Introduction

Adolescence is an important period of growth and maturation in which young people increasingly find more social relationships outside the family and demand greater autonomy (World Health Organization, 1986). At the same time, parents continue to educate and monitor their children's behaviour, but these may feel controlled and fail to understand that parents are concerned about them. Handling these new family dynamics is not easy for any of the family members, and on certain occasions, the family does not have or fails to find the necessary resources to cope with changes in an acceptable way. Thus, family relationships potentially become more conflictive. It is also possible that behavioural problems which may have originated in childhood become dangerous at this stage. The onset of such behaviours can be early, with violent behaviours appearing in the transition from childhood to adolescence, or late, if they appear towards the end of the adolescent stage (Holt, 2016). Simultaneously, parents possibly do not have the necessary competence to control their children's behaviour. However, a distinction should be made between extremely violent behaviours of children to parents (repeated physical violence) and those that may be considered “usual” in adolescence (e.g., sporadic verbal aggression).

Youth-to-parent aggression (YPA) is defined as young people consciously directing aggression toward one parent or caregiver, repeatedly over time, when the perpetrator and the victim habitually live together (Ibabe, 2020). This definition excludes assaults occurring in a state of diminished consciousness which disappear when consciousness is regained, those caused by severe mental deficiency, and parricide with no history of previous assaults. YPA has long been kept hidden within families, but in the last decade it has become more relevant because health professionals have increasingly observed this type of violence (Coogan & Lauster, 2015) and because the number of complaints is increasing internationally (e.g., in Australia, Moulds et al., 2018, and the United Kingdom, Condry & Miles, 2012). The number of complaints of YPA in Spain has been stable over the last decade (between 4,000 to 5,000 complaints against minors), and it is possible that this type of crime has become consolidated as a problem endemic to society (General Prosecutor's Office of Spain, 2019). However, according to some experts, only the most serious cases are reported, representing between 10% and 15% of the total (Fundación Amigó, 2019). In addition, the official data do not include YPA crimes of older children, despite the existence of this problem also being verified in different studies (Ibabe, 2020; Simmons et al., 2018). The international prevalence of physical youth-to-parent aggression at some point in the previous year is between 5% and 21% (Simmons et al., 2018).

Psychological characteristics of YPA perpetrator and their families

When it comes to severe YPA (clinical population: with psychological disorders, or legal population: with criminal acts), male children are the most frequent perpetrators (Moulds et al., 2018). In contrast, when analysing mild physical YPA, differences between boys and girls are not found or are very small, although psychological YPA is slightly more frequent among daughters (Gallagher, 2008; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2011).

The psychological profile of adolescents who perpetrate YPA includes low empathy and high impulsivity, low autonomy, self-esteem, and tolerance of frustration, as well as arrogance, conceitedness, and beliefs that justify violence (Calvete et al., 2011). They also present maladjustment at school and substance use (Contreras et al., 2012; Ibabe et al., 2014b; Johnson et al., 2018) and externalizing symptoms or antisocial behaviours outside the family context (Jaureguizar et al., 2013). They use violence in other contexts (Boxal & Sabol, 2021), and in particular, some research shows that YPA facilitates dating violence (Ibabe et al., 2020), or that both types of violence co-occur (Fernández-González et al., 2021). Finally, these adolescents may often have depressive symptoms (Ibabe et al., 2014a) and comorbid mental health problems (Moulds & Day, 2017).

At the family level, when YPA is severe, the mother is the victim in most cases (Boxall & Sabol, 2021; Moulds et al., 2018), but with mild violence the aggression is directed equally at mothers and fathers (Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2011). This type of violence has been linked to changes in family structure resulting from the separation of parents (Pagani et al., 2003), with single-parent households being particularly vulnerable (Armstrong et al., 2018). Other aspects explaining YPA are low family cohesion, poor communication, affection, parental control (Aroca et al., 2014), and poor parental discipline (Calvete et al., 2011; Contreras et al., 2012). These are families characterized by conflicting relationships between their members (Contreras & Cano, 2014), and even marital violence and/or mistreatment by parents of children (Armstrong et al., 2018; Calvete et al., 2011). A recent meta-analysis corroborates that the indirect and direct exposure of adolescents to family violence predicts YPA (Gallego et al., 2019).

