Introduction

Current educational systems face the challenge of becoming inclusive schools that facilitate and act to improve/opt for quality education without exclusion. This involves the transformation of the whole educational system and requires active and participative involvement of all the community. The success of the processes of inclusion depends on several factors, including the level of empowerment of the educational community in the process (Sandoval, 2009). The perception of the members of the educational community will depend on the inclusion measures, strategies and procedures that are in place to make it effective.

To a great extent the body of research aimed at evaluating attitudes towards disability has focused on knowing the views of the teachers and highlighting the variables that are linked to favourable or unfavourable opinions (Chiner, 2011; Dengra, Duran & Verdugo, 1991; Garcia & Alonso, 1985; León, 1995; Martin & Soto, 2001; Parasuram, 2006; Shannon, Tansey & Schoen, 2009; Soto, 2007; Stauble, 2009). In a review of teachers' attitudes towards disability, among the variables that have generated most interest we found gender, age, years of experience, contact with pupils with special educational needs (SEN) and training acquired at different educational stages (Chiner, 2011; Garcia & Alonso, 1985; León, 1995).

Regarding gender the results have been rather inconsistent. While some studies claim that women teachers have a higher tolerance towards inclusion (Eichinger, Rizzo & Sirotnik, 1991), others have found no differences in terms of this variable (Galović, Brojčin & Glumbić, 2015; Garcia & Alonso, 1985; Parasuram, 2006; Sánchez, 2011). Abós and Polaino (1986) published a paper in which reference was made to several factors having a bearing on school integration. Their results highlighted that a variable that influenced the attitudes of teachers is gender; and that men expressed more favourable views than women to the idea of integration.

Regarding teachers' age, Dengra et al. (1991) and Garcia and Alonso (1995) concluded that the variable of age and time spent teaching negatively correlated with positive attitudes towards students with SEN. Thus, Parasuram (2006) showed that teachers with less than five years of teaching experience had more positive attitudes.

When the variable is the experience of contact with students with SEN, research suggests that teachers who have had more opportunities to work with these students have a more favourable attitude towards inclusion. Previous contact with students with SEN promotes the development of positive attitudes (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; Parasuram, 2006; Rodriguez-Martin & Alvarez, 2015). In the Spanish educational context, Aldea (1993) points out that teachers working with students with SEN are more in agreement with their inclusion that those who have not had that experience.

Another important factor in assessing the attitudes of teachers towards inclusive education is the knowledge they have on SEN. Work has been done that has shown that information about disability throughout their university education could be one of the determinants of attitudes (Carberry, Waxman & McKain, 1981; León, 1995), further proving that the greater the level of information and training the more positive the attitudes (Garcia & Alonso, 1985; Mestre, Guil, Marcilla, Aguilar & Gonzalez, 1996; Verdugo, Jenaro & Arias, 2002). Diaz, Carballo and Jimenez (2006) noted that a large number of teachers considered the training they received during the degree course either non-existent or bad. A fruitful line of work on the attitudes of physical education teachers has been highlighted by various authors (Gonzalez de la Cruz, 2000; Hernandez, 1998, 1999; Hernandez, Casamort, Bofill, Niort & Blazquez, 2011; Torres, 2010). Studies in both primary and secondary education show that a high percentage of physical education teachers do not treat diversity as reflected in the law. One of their main arguments (Mendoza, 2009) is their lack of knowledge and so to avoid making mistakes in their work they do not participate at all.

Teacher training has been identified as a major contributor to the attitudes of the teacher (Stauble, 2009). In this way, a wide field of study has been the analysis of the attitudes of teachers and future teachers at different educational levels. Overall, they found no significant differences in the attitudes of teachers depending on the educational stage (Chiner, 2011).

At the university level there have been several studies (Comes, Parera, Vedriel & Vives, 2011; Martinez & Bilbao, 2011; Mayo, 2012; Rodriguez-Martin & Alvarez, 2015; Sánchez, 2011; Soto, 2007). Martinez and Bilbao (2011) conducted a study in order to understand the attitudes of the teachers of the University of Burgos towards people with disabilities taking into account the impact of socio-demographic variables gender, centre, years of experience, contact with persons with disabilities and experience in educational integration. The results showed that attitudes are one of the main elements that may facilitate or hinder the process of inclusion of students with disabilities in higher education and knowledge of such attitudes can help promote a change of attitude so that Spanish universities are able to reflect a positive vision of people with disabilities, with their possibilities, potentials, capabilities, and rights and freedoms comparable to those of other people.

Likewise, Mayo (2012) analysed the attitudes of university teachers of the University of Santiago de Compostela towards students with disabilities and how this integration affects their teaching practice, pointing to the need to increase teacher training regarding disability in order to reduce levels of teacher unease, and provide quality education to this group of students. Comes et al. (2011) came to similar conclusions in Roviara i Virgili University, noting the importance of having information / training on disability and how to serve their students with disabilities before giving their classes.

