My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The European Journal of Psychiatry

Print version ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.19 n.2 Zaragoza Apr./Jun. 2005

Changes in the attitudes towards psychiatry among Spanish medical students

during training in psychiatry

| Antonio Bulbena, M.D., MSc (Cantab).* Guillem Pailhez, M.D.** Joaquim Coll, M.D.*** Richard Balon, M.D.**** * Department of Psychiatry, Hospital del Mar, Barcelona, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona |

Key words: Recruitment, Attitudes, Enrollment, Students.

ABSTRACT - Background: To gain an understanding of the process of recruitment, studying changes in attitudes and views towards psychiatry among Spanish medical students during their fourth academic year.

Methods: A 33-item questionnaire was administered to 48 medical students before and after having completed training in psychiatry. Comparative data analysis was carried out using the Wilcoxon test.

Results: The comparison showed that there was a reduction in the number of students reporting that "psychiatrists abuse their legal power", that "for most specialists in this area, psychiatry was not their preferred choice" and that "those students interested in psychiatry are regarded as odd or peculiar". However, the view that "psychiatry is an expanding frontier of medicine" decreased among the students. The percentage of students considering psychiatry as a future career rose from 4.2% to 10.4% after training.

Conclusions: The students' opinions change with the experience of training in psychiatry and become more realistic. Alongside these changes in attitudes, there is an increase in the proportion of students willing to consider psychiatry as a future career, which suggests that there is no reduction in vocations for psychiatry among Spanish students.

Introduction

The study of the attitudes and opinions expressed by students towards psychiatry is progressively getting more and more international repercussion. This is due, in part, to the lack of residents wanting to choose psychiatry as their professional future in some countries.

In this respect, a negative attitude towards psychiatry or the psychiatrist's role has frequently been observed by a number of authors in different countries. The most common complaints relate to the lack of scientific rigor in psychiatry, the non-efficacy of treatment and the psychiatrists' low social status among physicians compared to other specialties: some of these countries are the U.S. (Lee, Kaltreider and Crouch 1995, Balon et al. 1999, Zimny and Sata 1986, Yager et al. 1982, Nielsen and Eaton 1981, Eagle and Marcos 1980), the U.K. (Calvert et al. 1999, Creed and Golberg 1987, Wilkinson, Greer and Toone 1983), Spain (Pailhez et al., submitted for publication), France (Samuel-Lajeunesse and Ichou 1985), Australia (Yellowlees, Vizard and Eden 1990, Malhi et al. 2003), Saudi Arabia (Soufi and Raoof 1992), Korea (Koh 1990) and China (Pan, Lee and Lieh-Mak 1990). Furthermore, it is accepted that there are considerable difficulties in attempting to modify these negative attitudes during the process of medical training (Calvert et al. 1999, Pan, Lee and Lieh-Mak 1990, Arkar and Eker 1997, Galletly et al. 1995).

There is some evidence that students' opinions of psychiatry improve with their experience of the subject (Wilkinson, Greer and Toone 1983, Baxter et al. 2001, Alexander and Eagles 1990). However, there is no agreement as to whether this change of attitude is permanent (Wilkinson, Toone and Greer 1983), transient (Baxter et al. 2001, Brook 1983, Burra et al. 1982), or if it could change in an unfavorable direction (Creed and Goldberg 1987, Sivakumar et al. 1986).

The academic factors that have been verified as especially important to the improvement of students' attitudes towards psychiatry are the knowledge acquisition, the awareness of the therapeutic potential of psychiatric interventions and the direct contact with patients (Alexander and Eagles 1990, Brook 1983, Burra et al. 1982, Crowder and Hollender 1981). It is also relevant to promote an influential interaction between students and psychiatrists (Zimny and Sata 1986, McParland et al. 2003) especially in an educational program integrating various medical specialties in order to instigate liaison work and contact with psychiatric outpatients (Brook 1983, Eagle and Marcos 1980).

