Introduction

Assessing the occurrence of child sexual abuse (hereinafter, CSA) is one of the most complex tasks faced by forensic psychology. In most cases, there are usually no eyewitnesses, the culprit does not confess, nor is there any medical or physical evidence to objectify these crimes (Manzanero & Muñoz, 2011; Massip & Garrido, 2007), which leaves the child's account as the only evidence of abuse. Although most of the allegations are true, we cannot deny the existence of false reports (O’Donohue et al., 2018; Ruiz Tejedor, 2017) whether intentional or not. This leaves expert evidence as one of the key elements within the judicial process (Martínez et al., 2018), which could explain the high agreement between the conclusions of the forensic psychologist and the judicial pronouncement. For example, in the work of Ruiz Tejedor (2017), a concordance of 88.2% was detected.

To address the assessment of testimony credibility, forensic psychology has used different approaches. For example, it is very common to evaluate the presence of psychological symptomatology as an indicator of the presence of sexual abuse (Pereda & Arch, 2012). The problem of using psychological symptoms as an indicator CSA is that they are usually not qualitatively different from those that a child would present in other situations, such as the divorce of their parents (Scott et al., 2014). This becomes more important when the family that files a CSA complaint is separated, making it difficult to discriminate whether the psychopathology detected is due to the divorce or possible sexual abuse.

Efforts have been made to look for specific symptoms of CSA such as seductive behavior toward the adult, the presence of sexualized games, or sexual knowledge inappropriate to the age of the minor (Baita & Moreno, 2015). However, as the authors themselves indicate, these behaviors can also occur for other reasons, which reinforces criticism of the use of these symptoms as credibility indicators of CSA (Bridges et al., 2009; Poole & Wolfe, 2009; Scott et al., 2014).

In contrast, Pereda and Arch (2012) found that one of the most frequently used methodologies, especially in Europe, is the analysis of the minors' statements, and the Statement Validity Assessment (SVA) is the preferred protocol for this purpose. This instrument, developed in 1989 by Steller and Köhnken, consists of 3 parts: the semi-structured interview with the minor; the Criterial-Based Content Analysis (CBCA), and a list of 12 validity criteria (Köhnken, 2004; Steller & Köhnken, 1989).

The SVA and, specifically, the CBCA, arises from the hypothesis of Undeutsch (1967) who stated that minors' reports have differentiating characteristics when they relate a directly experienced episode and an invented, fabulated, or induced episode (Amado et al., 2015). Although this methodology has an underlying theoretical framework, it has strong detractors. As Manzanero and Muñoz (2011) indicate, some studies have shown higher than acceptable error rates (around 30%). On another hand, other authors such as Vrij (2014) qualify that, although the error rates are high, when the decision is left to the "intuitions" of judges and juries, the error rates are higher. One of the problems of this protocol is its misuse because, in many cases, its application is limited to the criteria of the CBCA, without applying the SVA in its entirety (Köhnken et al., 2015; González & Manzanero, 2018).

Another approach that is attracting a great deal of interest is the protocolized forensic interview, such as the Forensic Interview Protocol (Lamb et al., 2007) developed by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). This interview was created to increase the quantity and improve the quality of the information that is extracted directly from interviews with the minors. In this way, the interviewers ask more open-ended and fewer suggestive questions while obtaining a greater amount of information (Benia et al., 2015).

Likewise, the need to include multiple approaches and aspects in the assessments of testimony credibility is becoming increasingly evident. In this line, the Holistic Model for the Evaluation of the Testimony or HELPT protocol (González & Manzanero, 2018; Manzanero & González, 2015 ) was developed, which seeks not only to assess the minor's declaration but also other factors such as the ability to testify and factors that can influence the declaration.

Following this holistic approach, we consider the possibility of including in the evaluation process other aspects external to the child's statement, such as the characteristics of the child victims of CSA, their families, and the abuse itself.

When examining the characteristics of CSA in the literature, we find that the aggressors are usually male (Aydin et al., 2015; Cortés Arboleda et al., 2011; González-García & Carrasco, 2016; López, et al., 1995; Vázquez, 2004) and that the vast majority are known to the victim (Aydin et al., 2015; Cortés Arboleda et al., 2011; González-García & Carrasco, 2016; López et al., 1995; Trocmé & Tourigny, 2000).