YPA intervention programs

Although there are intervention programs for YPA situations based on different treatment perspectives (psychodynamic, systemic, cognitive-behavioural or psychoeducational), specific interventions are scarce (Nowakowski & Mattern, 2014) and lack a sufficient amount of empirical support (O´Hara et al., 2017). Recently, Ibabe, Arnoso and Elgorriaga (2018) carried out a review of evidence-based intervention programs at the international level involving ten databases and concluded that there is no evidence-based intervention program specific to YPA (registered in international databases). Two generic programs to improve family climate or children's behaviour problems stand out which could be useful for YPA (Multisystemic Therapy and Life Skills Training), although at the moment, their effectiveness has not been verified for this specific type of violence. For this reason, searches were made in Google Scholar, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES and Psicodoc for specific YPA programs using the following selection criteria: professional experience of the authors, good level of protocolization of the program and accessibility of the materials, and existence of intervention evaluation results. One of the most notable programs for dealing with situations of YPA at the American level is Step up (Routt & Anderson, 2004), which has been adapted and applied in different countries. At the European level, we find Break4Change (Break4Change, 2015) and Nonviolent Resistance (Coogan & Lauster, 2015), and in the Spanish context, Educational and Therapeutic Treatment for Child-to-Parent Aggression can be highlighted (González-Álvarez et al., 2013). Although some present a degree of empirical evidence of their effectiveness, they cannot be considered evidence-based programs.

The Early Intervention Program in Situations of Youth-to-Parent Aggression (EI-YPA, Ibabe et al., 2019) was the only one found for incipient YPA cases with a good level of protocolization for its three subprograms (involving adolescents, parents and families, respectively). It is available online for any clinical psychology professional to implement and offers some favourable empirical evidence (Ibabe et al., 2018).

Previous results of the EI-YPA program

Previous studies have published the short-term treatment effect of the EI-YPA program in Spanish families on the outcome variables of children and parents (Arnoso et al., 2021; Asla et al., 2020; Ibabe et al., 2021). These studies report that children and parents have fewer behavioural and emotional problems after treatment when the program lasts about 6 months. Specifically, the EI-YPA program is an effective intervention for reducing physical and psychological YPA between pre-intervention and post-intervention, as well as for depressive symptomatology outcomes of children in the Children and Family Services context (Ibabe et al., 2018; Ibabe et al., 2021). Moreover, all family members perceived a higher level of empathy just after completing the early intervention program with medium effect (Ibabe et al., 2018). However, previous studies regarding EI-YPA evaluation with adolescent population have two important limitations. First, the effects of this intervention program in the medium and long term have not been studied (in a follow-up phase), and second, the small sample size of these studies limits their statistical power, thereby reducing their chances of detecting a true effect.

In a study with parents to analyse medium-term effects (follow-up phase, 6 months after treatment), fewer inappropriate discipline and clinical symptoms were observed (Arnoso et al., 2021). Specifically, the use of corporal punishment and depressive symptomatology were much lower in follow-up evaluation than pre-intervention evaluation, with large effect size. There is also evidence that the level of satisfaction of the participants and the therapists with the program was favourable (Asla et al., 2020). Results of all previous studies reflect the EI-YPA program's short-term efficacy based on the decrease of externalizing and internalizing behaviour of children and parents. Although results of parents as participants have already been analyzed in the medium term, we do not know what happens one year after starting the intervention program in the adolescent population or to what extent YPA, clinical symptoms of adolescents, and their perception of child-parent relationships improve.

Study objectives

The main aim of this study was to assess the medium-term effects of the Early Intervention Program in Situations of Youth-to-Parent Aggression (Ibabe et al., 2019) on adolescents. To this end, specific objectives were set:

To analyze the adolescents' levels of satisfaction, learning and interest with regard to the contents of the adolescent group sessions and how well these were connected to their lives.

To check whether both physical and psychological YPA directed at fathers and mothers decreased after completion of the program, and whether the effects were maintained at six months.

To analyze whether, at six-month follow-up, adolescents showed a lower level of clinical symptoms (irrational beliefs, depressive symptoms, emotional instability, and low empathy), perception of family conflict and a higher level of life satisfaction.