Most studies show that a positive change of attitude increases the proportion of students considering becoming psychiatrists after their psychiatry internship (Creed and Goldberg 1987, Wilkinson, Greer and Toone 1983, Reiser, Sledge and Edelson 1988, McParland et al. 2003). However, some authors argue that better opinions need not lead to more students choosing to specialize in the subject (Alexander and Eagles 1990, Sivakumar et al. 1986) and that the improvement is temporary, with the percentage of potential candidates for psychiatry continuing to fall up until the completion of medical school (Creed and Goldberg 1987, Brook 1983, Reiser, Sledge and Edelson 1988). In the same way, students have been reported to express more negative opinions towards psychiatry during their surgery or general medicine internships (Eagle and Marcos 1980, Creed and Goldberg 1987).

Some authors (Balon et al. 1999, Garyfallos et al. 1998, Pailhez et al. 2004) state that the general opinion of psychiatry is improving considerably, together with its social image in general. However, on the other hand, according to some U.S., British and Australian studies, the number of students choosing psychiatry as their future specialty is decreasing considerably (Sierles and Taylor 1995, Balon et al. 1999, Nielsen and Eaton 1981, Creed and Goldberg 1987, Malhi et al. 2003, Sivakumar et al. 1986, Crowder and Hollender 1981, Brockington and Mumford 2002). However, it has lately increased reasonably from 3.5% in 1999 to 4.5% in 2003 in the U.S. (National Resident Matching Program 2003 Match Data). Although the causes for this decrease may not be certain, it may be presumed they are multifactorial (Sierles and Taylor 1995, Balon et al. 1999) and that the U.S. students' views and opinions towards psychiatry after their internships only partially explain the low percentage of residents in the U.S. (Balon et al. 1999).

The objective of this study is to gain an understanding of the process of choosing psychiatry as a future professional career by considering the changes in the attitudes towards psychiatry among Spanish medical students during an academic year. Our hypothesis is that the contact with the subject causes a change in the attitudes that increases the number of students wishing to specialize in psychiatry as a professional future.

Methods

The population subject to study were the students of the Hospital del Mar School, belonging to the Faculty of Medicine of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Autonomous University of Barcelona) during the academic year 1999/2000. The only selection criterion was to have done psychiatry both theoretical and practical in that academic year. In our university, the psychiatry course consists of a total of 100 hours (6 weeks during the fourth year): 35 hours of theory lessons and 65 hours of practice rotation. The practice rotation includes emergency service, outpatient consultation, and acute and chronic wards.

Using a longitudinal design, a questionnaire based on that by Nielsen et al. 1981 adapted by Balon et al. 1999 and translated from English into Catalan was administered to the students before and after completing their training in psychiatry. The Catalan translation had been previously handed to a professional translator blind to the original questionnaire, who was asked to do a back translation into English. Both English versions were compared and no differences in meaning were found.