Approximately half of the cases of CSA are intrafamilial although there is a wide variability depending on the study (7% in López et al., 1995; 68.2% in Juárez López, 2002). Two relatively recent studies from Spain found, respectively, 47.5% (González-García & Carrasco, 2016) and 52.8% (Cortés Arboleda et al., 2011) of intrafamilial abuse.

Within the family environment, some national studies show that the biological father is not usually the most common aggressor (1% in López et al., 1995; 5.9% in Cortés Arboleda et al., 2011; and 9% in González-García & Carrasco, 2016) compared to studies from other countries (23.4% in Carlstedt et al., 2009; 30.9% in Shevlin et al., 2018; and 33.76% in Trocmé & Tourigny, 2000).

As for the minors' characteristics, it was found that most of the victims are girls, as stated in the existing prevalence studies, both international (Barth et al., 2014; Stoltenborgh et al., 2015; Stoltenborgh et al., 2011) and national (Benavente et al., 2016; Pereda et al., 2009).

Most of the minors show reactive symptoms, presenting emotional, behavioral, school, and sexual alterations. Behaviors such as attitudes of submission, aggressive behaviors, distrust, low school performance, regressive behaviors, or suicidal ideation, among others, have been described in minors (Baita & Moreno, 2015; Zayas, 2017). In the study conducted by González-García and Carrasco (2016), they found that a high percentage of children who had suffered sexual abuse presented behavioral (75.8%) and emotional alterations (73.7%) and somewhat less than one half presented sexual alterations (44.4%). This fact is striking because, in many publications (Baita & Moreno, 2015; Berlinerblau, 2016; Hidalgo, 2014; Pérez et al., 2019), sexual alterations in minors are mentioned as an indication of CSA but they are the least common in the study of González-García & Carrasco (2016). Other risk factors that have been detected in minors are the minor's previous victimization, whether or not CSA, or the presence of chronic physical or psychological antecedents (Assink et al., 2019).

As for the form of abuse, it seems that, in most cases, it occurs without violence (in 81.1% of the cases in the study of Cortés Arboleda et al., 2011; in 56.5% in González-García & Carrasco, 2016; or in 93.1% in Aydin et al., 2015), and it tends to be recurrent (Benavente et al., 2016; Cortés Arboleda et al., 2011; González-García & Carrasco, 2016; Shelvin et al., 2018).

As for family characteristics, reconstituted families, the presence of non-direct relatives, drug use, or the presence of domestic violence are risk factors (Zayas, 2017). Likewise, in the recent meta-analysis carried out by Assink et al. (2019), they identified as risk factors the presence of child or partner abuse, psychiatric or medical history in the parents, substance use and abuse, dysfunctional dynamics, or having a stepfather. At the national level, González-García and Carrasco (2016) found that 29.3% of the families presented dysfunctional dynamics and mental health problems, 37.4% presented substance use, and there was a history of abuse in 31.3% of the cases.

As for how to detect cases of CSA, it was found that most cases are detected within the child's family (42.8% of the cases), with the mother being the person who detects these cases the most frequently (27.9%). Next in frequency are the Social Services (16.4%), the police (9.9%), and Protection Services (9.3%) (Díaz & Ruíz, 2005).

Finally, the Reina Sofía Center for the Study of Violence (Vázquez, 2004) detected that 58% of cases are disclosed from the child's spontaneous narration, 39% from witnesses, and only 3% from physical indications. For their part, Gutiérrez et al. (2016) found that, in most cases, the conflict is disclosed from questions by third parties, followed by the child’s spontaneous or premeditated narration. It should also be noted that, in both studies, there is a very high percentage of cases that report or denounce abuses years after they occurred, an aspect that we usually find in the literature (Alaggia et al., 2019).

In conclusion, we found certain common features in child victims of CSA. However, quantitative data are still scarce and often contradictory. Therefore, the general objective of this study, framed within a broader investigation, is to explore the existence of certain psychosocial factors (psychological, socio-family, and abuse-related) that can discriminate between credible and non-credible cases, to complement the expert assessments of testimony credibility in CSA.

