My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The European Journal of Psychiatry

Print version ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.24 n.2 Zaragoza Apr./Jun. 2010

Predictors of outcome in the early course of first-episode psychosis

Lizzette Gómez-de-Regil*; Thomas R. Kwapil**; Joan Manel Blanqué***; Elias Vainer***; Mónica Montoro***; Neus Barrantes-Vidal*,***,****

* Departament de Psicología Clínica i de la Salut, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Barcelona

** Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Greensboro. USA

*** Fundació Hospital Sant Pere Claver, Serveis de Salut Mental, Barcelona

**** CIBER Salud Mental, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Barcelona. SPAIN.

LGR wants to thank the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT), Mexico, for funding number 187498.

NBV and TRK are thankful to Generalitat de Catalunya for their support (2009SGR672).

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: The identification of characteristics that predict clinical and functional outcomes in patients with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders is essential for enhancing our understanding of the pathophysiology and the treatment of the disorder. The present study employed a retrospective design to examine the predictive validity of demographic, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics of first-episode patients on diagnosis, presence of residual psychotic symptoms, and number of psychotic episodes three to five years later.

Methods: Information on baseline predictor variables and outcome was obtained from the clinical records of 44 patients who had their first psychotic episode between 1999 and 2003 and whose available follow-up period was at least 3 years long (mean = 5.7 years, SD = 1.3 years).

Results: Male gender, single marital status, and poor premorbid adjustment were significantly associated with residual symptoms at follow-up. Poor insight at onset was significantly associated with subsequent relapses. Diagnosis of schizophrenia (as opposed to other psychotic disorders) at the follow-up assessment showed no significant association with any of the baseline predictors.

Conclusions: Consistent with previous findings, the constellation of male gender, single status, poor premorbid adjustment and poor insight appeared to predict especially poor outcome. Residual symptoms appear to be an especially useful index of clinical and functional status for examining the course and outcome of first-episode psychosis.

Key words: Schizophrenia; First-episode psychosis; Outcome predictors; Outcome criteria; Illness course.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is one of the most disabling mental disturbances; however, it can no longer be conceived as a hopeless and inevitable pathway to deterioration1. During the five years after the first psychotic episode (the so-called "critical period"), most patients are likely to relapse and/or present residual symptoms. Eventually, however, psychotic disorders appear to reach a plateau and follow a more stable course2,3. Nevertheless, some studies have documented great heterogeneity in illness course, such that between 12-22% of patients never relapse or present residual symptoms4. The identification of characteristics that predict clinical and functional outcomes in newly diagnosed psychotic patients should enhance our understanding of such disorders and provide guidance for treatment.

Research and intervention programs in early psychosis aim to reduce suicide and relapse rates, prevent social and cognitive deterioration and ameliorate persisting symptoms5,6. In this study area, outcome has been defined by a variety of clinical, functional and quality of life measures5. A widely used outcome criterion, and perhaps the most available, is diagnosis, which can be reliably established after approximately six months of onset7. Schizophrenic psychoses show, compared to schizoaffective and affective psychoses, a poorer global outcome, more deteriorating course, greater presence of negative symptoms, and more persistent impairments in several aspects of social life, such as communication and cognitive functions8,9. Illness course is also extensively reported as an outcome measure, varying from a full recovery to a chronic deteriorating course7,10-12. Some studies, simplifying the course of psychosis as "poor" or "good", have defined course by relying either on the presence of residual symptoms4,13 or on the occurrence of subsequent relapses14. However, there is a shortage of studies comparing the impact of using either one or the other, particularly on their ability to evaluate the utility of putative prognostic indicators.

Apart from outcome definitions, studies have also diverged in the analysis of premorbid and first-episode characteristics that might be predictive of outcome. Sociodemographic variables, clinical features, conditions of the premorbid phase, context of presentation of the first episode of psychosis, and type of treatment have been the most common factors related to early and long-term outcome. Literature on this topic is abundant, suggesting that among many factors, early age at onset, male gender, single status, poor premorbid adjustment, lack of insight, and symptom severity at onset, are highly related to poor outcome2,15, though not all findings concur5,6.