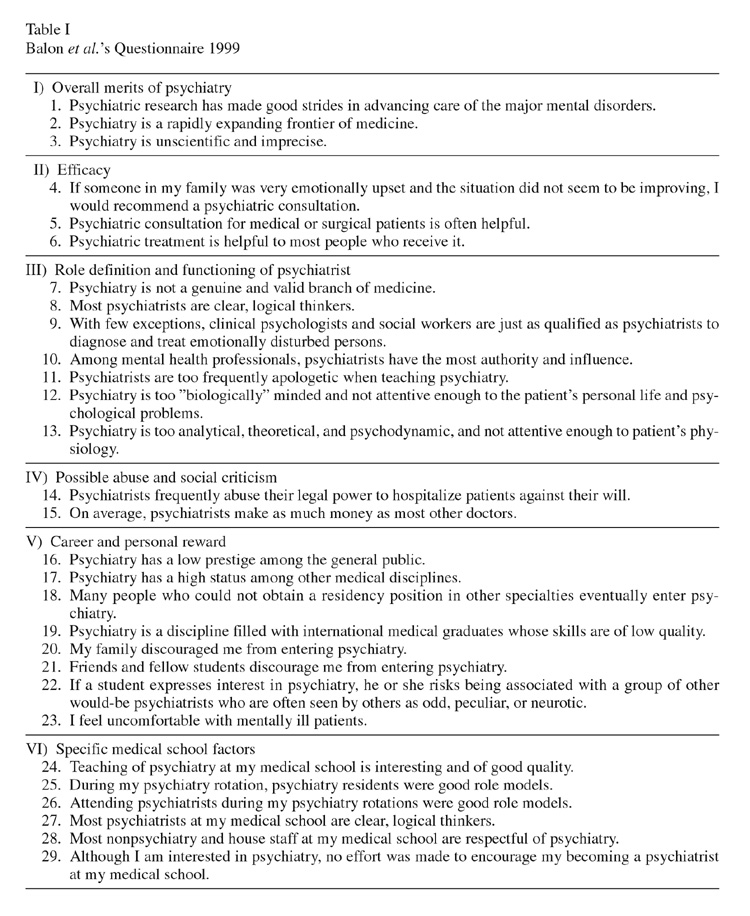

Balon et al.'s questionnaire (Table I) consisted of 39 questions, 29 of which examined the attitudes of medical students towards psychiatry and exploring six main areas: I) overall merits of psychiatry, II) efficacy, III) role definition and functioning of psychiatrists, IV) possible abuse and social criticism, V) career and personal reward and VI) specific medical school factors. Multiple-choice responses to each item were defined as follows: "strongly agree", "moderately agree", "moderately disagree" and "strongly disagree". A further four questions were included in order to record demographic characteristics such as sex, age, academic year and choice of medical specialties. A written explanation of the purpose of the study preceded the main questionnaire.

Students participating in the study were asked to complete the same questionnaire before and after completion of their psychiatry training in the 1999/2000 academic year. Students were given an oral guarantee that their responses to the questionnaire were absolutely anonymous and that neither academic, nor social risks, would be consequent upon their agreement to participate. In view of these conditions, returning an anonymous questionnaire was considered to be indicative of informed consent.

The statistical analysis was performed using a Macintosh Power PC 7600/120 and the program Statview 5.0. Due to the existence of missing data by a few subjects in a small number of questions, the descriptive analysis of the items concerning attitudes were converted into relative percentages, ignoring unanswered items. The data obtained before and after training in psychiatry were compared by means of the Wilcoxon test.

Results

Selected Demographic Characteristics

The index group consisted of 48 students. The gender distribution was 12 male (25%) and 36 female (75%). The mean age was 21.8 years (SD=0.97). All the students of the School who had done the psychiatry course answered both questionnaires. Therefore, there were no drop-outs.

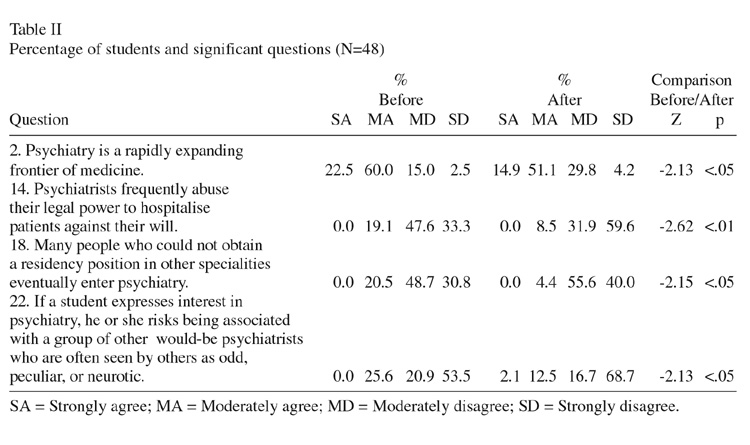

Attitudes and views about Psychiatry (Table II)

(I) Overall merits of psychiatry: There were few changes in the attitudes of the students in this aspect: students were less favorable to view psychiatry as a "rapidly expanding frontier of medicine" (from 82.5% to 66%) [Z= -2.13, p=.033].

(IV) Possible abuse and social criticism: The students' opinion concerning this aspect also changed. Students were less likely to agree that "psychiatrists abuse their legal power to hospitalize patients against their will", which reflects a more favorable attitude following training (from 80.9% to 91.5%) [Z=-2.62, p=.008].

