Introduction

School bullying can be understood as a repetitive situation of intentional aggression between peers in which there is an imbalance of power so that the victim cannot defend him/herself on his/her own from the aggressor or aggressors. It also involves different types of behaviors (e.g., physical, verbal or social aggression), that can occur offline or online (Armitage, 2021; Olweus, 1993). In the present paper we will focus on traditional or offline bullying. Acquiring a complete understanding of this phenomenon is crucial because many studies have shown important relationships between bullying in childhood and physical, mental and social health outcomes, not only in victims but also in bullies (Gini & Pozzoli, 2009; Holt et al., 2015; Moore et al., 2017). Furthermore, the consequences of bullying in bullies and victims extend into adulthood, for example, in terms of psychopathology (Armitage, 2021).

Factors influencing bully perpetration

In a meta-analysis Cook et al. (2010) identified 13 individual and contextual factors that predict bullying perpetration (gender, age, externalizing and internalizing behaviors, self-related and other-related cognitions, social problem solving, academic performance, family and home environment, school climate, community factors, peer status, and peer influence). In line with these factors, the present study examines bullying behavior in relation to sex and educational stage.

Prior research suggests that bullying perpetration could increase during childhood and peak during early adolescence (Tsaousis, 2016). Cook et al. (2010), in a meta-analysis including children aged 3 to 18 from 153 studies, found a positive significant and weak relationship between age and perpetration. Similarly, the HBSC report (which includes children aged 11, 13 and 15) on bullying informs that bullying perpetration tends to increase with age in most of the countries, with some exceptions (Inchley et al., 2020). On the other hand, children's conception of bullying could evolve as children grow older by including ideas related to repetition, intentionality (Solberg and Olweus, 2003) or indirect aggression (Björkqvist et al., 1992).

Research usually reports a higher prevalence of bullying perpetrators in boys than in girls (Cook et al., 2010; Inchley et al., 2020; Menesini & Salmivalli, 2017; Smith et al., 2019; Tabet et al., 2019). These gender differences may result from learned behavior and gender socialization processes received during childhood (Akers & Jennings, 2015; Semenza, 2019). However, research indicates that boys are not necessarily more aggressive in all types of bullying: they perpetrate aggression using more instrumental and physical methods compared to girls, who are more likely to engage in more indirect forms of aggression (Card et al., 2008; Carbone-Lopez et al., 2010). In addition, it has been observed that being a victim of bullying or feeling insecure at school were significant risk factors for later bullying (Shetgiri et al., 2012; Walters & Espelage, 2018; Walters 2020). Walters & Espelage, 2018) analysis in middle school youth concluded that being a victim of bullying caused a cognitive-affective state of hostility in victims, which subsequently increased the likelihood of bullying others or, in other words, that victims of bullying learned to bully from being bullied themselves.

Self-admission of being a bully

Hwang et al. (2017) compared peer reports with self-reports of being a perpetrator of bullying in adolescents in 7th and 8th grade (from 12 to 15 years). They found that from the students rated as bullies by their classmates only 19.6 % saw themselves as bullies. These authors found that adolescents who were aggressors according to both themselves and their peers showed more externalizing behaviors in a follow-up evaluation compared to non-aggressors and to aggressors nominated only by their peers or by themselves.

In another study, Cornell and Brockenbrough (2004) also found, in students from 6th to 8th grade, a low agreement between peer-nominations (or teacher-nomination) of being a bully perpetrator and self-reports. While 33 % of students received at least one peer nomination as bully (17 % at least three nominations), and 8 % a teacher nomination, only 3.6 % of students self-reported bullying others once or more times per week. There was a poor correspondence between peers and teachers identification of bullies with self-reports; however, peer and teachers nominations showed moderate correlations (r = .52). On the other hand, they found larger correlations between discipline outcomes with peer or teacher nominations than with self-report data. However, in a later study Branson and Cornell (2009) found independent support for the validity of both measures.

