Introduction

The self is a topic frequently discussed in psychology. It is stated that the self is formed in a social context, not by itself (Maji & Dixit, 2020). One of the most important social contexts affecting the self is the phenomenon of gender. The fact that expectations of the society from men and women are different brings with a different shape of their selves. Berktay (2004) states that gender emerges when the biological difference between men and women is transformed into an unequal, hierarchical difference in culture. The formation of the self in women takes place in the context of relationships, interactively with the phenomenon of gender, with others (Gilligan, 1993).

In line with gender roles, women are taught that they should be satisfied, suppress their anger, not to say no, and make people happy and comfortable. This situation may cause women to move away from their true selves and to construct their selves in accordance with the ideal female image, thus including gender roles (Gilligan, 1993). The effort to get away from the real self and to be the ideal woman can cause women to silence their own selves. Because gender inequality in the traditional female role dictates that a man's needs are more important than women's needs and that the woman should choose what the other wants to do, not what she wants (Jack & Dill, 1992). That is, self-silencing is created by norms, values, and images that dictate that women should be gentle, selfless, loving, etc. (Jack & Ali, 2010). Women who shape their self within the framework of norms, values, and images dictate how a woman should be suppressed their own emotions, thoughts, and actions. This situation is explained by the self-silencing theory in the literature.

The self-silencing theory emerged as a result of studies conducted with women who were depressed (Jack & Dill, 1992). Motivation to silence oneself mostly stems from an attempt to undermine a gender role encoded by passivity, bodily shame, fear, vulnerability, and courtesy (Jack & Ali, 2010). This theory argues that the woman who is forced to act in accordance with the ideal femininity norms of the society actively suppresses her own thoughts and feelings in order not to conflict with the people she is in contact with (Jack & Dill, 1992). Self-silencing is a cognitive self-scheme. The basis for the adoption of this scheme is the attempt to create and maintain safe, intimate relationships by silencing certain thoughts, feelings, and actions of the person. This situation can accelerate a general self-negation through the gradual devaluation of one's own thoughts and beliefs (Ali et al., 2000). In other words, self-silencing may lead to negative consequences such as low self-esteem, loss of self, susceptibility to depression, etc. (Jack & Dill, 1992).In the literature, there are studies showing that self-silencing is associated with psychological disorders such as depression (Ahmed & Iqbal, 2019; Flett et al., 2007; Jack, 1991; Kosmicki, 2017; Little et al., 2011; Tariq, & Yousaf, 2020; Zoellner & Hedlund, 2010), eating disorders (Buchholz et al., 2007; Frank & Thomas, 2003; Geller et al., 2000, Lieberman et al., 2001), anxiety (Kosmicki, 2017), etc. in women.

Self-silencing has various dimensions and the Silencing the Self Scale (STSS) developed within these dimensions. One of these dimensions is evaluating and judging oneself through someone else's views, that is, Externalizing Self-Perception (ESP). Care as Self Sacrifice (CSS), on the other hand, involves seeing the needs and desires of the people they care about and with whom they are in a relationship as a priority over their own wants and needs, and perceiving doing things for themselves as selfish. The third dimension of self-silencing is the tendency not to express oneself and block their actions in order to prevent possible conflicts, retaliation and loss in relationships and it has been named "Self Silencing (SS)". The fourth dimension is called the "Divided Self (DS)" and this dimension indicates the hiding of feelings and thoughts from the person in the relationship and difference between false outer self and inner self (Jack & Ali, 2010).

When the studies on the adaptation of STSS to Turkish were examined, it was seen that it was adapted into Turkish by Kurtiş (2010) for the first time in order to measure self-silencing in romantic relationships for women. However, due to size and characteristics of the sample group, Birtane-Doyum (2017) re-adapted it to Turkish in the context of romantic relationships for both men and women. However, studies showing that the scale has poor construct validity in male samples (Remen et al., 2002) and shows a different factor structure (Cramer & Thoms, 2003) revealed the necessity of adapting the scale to measure self-silencing in women. The STSS, which was developed by Jack and Dill (1992) based on the theory of self-silencing, was normally developed to measure self-silencing in the context of romantic relationships. However, it is known that silencing the self in women can occur not only in romantic relationships but also in all relationships. For this reason, it is observed that it is also adapted to measure friendship relationships (Dainow, 2014), workplace relationships (DeMarco, 2002; DeMarco et al., 2007), and students' relationships with teachers (Patrick et al., 2019). Considering that self-silencing behavior occurs within the framework of conforming to gender roles in women and this behavior can occur not only in romantic relationships but also in relationship practices in all areas of life. The purpose of this study is to adapt the “STSS” to Turkish for women, not only in the context of romantic relationships but also in general relationships.