(V) Career and personal reward: A more favorable attitude after doing psychiatry was also reflected in these questions. The students' opinions were less likely to agree with the statement that "most doctors who cannot obtain a residency position in other specialties eventually choose psychiatry" (from 20.5% to 4.4%) [Z=-2.15, p=.032]. Finally, students reported receiving greater support in their choice of psychiatry as a specialty after having completed training. They did not feel that an expression of interest in psychiatry is interpreted by others as an indication of them being regarded as "odd, peculiar or neurotic" (from 74.4% to 85.4%) [Z=-2.13, p=.033].

No significant changes before and after training were observed concerning areas of the questionnaire dealing with "(II) Efficacy", "(III) Role definition" and the "(VI) Specific medical school factors".

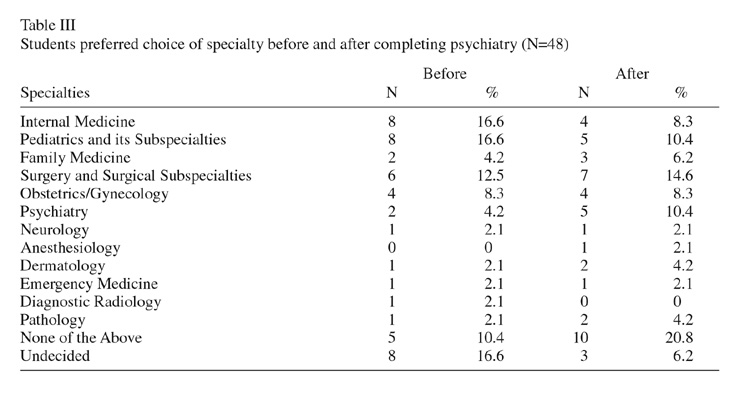

Professional future choice (Table III)

There was a decrease in the number of students choosing three medical specialties: Internal Medicine (16.6% vs. 8.3%), Pediatrics and Subspecialties (16.6% vs. 10.4%) and Diagnostic Radiology (2.1% vs. 0%). By contrast, the highest increases in the specialty choice were in Psychiatry (4.2% vs. 10.4%) and other less common specialties which appeared in the questionnaire as 'None of the Above' (10.4% vs. 20.8%). The decrease in the number of students undecided about their professional future at the end of the period of study was remarkable.

Discussion

The results of this paper show that a number of the attitudes expressed by our students in relation to psychiatry change in a more favorable direction after they have had some experience of the discipline. In particular, their view of psychiatrists in general improved and they were less likely to be influenced by negative social pressures when choosing psychiatry as their future career. This change means that the students get rid of previous negative attitudes and their knowledge of psychiatry increases. Therefore, as they know the field better (both theoretical and practical) they show a reduced bias (either positive and negative) and this co-occurs with an increase in the percentage of students selecting psychiatry as their preferred choice (from 4.2% to 10.4%).

A limitation of the paper is the small size of the sample, since the results were obtained just from one school. Our findings, then, might not necessarily generalize to the Spanish medical school population as a whole. Another limitation might have been associated with the translation of the questionnaire. However, we think that the back-translation validation cuts down the amount of errors due to changes of meaning. Furthermore, there may be some differences in Spanish and U.S. students' attitudes to some aspects of psychiatry that were not reflected in the translation. Despite these possible reservations, all the students in the school answered both questionnaires, and we believe that the preservation of anonymity in the study and the forced-choice nature of the questionnaire devised by Balon et al. 1999 allow a fair reflection of the students' perception of psychiatry to be elicited.

The number of students choosing psychiatry as a future career rose to 10.4% in our study after experience in psychiatry (the highest increase among the different specialties). In this sense, 16.6% of students were undecided respect their professional future at the beginning of the study. However, this figure was reduced to 6.2% at the completion of the study. This change is indicative of the decisions about the professional future that take place during the academic year. Apart from Psychiatry, other specialties which saw a choice increase were: Family Medicine, Surgery and Surgical Subspecialties, Anesthesiology, Dermatology, Pathology and other less common specialties not mentioned in the questionnaire. Therefore, it seems clear that students' intentions to pursue psychiatry as a career improved during the rotation, as McParland et al. 2003 stated. This percentage (10.4%) is considerably higher than the percentage nowadays in the U.S. (4.5%), which suggests that there is no reduction in vocations for psychiatry among our students.

