My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The European Journal of Psychiatry

Print version ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.25 n.2 Zaragoza Apr./Jun. 2011

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0213-61632011000200005

Predictors of negative attitudes toward mental health services: A general population study in Japan

Niwako Yamawaki; Craig Pulsipher; Jamie D. Moses; Kyler R. Rasmuse; Kyle A. Ringger

Department of Psychology, Brigham Young University. USA

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: As the impact of psychiatric disorders increases in Japan, finding a method of predicting attitudes towards mental health services has become increasingly important.

Aims: This study examined the factors that influence negative attitude toward mental health services among a general population in Japan.

Methods: Data from a survey asking 2,023 Japanese adults about desire to receive counseling, perceived level of knowledge about counseling, desire to live in the same neighborhood in the future, choice of persons to talk to about psychiatric problems, and demographic information were analyzed.

Results: Women reported greater desire to receive psychiatric treatment than men did and were more often willing to consult with friends and family about mental health issues. Older individuals showed more negative attitudes than those in younger age groups. Those who anticipated staying in the same neighborhood also reported being less likely to have desire to seek treatment.

Conclusions: Fear of stigma is one of the explanations of the negative attitudes toward psychiatric treatment. Given that age, gender, and perceived knowledge of treatment predicted the negative attitudes toward seeking mental health services, community intervention programs should be developed to target such populations, educate individuals, and ameliorate stigma about such treatment.

Key words: Help-seeking attitudes; Psychiatric disorders; Japan; Community survey.

Introduction

Every three years in October, the Japanese Ministry of Heath, Labor and Welfare conducts a research study to determine the number of individuals who have sought the help of mental health services for psychiatric disorders. According to the most recent report, the total number of individuals who utilized mental health services in 2005 was approximately 2,647,000. Among them, one-third sought help for mood disorders, which have one of the highest occurrence rates among psychiatric disorders in Japan, and which experienced the highest net increase when compared to other psychiatric disorders: Approximately 924,000 individuals reported seeking help for mood disorders in 2005, which more than doubled since 1996 (433,000)1.

Individuals with psychiatric disorders often suffer greatly-and the impact of these disorders ripples beyond the affected individuals. For instance, in the U.S., researchers found that employees with mood disorders lowered the morale of their coworkers, resulting in higher turnover of staff and general discontent2. The studies of the burden of mental disorders have been largely limited to Europe, North America, and Australia. However, similar social costs of mental disorders have also been examined in Japan. For example, the percentage (0.5%) of those with mental disorders who hold regular jobs is far lower than the percentage of people with physical disability (11.4%) and mental retardation (24.8%) who are regularly employed. Thus, people with psychiatric disability face significant barriers when trying to find work in Japan3.

Two solutions for such pervasive problems are psychotherapy and psychopharmacological treatments, which have been repeatedly found effective4-6. However, notwithstanding the benefits of psychiatric treatment, Asian countries in general tend to underutilize treatment for psychiatric disorders7. For instance, a 2004 study conducted by the World Health Organization revealed that Japan has the highest suicide rates among the developed countries of the world, yet of those who complete suicide, three-fourths did not receive psychiatric treatment in the year before the suicide8. Although the mental health care system in Japan has improved over the past decade8, individuals who need mental health services the most still seem to underutilize such services9. Today, psychiatric disorders are widespread in Japan and contribute substantially to the total burden of disease, making the stipulation of adequate and early care for people with mental disorders one of the most pressing public health issues9.

Previous research indicates a variety of reasons that people are reluctant to seek help from mental health professionals. Severity of symptoms, lack of knowledge of the effectiveness of therapy on psychiatric disorders, and fear of social stigma, for instance, are all significant barriers leading to underutilization of mental health services10,11. Another factor is one's attitude toward such services, and toward help-seeking in general, with attitude being conceptualized as a function of specific beliefs regarding the consequences of a behavior and an evaluation of those consequences12. Indeed, previous research has found that participants' decisions to seek help were associated with their attitude toward mental health services13. Further, Leaf et al. similarly reported that the attitudes one holds toward psychiatric services are associated with both the likelihood of seeking help and the quantity of such services used14. Therefore, investigating factors that influence such attitudes is critical.

Although the prevalence of mental disorders in Japan is widespread in all ages, one of the shortcomings of previous attitude studies is that a majority were conducted using only college students15-18. Therefore, the present study examined attitude toward psychiatric services using a large sample from the general population in Japan. In particular, this study used the Japan General Social Survey (JGSS) to explore factors that influence Japanese people's attitude toward receiving psychiatric treatment and to learn how they deal with psychiatric problems. In the present study, the following roles were examined in their effect on Japanese attitudes toward psychiatric services: knowledge of counseling, desire to remain in the same neighborhood, demographic factors, and choice of confidant to talk with about psychiatric problems.

Knowledge of Counseling

Previous studies revealed that people's knowledge of counseling services has been positively associated with better attitudes toward mental health services19,20. Although these studies were conducted using college students, it is still reasonable to hypothesize that knowledge of counseling would predict a person's desire to receive counseling in the Japanese general population.

Desire to Remain in the Same Neighborhood

According to Corrigan, the most cited reason why people decided not to seek psychiatric services is because of the stigma associated with seeking these services21. Individuals who seek psychiatric services are viewed as less socially acceptable and less favorable, and receive more negative treatment from others22,23. Indeed, Yamawaki found that fear of stigmatization for receiving counseling significantly influences willingness to seek psychiatric services24. People who desire to maintain their place of residence may worry about stigmatization more than people who anticipate changing neighborhoods. Therefore, respondents who want to live in the same neighborhood would probably show less desire to receive counseling than individuals who do not.