Method

Participants and design

At the start of the program, 39 families living in Spain with children aged between 12 and 17 agreed to participate (N = 98) from 5 intervention groups. These families were made up of 37 adolescents (27 sons and 10 daughters), and 61 parents (39 mothers and 22 fathers). Exceptionally, some mothers attended the parent subprogram without their children participating in the program. Two of the adolescents came from the same family. The dropout rate was calculated by taking into account participants who stopped attending (voluntarily or were referred to another service on the grounds of severity) or who did not meet 70% minimum attendance. Of the 37 adolescents who started the program, 6 (4 boys and 2 girls) did not complete both the adolescent and family subprograms (16%). Three adolescents (two boys and one girl) were referred to the Provincial Council of Álava because in the course of the program, YPA increased to a higher level of severity. Thus, the overall success rate of adolescents in the program was 84% (n = 31; 23 boys and 8 girls).

In this study an ABA single-case experimental design was applied, which includes two attempts to demonstrate an intervention effect. In this type of design, repeated measures are taken on a single participant or group under no-treatment (A-baseline) and treatment conditions (B), and the subject or group serves as its own control (Macgowan & Wong, 2014).

EI-YPA program features and contextualization

The target population of this program is members of families with children aged between 12 and 17 presenting two inclusion criteria: a) YPA behaviours as their main problem, b) and simultaneously meeting the criteria of mild or moderate parental incapacity to control the behaviour of their child or adolescent, according to the BALORA instrument (Arruabarrena, 2011). In addition, exclusion criteria are: a) not being able to understand or speak Spanish fluently, b) repeated child-to-parent physical aggression, and c) severe cases of child abuse.

This program has a psychoeducational orientation, with cognitive-behavioural activities, and takes a systemic perspective on family intervention, seeing adolescent violence as a symptom of family conflict. The program takes place in a group format (5-10 participants) lasting approximately 6 months (24 weeks) and is limited to 8 families. It has three subprograms with a different number of sessions (adolescents 16, parents 11 and families 8). The content of the Adolescent Subprogram is focused on thoughts that undermine self-concept and self-esteem, as well as those beliefs that maintain and justify family violence.

This program was promoted by the Child and Family Service of Vitoria-Gasteiz city council (Spain), and developed by Ibabe et al. (2019). Relevant aspects of two specific YPA programs (Step Up, Routt & Anderson, 2004; Educational and Therapeutic Treatment for Child-to-Parent Abuse, González-Alvarez et al., 2013) have been integrated into the program. Adaptation of the program to the context of the Vitoria-Gasteiz city council was a participatory process led and coordinated by Loli García and Belén Ceberio. The implementation of the program was carried out by IPACE, Applied Psychology, an entity contracted by Vitoria-Gasteiz city council. The implementation of the program was carried out by three psychologists (one man and two women) and one supervisor. These professionals had a manual detailing the protocol necessary to carry out the intervention. Additionally, before starting the first intervention, the therapeutic staff received training from the research team on the intervention program and the evaluation design. During the development of the program with the first intervention group, the therapeutic team met monthly with the research team, and subsequently every three months. For the rest of the time there was continuous communication to comment on incidents or doubts.

Variables and Instruments

For each instrument below, the type of informant is specified (child-C and parent-P). Socio-demographic data (C-P). Adolescents were asked to complete a questionnaire with socio-demographic data such as age, sex, place of birth, place of residence, country of origin, time living in the Basque Country (for people born outside the Basque Country), family structure, marital status of parents, number of siblings, school situation, or potential trouble with the police. In addition to these characteristics, parents were asked about their educational level, employment status, and level of family income.

Youth-to-parent aggression (P) (Adolescent Child-to-Parent Aggression Questionnaire, Calvete et al., 2017). The ten items used with adolescents to assess physical and psychological YPA were adapted, with the parents now being the informants (e.g., You have been insulted or sworn at by your son/daughter). It was considered that parents are better informants than adolescents because the latter could state a lower level of violence for reasons of social desirability. In the case of parents, internal consistency measured with Cronbach's alpha was acceptable: physical aggression (pre-intervention = .78, post-intervention = .74 and follow-up = .89), psychological aggression (pre-intervention = .84, post-intervention = .86 and follow-up = .81) and global aggression (pre-intervention = .78, post-intervention = .88 and follow-up = .75). With mothers, the Cronbach´s alpha coefficient was acceptable: physical aggression (pre-intervention = .73, post-intervention = .71 and follow-up = .76), psychological aggression (pre-intervention = .70, post-intervention = .84 and follow-up = .86) and total aggression (pre-intervention = .72, post-intervention = .83 and follow-up = .87).