Research so far has identified important predictors of outcome. Nevertheless, and to the best of our knowledge, there is a shortage of studies analysing the association of premorbid and first episode variables with different outcome definitions. Therefore, this study aims at (i) replicating the prognostic value of factors previously related to the early course of psychosis in retrospectively assessed first-episode psychotic patients, and (ii) assessing their prognostic value according to three different outcome criteria (final diagnosis, presence of psychotic residual symptoms, and number of psychotic episodes).

Methods

Design and Case Selection

This is a retrospective case series study focusing on the early course of psychosis in a cohort of patients from an outpatient clinic in Barcelona, Spain. Data were collected through the review of clinical files after obtaining formal authorization and ethical approval from the Hospital Committee. Inclusion criteria were: (1) occurrence of a first episode of psychosis between 1999 and 2003; (2) age at onset between 18-45 years; and (3) a primary current DSM-IV-TR7 diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders (schizophreniform, schizoaffective, delusional, brief, or not otherwise specified). Exclusion criteria were: (1) psychoses of affective, organic, or toxic type, (2) an evident intellectual disorder, and (3) no follow-up information available. We identified 44 first-episode patients who met the criteria for inclusion in the study. These included 28 men and 16 women, with an average age at first episode of 27.6 years (SD = 7.6). All cases included had an available follow up of at least 3 years (mean = 5.7, SD = 1.3). Most patients (61.4%) had never interrupted their contact with the mental health service for any period of six months or longer. All patients had received antipsychotic medication.

Measures and Variables

Based upon findings in previous studies4,13,14, the predictors identified at the first episode included (1) sociodemographic data, (2) premorbid phase, (3) features of the context of the first episode, and (4) dimensions of psychotic psychopathology. For psychopathology clinicians rated the presence of symptoms corresponding to each of its three dimensions (psychoticism, disorganization, and negative symptoms) by translating the clinical records information into PANNS selected items16.

Outcome was classified according to three criteria. First, current diagnosis was established according to DSM-IV-TR7 criteria by experienced senior clinicians (EV, JMB, MM). After reaching clinical consensus, diagnoses were dichotomized into: 1) schizophrenia and, 2) other psychoses. A second criterion grouped cases as 1) with residual symptoms or, 2) with no residual symptoms at the time of the outcome assessment. A third criterion considered the number of psychotic episodes during the follow-up period (including the initial episode), classifying cases as 1) single episode or, 2) multiple episodes.

