Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goal 3 proposed by the United Nations requires to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” (UN, 2016). In achieving this aim, the inclusion of mental health as a key global priority is essential (Izutsu et al., 2015). Particularly, if we consider individuals with severe mental disorders, such as psychosis, which prevalence is very high (Jongsma et al., 2018), and its chronicity and high relapse rates are of concern. Offering psychotic patients, a treatment that contributes to ensure their well-being and health is of utmost importance if we are to make real the SDG 3.

In facing this task, it is particularly important to study successful approaches and interventions to achieve effective therapeutic processes to treat psychosis. Among the approaches that have been presented as important to advance effectiveness, adapting the treatment to each individual and context seems crucial to achieve an optimal recovery (Alanen et al., 2009; Bhaskar et al., 2017). The National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE, 2014) recommends that all individuals diagnosed with psychosis ought to be offered a form of talking therapy. Indeed, enhancing interpersonal and intrapersonal awareness is essential in dealing with an individual’s behaviour (Bergantino, 1977). Fostering patients’ awareness requires establishing a dialogue between therapist and patient. A dialogic approach helps addressing this need since it is based on egalitarian interactions, in which a basic feature is that each participant feels heard and listened accordingly (Bakhtin, 1981). It fosters the co-existence of multiple, separate, and equally valid “voices,” or “points of view, within the treatment (Olson et al., 2014). In this sense, according to a sociocultural view of the mind, thinking is based on an inherent process of appropriating the voices of the socio-cultural environment in which they are situated (Vygotsky, 1979; Wertsch & Bivens, 1993).

This dialogic approach is based on the sociocultural theory of cognitive development. Vygotsky (1979) stressed the importance of social interaction in cognition and, consequently, in human development. The sociocultural theory has been further developed and established with decades of empirical studies (Scott & Palinscar, 2013) and confirms that learning and identity are socially constructed, mediated by language. Therefore, the meanings and interpretations that are created in interaction with others are later internalized by the individual: “In their own private sphere, human beings retain the functions of social interaction” (Vygotsky, 1962, pp. 164). In this vein, social environment is a key factor in the development or in the prevention of mental illnesses (Blanco & Vicente, 2003). Dialogism comes from different perspectives and disciplines. Particularly in psychology, the work of Vygotsky (1979), Bakhtin (1981), Wertsch (1993) or Mead (1982), among others, has been fundamental to understand higher mental functions and identity as dialogic processes derived from interpersonal activity (Fernyhough, 1996; Flecha, 2000; Larraín & Haye, 2014; Salgado & Clegg, 2011; Soler, 2004). This approach maintains that meanings are created in dialogues with other people because meanings are developed in processes of reflection between individuals (Bakhtin, 1981).

This process of appropriation and joint creation of meaning has shown to be particularly transformative when engaging individuals in a horizontal and egalitarian dialogue (García-Carrión et al., 2020). Indeed, Flecha (2000) pointed out that aspect by coining the concept of ‘egalitarian dialogue’ where dialogical exchanges occur among people who take on a dialogical stance based on equal validity of the arguments. Dialogical conversations are characterized by an egalitarian position of the speaker, regardless their status in the social context (i.e. patient-therapist), to facilitate the understanding and perceptions of reality. We argue dialogism-based practices are those interventions which follow the principle of egalitarian dialogue and where patients are agents of change and take part in decision-making processes.

Indeed, research has shown interventions based on dialogic principles that have reported positive outcomes in many different areas of cognition and development, reporting benefits in academic attainment (García-Carrión et al., 2020) and prosocial behaviour (Villardón-Gallego et al., 2018), among others. In addition, this type of dialogue can transform the discourse and the language of desire towards non-violent relationships (López de Aguileta et al., 2020). Moreover, this approach has been transferred to prisons, where the transformative potential for social reinsertion, creation of meaning and solidarity has been demonstrated (Flecha et al., 2013). Also, it is shown to promote social reintegration by encouraging the desire for change and the confidence in prisoners’ capacity for personal and social transformation (Álvarez-Cifuentes et al., 2018). Regarding mental health, research related to dialogic interventions has showed disruptive behaviours and affective symptoms decrease together with an improvement in personal well-being in children and adolescents (García-Carrion et al., 2019). Finally, this approach has demonstrated to enhance rehabilitation processes of people attending a socio-health care day centre with severe mental illness (Melero, 2017).