Cole et al. (2006) studied the relationship between identified bullies (either by self-report or by peer nomination) and aggressive behaviors. They found that identified bullies showed significantly higher levels of different types of aggressive behaviors (physical, verbal and social) compared to non-bullies. Furthermore, they informed that self-reported bullies had higher frequencies of physical, verbal and social bullying than peer-nominated bullies. However, their study only included 9 self-reported bullies. Also, they did not inform whether all different sub-types of aggressive behavior (e.g., direct verbal aggression vs indirect verbal aggression) were connected to bully identification, or whether some sub-types were more connected than others. Looking deeper into this issue would help us to identify which aggressive behaviors are more connected to admitting having bullied others. On the other hand, Cole et al. found that self-reported bullies were more likely than peer-nominated bullies to endorse positive attitudes toward aggression, although we don’t know whether this attitude plays a role in the self-admission.

In the case of victims, research suggests that children are reluctant to label themselves as “victims”, even if they do report a certain amount of victimization behavior (Sidera et al. 2020), possibly due to the stigma associated with it (Sawyer et al., 2008). In this regard, Greif & Furlong (2006) suggest that asking individuals to assume a label of victim demands more than a description of behavioral experiences, as it involves an interpretation of the psychological and social meaning of victimization. In the study by Sharkey et al. (2015) victims who accepted being victims had a lower psychosocial functioning than those who denied it. In this sense, the label of being a victim might be associated to being a weak person, and might involve a general negative identity.

The present study

There are a few studies in primary school children which have analyzed the self-admission of being a bully in relation to the different types of aggressive behaviors conducted by children. Hence, the objective of this study is to understand further the relationship between children's aggressive behaviors in bullying situations and their self-admission of being a bully.

As children's bullying behaviors or conceptions may be affected by factors such as sex and educational level, these variables have been considered when analyzing this relationship. The study by Cole et al. (2009) found that nine self-identified bullies had higher levels of aggressive behaviors compared to non-bullies. However, they had a very small sample and did not study the different sub-types of aggressive behavior.

In the present research we want to study which of the different sub-types of aggressive behaviors are more connected to the self-admission of being a bully. We hypothesize that the different types of aggressive behaviors will be connected to bully self-admission. These results should help us to understand better why some children are more reluctant to accept themselves as bullies than others.

Method

Participants and study design

The study followed a cross-sectional design with an ex post facto approach (Montero & León, 2007). A sample representative of primary school students from 3rd to 6th grade from Catalonia (a region in the North-East of Spain) was selected through stratified random sampling, with a confidence level of 95% and a sampling error of 1.4%. The type of school (public Vs private), the size of the school (schools with fewer than one class per grade, with one class per grade, or with more than one class per grade) and the territorial area of the Department of Education (Catalonia is divided into 10 educational areas) were used as representative criteria. The number of students in the population under study (N = 325.766) was extracted from the Directory of educational centers of the Department of Education of the Catalan government in 2018.

A total of 4646 students from 3rd to 6th grade of primary school participated in the study (49.1% were girls). The age range varied from 7 to 13 years (M = 10.16; SD = 1.17). Participants were grouped into the educational stages in which they belong according to the Spanish educational system: Middle stage, which includes 3rd and 4th grade (48.9 % were girls; M = 9.16 years; SD = 0.65), and the Superior stage, which includes 5th and 6th grade (49.2 % were girls; M = 11.10 years; SD = 0.66).

Instruments

We administered the following questionnaires to the participants:

-

European Bullying Intervention Project Questionnaire (EBIPQ) (Ortega-Ruiz, Del Rey, & Casas, 2016).

