). Daily time spent for exercise, digital gaming, and digital socializing were assessed via asking single item open-ended questions asking the time respondents spent for such activities. Likely, we asked how much time respondents spent at home in total because of the pandemic, and the number of people living at home was asked with single questions. The nature of change in the household income due to pandemic was asked by simply asking a categorical question with options ranging from ‘it decreased a lot' to ‘it increased a lot'. Gender, level of education, and marital status were asked with categorical questions. Age was asked as an open-ended question.

60% of the respondents were female, 69% were single, and 61% of the respondents were university graduates, 27% of them were high school graduates. The average age was 29 ranging from 14 to 85. Participants were under lockdown at home for an average of 25 days. 4,5 people were on average were living in the houses of the respondents. 47% indicated that their household income was decreased due to the pandemic. 10% answered as their income decreased drastically and 39% responded no change, and 3% indicated an increase in their household income.

Analysis

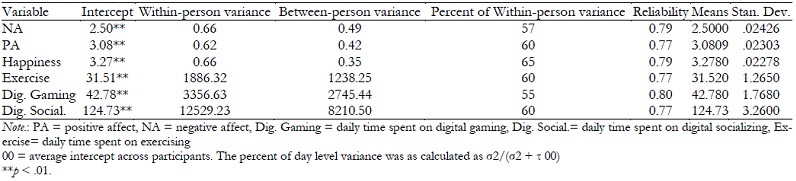

We adopted a multilevel analysis approach where days were nested in individuals. Hypotheses were tested using hierarchical Multiple Linear Modeling via HLM statistical program (Raudenbush, Bryk & Congdon, 2011) HLM 7.00 for Windows. Prior to the tests for our hypotheses, we partitioned the within-person variance with total variance (between-person variance plus within-person variance) for testing the properness of using a multilevel approach. Results showed that significant amounts (57% to 65% see table 1) of the total variance for daily measured variables were level 1 (within-person) variance, and this is an indicator of the necessity for using multilevel approaches.

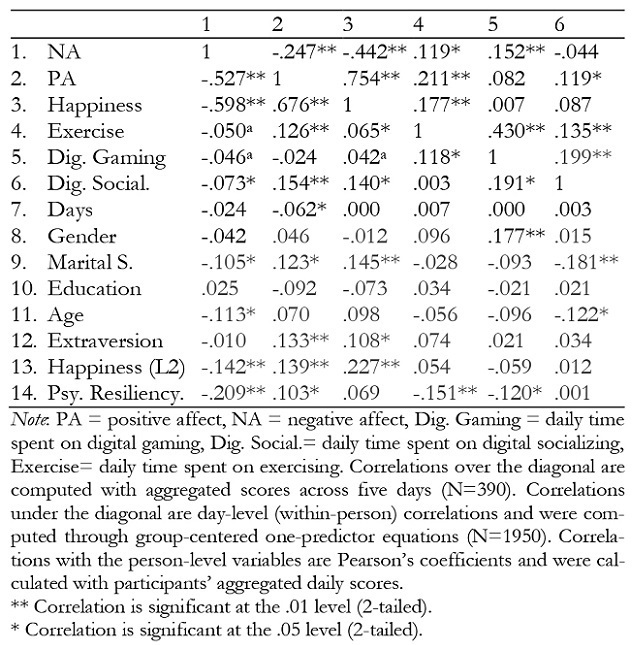

Prior to hypothesis testing, we calculated the zero-order relationships between variables. Correlations were computed at different levels and across different levels via two methods. All daily variables were aggregated to their means across days for each person, and these scores were used for calculating the correlations among day-level and person-level variables. This is like the conventional method, but just asking some variables for five days (and taking their means) instead of asking them once. The other method was designed for taking both variance levels into account and calculating the associations with a multilevel approach via using variance difference scores produced in HLM.

Scores provide preliminary support for the propositions of the study. Daily exercise, digital gaming, and digital socializing demonstrate significant associations with the dependent variables of the study. Aggregated scores and multilevel scores for NA, PA, and Happiness together provide significant links with exercise, digital gaming, and digital socializing. Extraversion, general happiness, and psychological resiliency demonstrated significant associations with the study variables. Associations will be tested further through multilevel analysis.

We created multilevel random coefficient models for testing the study hypothesis with day-level and person-level variables. Control variables, age, gender, education, total time spent home under lockdown, change in household income, number of people living at home demonstrated no significant relationship with any of the dependent variables; thus, they were excluded from the table for simplicity. Marital status showed significant relations with dependent variables. Being married was linked with higher levels of happiness, positive affect, and lower levels of negative affect.

Results indicate significant relations between daily exercise and daily digital socializing with all three of the dependent variables in the way that was proposed by the study. Thus, hypotheses 1 and 2 are fully supported. On the days respondents spend more time exercising and digital socializing, they experienced higher levels of happiness and positive affect and lower levels of negative affect. Day-level digital gaming showed no significant association with any of the dependent variables. Hypothesis 3 is not supported. The general level of digital gaming showed a positive relationship with NA.