In a large study at the University of Almería, Sánchez (2011) analysed the educational and social integration of students with special needs associated with a disability from the perspectives of teaching and research staff, administrative staff, students in general and students with disabilities. The teaching and research staff showed a good acceptance of the integration of students with disabilities in college, regardless of the centre, although it was noted that the lowest level corresponded to the centres for Health, and the highest to Education. No significant gender differences were found. In addition, it became clear that integration is favoured by the fact of having received information about students with disabilities.

Recently, and similarly, Rodriguez-Martin and Alvarez (2015), in a study that sought to identify the attitudes of a sample of university teachers and students and the inclusion of students with disabilities in the university have found discrepancies in the action of teachers according to gender and branch of knowledge. Garabal-Barbeira (2015) analysed the attitudes of students and teachers towards students with disabilities at the University of A Coruña, Spain. Most teachers reflected that they are not trained to meet the needs of students with disabilities.

As is clear from the literature therefore, that it is in the field of attitudes towards disability that the role of the professional involved is of utmost importance because the way the teacher responds is critical to transforming education. Thus our interest focuses on addressing this issue from a socio-educational perspective, allowing us first to look into the ideas, beliefs and attitudes of teachers of the Faculty of Educational Sciences (FES) of the University of Granada (UGR) towards students with SEN, and secondly, to analyse the influence that the variables of gender, age, years of teaching experience, contact and information have on those attitudes. This is the axis that guides this research article to the extent that the attitudes of teachers towards including students is a powerful predictor of the quality of education for the inclusion of students with disabilities (Cook, Tankersley, Cook & Landrum, 2000).

Method

Design and Participants

The teaching and research staff of the FES department in the University of Granada, comprises around 401 members (Academic Report of the Faculty of Education Sciences, 2018), teaching in building 248. 82 teachers have participated in the study. Table 1 sets out the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample. See Table 1.

Procedure

This study is part of a broader investigation that is being developed at the University of Granada. The questionnaire was used as a tool for gathering information for the research. It had support staff, but the training, preparation and management of the tests, was carried out by teachers of the FES. The activity was offered to all teachers of the Faculty on a voluntary basis. The collection of information was conducted during the months of January to June, in the mornings and afternoons, individually and anonymously. The time spent on its completion was 45-60 minutes. In the different applications the objectives of the investigation were explained to the participants so that they could provide comments and suggestions they deemed appropriate. After collecting these data they were digitalized for further statistical analysis. The answers given were included in a database and analysed using SPSS 25.0.

Instruments

Data collection was conducted through two questionnaires:

The Scale of Attitudes towards People with Disabilities (Verdugo et al., 2002), a multidimensional scale (consisting of 37 items) developed in Spain, with studies of reliability (Cronbach's alpha .92) and validity (one general and the other specific for physical, sensory and mental impairment). The task to be performed by the respondent is to say whether they agree or disagree with each of the sentences presented, either positively or negatively, with the meanings and scores of the following opinions: I strongly agree (MA) (1); I quite agree (BA) (2); I partially agree (PA) (3); I partially disagree (PD) (4); I mainly disagree (BD) (5); I totally disagree (TD) (6). The answers close to 1 are those that indicate the more favourable attitudes. The factorial analysis of the scale revealed the existence of five factors: evaluation of capabilities and limitations, recognition / denial of rights, personal involvement, generic rating, and Assumption of roles. In addition to the items listed in the scale other were added relating to age, gender, education and profession of the participants. Items relating to contact with disabled people were also included, specifically they were asked whether they had had contact or not with the disabled and, if so, its frequency (almost permanent, habitual, frequent or sporadic) and the type of disability presented by the person with whom they had had contact (motor, auditory, visual, intellectual or multiple).

The questionnaire on Ideas and attitudes on skills, training and professional development that teachers at the University of Almeria gave to the group of students with special needs associated with a disability (Research group on Diversity, Disability and Special Educational Needs), consisted of 40 items. The structure was presented on a Likert scale, with four possible answers: 1. Strongly disagree; 2. Disagree; 3. Agree; 4. Strongly agree. Thus the custom or predisposition to locate the central response as the most appropriate scale and therefore less committed is avoided. All questions are closed except the last, which in each questionnaire appears open to the formulation and observations the respondent wishes to make.

In order to ensure the quality of the instruments and reduce the possible errors associated with them, the construction of the questionnaire followed a thoughtful process, prepared in accordance with the guidance of some experts in this area. Once the first version was produced, it was put to the trial of education experts. Subsequently, a pilot study was carried out, applying to students of the same university, in order to ensure the suitability of the object of study and the understanding of the questions. Following the analysis of the pilot study, in which the wording of some questions was modified and others were removed, because they were repetitive and/or not providing relevant information, the final versions were obtained (Sánchez, et al., 2009).