This self-report questionnaire consists of 14 items (7 for victimization and 7 for aggression) about children's behavior in the previous two months. The types of behaviors it includes are physical aggression, direct and indirect verbal aggression, threatening others, robbing or breaking others’ objects, excluding or ignoring others, and spreading rumors. Children have to respond about the frequency of the described aggressive behaviors using a 5-point Likert scale: 0 = No; 1 = Yes, once or twice; 2 = Yes, once or twice a month; 3 = Yes, about once a week; 4 = Yes, more than once a week. Cronbach's Alpha for the 7 aggression items was 0.738.

-

Self-admission of being a bully

We asked children whether they had been a victim, aggressor or observer of bullying or cyberbullying. In the present study, we just focused on the self-admission of being a bully. Specifically, we asked: “Have you bullied anyone?” Children had to mark ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Those who responded ‘yes’ were considered as having admitted of being a bully.

Before responding these questionnaires, children were asked their sex (boy or girl), date of birth, and grade.

Procedure

We contacted the Department of Education to obtain permission to conduct the study. During the 2018-2019 school year (from December of 2018 until April of 2019), data were collected in a total of 41 schools. Families were informed of the objectives of the study and their informed consent was obtained. Questionnaires were administered in paper (except for 10 group classes who responded online) mostly by researchers involved in the research project, except for five schools who preferred to administer the questionnaires themselves. Just before administering the questionnaires children were provided with an oral description of bullying, and then they chose whether they wanted to respond in Catalan or Spanish. Children were given an envelope that they could use to deliver the questionnaire to the adult and preserve anonymity.

Data analysis

Children were classified as bullies using the criteria from Romera et al. (2017), who used the same questionnaires as in our study. Like them, we considered as bullies the participants who obtained a minimum frequency of "Once or twice a month" in any of the EBIPQ aggression items. Moreover, following García-Fernández et al. (2015), participants with a minimum frequency of “More than once a week” in at least one item of the test were considered frequent bullies. The same criteria were used for victimization items in order to identify victims and frequent victims, and therefore differentiate pure bullies from bully/victims, and pure frequent bullies from frequent bully/victims.

The IBM SPSS 25 Statistics program was used to analyze data. In order to study aggressive behaviors as a function of sex and educational stage we used non-parametric statistics, as the dependent variable did not follow a normal distribution. Hence, Mann-Whitney's U was used to conduct these analyses.

In order to study self-admission of being a bully as a function of sex and educational stage we used the Chi-square test, as they are all are categorical variables.

Finally, to analyze the relationship between bullying self-admission and the different types of aggressive behaviors, a binary logistic regression was conducted.

Results

Aggressive behaviors

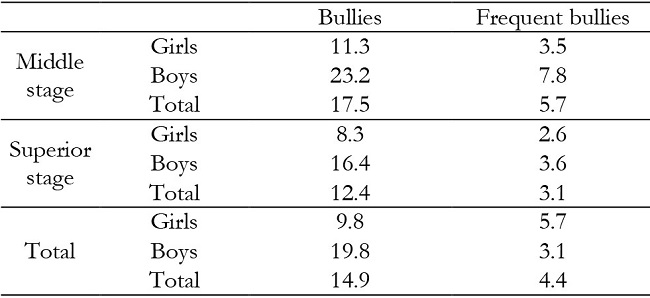

As can be seen in Table 1, 14.9 % of participants (n = 692) reached the criteria for being considered a bully. On the other hand, despite the analysis of the results section focused on pure bullies, it was of interest to know which bullies were also victims. In the group of non-victims there were a 3.5 % of bullies, while in the group of victims there were a 34.6 % of bullies. In addition, in the group of bullies 85 % were also victims.

A 4.4 % were frequent bullies (n = 202) according to their responses from the EBIPQ questionnaire. In the group of non-frequent victims, there were only a 1.6 % of frequent bullies, while the percentage was 17.4 % among frequent victims. A 69.3 % of the children who were frequent bullies were also frequent victims.