Results

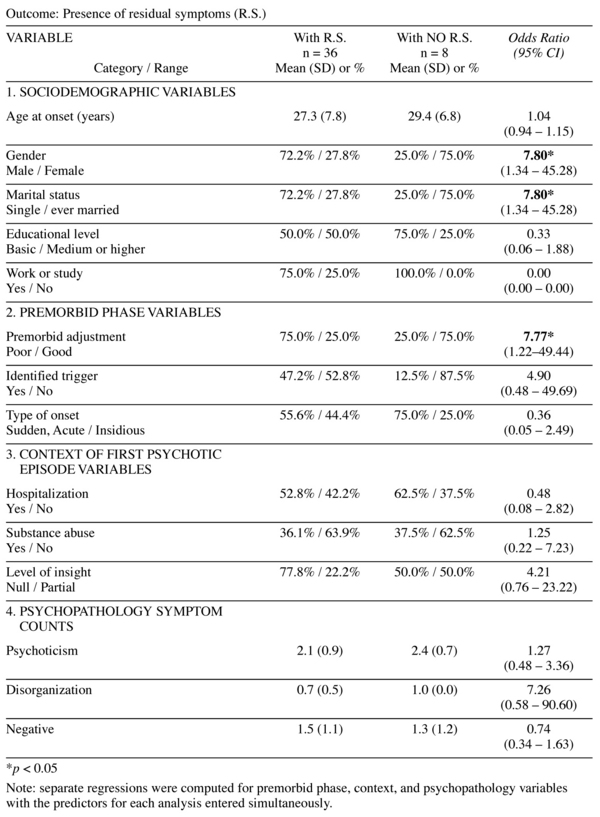

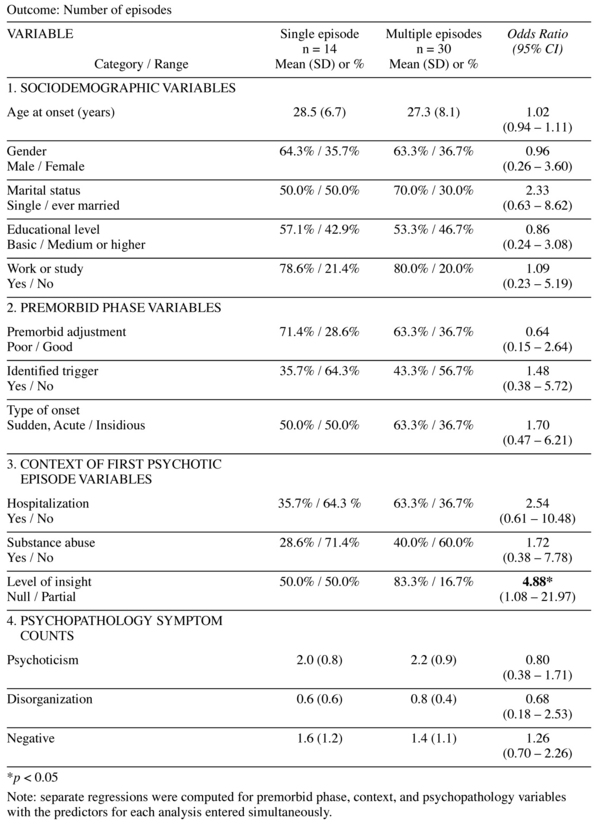

Table I presents a series of binary (sociodemographic variables) and multinomial (premorbid phase, context of the first episode, and psychopathology) logistic regressions computed to analyze the prediction of the three outcomes by the selected prognostic variables.

Patients who are male, who had never been married nor lived with a stable partner at the time of first admission, or had a poor premorbid adjustment, were significantly more likely to suffer from residual symptoms at the outcome assessment. Poor insight at first-episode predicted further relapses (multiple psychotic episodes).

Consideration was given to creating a composite outcome measure based upon the three outcome variables. However, the outcome variables did not correlate significantly with one another and an additive combination (reverse scoring of number of episodes) not surprisingly produced an unreliable variable (coefficient alpha = 0.35). Furthermore, it was not entirely clear what the nature of the composite variable was. As an alternative, a principal component analysis was conducted on the three outcome variables resulting in one interpretable component that accounted for 44% of the variance. This continuous variable was transformed to remove positive skew and correlated with the prognostic variables. However, only level of insight at the first episode correlated significantly with the outcome factor (with good insight associated with the non-psychotic/less residual/fewer episodes pole of the factor). Therefore, the possibility of constructing a composite outcome measure did not turn out to be informative and suggests the need of qualitatively taking into account a profile associated with the 3 outcome measures.

Discussion

This longitudinal retrospective study corroborates the significant association of male gender, single status, and poor premorbid adjustment with poor outcome as defined by the subsequent presence of residual symptoms. Also, poor insight was associated with the occurrence of multiple psychotic episodes. Dimensions of psychopathology were not associated to any of the three outcome definitions. Outcome defined by final diagnosis could not be predicted by any of the selected baseline factors.

Predictors of outcome

Both biological and psychosocial hypotheses have been put forward to explain gender differences in psychosis outcome (in this study indicated by males showing more residual symptomatology). Some authors have suggested that gender does not have a direct effect on symptomatology, but rather that it is related to underlying differences on social behaviour patterns. Men´s socially unfavourable illness behaviour (e.g., low acknowledgment of illness) would contribute to their poorer social course and overall outcome, whereas women´s higher tendency to prosocial behaviour, such as cooperativeness and compliance, would influence a more favourable outcome17. This pattern would be consistent with research showing that schizophrenic women have a better social functioning than schizophrenic men, regardless of age of onset and symptomatology18,19. In the biological domain, factors such as later brain maturation in males are hypothesised to render them more vulnerable to prenatal and perinatal neurodevelopmental insults, which may cause structural brain abnormalities that, in the case of schizophrenia, have been associated to chronic negative symptoms (i.e., residual status) and premature onset. Additionally, it has been suggested that estrogens may have a protective role for females by facilitating an earlier maturation of the brain and, thus, making them less vulnerable to neurodevelopmental impairment20. Thus, men would be more prone to a hypothesized poor-prognosis, neurodevelopmental subtype of schizophrenia, for which early environmental brain insults play an important etiologic role, whereas women would be more prone to a hypothesized good-prognosis, affective subtype, probably more genetically related to affective disorders21.