Method

Participants

In the study, data were collected from two study groups. The first study group consists of 496 women aged from 18 to 53. Of these women, 25.6% have high school or lower level degree, 3.2% have a associate degree, 52.8% have an undergraduate and 18.3% have a graduate degree. Data were collected from this research group to calculate the construct validity of the scale and Cronbach Alpha. The second study group consists of 60 women aged from 18 to 22. Data were collected from this group for test-retest reliability. This group was chosen from university students in order to reach them again.

Data Collection Tools

The STSS and Personal Information Form were used as data collection tools in the study.

- Silencing the Self Scale: The scale consists of 31 items and its responses range from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The scale is a five-point Likert type. Five items (1.8, 11, 15, and 21) in the scale are reverse items. The scale consists of 4 sub-dimensions. These dimensions are “ESP” (6 items), “CSS” (9 items)”, “SS” (9 items), and “DS” (7 items). Study group consists of university students, pregnant women and women staying in women's shelters for the original form of scale development research. Cronbach's alpha scores for the research groups respectively were calculated as .75, .79, and .79 for ESP sub-dimension; .65, 60 and 81 for the CSS sub-dimension; .78, .81 and 90 for the SS sub-dimension; .74, .83, and .78 for DS sub-dimension and .86, .84, and .94 for the total scale. Test-retest correlation coefficients of the scale were calculated as .88, .89 and .93 for the three research groups, respectively (Jack & Dill, 1992).

- Personal Information Form: The form prepared by the researcher was used to collect demographic information of the participants.

Data Collection

During the research process, the data were collected via Google form, by contacting the participants by phone and e-mail. Volunteering was taken into account in the data collection process.

Data Analysis

The first and higher-order Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) techniques were used to verify the structure of the scale. First-order CFA was made to verify the 4-factor structure. Higher-order CFA which is a technique of interpreting various factors by aggregating a construct under a common higher-order factor (Gould, 1987), was employed to determine if the resulting subscales are components of silencing the self. Moreover, Cronbach's Alpha and test-retest were applied for the reliability of the scale.

Results

Scale Adaptation Process

During the scale adaptation process, first of all, permission to use the scale published by Dana Crowley Jack, one of the developers of the scale, was obtained. Then, studies were conducted for the language validity, construct validity, and reliability of the scale. These processes and results are summarized below.

Language Validity

The scale was first translated from English to Turkish by 5 experts (3 academic staff in the psychological counseling and guidance department, 2 academic staff in the English department) who are proficient in both Turkish and English. The Turkish form of the scale was created by comparing the translations obtained and adopting the translations considered to be the most understandable for each item. The pilot application of the form was carried out on a group of 35 second-year undergraduate students from the psychological counseling and guidance department and an application form was created by correcting the expressions in some items of the scale in line with the feedback from the students.

Structure Validity

It was decided to perform CFA in order to ensure the construct validity of the adapted scale. In general, it is more appropriate to use the CFA technique to test an existing structure or theory (Güngör, 2016). Important assumptions that should be tested in order to make CFA are univariate and multivariate outliers. To investigate univariate outliers, the z-value for each observed variable must be between +3.29 and -3.29 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). Univariate outliers were not found in the analysis. During the investigation of multivariate outliers, Mahalanobis distance was calculated. Distribution for this distance displays a distribution compatible with the chi-square distribution at x2. Forty-nine observations above the critical value (X2(31, p< 0.001) = 52,19) were excluded from the analysis due to multiple outliers.

First and Higher-order CFA Results

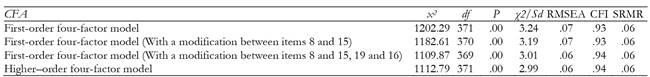

When the fit values obtained as a result of CFA were examined (χ2 / df = 3.07); RMSA = .06; CFI = .93; NFI = .90) these values were observed to be within acceptable limits. However, when the t values of the items were examined, it was observed that the t values of the 1st and 11th items, which were stated to be structurally incompatible, although they were theoretically compatible with the scale in the original scale, were also found to be meaningless in this study. The analysis was repeated by removing the 1st and 11th items on these results.The goodness of fit indices obtained as a result of the first and higher-order CFA applied in this framework and recommended to be reported (Kline, 2016) are presented in Table 1.