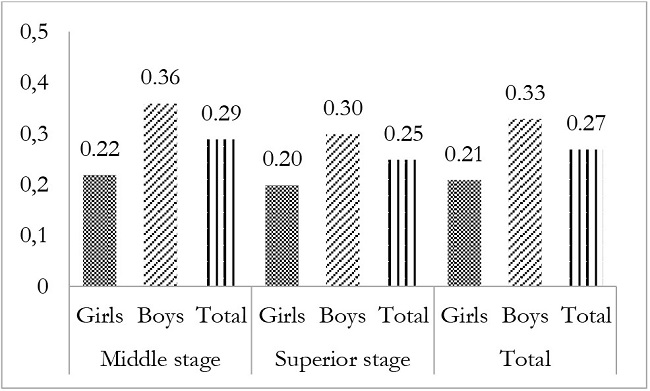

To compare children's aggressive behaviors according to sex and educational stage (see Figure 1) we used the mean scores of their aggressive behaviors (sum of scores in the 7 items divided by 7). In this way, we carried out a two-way ANOVA of educational stage (2) x sex (2).

Results showed more aggressive behaviors in boys compared to girls (Z = -12.217; p < .001) and more behaviors in the Middle aggressive stage compared to the Superior stage (Z = -2.114; p = .035). When we compared the educational stages in each sex, we found significantly higher levels of aggressive behaviors in the Middle stage compared to the Superior stage in boys (Z = -2.937; p = .003), but not in girls (p > .05). Besides, when we compared boys and girls in each educational stage we found higher scores in boys than in girls both in the Middle stage (Z = - 9,771; p < .001) and in the Superior stage (Z = -7.498; p < .001).

Self-admission of being a bully

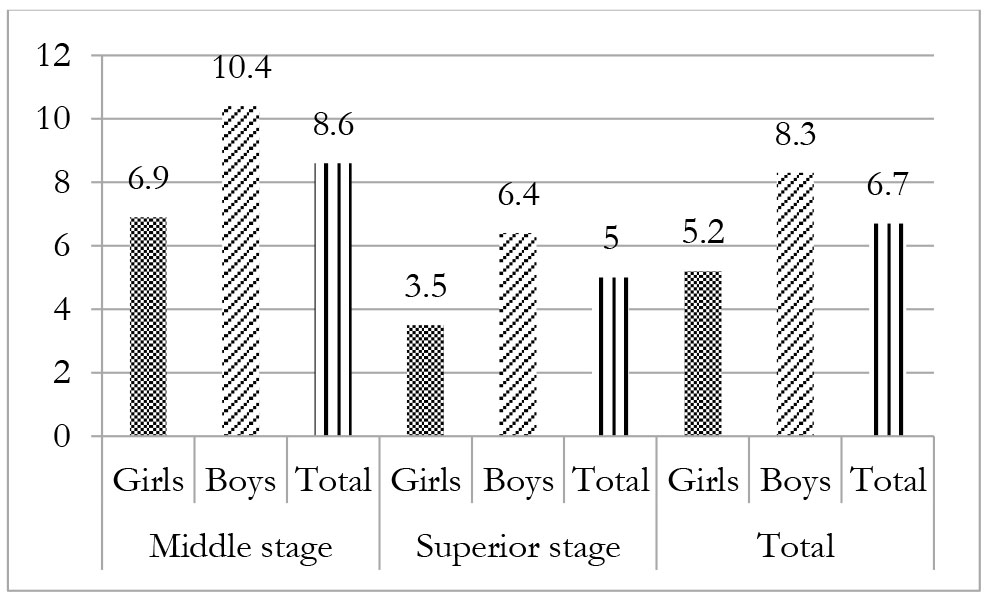

From the 4646 participants, 6.7 % admitted having been a bully. Figure 2 shows the results as a function of sex and educational stage.

We found a significant relationship between the sex variable and the self-admission of being a bully. There were more boys than girls admitting having been a bully (χ2 (1, N = 4263) = 16.833, p < .001; Cramer's V = .063). This relationship was significant both in the Middle stage (χ2 (1, n = 2074) = 7.70, p = .006; Cramer's V = .061) and in the Superior stage (χ2 (1, n = 2189) = 79.58, p = .002; Cramer's V = .066).