In clinical practice, using dialogic approaches boosts bidirectional and knowledge-generating relationships (Béhague, et al., 2020), especially in psychosis, since recovering should include a return to interpersonal connections and communal belonging (Lysaker & Buck, 2008). Identity is inherently dialogical or product of an ongoing dialogue both within oneself and between individual and others (Lysaker & Lysaker, 2001). In essence, the self is also considered social and relational, and it emerges on the basis of continuous engagements with the environment (Galbusera & Kyselo, 2019). Hence, psychosocial therapies, which involve the patient actively in a dialogue are crucial to promote recovery (Saiz & Chevez, 2009) and those dialogical encounters can be generative, specifically, in lives of people with psychosis (Seikkula, 2002). However, people with schizophrenia are usually left out of the dialogue, this diminishing their sense of agency and hindering their identity development (Holma & Aaltonen, 1995). Additionally, due to their neurocognitive difficulties, patients with schizophrenia struggle with maintaining an internal dialogue (Lysaker et al., 2003) and this disturbance also comprises their ability to respond to life context and challenges (Lysaker et al., 2006). It seems essential for patients with schizophrenia to verbalize their thoughts since, in doing so, they can better cope with the hallucinations they suffer. Through the externalization of hallucination stories, the person can provide knowledge of oneself and encourage introspection (Raballo & Laroi, 2011). Consequently, involving these patients in egalitarian dialogic interaction can help them to externalize thoughts and to promote awareness about their self.

Interventions based on a dialogic conception of self for treating psychosis, such as Narrative therapies, have shown improvements in the patients’ capacity to narrate self-experience and in quality of life (Lysaker & Buck, 2008). These therapies are based on the fact that narration is the principle of construction of meanings and, consequently, it forms identity (Ricoeur, 1991). Although this therapy shares the vision of relevance of language, it is different from dialogism in the way the author of the narrative is perceived. Narrative therapy attempts to reauthorize the traumatic history of the patient, whereas in the dialogic approach the narrative is jointly created between the participants. Another intervention aimed at tackling psychosis and based on dialogism is the Open Dialogue, which objective is to promote dialogue through which encourage change in the patient and her/his family (Seikkula et al., 2006). By discussing and externalizing her/his problems, the patient acquires more protagonism and control over her/his life (Holma & Aaltonen, 1997). This intervention system has already provided positive evidence around patient recovery: Patients seem to recover faster from psychosis, in addition to reducing days of hospitalization (Seikkula et al., 2003; Seikkula et al., 2006; Bergström et al, 2018) and chronicity (Aaltonen et al., 2011). This systematic review aims to contribute this field of knowledge by analysing the clinical and social effects of dialogic approach (psychological interventions based on dialogic principles) when treating people with psychotic diseases.

Method

A systematic review has been carried out following the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and its checklist designed for reviewing studies that evaluate the effects of health interventions including qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods designs (Page et al., 2021). We have also followed the recommendations offered by Rubio-Aparicio et al. (2018) on conducting meta-analyses and systematic reviews.

Search Strategy

This systematic review has been focused on analysing the potential positive effect of dialogic interventions on patients with psychosis. This question has been defined in terms of PICO (Aslam & Emmanuel, 2010), although no Comparator (C) criteria is established because the study is not focused on comparing interventions, but on identifying results of a specific approach: In patients with psychosis (Population) are dialogue-based or dialogical interventions (Intervention) effective in their recovery (Outcomes)?

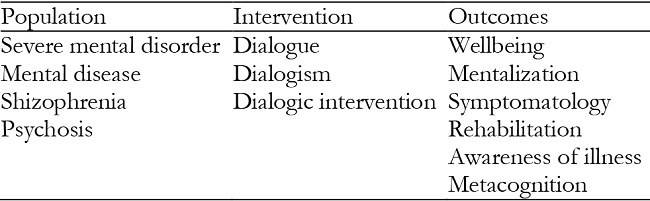

For the review, empirical articles published in international scientific journals in the areas of psychology, psychiatry, and mental health between 2010 and 2020 were searched and screened in three databases: Web of Science (WOS), Scopus and Psycinfo. This time frame was selected in order to collect only updated and novel information. The searches were conducted since September to December 2020. The keywords used in the search were established based on PICO and are shown in the following table (Table 1):

The keywords were combined in every possible way by the Boolean connector OR and AND were used to refine the search. All possible routes were created to exponentially combine all the options in each category, each Population keyword with each Intervention and Outcome keyword.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

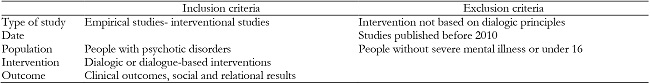

In order to identify and select the most relevant studies for the purpose of the review, the following inclusion and exclusion criteria were established (see Table 2).

