Introduction

Adolescence is a time in which several physical, emotional and cognitive changes occur. Although stress occurs at every stage of life, adolescence, which is accompanied by biological and social changes, might be an especially stressful period (Arnett, 1999). It is a period through which escalation is being observed in stress-related psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression (Romeo, 2017). It was stated that anxiety disorders and chronic psychiatric disorders are the most common among adults, and the onset began during adolescence (Kessler et al., 2005; Sheean and Sheean, 2007).

Trait anxiety is defined as a relatively stable personality trait and a vulnerability to respond anxiously to stress and psychological threat (Spielberger et al., 1970). The anxiety experienced during adolescence has numerous predictors such as family relationships (Negriff et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020), being bullied in peer relationships (Stapinski et al., 2014; Zwierzynska et al., 2013), and physiological changes in the brain. Furthermore, with the increasing level of technology use, adolescents today face challenges such as comparing themselves with others, cyberbullying, social isolation, addiction problems, and these lead to an increase in their anxiety levels (Tomoniko, 2019). One of the possible determinants of anxiety can be personality traits, which are relatively stable and essential. In the current literature, it is possible to run across studies focus on the narcissistic personality traits of today’s generation. In this manner, grandiose narcissism is described by such attributes as arrogance, entitlement, exploitation, lack of empathy, and grandiosity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Nevertheless, studies investigating the relationship between anxiety and grandiose narcissistic personality traits yielded conflicting findings. Whereas some of the studies yielded a significant positive relationship between grandiose narcissistic personality traits and anxiety (Barry et al., 2015; Washburn et al., 2004), others found a negative relationship between these two variables (Barry and Kauten, 2014; Miller and Maples, 2011; Sedikides et al., 2004) and some of them found no significant relationship (Barry et al., 2019; Miller et al., 2011). In addition, it was emphasized that the role of grandiose narcissistic personality traits on internalizing problems of the youth such as anxiety and depression is ambiguous (Barry and Malkin, 2010). Accordingly, to find out more about the direction of the relationship between grandiose narcissistic personality traits and anxiety in our culture seems important. However, very few studies has investigated this relationship (Pirinççi, 2009, Atila-Ekinci, 2018). Furthermore, the conflicting findings may suggest that some mediator variables might play an important role in the relationship between grandiose narcissistic personality traits and anxiety. In this study, we consider that one of the possible mediator variable could be perfectionism.

Perfectionism is defined as “demanding of oneself or others a higher quality of performance than is required by the situation” (Hollander, 1965). Even few studies investigate the relationship between narcissism and perfectionism (Smith et al., 2016), and perfectionism and anxiety (Smith et al., 2018), none of them has investigated the mediator role of perfectionism in the relationship between grandiose narcissism and anxiety. It seems important to search the mediating role of perfectionism with the intent of intervening the perfectionistic traits in order to reduce the anxiety levels of narcissistic adolescents. Therefore, this study focuses on the relationship between grandiose narcissism and trait anxiety through the possible mediator role of perfectionism in adolescent. In this study, we also considered grandiose narcissism and self-esteem together in order to examine their effects on anxiety as it was suggested by Bushman and Baumeister (1998) that narcissism and self-esteem should be distinguished from each other. This requirement is detailed in the next paragraph. No other research has been found to date considering the control of self-esteem over grandiose narcissism.

Narcissism, Self-esteem and Mental Health

Self-esteem is defined as an individual's positive or negative attitude towards himself/herself (Rosenberg, 1965). Both people with high self-esteem and narcissism tend to feel pleased about themselves, and rate their abilities high, people with high self-esteem do not denigrate or underrate others unlike narcissistic people (Hyatt et al., 2018). Therefore, it seems likely that high self-esteem and narcissism may have different reflections on the mood of a person. There are findings reporting that individuals with high self-esteem are less likely to develop depression, regardless of whether they are narcissistic or not (Orth et al., 2016), and narcissism is beneficial for mental health only when it relates to high self-esteem (Sedikides et al., 2004). As a result, it is considered that it may be important to consider self-esteem while investigating the effect of grandiose narcissism on mental health. In the current study, the mediating role of perfectionism in the predictive effect of grandiose narcissism on general anxiety levels in a sample of adolescents is investigated. For this purpose, it was aimed to examine the effect of grandiose narcissism on these variables by controlling the effect of self-esteem.