The level of extraversion was positively associated with NA as proposed by the hypothesis 4. Extravert participants were more negatively affected by the circumstances brought by the pandemic. Extraversion level was significantly and positively related to NA (est= 0.20 and t = 3.20). Psychological resiliency was negatively associated with NA. Results provided no evidence for significant relationships between Extraversion and Psychological resiliency with PA and Happiness. In conclusion, hypotheses 1 and 2 are fully supported, hypothesis 4 is partly supported, and hypothesis 3 is not supported.

Discussion and Conclusion

The study aimed to investigate the effects of physical exercise, digital socializing, and digital gaming on happiness and positive and negative affect levels of individuals. The data collection period was the first week of May 2020, where there were strict rules for staying at home for age groups 20 and younger and 65 and older. There were lockdowns on weekends and holidays for everyone except some working groups (e.g., health care professionals). Besides, all places for any kind of group meetings (seaside, shopping malls, diners, restaurants, cafes, gyms, etc.) were closed. Travel restrictions forbade intercity travels. There were strong campaigns such as “stay home” or “life fits at home” advising people to stay home. Education was transferred online. Most organizations supported online and distance working.

Considering the dynamic nature of the pandemic and people's reactions to it, we assumed a significant within-individual variance in the variables and designed a multilevel research model. Results of the preliminary analysis supported our assumption and the significance of using multilevel analysis. Findings supported the proposed relationships regarding day-level physical activity at home and digital socializing. They both increased the levels of day-level positive affect and happiness and decreased negative affect. On the other hand, daily online gaming did not relate significantly to any of the dependent variables. Studies that addressed the link between physical activity and psychological wellbeing during the pandemic support our findings (Maugeri et al., 2020).

Some findings in the literature regarding the outcomes of gaming demonstrate a positive nature (e.g., Jones et al., 2014; Kutner & Olson 2009), while some describe a negative one (e.g., Wang, Sheng, & Wang, 2019; Ivory, Ivory, & Lanier, 2017). The balance and excessiveness in the amount of time spent on gaming can be determinative on these conflicting findings. Several studies investigating gaming and wellbeing association indicate a curvilinear (U-shaped) relationship (e.g., Allahverdipour et al., 2010; Yamaguchi, 2020). We tested if there is a bending point for this link through a series of regression analyses. Results demonstrated no significant quadratic relationship. As mentioned earlier in the paper, the factors brought by the pandemic are unique, and even highly established associations are re-explored under these circumstances. One example from the current study is the positive link between extraversion and negative affect, which is contrary to the general stream of findings on this matter (e.g., Gale et al., 2013; Vittersø & Nilsen, 2002). Introverts are less affected by the lockdown and social distancing as they are more likely to consider these conditions as their normal. Socializing and companionship of others are more indispensable and habitual for extroverts.

In conclusion, daily physical exercise and digital socializing can help to mitigate the adverse psychological effects of the pandemic by increasing PA and happiness levels and decreasing NA levels. Social distancing constitutes an effective measure in the pandemic process, and it reduces social interaction, which plays an important role in dealing with the negative psychological outcomes of the pandemic, boosting the loneliness levels that will increase these negative outcomes (Van Bavel et al., 2020). During this unique and challenging time, socializing through online channels and physical activity at home stands as simple and effective ways to cope with the negative psychological outcomes of the pandemic. Excuses for inactivity are mostly intrinsic (Nahas, Goldfine, & Collins, 2003), and people can exercise everywhere, even by using their own body weight when there is no equipment. It is never the same with face-to-face communication but still, findings indicate that digital socializing can demonstrate the same nature and pattern of relationship (Coget, Yamauchi & Suman 2002). Policymakers can alter the wellbeing levels of individuals by advising physical activity and online socializing through public broadcasts, social campaigns, and awareness-building programs that are informing individuals on how to deal with the pandemic.

Although daily multilevel research design enabled us to explain the intra-individual and inter-individual variance, due to the difficulties in collecting daily data, we preferred to use shorter forms to make it easier for respondents to follow up for five consecutive days. More comprehensive analysis (that requires longer forms) on the type and content of gaming can enhance our understanding of the daily consequences of online gaming. Motivation to play can affect the outcomes of gaming more than the time spent on the activity (Hellström et al., 2012). Cultural characteristics can also affect the links between gaming and its possible consequences (Cheng, Cheung, & Wang, 2018). Comparative studies addressing the pandemic period can expand the knowledge on the matter. Readers should keep in mind that the data collection period entailed unique circumstances due to the pandemic. Considering the dynamic nature of the conditions brought by the pandemic, studies targeting longer periods and different phases of the pandemic can further explain the relationships among study variables and provide more generalizable outcomes.