Selection Process

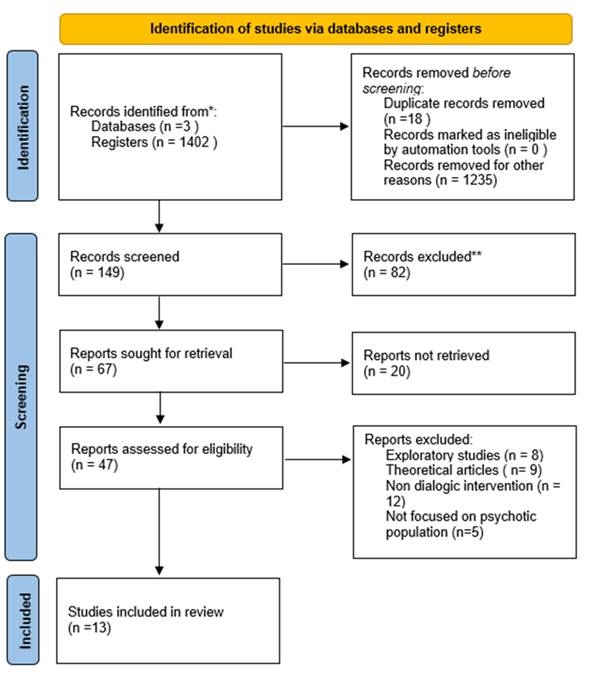

The first part of the search yielded a total of 1402 articles from indexed journals: 378 published in WOS, 311 in Scopus and 713 in PsycInfo. From initial search, 167 articles were selected based on their title in the 3 databases and, after discarding duplicates (n= 18), 149 articles remained in order to review the abstracts.

Abstracts of the 149 articles were reviewed, in this first review 67 articles were chosen for a more in-depth review (45 from WOS, 10 from Scopus and 12 from PsycInfo). From these articles gathered in the initial search, the titles and their authors were subsequently revised in order to eliminate articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. After eliminating articles focused on a non-dialogical intervention (n = 5), theoretical or conceptualization articles (n = 8), exploratory studies (n = 3) and conference proceedings (n = 5) 46 articles were presented. Those article were downloaded for an in-depth review (see Figure 1).

The three researchers examined the articles and extracted the most relevant information that was included in a spreadsheet. The information referred to: (a) study characteristics (author, country, selection criteria, design, data acquisition period), (b) population (target population, age and sample size), (c) settings, and (d) type of study. This review and discussion of the studies of the 47 articles led to the elimination of 34 articles that did not adequately meet the inclusion criteria (non-dialogical intervention = 12, theoretical paper = 9, exploratory study = 8, not focused on psychotic population = 5). Thus, a total of 13 articles were finally selected for analysis (Figure 1).