We found more children who admitted having a bully in the Middle stage compared to the Superior stage (χ2 (1, n = 4476) = 23.50, p < .001; Cramer's V = .072). This relationship was significant both in boys (χ2 (1, n = 2152) = 11.36, p = .001; Cramer's V = .073), and in girls (χ2 (1, n = 2111) = 12.80, p < .001; Cramer's V = .078).

Self-admission of being a bully and aggressive behaviors

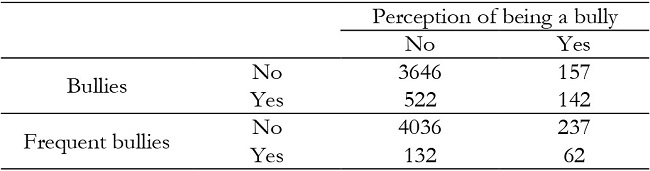

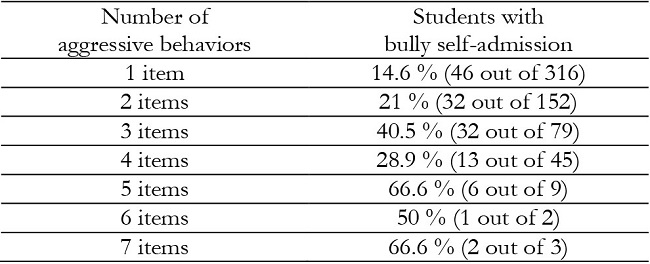

We analyzed the Self-admission of being a bully among bullies (according to children's responses in the EBIPQ bullying questionnaire) (see Table 2). The Chi-square test showed a significant relationship between being a bully and admitting it (χ2 (1, n = 4467) = 269.60, p < .001; Cramer's V = .246). Yet, we observed that only 21.4 % of bullies admitted it. The Chi-square also showed a significant relationship between frequent bullies and children's self-admission of being a bully (χ2 (1, n = 4467) = 207.28, p < .001; Cramer's V = .215). The percentage of frequent bullies who admitted being a bully was 31.96%.

When we considered the sex variable in the analysis of the relationship between being a bully and admitting it, we observed that the percentage of bullies who admitted it was similar in boys (21.4%) than in girls (21.1%). The Chi-square showed no relationship between both variables neither for the whole sample nor for the sample divided into educational stages (p > .05 in all cases). In the case of frequent bullies, there was also a higher percentage of boys compared to girls, but again the Chi-square showed no significant relationship between these variables (p > .05).

Regarding the educational stage, bullies in the Middle stage had a higher percentage of bully self-admission (23.8 %) compared to the Superior stage (18.1%). The Chi-square test showed a non-significant relationship between the educational stage and the self-admission of being a bully (χ2 (1, n = 664) = 3.2, p = .075; Cramer's V = .069). Frequent bullies in the Middle stage also had a higher perception of having been a bully (36.6 %) compared to the Superior stage (23.9 %). The relationship between these variables was also non-significant (χ2 (1, n = 194) = 3.31, p = .069; Cramer's V = .131).

Self-admission of being a bully as a function of type of aggressive behavior

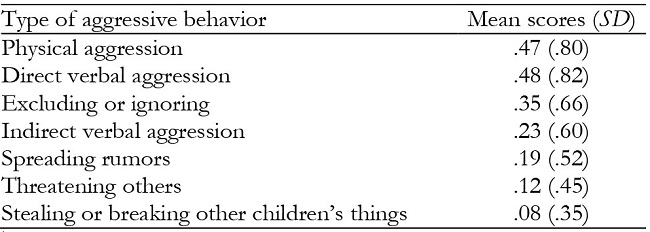

Table 3 shows the descriptive scores of aggressive behaviors of the different types of behaviors. Physical aggression and direct verbal aggression were the most frequent, while threatening others and stealing or breaking other children's things were the least frequent.