Although it is believed that narcissistic people admire themselves greatly; indeed, they need validation, affirmation and reinforcement from their social environment (Pincus et al., 2009). Therefore, individuals with both grandiose and fragile narcissistic personality traits try to meet their need of affirmation and reinforcement by setting perfectionistic goals or perfectionistic self-presentation (Smith et al., 2016). In that point, perfectionism might have a key role in the meeting of these narcissistic needs. For this reason, we chose perfectionism as a mediator variable and considered as two main dimensions: adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism.

Narcissism, Self-Esteem, Perfectionism, and Anxiety

Perfectionism has been considered as a multidimensional construct until recent years (Frost et al., 1990; Hewitt and Flett 1991; Slaney et al., 2001). In recent years, perfectionism has been studied as a construct with two dimensions named perfectionistic strivings and concerns, which represented the adaptive and maladaptive dimensions. According to this latest view, perfectionistic strivings indicate the effort of achieving the goals determined by the individual, while perfectionistic concerns indicate the difference between the goals that the individual has set for their ideal self and real self (Stoeber and Damian, 2016). These higher-order perfectionism factors are measured by the Self-Oriented Perfectionism and Socially-Prescribed Perfectionism subscales of the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (Hewitt and Flett, 1991). Dimensions of perfectionism contribute to increased psychopathological symptoms, such as depression (Levine et al., 2019) and anxiety in adolescents to some extent (Essau et al. 2008; Pirinççi, 2009). Narcissistic adolescents might face higher anxiety due to both their personality traits and the way they seek the approval of others. Smith et al. (2016) conducted a meta-analysis study, and the results yielded a significant relationship between narcissism and perfectionism dimensions, and between perfectionism dimensions and anxiety in another meta-analytic study (Smith et al., 2018). Studies also indicate the significant negative relationship between self-esteem and maladaptive perfectionism, meaning that low self-esteem is a risk factor for maladaptive perfectionism (Besharat, 2009; Chai et al., 2019; Cokley et al., 2018; Elion et al., 2012; Hewitt and Flett, 1991; Luo et al., 2016; Stumpf and Parker, 2000; Taylor et al., 2016). In addition, the significant positive relationship between self-esteem and adaptive perfectionism was also indicated (Abd-El-Fattah & Fakhroo, 2012; Elion et al., 2012). Contrary, it was also found that there was no significant relationship between self-esteem and adaptive perfectionism (Chai et al., 2019; Moroz and Dunkley, 2015). Considering the relationship between narcissistic personality traits and self-esteem (Pantic et al., 2017; Seidikes et al., 2004), self-esteem was included as a control variable in the current research.

The Current Study

Current research addresses the relationships between grandiose narcissism, the adaptive and maladaptive dimensions of perfectionism, anxiety, and self-esteem within a holistic perspective. Since personality traits are relatively persistent, it is considered that determining the mediators that can be modified or managed via therapeutic interventions such as perfectionism, in the course of anxiety may help to reduce the negative effects of grandiose narcissistic personality traits on anxiety. Accordingly, the following hypothesized were tested in this research:

H1: a) Grandiose narcissism would be positively associated with anxiety, b) controlling self-esteem would strengthen (increase) in this relationship.

H2: a) Grandiose narcissism would be positively associated with the dimensions of perfectionism, b) controlling self-esteem would strengthen (increase) in these relationships.

H3: a) Dimensions of perfectionism would be positively associated with anxiety, b) controlling self-esteem would strengthen (increase) in this relationship.