Quality Assessment/ Risk of bias assessment

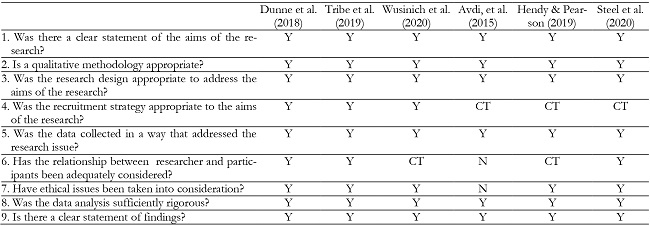

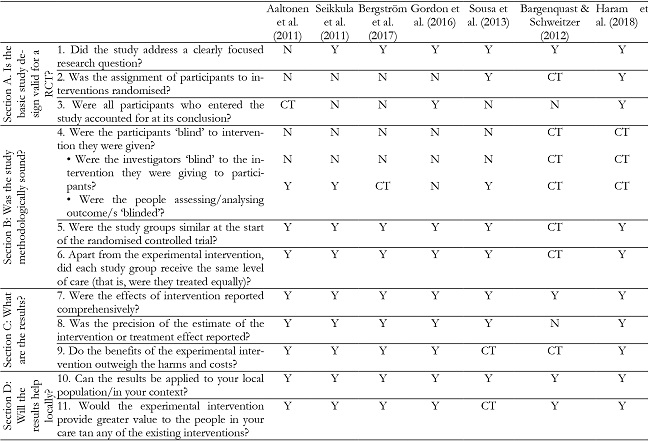

The quality of the selected studies was assessed using a checklist developed by Critical Appraisal Skills Programme to assess the quality and rigour of the studies included. In this case, CASP Randomised Controlled Trial Standard Checklist (2020) was used to assess the articles regarding clinical trials and CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist (2018) was employed to evaluate the qualitative studies selected. The purpose of this critical appraisal is to assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which a study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis. The results of the assessment are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3: Quality Assessment- CASP Randomised Controlled Trial Standard Checklist.

*Y: Yes, N: No, CT: Can’t tell

Data Analysis

For the analysis of the studies, the researchers developed an analytical grid to systematize the most relevant information for the purpose of the study: (a) author and year, (b) country, (c) title, (d) objective, (e) sample, (f) methodology, (g) type of intervention and (h) results. The researchers analysed the studies aiming at identifying how the interventions followed dialogic principles and the effects of the interventions on the target population. Data was categorized deductively, following the analytical grid, and is presented in Table 5.

Results

Results have been divided by dimensions according to the outcomes reported by the dialogic interventions conducted in the studies analysed. Eight studies found positive outcomes related to the clinic of the illness, such as medical changes, hospitalization, etc. In addition, four studies shown social improvements, along with reintegration into the labour market. Finally, eight studies also reported patients’ perceptions and opinions, showing acceptability and wellbeing feelings towards intervention.

Overall, the quality assessment applied to the qualitative studies revealed a clear statement of the aim of the research as well as an appropriate selection of design, methodology and data collection techniques for most of the studies. The data is also presented in a intelligible manner and ethical aspects are taken into account, except from Avdi et al. (2015). Finally, in some studies the recruitment of participant and relationship with the researcher is not properly tackled (Avdi et al., 2015; Hendy & Pearson, 2019; Steel et al., 2020). On the other hand, the assessment applied to the clinical trials reported a clearly focused research questions. However, in general, the design of the studies are not entirely valid for a trial, due to the lack of randomization of participants and sample death. Besides, for many of the articles assessed the investigators and participants were not blinded, except in some studies (Aaltonen et al., 2011, Seikkula et al., 2011 & Sousa et al., 2013). Nonetheless, the groups for the trial were similar at the baseline and had same level of care, results were presented in a clear way, so that they can be applied to other contexts.

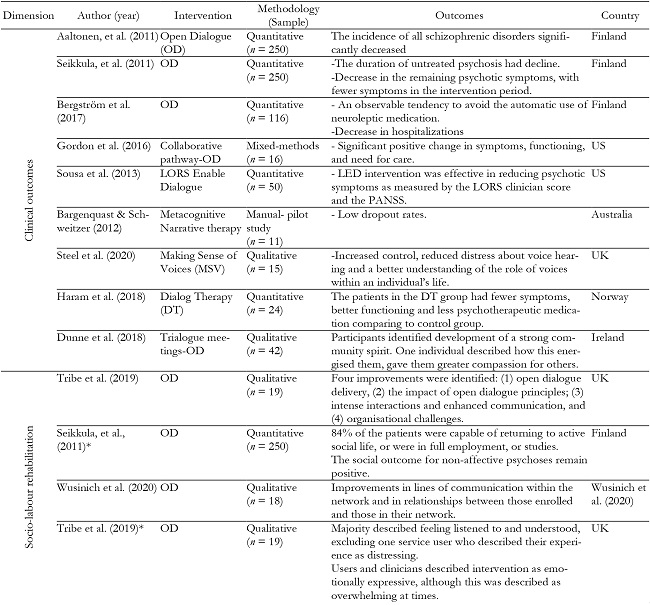

Below, a summary of the thirteen studies is presented in Table 5, that is divided by the clusters: a) Clinical outcomes, b) Socio-labour rehabilitation and c) Acceptability among patients. Moreover, the table presents studies’ authorship and year, type of intervention, country where the study was conducted and some of the main results reported.