Table 3: Mean (and SD) scores of aggressive behaviors for the different types of behaviors.

Note.All scores ranged from 0 to 4.

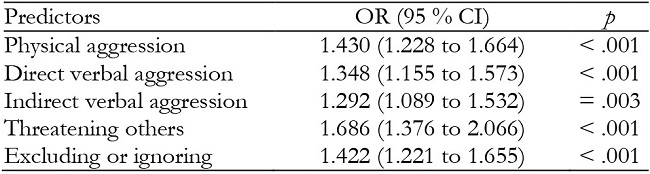

A binary logistic regression was conducted (Enter Method) in order to study which types of aggressive behaviors were the best predictors of bullying self-admission. In Table 4 can be observed that 5 out of 7 aggressive behaviors were significant predictors of bullying self-admission.

Table 4: Binary logistic regression analysis of the predictors of bullying self-admission.

Note.OR = Odds ratio; CI = Confidence interval; N = 4270; R2 Nagelkerke = .198.

Finally, we analyzed bullying self-admission according to the number of items in the EBIPQ in which children reported a minimum frequency of 2 (see Table 5). We observed that only in children who reported this minimum frequency in more than four aggressive behaviors, the percentage of children who admitted being a bully was equal or superior to 50 %.

Discussion

The main aim of this paper is to study the relationship between children's aggressive behaviors in bullying situations and their self-admission of being a bully, as well as the role that the variables of sex, educational stage, and type of aggressive behavior play in this relationship. We will first discuss our results regarding aggressive behaviors and then we will discuss their relationship with the self-admission of being a bully.

Bullying behaviors

Prior research has found that bullying perpetration increases during childhood and reaches its peak during early adolescence (Cook et al., 2010; Tsaousis, 2016). In this regard, the results of our study are partially inconsistent with prior research, as we observed more frequency of bullying behaviors in the Middle stage compared to the Superior stage in boys (not in girls). However, the effect size was low, and similar examples of declines in bullying perpetration in boys have been observed in a few countries (Inchley et al., 2020). Despite it cannot be confirmed here, our data could also be indicating a change in children's conception of bullying, which is broader in young children (Solberg & Olweus, 2003). As for sex differences, we observed more bullying behaviors in boys than in girls, both in the Middle and Superior educational stage, which is consistent with prior research (Cook et al., 2010; Inchley et al. 2020; Menesini & Salmivalli, 2017; Tabet et al., 2019).

Self-admission of being a bully

Hwang et al. (2017) observed that among the children who were considered as bullies by their peers, only 19.6 % considered themselves as bullies. This percentage is similar to the one observed in our study where we analyzed the self-admission of being a bully (21.4 %) in relation to bullies identified through children self-reported aggressive behaviors. For frequent bullies self-admission was higher (31.96%), but still low and worrying. Sidera et al. (2020) found that from the children who were considered victims of traditional bullying according to their self-reported received aggressive behaviors, 43.1 % had a perception of victim (55.4 % in the case of frequent victims). If we compare their study with ours, it seems there is even a higher reluctance from the students to consider themselves as bullies compared to consider themselves as victims. Prior studies have found lower rates of bullies when identified by self-report compared to peer-nomination (Cole et al., 2006; Branson & Cornell, 2009). In this regard, Branson and Cornell (2009) suggest that children may be unwilling to report themselves as bullies due to potential disciplinary consequences or to stigma. There is a need to study further children's reasons for not admitting bullying behaviors.