H4: a) Dimensions of perfectionism would mediate in the relationship between grandiose narcissism and anxiety in adolescents, b) controlling self-esteem would strengthen (increase) the mediation.

In summary, this study was designed as a correlational study to investigate that adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism dimensions might have played mediator roles in the relationship between grandiose narcissistic personality traits and anxiety when self-esteem is controlled.

Method

Research Model

This study was designed as a correlational study. The study aimed to investigate the relationships among grandiose narcissism, self-esteem, perfectionism, and anxiety in adolescents. Self-esteem was included to model as a control variable.

Participants

The participants consisted of 338 [(Girls = 192 (56.8%), Boys = 146 (43.2%)] high school students from five public schools from five public schools in Eskişehir. The high schools in the city center were categorized according to their majors and we tried to reach the schools from different professions, such as technical, fine arts, social sciences etc. The age of the students ranged from 14 to 18-year-old with a mean of 15.84 (SD= 1.01). These participants were from a non-clinical sample.

Instruments

The participants completed the instruments including the Demographic Information Form, the Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (RSES), the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), the Child and Adolescents Perfectionism Scale (CAPS), and the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI).

Demographic Information Form: The form includes questions about gender, age, and grades of the participants was developed by the authors.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1965): The scale is commonly used to measure a person’s self-consideration about themselves. It is a four-point Likert type scale, (4) Very True, (3) True, (2) Wrong and (1) Very wrong with 10 items (e.g. “I take a positive attitude toward myself.”, “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.”). Adaptation of the scale into Turkish was conducted by Çuhadaroğlu (1986), and the test-retest correlation coefficient was reported as .75 in the adaptation study. Additionally, Çuhadaroğlu (1986) reported that Cronbach alpha was calculated.76 in Turkish transformation study. In the current study, interval coefficient was .87.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI;Spielberger et al., 1970): The inventory had two subscales and adapted to Turkish by Öner and Le Compte (1998). State anxiety dimension measures how respondents are feeling in that moment, while the trait anxiety dimension indicates how people generally feel anxious aside from current conditions. High scores mean higher anxiety levels. Adaptation studies showed that test-retest reliability ranged from .26 to .68. The trait anxiety subscale of the STAI was used in this study. This Likert type scale consisted of 20 items (e.g. “I worry too much over something that really doesn’t matter.”, “I am content; I am a steady person.”) which are scored from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). In the current study, interval coefficient was .83.

Child and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale (CAPS;Flett et al., 2001): The scale was developed to assess the dimensions of perfectionism in children and adolescents. It was adapted into Turkish by Uz-Baş and Siyez (2010). The CAPS has two subscales which are self-oriented perfectionism and socially prescribed perfectionism which represent the adaptive and maladaptive dimensions of perfectionism. Items (e.g. “I try to be perfect in everything I do.”, “Other people always expect me to be perfect.”) are scored on a five-point Likert type scale (5) Very True of me, (4) Mostly True, (3) Neither True Nor False, (2) Mostly False and (1) False Not at all true of me. Higher scores indicate greater perfectionism. Internal consistency of the scale was calculated as .72 for children, and .86 for adolescents, respectively. In the current study, interval coefficient was .85.

Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI-16;Ames et al., 2006): The scale was originally developed by Raskin and Hall (1979), and a short version of the measure (the NPI-16) was updated by Ames et al. (2006). Adaptation study of the scale into Turkish was applied by Temel (2008). The scale consists of 16 items (e.g. “I know that I am good because everybody keeps telling me so.”, “I am more capable than other people.”), and all items have a forced-choice response format. Higher scores refer to a greater grandiose narcissistic personality trait. An internal consistency coefficient was reported as .85 in the adaptation study. In the current study, interval coefficient was .71.

Procedure

The Ethical Committee of the Anadolu University confirmed the study. Then, written permission from the directorate of national education was obtained. The data were gathered during class times with the permissions of the principals of the schools. Written consent was obtained from all participants attended the study. The participants were provided detailed information about the purpose of the research, accessing conditions of the data, the right of privacy, and to withdraw from the study at any time of the process.