Depressive symptoms (C) (Children's Depression Scale (CDS), Lang & Tisher, 2014). This scale comprises three subscales of eight items each with five Likert-type response options (from 1 = Never to 5 = Very often): Affective response (e.g., sometimes I think this life is not worth living), Social problems (e.g., I often think nobody cares about me), and Self-esteem (e.g., I often think I am not worth much). The alpha coefficient for the scale was excellent (pre-intervention = .93, post-intervention = .96 and follow-up = .97), while for the subscales it was acceptable-good: affective response (pre-intervention = .78, post-intervention = .87 and follow-up = .86), social problems (pre-intervention = .82, post-intervention = .90 and follow-up = .95) and self-esteem (pre-intervention = .85, post-intervention = .90 and follow-up = .93).

Irrational beliefs (C) (Irrational Beliefs Inventory for Adolescents, Cardeñoso, & Calvete, 2004). This inventory is made up of a total of 37 Likert-type items with five response options (from 1 = Totally disagree to 5 = Totally agree) (e.g., I think I'm stupid when I miss something important). These are divided into six subscales: Need for approval/success (8 items), Helplessness (8 items), Blame proneness (5 items), Avoiding problems (4 items), Intolerance to frustration (3 items) and Justification of violence (9 items). The Cronbach alpha coefficient was excellent for the scale (pre-intervention = .88, post-intervention = .91 and follow-up = .86), while the coefficient for the subscales varies from .33 (Intolerance to Frustration) to .86 (Justification of violence). Subscales with internal consistency lower than desirable (α < .70) were not used in data analysis.

Emotional instability (C) (Emotional Instability, IE, Caprara & Pastorelli, 1993; Spanish adaptation by Del Barrio et al., 2001). This questionnaire describes a lack of self-control in social situations as a result of poor ability to control impulsivity and emotionality. It includes 20 items with three response options (often, sometimes or never). Cronbach's alpha was satisfactory in three conditions (pre-intervention = .77, post-intervention = .86 and follow-up = .78).

Satisfaction with life (C) (Satisfaction with life scale, SWLS, Diener et al., 1985; Spanish adaptation by Atienza et al., 2000). This consists of five Likert-type items with five response options (from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree) measuring the extent to which life expectations are met (e.g., So far I have gotten the important things I want in life). Cronbach's alphas were good (pre-intervention = .79, post-intervention = .92 and follow-up = .85).

Empathy (C) (Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), Davies, 1980; Spanish adaptation by Pérez-Albeniz et al., 2003). Two subscales were selected: Perspective taking (e.g., When I see someone being taken advantage of, I feel kind of protective towards them) and Empathic concern (e.g., Sometimes I try to understand my friends better by imagining how things look from their perspective). Each subscale consists of eight Likert-type items with five response options (from 1 = It describes me very well, to 5 = It does not describe me at all). Cronbach's alpha coefficient was quite acceptable in the subscales (Perspective taking was acceptable, pre-intervention = .77, post-intervention = .70 and follow-up = .83; Empathic concern pre-intervention = .74, post-intervention = .72 and follow-up = .67) and satisfactory for the global scale (pre-intervention = .80, post-intervention = .79 and follow-up = .84).

Family conflict (C) (Family Environment Scale (FES), Moos & Moos, 1981, in its Spanish adaptation, TEA Ediciones, 1984). The family conflict subscale comprising nine items with two response options (true-false) was selected (e.g., people in our family frequently criticize each other). In this study, the alpha coefficient was acceptable in three evaluations (pre-intervention α = .71; post-intervention α = .70; follow-up α = .70).

Satisfaction and acceptability of the Adolescent Subprogram (C) (inter-session evaluation). The process was evaluated by means of inter-treatment assessments by participants at the end of each session. The acceptability of and satisfaction with different aspects (motivation, satisfaction, learning, and related to their life) were assessed in each session (e.g., To what extent were you motivated in today's session?) on a Likert scale from 0 (Not at all) to 10 (Very motivated).

Procedure

The program was implemented with five intervention groups between March 2017 and October 2020. Adolescents participated in Adolescent Subprogram and Family Subprogram. The Adolescent Subprogram was conducted by the same therapist (a male psychologist) except one intervention group, while the Family Subprogram was conducted by the same therapist (a woman psychologist). All intervention groups or Adolescent subprogram were similar in gender proportion, age, and cultural background, while in Family Subprogram participated the members of single family. Vitoria-Gasteiz city council social services staff identified families which suffered YPA situations and invited them to participate in the program. Parallel to this, an awareness-raising campaign was carried out to reach other families who were not users of social services.