Method

Participants

We used an incidental sample of 99 cases of minors involved in penal proceedings for an alleged crime of sexual abuse. These cases were extracted mainly from the archives of the Forensic Medical Clinic and Higher Court of Justice of the Community of Madrid, the Forensic Medical Clinics of the Community of Castilla-León (Valladolid) and Extremadura (Cáceres), as well as the Institute of Legal Medicine of Galicia (A Coruña). The minors' age ranged between 4 and 17 years with a mean age of 11.31 years (SD = 3.92) and 85.9% (n = 87) were girls. The sample was divided according to the expert opinion into Credible (C) and Non-Credible (NC). Group C was composed of 68 cases (M = 11.82 years, SD = 3.37) and group NC of 31 cases (M =10.19 years, SD = 4.79).

Most of the children were Spanish (C: 60.3% and NC: 77.4%), the rest were from a Latin American country (C: 26.5% and NC: 16.1%), another European country (C: 7.4% and NC: 3.2%), Africa (C: 4.4% and NC: 3.2%), or Asia (C: 1.5% and NC: 0%).

The inclusion criteria were that a psychological expert report had been issued by the psychologists assigned to the Justice Administration and that there should be a judicial pronouncement on the case. The exclusion criteria were that minors’ age was below 4 years and that they had no maturational or mental delay. Likewise, those cases in which the SVA could not be applied due to a lack of the minor's free narrative were ruled out.

Instruments

To collect the data and the target variables of the study, we used the Clinical-Expert Assessment Protocol developed by Ruiz-Tejedor et al. (2016) composed of variables that can complement the analysis of testimony credibility in CSA. This protocol includes psychological, socio-family, and criminological variables. The psychologists assigned to Justice Administration evaluated the cases through the SVA protocol, which allowed them to identify in probabilistic terms the testimony credibility of the assessed minor (C vs. NC). We note that the variables collected through this protocol are external and independent of the assessment made by the forensic psychologists in their reports of testimony credibility.

Design

This is a retrospective quasi-experimental study in which the result of the assessment carried out with the SVA was used as a dependent variable, that is, C or NC, depending on the psychological expert report for each of the selected cases. The variables belonging to the assessment protocol developed by Ruiz-Tejedor et al. (2016) composed of psychological, socio-family, and abuse-related indicators, were the independent variables.

Procedure

The cases were collected from the files of the collaborating courts. We obtained the ex profeso permission of the Justice Administration to perform this study, complying with the regulations in force for the protection of personal data. All legal measures on data protection were safeguarded, protecting confidentiality and anonymity at all times. We obtained the informed consent of all the adult participants or guardians from whom data of the reports were extracted and who were also allowed to refuse to be part of the study. A fact sheet on all these points was provided for this purpose.

The expert reports were extracted from the different judicial units at random until the final sample of studies was completed. Psychological, socio-family, and abuse-related information was obtained by downloading the data of all these reports, using the clinical expert protocol described above. The information used in this investigation was collected from the expert reports issued by the psychologists attached to the Justice Administration to avoid possible biases (because by acting ex officio, their experience in the subject, as well as their impartiality in the case, are guaranteed).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and percentages) were used to examine the minors' characteristics. Contingency tables and the chi-square statistic were used to establish mean differences for independent samples (C vs. NC). The chi-square test allowed us to work with samples of unequal size, as this test for independent samples or groups runs with the expected frequencies, from which the frequency distribution of the total cases is obtained. In the case of expected frequencies of less than 5, Fisher's exact statistic was chosen, as such small frequencies can lead to a reduction in statistical power. Finally, the phi coefficient (φ) was chosen as a measure of the effect size. The data were analyzed with the statistical program SPSS 22.0.

Results

Psychological factors associated with credibility

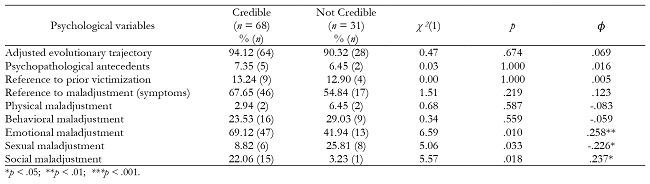

Table 1 shows the psychological characteristics of the minors who reported sexual abuse based on the psychological-expert opinion that was made by the psychologist assigned to Justice Administration.