Individuals who were single at onset also showed poorer outcome (residual symptomatology). Although results are not reported, statistical tests showed us that this association was not due to age at onset, gender, premorbid adjustment, or continued contact with the mental health service. Marital status (ever married or lived with a stable partner) has been shown to have an independent onset-delaying effect, even more marked in males, which suggests that it is not earlier age of onset (related to male gender) what prevents individuals from getting married, but rather that being married is what delays onset, and it could as well prevent the emergence and chronicity of residual symptomatology22.

Poor premorbid adjustment was significantly associated to residual symptomatology. This association seems to be developmentally meaningful, as residual symptoms could be understood as the continuation of the dysfunction already present before the psychotic exacerbation. Poor premorbid adjustment has been associated with more negative symptoms in the early course of illness, less improvement in negative symptoms, and overall poorer clinical and social functioning23; whereas good premorbid adjustment has been related to better clinical outcome, not only in chronic schizophrenia, but also in affective psychoses (i.e. bipolar disorder, major depression with psychosis)23 and in psychotic disorders that are substance induced24.

Poor insight was also associated to poor outcome, but this time defined by occurrence of multiple psychotic episodes, not by residual symptoms. This result is consistent with previous reports indicating that individuals experiencing a first episode of psychosis who have little insight are at increased risk of discontinuing their medication25, disengaging from treatment26, and thus increasing the chances of relapse. In this study, though, insight and continued contact with the mental health service showed no significant association.

In this study, opposite to what was expected, none of the three dimensions of psychopathology was associated with outcome. Outcome in psychosis might well be predicted by baseline psychopathology, particularly by negative symptomatology27. Negative symptoms (e.g. social withdrawal and anhedonia), rather than the characteristic positive and even disorganization symptoms, seem one of the strongest factors discriminating people who later develop schizophrenia 28,29. Moreover, the association of negative symptoms at onset with later residual symptomatology appears significant and even stronger than their association with other dimensions of psychosis (e.g. psychoticism and disorganization) or dimensions of premorbid personality 30. It might be that in the current study clinicians mostly focused on the recording of the more striking positive and disorganized symptoms, either because of an assessment bias or because negative symptoms at the time of first episode tend to be masked by those symptoms that cause severe behavioural disturbances.

Analysis of three outcome criteria

The three outcome criteria showed no significant associations among them, suggesting the relevance of using each of them to map with completeness the course and outcome of first-episode psychosis. None of the selected sociodemographic, premorbid, first-episode or psychopathology variables could significantly distinguish between patients who developed schizophrenia from those who had a different kind of psychosis. Although the result could be due to insufficient statistical power, an alternative possibility is that none of these predictors is specifically associated with schizophrenic or non-schizophrenic psychoses, which would be consistent with research supporting that despite schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and affective illness are prototypical entities, they share common features and a general set of aetiological and risk factors31,32.

Presence of residual symptoms was the most distinguishable outcome from baseline indicators. Over time, the treatment of schizophrenia and related psychoses has evolved, making the improvement of psychosocial functioning and quality of life feasible aims, in addition to the amelioration of positive symptoms33,34. However, episode remission is not enough for recovery because persistent symptomatology, even if at a low level of severity, can interfere with behaviour and functioning, hindering patients´ chances of social reintegration35. Thus, the possibility of identifying at first-episode patients likely to suffer residual symptomatology has significant implications for treatment and service planning.

The number of relapses could only be associated with baseline level of insight. Relapses have an important effect not only on the clinical, but also on the social functioning of patients36. Exacerbation of symptoms and hospitalizations might cause cumulative deterioration in functioning and a diminished ability to maintain employment and relationships35. Thus, early intervention treatment programs in psychosis work hardly to prevent relapses and to promote the maintenance of a stable clinical status34. Abundant research, replicated as well in the present study, highlights the important role of insight at illness onset as a prognostic factor37.