The evaluation protocol was applied by some fourth-year psychology students (the first three intervention groups) and by a psychologist of IPACE (the last two groups) not connected with the intervention. These persons were trained by the research team to conduct the evaluation and they were not aware of the hypotheses and study variables. However, they knew that the study design did not have a control group. The protocols were applied at the IPACE premises in a space familiar to the participants at three separate times: pre-intervention (7-10 days before intervention), post-intervention (7-10 days after intervention) and follow-up (six months after intervention). The evaluations were carried out at the IPACE Applied Psychology facilities. In the pre-intervention evaluation, each family was called, while in the post-intervention and follow-up evaluation they were called according to the work group (adolescents and fathers/mothers). In pre-intervention evaluation family members were asked to complete the evaluation protocol. In any case, the evaluation was carried out in a large room in which a physical distance between the participants was ensured to guarantee their privacy. Inter-session evaluation of satisfaction and level of acceptability was carried out for each session of the Adolescent Subprogram. This study complied with all the ethical requirements in accordance with the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Beings of the Basque Country University (M10-2019-142) as well as relevant international (American Psychological Association) ethics guidelines. All participants gave signed informed consent and their data was used anonymously.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics 23 statistical package. To obtain profiles of the adolescents and their families, descriptive analyses (percentages and means) of all participants starting the program were carried out. Subsequently, with the aim of analysing the level of satisfaction and acceptability of the Adolescent Subprogram, the average for each session was calculated together with the global mean, and a graph was prepared to reflect changes in these indicators.

Subsequently, to study the effects of the intervention, those adolescents and parents who finished the program and completed the assessment on at least two different occasions were selected. Descriptive analyses of YPA by intervention group are showed, since it does not make sense to do so at an inferential level due to the small size (5-7 adolescents) of the groups. Comparisons of means of repeated measures were made for all participants together (pre-post; post-follow-up; pre-follow-up). As some adolescents did not complete the program and others did not perform all the assessments, the data analyses were performed with 71 participants, 22 adolescents (17 boys and 5 girls) and 49 parents (18 fathers and 31 mothers) from 29 families.

Student's t analyses were performed for related samples, after analyzing the possibility of using parametric tests for the normality of each dependent variable, and the assumption of homoscedasticity was verified by Levene's test at each comparison of means. This statistic shows the effect of the intervention based on the following criteria: low effect d = .20, medium effect d = .50 and high effect d = .80 (Cohen, 1977). It should also be noted that the information corresponding to YPA was based on parent report. For the remaining variables analyzed, the adolescents themselves were the source of information.

Results

Profile of adolescents and families participating in the program

The mean age of 37 minors (27 boys and 10 girls) was 14.41 years (SD = 1.59) and most were between 13 and 16 years old. Adolescents born in the Basque Country (Spain) made up 83% of the sample, 5% came from other autonomous communities and 12% from other countries. Forty-two percent of adolescents lived with their biological parents, 36% with the mother, 11% in a reconstituted family, 6% adoptive family, 3% with the father and 2% with grandparents without biological parents. Twenty six percent stated they were doing well or very well at school, 40% normally, 34% badly or very badly. Furthermore, 50% had skipped school occasionally without justification, while 27% of them did so regularly. Lastly, 22% of adolescents pointed they had been in trouble with the police as a consequence of their behaviour towards their parents, and 31% of them for other reasons.

Most parents were born in Spain (88%), and 22% of all parents had university studies, 56% an upper secondary level of education or vocational training, and 22% primary education. Regarding the level of family income, 17% earned between €650-€1,000 monthly, 17% between €1,001-€1,500, 10% between €1,501-€2,000, 13% between €2,001-€2,500, 11% between €2,501-€3,000, and 28% more than €3,000. Four percent declared that they had minimal or no income.