As can be seen, there are hardly any statistically significant differences depending on the psychological variables, most of which have an adjusted evolutionary trajectory, with no psychopathological antecedents and no victimization prior to the alleged sexual abuse. Although more than half of both groups report the presence of maladjustment of some kind, significant differences were found depending on the symptomatology reported. Specifically, children in group C presented significantly more emotional and social symptoms than those in group NC. Moreover, Group NC claimed to have more sexual imbalances than Group C.

Socio-family factors associated with credibility

Table 2 shows the analyses of various socio-family variables depending on testimony credibility. As shown in this table, more significant differences were found in the socio-family variables examined. First, it was observed that the NC group presented dysfunctional dynamics more frequently, both in the past and at the time of the assessment. At the educational level, there were no differences, although it is noteworthy that more than twice as many families in Group NC had a high level of education compared to Group C.

As for coexistence, the most striking aspect is that no family was in the process of divorce. On another hand, we found that the families of Group C usually had a stable coexistence, the minors lived with both parents (not separated), and the democratic style was the most common educational style. In the NC group, we found a majority of separated parents, minors who lived with their mother (exclusive maternal custody), and the most common educational style was the authoritarian style.

Finally, the presence of litigation between the parents and the need for the intervention of social services was found more frequently in the NC group than in the C group.

Abuse-related factors associated with credibility

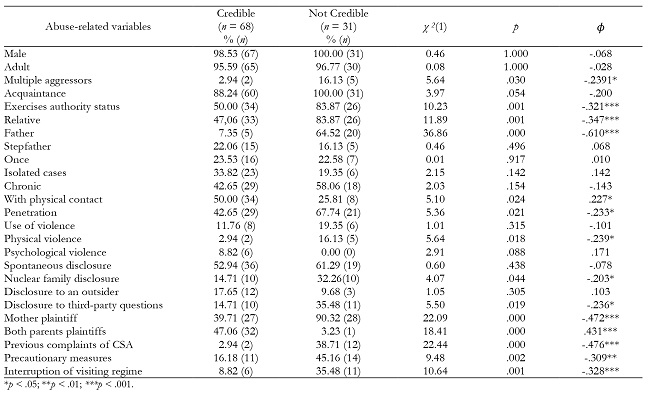

Third, we examined the characteristics related to abuse associated with testimony credibility (Table 3). This category included the characteristics of the alleged sex offenders, how the abuse occurred, and the subsequent judicial process.

Concerning the characteristics of the aggressor, in both groups, the majority of complaints targeted a male of legal age and known to the victim as the perpetrator of the alleged abuse. However, in the NC group, we found a greater presence of complaints about several aggressors (although only in 16.1% of the cases), and a higher percentage of complaints against a family member was clearly observed. Within the family group, in 64.5% of cases in the NC group, a police report was filed against the biological father, compared with 7.4% of cases in Group C.

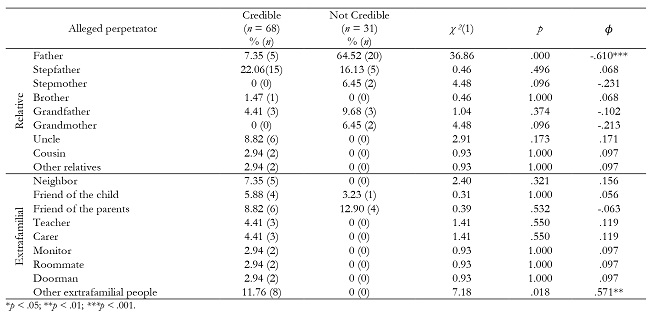

More specifically, Table 4 shows the frequencies and percentages for the reported aggressor. As can be seen, while in Group C, the frequencies were very equally distributed, in the NC group, they accumulate mainly in the figure of the biological father. On another hand, in Group C, we found a higher frequency of complaints against the stepfather, but without any significant differences between the two groups. It is noteworthy there was a greater frequency of perpetrators than of victims because, in seven of the cases, the minors reported more than one aggressor.

Finally, it is significant that, while almost all the cases in Group NC reported a person who exercised some authority (83.9%), in Group C, this only happened in half of the cases (50.0%).

As for the casuistry of the alleged abuses, we only found significant differences in Physical Contact and Penetration, such that Group C tended to report more frequently that the abuses occurred with physical contact whereas Group NC reported the existence of penetration more often.