In summary, schizophrenia and other related psychoses cannot longer be seen as a definite conviction to deterioration, as the course of the disorder has shown to be heterogeneous. Here, three alternative definitions of outcome were analysed: final diagnosis, presence of residual symptoms, and number of psychotic episodes. Findings indicate that being male, single marital status at onset, poor premorbid adjustment, and lack of insight are significant predictors of "poor" outcome in the early course of first-episode psychotic patients. Furthermore, these factors better distinguish patients´ outcome when this is defined as presence of residual symptomatology. Thus, residual symptomatology stands out as an important measure of the outcome / course of the disorder and attention must be placed to its standardized assessment and follow-up.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank all clinicians from Fundació Hospital Sant Pere Claver for their collaboration and making this research possible.

References

1. Penn DL, Waldheter EJ, Perkins DO, Mueser KT, Lieberman JA. Psychosocial treatment for first-episode psychosis: A research update. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162(12): 2220-2232. [ Links ]

2. Barnes TRE, Pant A. Long-term course and outcome of schizophrenia. Psychiatry 2005; 4(10): 29-32. [ Links ]

3. McGorry PD. "A stitch in time" ... the scope for preventive strategies in early psychosis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 248(1): 22-31. [ Links ]

4. Rosen K, Garety P. Predicting recovery from schizophrenia: A retrospective comparison of characteristics at onset of people with singe and multiple episodes. Schizophr Bull 2005; 31(3): 735-750. [ Links ]

5. Malla AK, Norman RMG, Joober R. First-episode psychosis, early intervention, and outcome: What have we learned? Can J Psychiatry 2005; 50(14): 881-891. [ Links ]

6. Menezes NM, Arenovich T, Zipursky RB. A systematic review of longitudinal outcome studies of first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med 2006; 36(10): 1349-1362. [ Links ]

7. American Psychiatric Association, editor. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [ Links ]

8. Marneros A, Deister A, Rohde A. Psychopathological and social status of patients with affective, schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorders after long-term course. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1990; 82(5): 352-358. [ Links ]

9. Möller H, Bottlender R, Wegner U, Wittmann J, Strauß A. Long-term course of schizophrenic, affective and schizoaffective psychosis: Focus on negative symptoms and their impact on global indicators of outcome. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 102: 54-57. [ Links ]

10. Ciompi L. The natural history of schizophrenia in the long term. Br J Psychiatry 1980; 136: 413-420. [ Links ]

11. Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G, Anker M. Schizophrenia: Manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures: A world health organization ten-country study. Psychol Med 1992; 20: 1-97. [ Links ]

12. Shepherd M, Watt D, Falloon I, Smeeton N. The natural history of schizophrenia: A five-year follow-up study of outcome and prediction in a representative sample of schizophrenics. Psychol Med 1989; 15: 1-46. [ Links ]

13. Vázquez-Barquero JL, Cuesta MJ, Castanedo SH, Lastra I, Herrán A, Dunn G. Cantabria first-episode schizophrenia study: Three-year follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174: 141-149. [ Links ]

14. Altamura AC, Bassetti R, Sassella F, Salvadori D, Mundo E. Duration of untreated psychosis as a predictor of outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: A retrospective study. Schizophr Res 2001; 52(1): 29-36. [ Links ]

15. Tandon R, Keshavan MS, Nasrallah HA. Schizophrenia, "just the facts": What we know in 2008: Part 1: Overview. Schizophr Res 2008; 100(1): 4-19. [ Links ]

16. Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT, Kane JM, Lasser RA, Marder SR, Weinberger DR. Remission in Schizophrenia: Proposed Criteria and Rationale for Consensus. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 441-449. [ Links ]

17. Häfner H. Gender differences in schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003; 28: 17-54. [ Links ]

18. Ochoa S, Usall J, Villalta-Gil V, Vilaplana M, Márquez M, Valdelomar M, et al. Influence of age at onset on social functioning in outpatients with schizophrenia. Eur J Psychiat 2006; 20(3): 157-163. [ Links ]