The process for choosing a residency position in Spain differs from that of the U.S. since it is determined by an official exam and by the number of residency positions offered by the Ministry of Health. During the last decade the number of residency positions for psychiatry has increased by 33%. During the year 2002/2003, 2.9% of the total of 5496 residency positions offered in Spain by the Ministry of Health were in psychiatry, making it the eighth most frequently available specialty (Ministry of Health). This means that, despite the increase in the number of positions during the last decade, 72.1% of the students who expressed interest in psychiatry after their fourth year of medical school in our study were not able to enter psychiatry on completion of their studies.

As Brook pointed out in 1983 (Brook 1983), it is probable that a number of these students end up in family medicine positions, which is the specialty with most residency positions available (32.3% of a total of 5496 positions offered in 2002/2003). Therefore, the recruitment process is not a priority in the psychiatry training in Spain since the Ministry of Health yearly offers a number of positions for training programs according to the capacity of the accredited training centers, the national budget available and the social demand (Ministry of Health).

Some of the possible causes for this high percentage of Spanish students hoping to become psychiatrists could be the biopsychosocial model of illness encouraged throughout the first and sophomore years as Silverman et al. 1983 stated. Furthermore, Spanish students attend medical school at an earlier age than U.S. students, which makes these training schemes sooner available.

The percentage of students considering psychiatry as a future career follows a common pattern throughout the six years of medical school. The percentage is high during the first and sophomore years, then it declines after the first contact with a clinical internship (Eagle and Marcos 1980, Creed and Goldberg 1987), it rises after the psychiatry internship and finally gradually decreases until the completion of medical school. In the U.S. the psychiatry course generally consists of 4-7 weeks during the third year. It could help in order to increase the number of vocations towards psychiatry, to delay the psychiatry course until the final years of medical training.

Further studies are needed to analyze more precisely the relationships between currently held opinions and the percentage of students expressing interest in psychiatry alongside interactions with the students' contact with other specialties.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ana-Luisa Subirà Cuyàs for her invaluable help in translation tasks.

References

Alexander DA, Eagles JM. Changes in attitudes towards psychiatry among medical students: correlation of attitude shift with academic performance. Med Educ 1990; 24: 452-460. [ Links ]

Arkar H, Eker D. Influence of a 3-week psychiatric training programme on attitudes toward mental illness in medical students. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1997; 32: 171-176. [ Links ]

Balon R, Franchini GR, Freeman PS, Hassenfeld IN, Keshavan MS, Yoder E. Medical students attitudes and views of psychiatry. 15 years later. Acad Psychiatry 1999; 23: 30-36. [ Links ]

Baxter H, Singh SP, Standen P, Duggan C. The attitudes of 'tomorrow's doctors' towards mental illness and psychiatry: changes during the final undergraduate year. Med Educ 2001; 35: 381-383. [ Links ]

Brockington I, Mumford D. Recruitment into Psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 180: 307-312. [ Links ]

Brook P. Who's for psychiatry? Brit J Psychiat 1983; 142: 361-365. [ Links ]

Burra P, Kalin R, Leichner P, Waldron JJ, Handforth JR, Jarrett FJ, et al. The ATP 30 - a scale for measuring medical students' attitudes to psychiatry. Med Educ 1982; 16: 31-38. [ Links ]

Calvert SH, Sharpe M, Power M, Lawrie SM. Does undergraduate education have an effect on Edinburgh medical students' attitudes to psychiatry and psychiatric patients? J Nerv Ment Dis 1999; 187: 757-761. [ Links ]

Creed F, Goldberg D. Students' attitudes towards psychiatry. Med Educ 1987; 21: 227-234. [ Links ]

Crowder MK, Hollender MH. The medical students' choice of psychiatry as a career: a survey of one graduating class. Am J Psychiatry 1981; 138: 505-508. [ Links ]

Eagle PF, Marcos LR. Factors in medical students' choice of psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 1980;137: 423-427. [ Links ]

Eagle PF, Marcos LR. Impact of the outpatient clerkship on medical students. Am J Psychiat 1980; 137: 1599-1602. [ Links ]