Statistical Analysis

We first computed arithmetic means, standard deviations, kurtosis and skewness values for all study variables. A hypothetical model was then tested via Structural Equation Modelling with latent and observed variables, and the analysis was run by Lisrel 8.80. Path coefficients in the model were assessed by model fit indexes. Regarding goodness of fit indexes, comparative fit index (CFI), Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI), the goodness of fit index (GFI) are expected to be higher than .90, but root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the Standardized Root Mean Squared (SRMR)is lower than .08 (Şimşek, 2007).

Results

Measurement Model

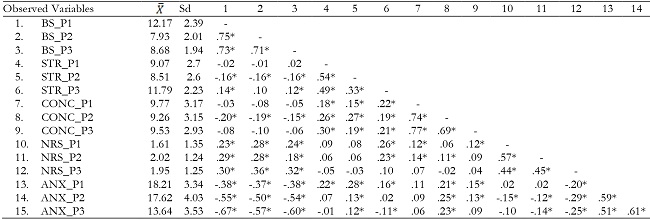

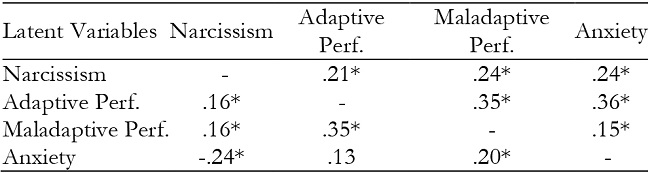

The proposed model consisted of four latent variables, in addition to the control variable. Three parcels were created for each latent variable; since the scales used in this study had one dimension. Means, standard deviations, and correlations among observed variables were reported in Table 1. All kurtosis and skewness values for observed variables were less than ±1; they were between -.010 and .738 for skewness, ranging from -.045 to -.655 for kurtosis. Therefore, the normality assumption was met. A test of measurement model without Self-Esteem resulted in acceptable goodness of fin statistics: χ2/df (249.22/80) = 3.12, p = .00, IFI =.95, NNFI =.94; CFI =.95; GFI =.91; SRMR: .075; RMSEA= .079 (95% CI for RMSEA = .068-.090). All factor loadings of observed variables on latent variables were high and statistically significant (standardised estimations ranged from .60 to .90). Correlations among latent variables were shown in Table 2. All correlation coefficients shown in Table 2 were significant, except for the relationship between adaptive perfectionism and anxiety.

Table 1: Means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlations among observed variables.

Note.*p <.05, BS_P1-3: three parcels from Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, NRS_P1-3: three parcels from Narcissistic Personality Inventory, STR_P1-3: three parcels from Self-oriented Perfectionism Subscale of Child and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale, CONC_P1-3: three parcels from Socially Prescribed Perfec-tionism Subscale of Child and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale, ANX_P1-3: three parcels from State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Table 2: Correlations of Latent Variables with (Above Diagonal) and without (Below Diagonal) Control Variable.

Note.*p <.05

Control variable was added to the measurement model and it was tested again. Goodness of fit statistics was: χ2/df (141.73/72) = 1.97, p = .00, IFI = .98, NNFI = .97; CFI = .98; GFI = .95; SRMR: .037; RMSEA= .054 (95% CI for RMSEA = .040- .067). Factor loadings of observed variables on latent variables ranged from .40 to .90 and all were statistically significant, except for third parcel of anxiety observed variables, but it was still significant. Factor loadings on self-esteem from all observed variables was between .01 and -.72 and three of them (one factor of adaptive perfectionism, and two factors of maladaptive perfectionism) were not significant (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Standardised parameters for measurement model with controlling self-esteem. *p <.05, BS_P1-3: three parcels from Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, NRS_P1-3: three parcels from Narcissistic Personality Inventory, STR_P1-3: three parcels from Self-oriented Perfectionism Subscale of Child and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale, CONC_P1-3: three parcels from Socially Prescribed Perfectionism Subscale of Child and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale, ANX_P1-3: three parcels from State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Values in the parentheses show standardized parameters without control variable.