As for the indicators related to the judicial process, we found that the abuse is disclosed more often in Group NC than in Group C within the nuclear family and following questions from third parties. In addition, complaints filed by the mothers occur more often in the NC group, and complaints by both parents appear almost only in Group C. We also highlight that the NC group had a higher prevalence of previous complaints of child sexual abuse, the adoption of precautionary measures, and the interruption of visits.

Discussion and conclusions

Current research shows that, although the vast majority of complaints filed for alleged CSA are real, there is a considerable percentage of cases in which the abuse had not been committed (O'Donohue et al., 2018). The lack of objective proof, evidence, or witnesses (Manzanero & Muñoz, 2011; Massip & Garrido, 2007) makes it even more difficult to determine whether or not an abuse has occurred. Therefore, the evaluation of testimony credibility in CSA is one of the most complex areas of study of forensic psychology. In this context, the purpose of this study was to carry out a preliminary analysis of those variables that could complement the assessment of testimony credibility in forensic psychological evaluations.

From a global point of view, the first aspect we observed in the results of this study is that there does not seem to be a clear pattern of characteristics in children who have allegedly been abused (classified by ex officio psychologists as credible). Thus, of all the variables analyzed, in Group C (Credible Testimony), we only found a significantly greater presence of the variables: Emotional maladjustment, Social maladjustment, Stable coexistence, Coexistence with both parents, Democratic style, Physical contact, and Complaint by both parents. However, some of these variables are also present in Group NC (Non-Credible Testimony), although with a lower percentage, which would limit the predictive capacity of the presence of these factors. The variables that indicate high credibility are the presence of social maladjustment in the minor, stable coexistence and with both parents, and the complaint being filed by both parents, as there are hardly any cases in the NC group with these variables. In contrast, we found several common psychosocial factors in the complaints that were classified as NC.

Concerning the psychological variables, we found that the simple reference to psychological symptomatology does not seem to discriminate between the two groups, supporting the idea that the predictive capacity of the psychological alterations by themselves cannot be taken as indicators of credibility (Bridges et al., 2009; Poole & Wolfe, 2009; Scott et al., 2014).

However, we did find a greater reference to symptomatology of a sexual nature in the NC group than in the C group. The data of the C group are in line with the results of González-García and Carrasco (2016) or Vázquez (2004), who found that sexual alterations are much less common than emotional or school alterations. Therefore, we could deduce through these results that, when an abuse is reported that very likely has not occurred, there is a tendency to refer to sexual symptomatology, forgetting the social maladjustments, whereas the most common aspect in abused children is the emergence of social, educational, and emotional symptoms but to a lesser degree sexual symptoms. It should be noted that, in this study, there was no high prevalence of maturational delay, psychopathological antecedents, or prior victimization, all risk factors described in the literature (Assink et al., 2019).

Regarding the socio-family variables, divorced parents were more common in the NC group. This result is in line with the arguments of Echeburúa and Guerricaechevarría (2005) when claiming that there are usually higher prevalences of false reports in contentious processes in which minors can be used by one of the parents to obtain custody or to take revenge on the other parent. However, no case was found in which the complaint was filed during the divorce process.

In most cases of the NC group, the mother had sole custody, the family presented dysfunctional antecedents, there was litigation between the parents, and the social services had had to intervene at some point. In contrast, it is noteworthy that there were practically no complaints from any of the groups following a joint custody regime. We hypothesized that this might indicate that this custody regime could be a protective factor not only from suffering abuse but from reporting abuse. However, it is possible that, with this custody regime, no complaints are made because no abuse is detected by the parents.

From this second block of variables, we found that stable coexistence of the parents predicts credibility, as it is practically inexistent in the NC group (9.7%) whereas observable family dysfunctionality, litigation between parents, and social services' intervention predict non-credibility, as there is hardly any presence of these variables in Group C (7.4%, 7.4%, and 8.8%, respectively). These characteristics, such as dysfunctional dynamics or psychopathological antecedents, have been detected as risk factors of CSA (Assink et al., 2019; Zayas, 2017) but, in this study, we found these characteristics more frequently in the NC group.