Clinical outcomes

Among the positive clinical outcomes obtained in the dialogic interventions a reduction of psychotic symptomatology was reported in eight articles. Most notably, research focused on Open Dialogue (OD) has demonstrated obtaining promising symptomatologic results, by reducing or shortening symptomatic manifestations. OD aims to generate a dialogue between the patient, the family and the therapeutic team in order to putting the experiences that occur during psychotic episodes into words (Seikkula et al., 2006). A great importance is placed on the therapists’ dialogical stance, which is associated with a particular way of listening in a context of acceptance and understanding. In this approach, dialogue itself becomes the aim of therapy, because it is through dialogue that people reach more connection and meaning with the experiences and feelings of their lives (Avdi et al., 2015).

Research focused on Open Dialogue has showed a decrease in psychotic symptoms as well as psychiatric medication. The studies conducted by Aaltonen et al. (2011), Seikkula et al. (2011) and Bergström et al. (2017), implemented the Need Adapted Approach in Finnish Western Lapland, after 3 years of training for the staff, in three inclusion periods. In the follow-up, the 81% of patients did not have any residual psychotic symptoms and only 33% had used neuroleptic medication, showing that the incidence of schizophrenic disorders significantly decreased overtime. However, the annual mean of first admission patients increased, indicating that the decline in the number of the schizophrenic diagnosis was not due to a decline in the total use of psychiatric services (Aaltonen, et al., 2011). In the same way, Bergström et al. (2017) pointed that 95% of the patients spent less than one year as inpatient. Especially, 74% of the subjects at the initial contact and 45% of the subjects at any point during study period did not receive neuroleptics. To sum up, during the years that this intervention has been implemented, there have been fewer symptoms in the patients compared to the baseline of previous years. In the same way, by implementing OD, people request therapy at a younger age, so that the period for untreated psychosis is shorten. These changes made psychotic symptoms not to be as entrenched as before (Seikkula et al., 2011).

The Open Dialogue intervention has been transferred to other contexts with positive clinical outcomes. The study conducted by Gordon et al. (2016), which adapted the OD for an early-onset psychosis in the United States, reported a significant improvement in psychiatric symptomatology, global functioning and need for care. It also showed an almost significant decrease in spiritual beliefs (Gordon et al., 2016). These results are similar to outcomes shown by Sousa et al. (2013) which demonstrate that another dialogic intervention, named Levels of Recovery from Psychotic Disorders Scale (LORS) Enable Dialogue, was effective in reducing psychotic symptoms, measured by the Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale (Kay et al., 1987). Likewise, another study that analyses Dialogue Therapy, which consists of engaging in a collaborative dialogue with the patient, demonstrated achieving better functioning and fewer symptoms (Haram et al., 2018).

Another outcome found was the reduction of psychoactive medication and relapse rates (Sousa et al., 2013; Haram et al., 2018). This is also demonstrated by Bargenquast and Schweider (2015), who found there were lower dropout rates with an intervention called Metacognitive Narrative therapy, drawn upon dialogical narrative understanding of self and psychosis, articulated by Lysaker et al. (2011). Finally, increased control, reduced distress and a better understanding of the role of voices within an individual’s life was reported by the intervention Making Sense of Voices (Steel et al., 2020), based on Hearing Voices Movement (Romme & Escher, 1989) and which promotes a dialogical engagement with voices.

Socio-labour rehabilitation

Four articles reported improvements in socio-labour rehabilitation after implementing an intervention based on dialogic principles. With regard to socio- relational aspect, an intervention named Trialogue Meetings, based on dialogic principles aligned to the Open Dialogue approach demonstrated enhancing community spirit, as well as promoting participant to gain compassion for others (Dunne et al. 2018). These improvements, that emerged in the context of respect and trust developed in these dialogic interventions, are essential to strengthen relationships with other members.