Considering the effect of control variable on the measurement model, changing of goodness of fit statistics were statistically significant (χ2(8) = 107.49, p < .001). Correlations among latent variables controlled with self-esteem were presented in Table 2. As we can see, several correlations were changed dramatically namely the relationships between narcissism and anxiety were negative (r = -.24, p <.05) without control. However, it became positive (r = .21, p <.05) with it. Also, the correlation of adaptive perfectionism with anxiety was not significant (r =. 13, p >.05) but when control variable was added, it increased and turned into significant (r = .35, p <.05). Furthermore, correlations of narcissism with both adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism increased.

Structural Model

Structural model was tested and equated to acceptable goodness of fit statistics: χ2/df (197.20/49) = 4.02, p = .00, IFI = .92, CFI = .92; GFI = .91; RMSEA = .095 (95% CI for RMSEA = .081-.11). The model was tested once again, this time self-esteem was added to the model as control variable and it resulted in, as expected, acceptable goodness of fit statistics: χ2/df (230.00/74) = 3.10, p = .00, IFI = .96, CFI = .95; GFI = .92; RMSEA = .079 (95% CI for RMSEA =.068-.091). Standardized estimations of latent variables, which were shown from both structural model tests, were seen in Figure 2. As we can see from the outcome, changing of relationship estimations in the measurement model continued in the structural model as well. Furthermore, standardized path coefficient from maladaptive perfectionism to anxiety were statistically significant (β = .22, p < .05) without self-esteem it becomes nonsignificant (β = .01, p > .05) with a control variable. This path was discarded from the model, and model gave again, acceptable goodness of fit statistics: χ2/df (230.09/75) = 3.10, p = .00, IFI = .96, CFI = .95; GFI = .92; RMSEA = .078 (95% CI for RMSEA =.068-.091). As it can be seen clearly, discarding this path from the model caused appreciable change in the goodness of fit statistics [x2 (1) = .09, p > .05]. Results of structural model with control variable showed that indirect effect of narcissism on anxiety through adaptive perfectionism was significant (t = 2.69, p < .05).

Figure 2. Standardised parameters for measurement model with controlling self-esteem. *p <.05, BS_P1-3: three parcels from Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, NRS_P1-3: three parcels from Narcissistic Personality Inventory, STR_P1-3: three parcels from Self-oriented Perfectionism Subscale of Child and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale, CONC_P1-3: three parcels from Socially Prescribed Perfectionism Subscale of Child and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale, ANX_P1-3: three parcels from State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Values in the parentheses show standardized parameters without control variable.

Regarding explained variances, adaptive perfectionism, maladaptive perfectionism and narcissism explained 15% of anxiety when self-esteem was controlled and 12% without controlling.

Discussion

This study was carried out to examine the mediator roles of perfectionism dimensions in the relationship between grandiose narcissism and anxiety when self-esteem was controlled. The findings indicated that adaptive perfectionism mediated the relationship between grandiose narcissism and trait anxiety. In the literature, positive relationships were found between grandiose narcissism and adaptive perfectionism (Smith et al., 2016), and between adaptive perfectionism and anxiety (Xie et al., 2019) in meta-analysis studies. These findings supported the results of the current research. Hewitt and Flett (1991) conceptualize adaptive perfectionism, as setting exacting standards and stringently evaluating own behaviors to avoid failures. They also pointed out that adaptive perfectionism causes harsh self-criticism when these personal high standards and expectations about being perfect have not been met. The findings of the current study supports that narcissistic adolescents tend to strive for perfection, and this tendency leads to an increase in their anxiety levels when their self-esteem level was controlled.