In our study we found that some aggressive behaviors predicted bullying self-admission (and especially threatening others), while other aggressive behaviors did not. Therefore, our hypothesis was partially confirmed. In this regard, it would be interesting to investigate whether some aggressive behaviors are more accepted or normalized in schools than others. Volk et al. (2012) suggest that bullying could be an adaptive strategy in competitive contexts rather than a maladaptive behavior, especially for pure bullies (bullies who are not victims). Bullying can thus provide benefits, both individually and within the group (Kun et al., 2013; Reijntjes, et al., 2013). Aggressive behaviors are accepted in the schools not only by peers but also by adults (Harger, 2019), which might help bullies to keep these benefits.

Although in the present research we did not study the consequences of considering oneself as a bully, the study by Hwang et al. (2017) found that children who were considered bullies both by themselves and by their peers showed more externalizing behaviors in a follow-up. Hence, considering oneself as a bully might be associated with more consequences for the bullies, but more research is needed in this respect.

We found a decrease with educational stage on children's self-admission of being a bully, but this decrease was not significant. Bearing in mind that the question related to the self-admission of being a bully referred to any time point, this reduction is somehow surprising. Sidera et al. (2020) also found a reduction during the same period of life in children's perception of having been a victim. In both cases it can be interpreted either as an age-related change in the conception of bullying (Smith & Levan, 1995; Solberg & Olweus, 2003), or as a decrease in the willingness to consider oneself as a bully or as a victim. Hellström and Lundberg (2020) analyzed 11- and 13-year-old students’ viewpoints of bullying and found that while younger children perceived bullying in private settings as more severe, older students found it more severe when it was described in terms of offline repetitive bullying in public settings. The authors interpreted that perhaps young students’ definitions might be more based on fear of what can happen if a child is bullied alone, while older children are more worried about the stigma and shame of being bullied in front of others. Hence, this could be an explanation for a possible higher reluctance in older children to accept being a victim, and perhaps too to accept being a bully. If older children found public bullying as more severe, perhaps older children are also more worried about their possible image as bullies in front of their peers. Moreover, Hellström and Lundberg found that repetition was a more important criterion for defining bullying in older children compared to younger children, which could also affect older children's bully self-admission, as they would only include instances of repetitive aggression. Future studies could try to study children's self-admission of being a bully taking into consideration both children's peer status and their concept of bullying.

We found more boys than girls with a perception of being a bully, but this might be explained because boys also showed more aggressive behaviors than girls. In fact, the self-admission of being a bully among bullies was similar between boys and girls.

One of the limitations of the present study is that when we asked children if they had bullied others we did not ask them how long ago it happened. This would have helped us to interpret better the relationship between bullying behaviors (in the last two months) and having the self-admission of being a bully. Regarding the evaluation of bullying, it would have been interesting to ask, for each bullying item, about the characteristics of bullying (repetition, intentionality, and power differentials), as suggested by Jia and Mikami (2018). In addition, the question we used to study bullying self-admission may have been too much direct for children; maybe using a more indirect method would have led to a higher likelihood of accepting to have bullied others. Also, we could have evaluated bullying behaviors (and bullying self-admission) through other measures such as sociometric data or peer questionnaires, which would have allowed us to compare children's self-admission of being a bully with the perception of their peers. Finally, our sample size did not allow us to study the self-admission of being a cyberbully among children who carried out cyberbullying behaviors. That would be an interesting line of research.

To summarize, our study is one of the few that has studied the self-admission of being a bully in primary school children in relation their aggressive behaviors. We found that self-admission among bullies was not affected by sex or educational stage. Moreover, children's self-admission of being a bully was low even in frequent bullies or in children who performed different types of bullying behaviors, and interestingly, self-admission of being a bully was more linked to some aggressive behaviors than to others. Determining whether children's self-admission of being a bully is related to a higher motivation to change their behavior could be helpful to educational interventions. Moreover, in our study with primary school children we found that 85 % of bullies were also victims of bullying. As being a victim of bullying has been found a risk factor for ulterior bullying behaviors (Walters & Espelage, 2018), interventions targeted at bullies should consider that bullies might also have been victims in the past.