Galletly CA, Schrader GD, Chesterman HM, Tsourtos G. Medical student attitudes to psychiatry: lack of effect of psychiatric hospital experience. Med Educ 1995; 29: 449-451. [ Links ]

Garyfallos G, Adamopoulou A, Lavrentiadis G, Giouzepas J, Parashos A, Dimitriou E. Medical students' attitudes toward psychiatry in Greece: An eight-year comparison. Acad Psychiatry 1998; 22: 92-97. [ Links ]

Koh KB. Medical students' attitudes toward psychiatry in a Korean medical college. Yonsei Med J 1990; 31: 60-64. [ Links ]

Lee EK, Kaltreider N, Crouch J. Pilot study of current factors influencing the choice of psychiatry as a specialty. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152: 1066-1069. [ Links ]

Malhi GS, Parker GB, Parker K, Carr VJ, Kirkby KC, Yellowlees P, et al. Attitudes toward psychiatry among students entering medical school. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2003; 107: 424-429. [ Links ]

McParland M, Noble LM, Livingstone G, McManus C. The effect of a psychiatric attachment on students' attitudes to and intention to pursue psychiatry as a career. Med Educ 2003; 37: 447-454. [ Links ]

Nielsen AC, Eaton JS. Medical students attitudes about psychiatry. Implications for psychiatric recruitment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38: 1144-1154. [ Links ]

Pailhez G, Bulbena A, Coll J, Ros S, Balon R. Attitudes and views on Psychiatry: A comparison between Spanish and U.S. medical students. Academic Psychiatry [ [ Links ]Accepted].

Pan P-C, Lee WH, Lieh-Mak FF. Psychiatry as compared to other career choices: a survey of medical students in Hong Kong. Med Educ 1990; 24: 251-25. [ Links ]

Reiser LW, Sledge WH, Edelson M. Four-year evaluation of a psychiatric clerkship: 1982-1986. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145: 1122-1126. [ Links ]

Samuel-Lajeunesse B, Ichou P. French medical students' opinion of psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142: 1462-1466. [ Links ]

Sierles FS, Taylor MA. Decline of U.S. medical student career choice of psychiatry and what to do about it. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152: 1416-1426. [ Links ]

Silverman D, Gartrell N, Aronson M, Steer M, Edbril S. In search of the biopsychosocial perspective: an experiment with beginning medical students. Am J Psychiat 1983; 140: 1154-1159. [ Links ]

Sivakumar K, Wilkinson G, Toone BK, Greer S. Attitudes to psychiatry in doctors at the end of their first post-graduate year: two-year follow-up of a cohort of medical students. Psychol Med 1986; 16: 457-460. [ Links ]

Soufi HE, Raoof AM. Attitude of medical students towards psychiatry. Med Educ 1992; 26: 38-41. [ Links ]

Wilkinson DG, Greer S, Toone BK. Medical students' attitudes to psychiatry. Psychol Med 1983; 13: 185-192. [ Links ]

Wilkinson DG, Toone BK, Greer S. Medical students' attitudes to psychiatry at the end of the clinical curriculum. Psychol Med 1983; 13: 655-658. [ Links ]

Yager J, Lamotte K, Nielsen AC, Eaton JS. Medical students' evaluation of psychiatry: A cross-country comparison. Am J Psychiatry 1982; 139: 1003-1009. [ Links ]

Yellowlees P, Vizard T, Eden J. Australian medical students' attitudes towards specialities and specialists. Med J Aust 1990; 152: 587-592. [ Links ]

Zimny GH, Sata LS. Influence of factors before and during medical school on choice of psychiatry as a specialty. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143: 77-80. [ Links ]

Address of correspondence:

Dr. Antonio Bulbena, M.D., MSc (Cantab)

Director of Institut Atenció Psiquiatrica.

Hospital del Mar. Barcelona.

Professor Titular Psychiatry. Universitat Autonoma Barcelona.

Paseo Marítimo 25-29. E- 08003 Barcelona. Spain

Tel 34-932483175

Fax 34-932483445.

E-mail: abulbena@acmcb.es

SPAIN