The study conducted by Tribe et al. (2019) adapted the Open Dialogue approach to the context of the United Kingdom, and among the most significant improvements interaction patterns and communication skills appeared. Within the relational improvements, an increased use of symbolic language was identified by Avdi et al. (2015). They studied dialogic features in a qualitative study of OD therapy among a couple with psychotic illness. They reported that this therapy creates opportunities for the expression of strong feelings and difficult experiences. Finally, lines of communication are enhanced, and relationships improve within dialogic networks after adapting the Open Dialogue for people experiencing psychotic crisis in the United States (Wusinich et al., 2020). This is aligned to the results reported by Tribe et al. (2019).

Besides, the ability to work is an important indicator of the recovery of people with psychosis. Indeed, this ability was fostered in interventions based on dialogic approach, in which employment authorities are also involved (Seikkula et al., 2011). According to this study, Seikkula and colleagues (2011) confirmed that 84% of the patients involved in this network were capable to returning to active social life, or were in full employment, or studies after the treatment. These findings are in line with another study which presented that nine from fourteen participants were at work or in school in one year (Gordon et al., 2016). In some cases, for those who were not able to work (due to their psychotic crisis), they were capable of remaining in active social life despite possible symptomatology (Seikkula et al., 2011; Aaltonen et al., 2011).

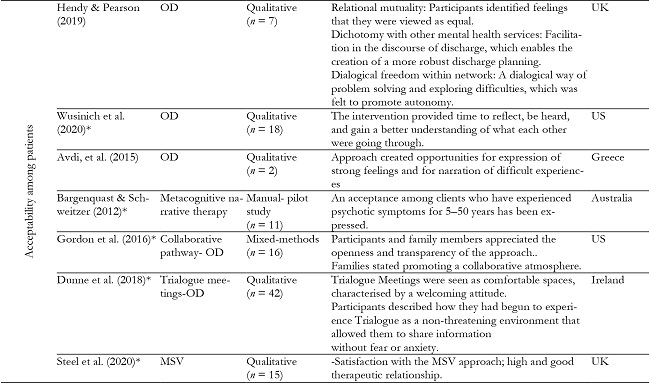

Acceptability among patients

Eight studies reveal patients’ perceptions and feelings about this kind of approach. Patients used to value positively this way of carrying out rehabilitation (Wusinich, 2020), as well as generating a great deal of acceptance among them (Bargenquast & Scheider, 2015; Steel et al., 2020) and good therapeutic relationship (Steel et al., 2020). Therefore, there is a general consensus in acceptability of this approach among patients.

Patients mentioned to appreciate openness, transparency and feeling part of decision making, they valued the promotion of collaborative atmosphere too (Gordon et al., 2016). Moreover, one of the themes that emerged as important in this therapeutic process was relational mutuality, seen as a feeling that they were viewed as equal within the network meetings. The differences between this approach and other mental health services was also mentioned in terms of OD being more helpful for patients, facilitating conversations about discharge planning. Finally, it was also highlighted the dialogical freedom evolved in this environment, that helped solving and exploring difficulties and promote autonomy (Hendy & Pearson, 2019).

Participants in these networks felt listened and valued. They particularly appreciated the process of creating a dialogic space where they were listened by the group and the therapist (Tribe et al., 2019; Hendy & Pearson, 2019; Wusinich, 2020). In this sense, reflective conversations, in which professionals shared thoughts and ideas openly, created a space for self-reflection in a supportive way (Hendy & Pearson, 2019). Dunne et al. (2018) also found this intervention to be perceived as comfortable spaces with welcoming attitude in which they were allowed to share information without fear or anxiety (Dunne et al. 2018).

It is reported that by means of sharing dominance, symbolic language and participation increased. The dialogic approach facilitated the joint construction of new words and meanings and created opportunities for expression of strong feelings as well as for narration of difficult experiences (Avdi, et al., 2015). This is similar to what Dunne et al. (2018) found, that is, participants highlighted that the intervention enabled them to come out of their “shells”. This context of acceptance and respect enhanced a better understanding of what they were going through (Wusinich, 2020), fostering increasing awareness of one’s mental health status.

Regarding to facilitators and the therapeutic team’s view, these spaces were seen as an overwhelmingly positive experience for participants (Dunne et al. 2017). Moreover, they felt this approach enabled the facilitators and the therapeutic team ‘s expression of their authentic self in their interactions with service users. However, OD has been perceived as a challenging way of working, although being selected as a preferred approach as well as therapeutic (Tribe et al., 2019).