Results

We shall now present the results obtained after performing a statistical analysis of data. In the first place, a descriptive analysis of the ideas and beliefs of teachers was carried out, taking into account the percentage of teachers who had students with disabilities and what type they were. Subsequently, a descriptive analysis of attitudes was made to relate different variables such as gender, age, contact and information received on the subject of disability.

Ideas and beliefs of teachers

Out of a total of 82 teachers from the UGR who completed the questionnaire on Ideas and attitudes on skills, training and professional development (Research Group GI Diversity, Disability and Needs Special education), 75 said they have had students with disabilities in their class (91.5%), compared to 7 who said they had never had any (8.5%). Of those teachers who said they had, 2.4% indicated that the disability was physical, 1.2% stated that it was psychic, 20.7% said it was auditory, 7.3% visual, and 58.5% highlighted that the students with disabilities they had taught had various types of disabilities.

Looking at the data in the descriptive analysis of the ideas and beliefs of teachers (Table 2), we see that they agree that access of students with disabilities to the University should be facilitated (M = 3.85, SD = .448) and that is the task of all personnel involved in universities to help their proper integration (M = 3.78, SD = .498). However, they feel that training courses to facilitate these students' learning (M = 3.41, SD = .831) are necessary, and that there should be greater coordination among teachers in this regard (M = 3.52, SD = .689). They also thought it desirable that teachers were informed beforehand that they would have students with disabilities in their subjects (M = 3.56, SD = .704) and advising them (M = 3.70, SD = .560); because they believed that teachers did not have sufficient resources to achieve successful integration of students with disabilities at the University (M = 1.77, SD = .708). Moreover they had no knowledge of how other universities integrated of such students (M = 1.93, SD = .086). They think, therefore, that there must be a central unit to coordinate and advise disabled students and teachers involved in their training (M = 3.78, SD = .498).

Teacher attitudes

Table 3 shows the mean scores of the factors analysed under the Scale of Attitudes towards people with disabilities. (Verdugo et al., 2002). In general it can be seen that teachers have quite positive attitudes (M = 2.91, SD = 1.141), and there are small differences between the different factors.

Overall, the degree of agreement among surveyed regarding their conception of persons with disabilities, their learning ability and performance, and inferences about skills (M = 2.14; SD = 1.018,) is noteworthy. So far as recognition / denial of rights is concerned, the assessments regarding the recognition of fundamental rights of the person (e.g. equal opportunities, right to vote, access to credit, etc.) were on analysed and, in particular, the right towards normalization and social integration, demonstrated positive attitudes (M = 2.66, SD = 1.063).

Block III deals with personal involvement, in which judgments relating to specific interaction behaviours that the person would take effect in relation to persons with disabilities. This revealed, as reflected through measures close to 3.20, that teachers have a fairly favourable predisposition to act and showed an effective acceptance of persons with disabilities in social, personal and work situations. Factor IV, generic rating, sets out overall views and general qualifications that respondents made about the allegedly defining features of the personality or behavior of people with disabilities, not appreciating ratings that denote negative or pejorative stereotyped labelling applied to persons with disabilities (M = 3.75, SD = 1.612). Finally in the section on Assumption of roles the respondent made assumptions about the conception of themselves as people with disabilities with very similar scores in the responses given (M = 2.82, SD = 1.218).

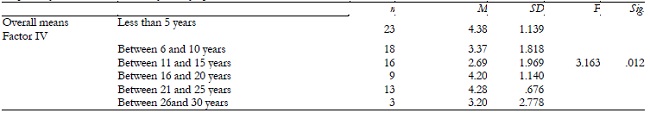

After performing the descriptive analysis of the different factors that make up the scale, a multivariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to analyse the effects of the variables that gender, age, years of teaching experience and contact have on the different factors that make the scale of attitudes towards disability (Factor I. Evaluation of the capabilities and limitations, Factor II Recognition / Denial of rights. Factor III Personal involvement; Factor IV generic rating; Factor V. Assumption of roles), also showing means and standard deviations by titration. Of the different variables analysed no significant differences were found when taking into consideration gender (F (1, 80) = 1.47, p < .228), age (F (4, 77) = 1.24, p < .300), contact with people with disabilities (F (1. 80) =. 48, p <.487) or information received on this subject (F (2, 79) =. 20, p < .813). However differences were found in respect of years of experience of Factor IV, with teachers from 11 to 15 years of experience being more likely to assign features or specific behaviours to students with disabilities (F (5, 76) = 3.16, p <.012).