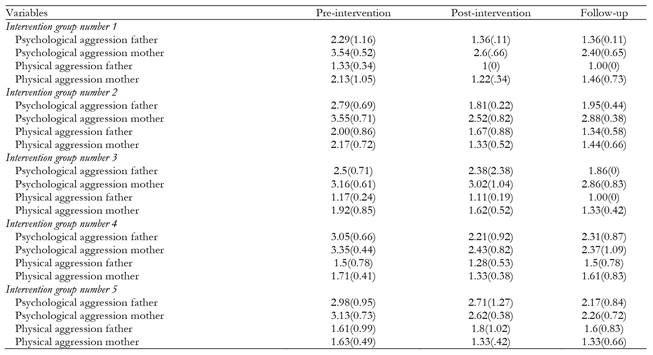

Means and standard deviations of physical and psychological YPA by intervention group in each evaluation time (pre, post and follow-up) are presented in Table 1.

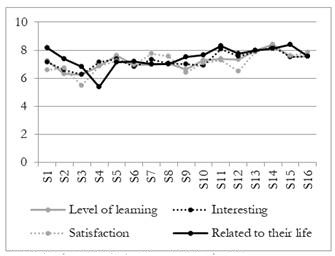

Level of satisfaction and acceptability of the Adolescent Subprogram

Adolescents (n = 31) considered that their level of learning of session contents was satisfactory (M = 7.36), and affirmed that the sessions were interesting for them (M = 7.94). In the same way, they were satisfied with how the sessions were carried out (M = 7.79), and they agreed that the topics covered were related in some way to their lives (M = 8.31). The overall evaluation of the program was positive, as shown in Figure 1. This assessment was maintained throughout the program, although it should be noted that the level of satisfaction was lower in session 3 (Conceptualization of violence) than in the other sessions. In session 4 (Substance use) they stated that the content of the session was not very related to their lives.

Effects of the program in the medium term

Youth-to-parent aggression

YPA was assessed on the basis of parental self-reports (n = 49; 18 fathers and 31 mothers), with parents in the post-intervention condition perceiving less psychological YPA towards them than in the pre-intervention condition (M = 2.17 and M = 2.92), t(18) = 3.67, p = .002, d = .87, 95% CI (0.31, 1.17), the same being true for mothers (M = 2.6 and M = 3.32), t(30) = 3.56, p = .003, d = .65, 95% CI (0.25, 1.17). Furthermore, physical YPA towards mothers also decreased (M = 1.39 and M = 1.81), t(30) = 3.25, p = .003, d = 0.61, 95% CI ( .16, .69).

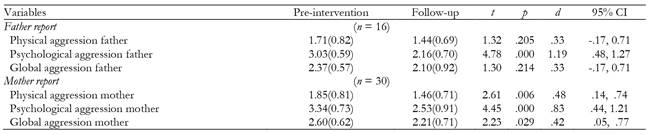

When comparing post-treatment and follow-up scores (n = 45; 16 fathers and 29 mothers), no significant differences were found in all the measures of YPA. As shown in Table 2, in the comparison between pre-intervention and follow-up (n = 46; 16 fathers and 30 mothers), violence decreased significantly in all cases (p < .05) except physical aggression towards fathers. The most relevant effects observed correspond to psychological aggression towards fathers (d = 1.19) and towards mothers (d = 0.83).

Variables related to clinical symptomatology of adolescents and family conflict perception

In the post-intervention condition in comparison with pre-intervention (n = 22), adolescents manifested a lower level of irrational beliefs (M = 2.34 and M = 2.59), t (22) = 2.49, p = .021, d = 0.47, 95% CI (-.39, 0.51), and blame proneness (M = 3.04 and M = 3.41), t (22) = 2.04, p = .021, d = 0.54, 95% CI (.04, .47). Moreover, the level of depressive symptoms (M = 1.77 and M = 2.01), t (22) = 2.13, p = .045, d = .47, 95% CI (.01, .65) and self-esteem dimension (depression subscale) also decreased (M = 1.79 and M = 2.24), t (22) = 2.50, p = .020, d = .59, 95% CI ( .08, .82).

Between the post-intervention and follow-up evaluations (n = 17), irrational beliefs and depressive symptoms remained stable at follow-up. However, adolescents manifested a lower level of emotional instability (M = 2.54 and M = 2.78), t (17) = 2.42, p = .028, d = .37, 95% CI (-.03, .43). The level of overall empathy increased between the post-intervention and follow-up, (M = 3.28 and M = 2.90), t(17) = -4.18, p = .001, d = -.58, 95% CI (-.56, -.18), as did the empathic concern (M = 3.18 and M = 2.85), t (17) = -2.66, p = .017, d = -.44, 95% CI (- .59, - .07), and perspective taking dimensions (M = 3.40 and M = 2.98), t(17) = -3.57, p = .003, d = -.56, 95% CI (- .66, -.17).