Discussion

Following the tendency present in society of major presence of and request for dialogue (Soler-Gallart, 2017), there is a recent interest in examining therapies based on dialogue, narrative and discourse for treating psychosis (Avdi et al., 2015). Responding to this interest, our review has come to address the question of efficacy of such dialogical therapies. As observed in the results, interventions based on the dialogic approach have led to positive outcomes in clinical as well as socio-labour aspects. There has been shown improvement in psychiatric symptomatology and global functioning (Aaltonen et al. 2011; Sousa et al. 2013; Gordon et al. 2016; Haram et al., 2018), decreasing inpatient rates (Bergström et al. 2017). Related to socio-labour results, most of the patients were able to return to active social life, as well as to work (Seikkula et al. 2011; Gordon et al. 2016). Also, positive results in communication and communitarian outcomes were reported (Dunne et al., 2018; Tribe et al., 2019). Participants’ perceptions were mostly favourable, valuing positively this approach (Bargenquast & Scheider, 2015; Wusinich, 2020).

Within a similar conception, Narrative therapies have reported good clinical outcomes among severe mental illness (Vromans & Schweitzer, 2011; Newberg, 2016). Also, psychotherapies based on metacognitive approach, which are focused on patients self-experiences and making them sense of the challenges through dialogue (Lysaker et al., 2020), have demonstrated the development of a sense of personal agency, a greater capacity to tolerate and manage painful affects and emotion (Jong et al., 2017) and a increasing sense of psychosocial challenges (Hasson-Ohayon et al., 2017). Hence, it is widely accepted the importance of facilitating the re-emergence of internal dialogue through external dialogue. Psychotherapy should assist people with schizophrenia to develop a narrative that allows for recovery by creating a context for increasing self-awareness and agency (Lonergan, 2017).

Regarding the analysis carried out in this review, presents a deep and detailed understanding of the patients' perception and characteristics of the intervention. However, it emphasizes the need for controlled studies that analyse and report on the efficacy on specific variables. Besides, Open Dialogue is the most common intervention grounded on these dialogic principles in the mental health area with a relevant number of studies that report positive outcomes. Nevertheless, some critiques have pointed out the lack of high-quality evidence because research trials have not been carried out (Freeman et al., 2019). These limitations have been acknowledged and these do not diminish its relevance and significant potential (Freeman, et al., 2019) since its transferability to many cultures and countries showing good preliminary outcomes (Tribe et al., 2019) and its development has been carefully chronicled (Lakeman, 2014).

Conclusions

This systematic review has analysed and reviewed thirteen studies implementing interventions based on a dialogic approach among people with psychosis. From this analysis, clinical and socio-labour improvements have been identified, and a wide acceptability of a dialogic approach by the participants have been documented. The common feature of these interventions is that they are strongly grounded in the dialogic approach. They emphasize interaction, joint construction of meaning and account for the dialogical nature of the self, as well as the role of dialogical encounters in the therapy process. This aligns with the global trend on dialogism which is well-established in other psychosocial interventions, such as the social reintegration of inmates in prisons (Álvarez-Cifuentes et al., 2018) or people with disabilities (García-Carrión et al, 2020). Overall, the importance of taking this dialogic approach in all interactions with and among patients along all the rehabilitation process and beyond seems particularly relevant,.

Finally, the studies analysed in this systematic review do not include a protocolized intervention which this entails a difficulty to measure not only the outcomes, but also intervention criteria. In any case, a challenge that emerges is how to ensure that all members of a therapeutic team assume this dialogic stance and way of being. Although there are interventions based on these principles, it seems complicated to demonstrate a correlation between the outcomes and the approach, which makes difficult to isolate the specific characteristics. This lack of a protocolized criteria for implementing a dialogic intervention has entailed a limitation for this systematic review to define a particular inclusion criteria for establishing what is or not a dialogic intervention. Thus, it has not been possible to report measures of the degree of dialogism and its correlation with participants’ outcomes. Future research could contribute developing a more objective protocol to measure and quantify dialogic aspects of the environment in order to compare and establishing relationships with other variables.

In spite of these limitations, this review shows some clues that might sustain the hypothesis that dialogical approach-based interventions could have positive effect on psychotic diseases, yet according to the results there is no clear evidence on their effectiveness. Therefore, more rigorous studies are required in the field that provide an objective measure of the efficacy of dialogic therapies for psychotic patients.