Finally, among the variables related to abuse, the most striking involve the alleged aggressor. According to most of the research consulted, half of CSA occurs within the family itself (Celik et al., 2018; Cortés Arboleda et al., 2011; González-García & Carrasco, 2016; Juárez López, 2002; Trocmé & Tourigny, 2000) and yet the vast majority of the NC group reported someone in their family (83.9%), especially the biological father, in 64.5% of the cases. In contrast, in Group C, there were only 5 cases (7.4%) in which the biological father of the minor was accused. This is in line with the investigations carried out in our country, in which it has been found that the father is not usually the most frequent perpetrator (Cortés Arboleda et al., 2011; González-García & Carrasco, 2016; López et al., 1995). It is noteworthy that the prevalence of victimizing fathers is higher in international studies (Carlstedt et al., 2009; Shevlin et al., 2018; Trocmé & Tourigny, 2000). This form of abuse might be less common in Spain, or there may still be a cultural barrier against filing a complaint of sexual abuse when it was committed by the child's father.

With regard to the alleged perpetrator of the abuse, as seen in Table 4, we again found no pattern of factors in Group C; the stepfather was accused more frequently, although without significant differences between the two groups. This result is in line with the research conducted by Assink et al. (2019), which finds that the presence of a stepfather is a risk factor for suffering CSA.

Statistically significant differences were also found in the authority status of the aggressor, as it was detected in almost 85% of the cases of the NC group compared to 50% of the C group, a percentage similar to that found in other studies (González-García & Carrasco, 2016).

Concerning the form of abuse, we found hardly any significant differences, and there only seems to be a certain tendency in the NC group to report penetrative abuse, whereas, in Group C, it is more common to report only physical contact without penetration or physical violence. In the literature, it is also common for abuses to occur without physical violence or penetration (Aydin et al., 2015; Cortés Arboleda et al., 2011; González-García & Carrasco, 2016; Vázquez, 2004). However, in this study, the statistical differences between the two groups were not very high, as there were complaints from both groups for both modalities, which would limit their discriminating power.

As for the disclosure, we found that in most cases, it occurs spontaneously in both groups, although in the NC group, it is more common to be disclosed within the nuclear family and as a result of questions from third parties. Concerning the plaintiff, we found that there were hardly any complaints from both parents in the NC group (3.2%), which was the most common form of complaint in Group C. This last group of variables could be a logical consequence of the accused person because, as has been seen, the father is the person most commonly accused in the NC group and, therefore, the mothers' complaints, the adoption of precautionary measures, and the provisional interruption of the visiting regime are more common in order to protect the minor in case of proof of sexual abuse. Finally, it is quite significant that almost 40% of the NC group had previous complaints of CSA, whereas in Group C, we only found 2 cases (2.9%), which is in line with the findings of González-García and Carrasco (2016), where only one of their cases (7.8%) presented previous sexual abuse, but it contradicts the findings of other studies (Assink et al., 2019).

Finally, there are some limitations in this research that should be taken into account. This study is preliminary and is part of a broader investigation dedicated to detecting possible psychosocial factors that discriminate between credible and non-credible cases and that can help to complement forensic psychological assessments. The main limitation is the impossibility of knowing with absolute certainty whether the minors included in each of the groups were adequately classified, which is a great limitation of the scope of the results obtained. However, we currently lack the means to know with a high likelihood whether or not a child has actually been abused due to the lack of external evidence, objective evidence, or witnesses in most cases (Manzanero & Muñoz, 2011; Massip & Garrido, 2007).

On another hand, the sample has some drawbacks as there is a clear inequality in terms of gender because more than 80% of the sample is composed of girls, and Group C is twice as large as Group NC. However, when examining the epidemiological data, we find that abuse is more common in girls (Benavente et al., 2016; Pereda et al., 2009) and that the vast majority are credible (O’Donohue, 2018).

Despite all these difficulties, we believe that more research into this subject is necessary because sexual abuse continues to occur and, every day, the burden of deciding about the credibility of a minor continues to fall on forensic psychologists (Martínez et al., 2018; Ruiz Tejedor, 2017). Given the implications of the expert decision, including that an innocent person could be imprisoned or an abused child could continue to live with their aggressor, we consider it necessary, especially in our country, to carry out more empirical investigations into CSA, despite the complications and limitations involved in its study, with the ultimate aim of protecting these minors as best as possible from a possible revictimization derived both from the occurrence of other abuses and from the multiple explorations to which they are subjected within the judicial process.

text in

text in