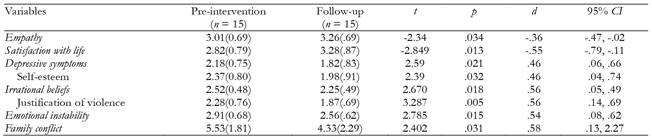

The comparisons between pre-intervention and follow-up evaluations (n = 15) are shown in Table 3. A medium effect of the program was found in five psychological variables of adolescents and their family conflict perception. A significant increase was observed in the satisfaction with life (d = -.55), and overall empathy (d = -.36) of adolescents. At the same time, there was a decrease in overall their irrational beliefs (d = .56), emotional instability (d = .54), depressive symptoms (d = .46), and perception of family conflict (d = .58). The positive effect on family environment was only found one year after starting the intervention program, but no effect was found short term.

Discussion

A family-focused approach to YPA is considered crucial to addressing the underlying intra-family conflicts and the often entrenched communication difficulties that are likely to perpetuate family violence. The evaluation of EI-YPA in previous studies revealed that many of the adolescents and their parents benefited from the program in certain ways short term (e.g. Arnoso et al., 2021; Ibabe et al., 2021) because behavioural changes and clinical symptoms of adolescents and parents were observed, and relationships between family members showed clear improvements. Nonetheless the current study is a welcome addition to a very small body of research evaluating intervention programs for YPA situations. Earlier quantitative studies of EI-YPA have found it to be a promising YPA intervention program. However, the present study was the first to evaluate mid-term effects of the EI-YPA program (Ibabe et al., 2019) on the behaviour of adolescents and the level of program acceptability.

The first aim was to analyze the level of satisfaction and acceptability of the Adolescent Subprogram. It should be noted that of the 37 adolescents, 6 did not complete the program, either being referred to the Provincial Council of Álava (n = 3) because YPA developed towards greater severity and serious cases are not managed by Vitoria-Gasteiz city council, or for personal reasons (n = 3) (fatigue or low motivation).

Of the 31 adolescents who completed the program, all the analyzed indicators show that participants valued the subprogram very positively, with average scores above 7 points out of 10. An increase in the mean scores was observed from the first sessions to the last. Two sessions stand out as being less valued and as having little to do with adolescents' lives, those related to the conceptualization of violence and to substance use. These less positive assessments could be explained by the fact that the first discusses the symptoms for which they are in treatment and the second session shows a reality that some adolescents may wish to hide. These results are consistent with previous studies based on the level of acceptability of Parent Subprogram (Ibabe et al., 2021), and Family Subprogram (Arnoso et al., 2021) of EI-YPA, and with the observations of the therapists (Asla et al., 2020).

The second objective was to check whether, after program completion and in the follow-up phase, YPA had decreased, both physically and psychologically. Based on the information provided by parents, psychological aggression towards both parents and physical aggression towards mothers had decreased at the end of the program. Likewise, it can be seen that the improvements were maintained six months after the end of the program, and that the levels of psychological YPA towards the parents and physical YPA towards mothers are lower than those presented at the beginning of the program. No significant differences were found in the case of physical YPA towards fathers, probably due to the small sample size because a moderate effect size was observed. These data are similar to the results obtained in previous studies with a smaller sample (Arnoso et al., 2021; Ibabe et al., 2018; Ibabe et al., 2021).

Regarding the third objective, it was found that in the follow-up phase, adolescents showed positive changes in variables related to clinical symptomatology. Specifically, emotional instability, depressive symptoms (overall and self-esteem dimension) and irrational beliefs (overall and justification of violence) decreased one year after starting EI-YPA program, while empathy and life satisfaction increased. These variables presented medium effect size. The advantage of effect size is their independence from sample size. Moreover, it is interesting to note that in the post-intervention condition, the level of irrational beliefs and depressive symptoms was significantly lower than in the pre-intervention condition. Taking into account the contents covered in the program over six months, it may take some time for significant changes to be observed in adolescents, showing the necessity of understanding and maturing over time of what has been learned. This would justify and explain that certain changes were not statistically significant just after the intervention, and that the effects only became visible in the follow-up phase. The results obtained with five medium-term intervention groups on YPA support the initial evidence obtained in the previous studies of the short-term IP-YPA program (Ibabe et al., 2018; Ibabe et al., 2021). With respect to clinical symptomatology of adolescents, in a previous study positive effects were only found on irrational beliefs and self-esteem (Ibabe et al., 2021).