Discussion and conclusions

Aware that inclusion in higher education has seen significant progress in recent years (Bilbao, 2010; Comes et al, 2011), surprisingly there are not many studies that focus on the educational stage that is the objective of this research, which analyses the ideas, beliefs and attitudes of teachers of Faculty of Educational Sciences at the University of Granada. It is important to know the perception of this group since it significantly affects the way to meet the educational needs of all students. This study allows us to find that in general the ideas, beliefs and attitudes towards disability, by teachers of the UGR, are quite positive.

The teacher's role is key because the attitude and expectations shown to students with SEN, positively or negatively, affect their self-esteem, motivation and learning (Sales, Moliner & Sachis, 2001). Therefore, we observe the need to develop positive attitudes towards diversity and inclusion of students from initial teacher training as part of the curriculum or through additional training, sensitizing the future teacher to the importance of their beliefs to the heterogeneity of students and how they influence their present and future performance, behaviour and development (Reina, 2003; Sales et al., 2001; Sanchez, Diaz, Sanhueza, & Friz, 2008). Since inclusion is an attitude that affects many people, they must be informed, sensitized and committed (Arnaiz, 2005) with the objective that it is carried out in different areas, such as functional, physical, social and educational (Soto, 2007). Thus, university teachers have not only to be excellent in the transmission of knowledge, but should also encourage the development of values, attitudes and interests that help all students to develop, both personally and professionally in his or her life. This requires proper coordination and the acquisition of cooperative strategies among the entire educational community (Sandoval, 2009).

The study of the ideas and beliefs of teachers reveals that this training is necessary because (as found in this research) teachers are not educated to give an adequate response to students with disabilities, it being necessary to make it possible for teachers to address their functions related to attention to diversity, understanding and promoting organizational and curricular changes that are required by inclusive education (Sales, 2006). The knowledge that teachers have about disability is quite poor, there is not enough information about it (Cook, Cameron & Tankersley, 2007; Soto, 2007), a fact that the data presented here corroborates, as well as the study of Méndez and Mendoza (2011), who claim that 76% of teachers considered it appropriate to be given specific training. The lack of preparation, resources and time to face a student with a disability (Alemany & Villuendas, 2004) is obvious. In addition, Suriá (2011) indicates that most centres lack resources and tools appropriate for students who have a disability (Torres, 2010), as supported by the teachers in the present study, which indicated that they did not have sufficient resources to achieve successful integration of students with disabilities at the University.

Today, virtually all Spanish universities have specific support services for these students. Some of the functions they perform are giving information, fostering, advice and personalized attention, study support, the removal of architectural barriers, pedagogical and curricular changes, adaptation assessments, awareness of the university community, coordination with other agencies and institutions related, among others (Alcantud, Avila & Asensi, 2000). Nevertheless, more training and information for teachers, who do not have them require a protocol for performance to intervene with students with disabilities (Bilbao, 2010), considering it a necessary step to address diversity (Vieira & Ferreira, 2011).

The descriptive analysis of the effects that certain variables have on the attitudes of teachers, allow us to find that these conclusions apply to teachers regardless of their gender, although this is controversial, since while Alemany and Villuendas (2004) did find that men have more favourable attitudes than women to educational integration, studies like that of Avramidis and Norwich (2002) noted that women teachers are those with greater tolerance and predisposition towards these students, in turn showing greater sensitivity towards integration (Bilbao, 2010). Although the data here provide no significant differences in relation to gender or age (confirmed in other studies such as that of Bilbao, 2010), authors like Leon and Avargues (2007) find that younger teachers are more tense when they have students with disabilities in their classrooms, while there is research indicating just the opposite, that the younger teachers have more favourable attitudes towards integration (Parasuram, 2006; Suriá, 2011). In general, regardless of the age or gender of teachers, many show a great ignorance of experiences of integrating students with disabilities at the university, as in the present study and in that conducted at the University of Almería by Sanchez (2011).

Professional experience is the variable related with age, which according to the data obtained has an effect. Thus, when there is a better knowledge of these students, there is a greater guarantee of success in the process of teaching and learning, having had a greater chance of contacting students who are subject to a disability (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002). Several studies support this fact, noting that teachers who have not had direct contact with people with disabilities have more rejecting attitudes than those who have dealt with this group (Gómez & Infante, 2004; Polo, Fernandez & Diaz, 2010), although contact is not itself guaranteed to create favourable attitudes and express training is necessary.

If contact with people with disabilities, information and prior training acquire a key value, it will then require the effective development of the proposals set out in the social dimension of the European Higher Education Area, an issue that can and must respond specifically through action plans for students with disabilities at each university (Cayo, 2008 quoted in Rodriguez-Martin & Alvarez, 2015). It is necessary that teachers feel prepared to respond efficiently to the diversity of their classrooms, promoting favourable attitudes, through the services and resources that the educational system provides, developing campaigns for raising awareness and promoting tutorial action plans (Rodriguez-Martin & Alvarez, 2015), with the aim of developing the full potential of their students on equal opportunities (Sales et al., 2001).

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.