It was also found that there was a negative relationship between grandiose narcissism and trait anxiety. On the other hand, a negative relationship between nonpathological narcissism and anxiety was reported in the previous studies (Barry and Kauten, 2014; Miller and Maples, 2011; Sedikides et al., 2004). The inconsistent findings between these variables were indicated in the literature (Barry and Malkin, 2010). In the current study, when self-esteem was controlled, this relationship was getting positive. This changing proves that, self-esteem seems to have a protective role when studying with grandiose narcissism and trait anxiety.

The findings indicated that there was also a significant positive relationship between grandiose narcissism and maladaptive perfectionism. This finding is supported by recent studies, which were carried out on adolescents (Curran et al., 2017; Farrell and Vaillancourt, 2019). The finding would have been explained by the nature of the adolescence period. As known well, one of the basic psychological needs during adolescence period is being socially accepted by peers (Steinberg, 2007). Therefore, it can be assumed that adolescents with grandiose narcissism traits tend to seek social approval by trying to be perfect or presenting a perfectionist appearance because of the developmental period, they are in. Pincus et al. (2009) also supported this need for external validation and admiration of narcissists. In the current study, this positive relationship enhanced when self-esteem was controlled. Once more, self-esteem seems to protect adolescents against the negative consequences of grandiose narcissism.

Furthermore, the positive relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and trait anxiety is consistent with the previous meta-analysis studies that have examined the psychopathological consequences of maladaptive perfectionism, particularly in non-clinical populations (Limburg et al., 2017; Xie et al., 2019). In addition, youths’ anxiety level has been predicted by maladaptive perfectionism (Damian et al., 2017), and the highest anxiety level was found among maladaptive perfectionists (Gnilka et al., 2012; Richardson et al., 2014). Unexpectedly, when self-esteem was controlled, the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and trait anxiety decreased. Furthermore, this relationship was getting non-significant in the structural model. In other words, maladaptive perfectionism had not a mediator role between grandiose narcissism and trait anxiety when self-esteem was controlled. It seems that, adaptive perfectionism has a stronger role in the current structural model.

Implications, Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Several practical implications can be derived from the results of the study. First, the results indicated that adaptive dimensions of perfectionism had a mediator role in the relationship between grandiose narcissism and anxiety. Therefore, prevention and intervention programs can be developed to decrease perfectionistic beliefs and attitudes of adolescents displaying negative self-evaluations. Secondly, therapeutic interventions need to focus on adolescents’ unrealistic personal standards.

In addition to practical, theoretical implications can be pointed out. First, the research findings proved that self-esteem had a critical role when studying narcissism and mental health relationships. Therefore, self-esteem levels of the adolescents might be added as a control variable to the studies, or its moderator role could be tested in similar models in future research. Secondly, the relationship between narcissism and anxiety might be considered in those who have low and high-level narcissism. Similarly, the same analyses can be applied to the low and high self-esteem groups.

The present study has some limitations. The first limitation is about using self-reporting measures due to their vulnerability of manipulation. This limitation may be overcome in future studies by collecting data from people who have close relationships with the participants like friends or family members. The second limitation is about the participants. This study was carried out with the adolescents in high school years. Thus, one needs to be cautious about generalizing these findings to adolescents (both early and late) or other age groups. This study is a cross-sectional study. In order to understand the relationships among these variables better, longitudinal studies may be designed. Vulnerable and grandiose dimensions of narcissism should be involved together in research to understand the unique relationship between narcissism and perfectionism dimensions as suggested by Stoeber et al. (2015), and future research should consider this suggestion. Finally, the participants represent mainstream Turkish culture. Comparative studies may give an opportunity to pinpoint the effect of different cultures on these relationships.

Conclusion

The results of the present study showed that the adaptive dimension of perfectionism mediated the relationship between grandiose narcissism and trait anxiety. Based on the findings of this study, practitioners need to intervene on the self-oriented perfectionistic tendencies of adolescents while decreasing their anxiety levels. Furthermore, future studies may take the vulnerable dimension of narcissism into consideration and repeat the mediation model with the same variables.