In relation to family environment, the present study adds that adolescent perception of family conflict decreases in the medium term, with a medium effect size, while no effect was found in the short term. Previous studies indicated a positive evolution of family relationship quality, as found during the EI-YPA program development according to child report and parent report (Asla et al., 2020; Ibabe et al., 2021). Changes in the closeness of the child-parent relationship during treatment were observed as the program progressed, and the level of family conflict was significantly lower at the end of intervention. The reduction in family conflict is clearly evident in the medium-term, and therefore, improvements in parent-child relationships and communication.

It would be interesting to compare the current results with what has been found in evaluation report of similar intervention programs. Although YPA is a critical problem facing families, law enforcement, the juvenile justice system, and mental health professionals, specific interventions for this problem are scarce (Nowakowski & Mattern, 2014) and lack a sufficient amount of empirical support (O'Hara et al., 2017). Apart from the evaluated program, only two programs have published the evaluation reports (Nonviolent Resistance, and Step-Up) (Coogan & Lauster, 2015; Routt & Anderson, 2011) but the evaluation is very superficial. The Step-Up program was developed in King County, Washington, and utilizes a cognitive-behavioural and skills-based approach to reduce violence. The evaluation report showed promising results at 12-month follow-up, including a lower percentage of offenses (10% in Step-Up group; 20% in comparison group) (Routt & Anderson, 2011). Parents who participated in the nonviolent resistance training showed reductions in parental helplessness and escalatory behaviours, as well as improvements in perceived social support (Weinblatt & Omer, 2008). Moreover, significant reductions in problem behaviour in foster children and in parenting stress were found (Van Holen et al., 2018).

The biggest limitation of the study is the small sample size and the absence of an equivalent control group. Due to the reduced sample size of adolescents, it was not possible to analyse the potential differentiated patterns of sons and daughters. Despite not having a control group, this fact does not invalidate the results obtained in the present study for four reasons. First, considerable evidence of positive effects was found. The shortcomings are balanced to some extent by the assessment of outcome variables at three key moments (pre- and post-intervention, and follow-up) together with the inter-session evaluation of program acceptability. Second, efficacy on behavioural variables (physical and psychological violence), cognitive variables (empathy, irrational beliefs), emotional variables (satisfaction with life, depressive symptoms, emotional instability), and family environment (such as family conflict) was found. Third, information from different sources (adolescents, mothers and fathers) is shown. Fourth, adolescents stated a high level of satisfaction and acceptability of the program. A further limitation of the study is the potential experimenter bias, because evaluators knew the experimental condition of participants and this fact could intentionally or unintentionally affect data, participants, or results in the study. Despite these limitations, the present study has the strength of being a pioneering program intervening on an emerging family problem in a social services context. It is a program that meets the needs of adolescents, parents and the family system. It should be noted that adolescents as a group are usually identified as the cause of conflictive family situations and as being reluctant to participate in programs. That this program manages to ensure their participation and obtains positive evaluations is worth mentioning.

In conclusion, positive effects were found in the medium-term regarding the impact on the mental health and wellbeing of adolescents, as well as their family conflict perception. Additionally, program acceptability among adolescents can be considered satisfactory, with relevance to their lives showing higher scores than the other measures. In future studies, it would be useful to check whether these results are confirmed with a larger sample and to identify the predictors for success of the program in adolescents, with the aim of recommending its application in the field of child protection and child and youth health services. It would also be interesting to study the possibility of adapting this program to a virtual format in case of lockdown situations due to pandemics. Previous experiences have shown that some online resources for parents have been useful because they provide anonymity and avoid stigmatization suffered by some families with this family problem (Holt, 2011). There is a lack of community awareness about the extent of YPA (Campbell et al., 2020). Thus, an awareness campaign on YPA, similar to that regarding adult family violence is needed to educate the community (Kehoe et al., 2020). These interventions and campaigns could subsequently reduce the chances of family breakdowns and associated downstream problems such as youth homelessness, disengagement from schooling, unemployment, substance abuse, and increased risk of offending for youth (Kehoe et al., 2020).