When the fit indices in Table 1 were examined, it is observed that χ2 / Sd value is 3.01 for the first-order and 2.99 for the higher-order CFA, and this value is less than the acceptance limit of 5 (Cokluk et al., 2014; Sumer, 2000). RMSEA, which is value of .08 and smaller indicates a good fit (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001) were computed as .06 for both the first and second-order CFA. CFI of .90 and above that indicates a good fit (Sumer, 2000), is .94 as well as SRMR value of .08 and smaller showing a good fit was 0.06 for both the first and higher-order CFA. When the fit indices emerging within this framework were examined, it is possible to say that the fit between the model and the data is sufficient.

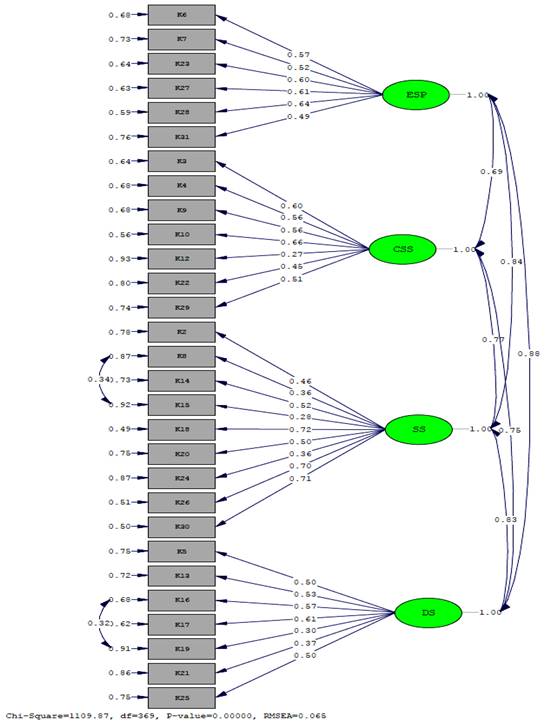

The results of the first-order CFA are presented in Figure 1.

As seen in Figure 1, the standardized solution values range from .49 to .64 for Externalizing Self-Perception, .27 - .66 for Care as Self-Sacrifice, .28 - .72 for Self-Silencing, and .30 - .61 for the Divided Self sub-dimension. Standardized solution values give an idea of how well each item (observed variable) represents its latent variable (the factor to which it belongs). When the values were examined in the figure, it has been observed that there are two items (12 and 15) that give a load below .30. However, since the t values of these items are also significant and the items are theoretically compatible with the structure, it was decided to keep them in the scale.

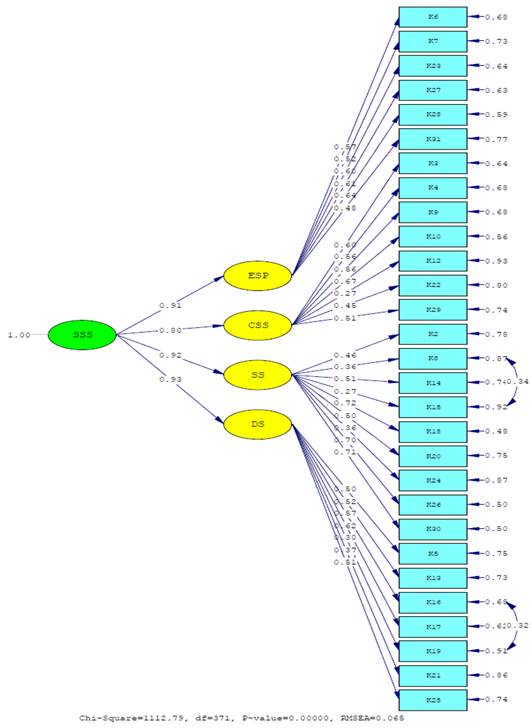

The standard solution values of the higher-order CFA are shown in Figure 2.

The standardized solution values of the higher-order CFA are shown in Figure 2. When the diagram and the obtained fit values were examined, it is revealed that it is also appropriate to get a total score from the scale.