19. Usall J, Haro JM, Araya S, Moreno B, Muñoz PE, Martínez A, et al. Social functioning in schizophrenia: what is the influence of gender? Eur J Psychiat 2007; 21(3): 199-205. [ Links ]

20. Usall J. Diferencias de género en la esquizofrenia. Rev Psiquiatría Fac Med Barna 2003; 30(5): 276-287. [ Links ]

21. Salem JE, Kring AM. The role of gender differences in the reduction of etiologic heterogeneity in schizophrenia. Clin Psychol Rev 1998; 18(7): 795-819. [ Links ]

22. Jablensky A, Cole SW. Is the earlier age at onset of schizophrenia in males a confounded finding? Results from a cross-cultural investigation. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170(3): 234-240. [ Links ]

23. Haim R, Rabinowitz J, Bromet E. The relationship of premorbid functioning to illness course in schizophrenia and psychotic mood disorders during two years following first hospitalization. J Nerv Ment Dis 2006; 194(10): 791-795. [ Links ]

24. Caton CLM, Hasin DS, Shrout PE, Drake RE, Domínguez B, Samet S, et al. Predictors of psychosis remission in psychotic disorders that co-occur with substance use. Schizophr Bull 2006; 32(4): 618-625. [ Links ]

25. McEvoy JP, Johnson J, Perkins D, Lieberman JA, Hamer RM, Keefe RSE, et al. Insight in first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med 2006; 36(10): 1385-1393. [ Links ]

26. Buckley PF, Wirshing DA, Bhushan P, Pierre JM, Resnick SA, Wirshing WC. Lack of insight in schizophrenia: Impact on treatment adherence. CNS Drugs 2007; 21(2): 129-141. [ Links ]

27. Murray RM, Sham P, Van Os J, Zanelli J, Cannon M, McDonald C. A developmental model for similarities and dissimilarities between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res 2004; 71(2): 405-416. [ Links ]

28. Kwapil TR. Social anhedonia as predictor of the development of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 1998; 107(4): 558-565. [ Links ]

29. Johnstone EC, Ebmeier KP, Miller P, Owens DGC, Lawrie, SM. Predicting schizophrenia: findings from the Edinburgh High-Risk Study. Br J Psychiatry 2005; 186: 18-25. [ Links ]

30. Cuesta MJ, Peralta V, Gil P, Artamendi M. Premorbid negative symptoms in first-episode psychosis. Eur J Psychiat 2007; 21(3): 220-229. [ Links ]

31. Murray RM, Sham P, Van Os J, Zanelli J, Cannon M, McDonald C. A developmental model for similarities and dissimilarities between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res 2004; 71(2): 405-416. [ Links ]

32. Tsuang MT, Stone WS, Faraone SV. Toward reformulating the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157(7): 1041-1050. [ Links ]

33. Kane J. Progress defined-short-term efficacy, long-term effectiveness. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2001; 16: s1-s8. [ Links ]

34. Taylor M, Chaudhry I, Cross M, McDonald E, Miller P, Pilowsky L, et al. Towards consensus in the long-term management of relapse prevention in schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp 2005; 20(3): 175-181. [ Links ]

35. Nasrallah HA, Lasser R. Improving patient outcomes in schizophrenia: Achieving remission. J Psycho-pharmacol 2006; 20(6): 57-61. [ Links ]

36. Di Marzo S, Giordano A, Pacchiarotti I, Colom F, Sánchez-Moreno J, Vieta E. The impact of the number of episodes on the outcome of Bipolar Disorder. Eur J Psychiat 2006; 20(1): 21-28. [ Links ]

37. Lincoln TM, Lüllmann E, Rief W. Correlates and long-term consequences of poor insight in patients with schizophrenia. A systematic review. Schizophr Bull 2007; 33(6): 1324-1342. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Neus Barrantes-Vidal

Departament de Psicologia Clínica i de la Salut

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Bellaterra (Barcelona), Spain, 08193

Tel. +34 93 581 3864

Fax. +34 93 581 2125

E-mail: Neus.Barrantes@uab.cat

Received: 11 March 2009

Revised: 7 December 2009

Accepted: 18 December 2009