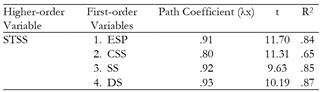

The path coefficients (λx), t and R2 values between the first-order latent variables in the model and the higher-order variable are given in Table 2.

As it can be seen in Table 2, the highest relationship (.93) with STSS belongs to the DS sub-dimension, and the lowest (.80) belongs to the CSS sub-dimension. Relationship between the higher-order variable and all first-order variables was found to be significant (p < .00). Variance in the higher-order variable in the model is explained by the DS (87%), SS (85%), ESP (84%) and CSS (65%), respectively. According to these results, it has been confirmed that these dimensions are components of the STSS.

Reliability of the Scale

Cronbach Alpha and test-retest techniques were used for the reliability of the scale. In the reliability studies, Cronbach Alpha and test-retest coefficients were calculated as .89 and .84 for the entire scale, .73 and .79 for the ESP sub-dimension; .71 and .63 for the CSS sub-dimension; .76 and .72 for the SS sub-dimension and .70. and .79 for the DS sub-dimension.

Scoring and Interpretation of the Scale

The Turkish Form of STSS consists of 29 items and 4 sub-dimensions. Items 8, 13, 15, 21 and 31 in the scale are scored reverse and other items are scored straight. The scale is 5-point Likert type (5 = I totally agree, 1 = I strongly disagree). The scale gives points on the basis of both total score and sub-dimensions. High scores on the scale indicate that the level of self-silencing is high. Items 1 and 11 were excluded from the scale because they were incompatible with the structure, similar to the original scale. These items are included in the CSS sub-dimension of the original scale and are reverse-scored.

Discussion

Within the scope of the research, evidences were reached that STSS, which was adapted to Turkish, is a valid and reliable measurement tool. For example, in the first-order CFA, it was observed that the scale displayed a 4-factor structure in accordance with its original structure, and with the higher-order CFA, these dimensions were STSS components and the fit indices were within acceptable limits. These results show that the scale has a counterpart in Turkish culture and indicates a similar structure.

In this study, item 1 (I think it is best to put myself because no one else will look out for me) and item 11 (In order to feel good about myself, I need to feel independent and self-sufficient) were excluded from the scale because they were incompatible with the structure and t values were meaningless. In the original form of scale, it was observed that these items were incompatible with the structure (Jack & Dill, 1992), and that these items were also removed from the scale in the studies conducted by Kurtiş (2010) and Birtane-Doyum (2017).

It was observed that the Cronbach alpha score of the scale and its sub-dimensions ranged from .89 to .70. These findings are similar to the values obtained from the original scale (Jack & Dill, 1992). It is stated that Cronbach's Alpha score is excellent when .90, good when .70 ≤ α < .90, acceptable when .60 ≤ α < .70, weak when .50 ≤ α < .60, unacceptable when it is .50 and below (George & Mallery, 2003). When the findings obtained within this framework were examined, the Cronbach Alpha scores are in the good category for the total score and sub-dimensions of the scale.

Test-retest correlation results of the scale and its sub-dimensions were observed to have values between .84 and .63. For psychological tests, the test-retest correlation coefficient is between .40 and .59 as medium, .60.- .74 good, and .75 and above as excellent (Cicchetti, 1994). When the results obtained in this framework were evaluated, the test-retest correlation coefficients are excellent for STSS, ESP and DS sub-dimensions, and good for CSS, and SS sub-dimensions.

Limitations

In this study, the adaptation of STSS was conducted with women from the normal population aged between 18 and 53. Therefore, if it will be used in another group, it is necessary to conduct validity and reliability studies. In original of the scale, for item 31 (I never seem to measure up the standards I set for myself), if the "Agree" and "Strongly Agree" options were selected, the participants are asked to give at least three examples of the standards they felt they could not reach (Jack & Dill, 1992). Since this study was a scale adaptation study, the participants were not asked to give examples of standards that they could not reach.

Conclusion

Within the scope of the research, psychometric evidence was obtained that scale, which was adapted to Turkish, is a valid and reliable measurement tool. These results show that the scale has a counterpart in Turkish culture, indicates a similar structure and can be used in future studies. It is thought that adapting the scale not only to romantic relationships but also to general relationships increases its usefulness. It is thought that the adaptation of a valid and reliable tool that measures self-silencing as a concept that is at the root of many psychological difficulties in women, especially depression, makes an important contribution to the field of mental health.