Demographic Factors

Bulk of literature suggest that women ha-ve consistently shown more favorable attitudes toward psychiatric help-seeking than men25-27. Thus, we expect that a similar pattern would probably also be found in the general population of Japan. On the contrary, in regards to the effect of age on seeking psychiatric services, it is far from consistent. For instance, some findings demonstrated that older individuals tend to view psychiatric help more negatively than younger individuals28, while some findings showed no effect of age29. Still, other findings indicated that older adults tended to held more positive attitudes than young adults30. One of the aims of this study is to explore the effect of age on psychiatric help-seeking attitudes using a representative sample in Japan.

Preference of Confidant to Talk with about Psychiatric Problems

Attitudes toward various types of formal/informal help are also crucial to explore. Jorm et al. conducted a cross-cultural comparison of the Japanese and Australian lay people's perception of how a person with a psychiatric disorder best be helped31. The results showed that Japanese participants were less likely to discuss psychiatric disorders with others beside their family members than Australian participants. The present study will investigate Japanese lay people's preference of confidant to talk with in case of a "nervous breakdown" or "great personal worry." In particular, this study examined the participants' preference for informal (family or friends/significant others) or formal (mental health professionals) confidants. It is expected that Japanese individuals prefer informal confidants when discussing psychiatric problems.

Method

Participants

The present examination was conducted using data from the 2005 JGSS. The database was obtained via the inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. The sample was identified through a multistage random sampling procedure that targeted adults living in households throughout Japan32. The purpose of the JGSS was to solicit political, sociological, and economic information from people living in Japan. In addition to the demographic, employment, and quality of life questions, this survey also addressed physical and mental health conditions of respondents as well as their attitude toward mental health services. Furthermore, respondents were asked about their willingness to talk about mental health issues with family members, friends or significant others, and mental health professionals, such as psychiatrists, counselors, and general doctors.

A total of 2,023 Japanese adults completed this survey between August and November 2005. Among them, 920 (45.5%) were men and 1,103 (54.5%) were women. Their ages ranged from 20 to 89 with a mean age of 52.95 (s.d. = 16.91). Approximately 72% of the participants were currently married, 4% were divorced, 8% were widowed, and 15% were never married. In the present study, 86 individuals who reported that they have undergone psychological counseling were excluded (4%).

Measures

Attitude toward receiving counseling

To examine the respondents' attitude toward receiving counseling, individuals who had not received any counseling in the past five years were asked whether they have had any desire to receive counseling from psychiatrists or counselors. Participants rated this item on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Agree) to 4 (Strongly Disagree).

Perceived knowledge about counseling

All participants were asked to rate their perceived level of knowledge about counseling or psychology. Participants rated this item ("Do you think that you have more knowledge of counseling or psychology than the average person?") on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (Certain Degree) to 4 (Not at all).

Desire to remain in the same neighborhood

Participants were asked to rate an item about whether they want to live in the same neighborhood in the future. Participants rated this item on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Agree) to 4 (Strongly Disagree).

Choice of confidant to talk with about psychiatric problems

Respondents were asked to complete an item asking, "With drastic changes in society, the issue of mental health has become important. If you were suffering from great personal worry or stress and were concerned you might have a nervous breakdown, with whom do you think you might like to talk? Choose all that apply." There were several choices in the original survey: (a) family, (b) friends, acquaintances, or significant others, (c) psychiatrist or psychosomatic physicians, (d) other doctors, (e) clinical psychologists, counselors, or other specialists in psychology, (f) persons of religion such as monks or priests, and (g) others (please specify). For the present study, "persons of religion" and "others" were not included in the analysis because less than 1% of participants wished to consult with them (1% and 0.6%, respectively). Additionally, items (c), (d), and (e) were combined into a new category, called "mental health service providers." Participants who answered any one of (c), (d), or (e) were rated as choosing to talk to mental health service providers.

Results

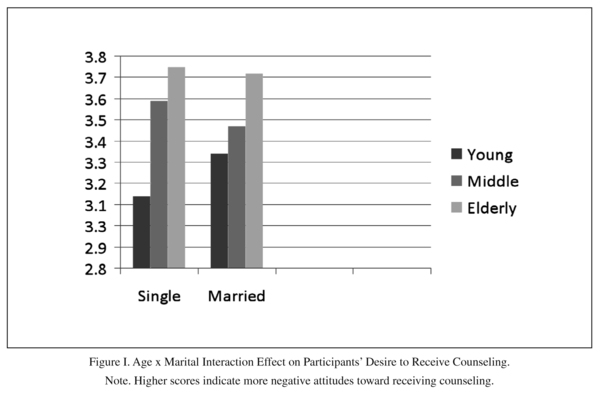

To examine the effect of gender, age, and marital status differences on participants' attitude toward receiving counseling, we first divided the participants by age into young (20-40 years old), middle aged (41-60), and elderly (61 and above). Having trichotomized the participants in this fashion, we then subjected scores for attitude toward receiving counseling to a 2 (male vs. female) x 2 (single vs. married) x 3 (age: young, middle, and elderly) ANOVA. Main effects of gender [F (2, 1,720) = 17.30, p < 0.0001], age [F (2, 1,720) = 54.90, p < 0.0001], and an interaction effect of Age x Marital Status [F(2, 1,720) = 7.75, p < 0.0001] were found. For the main effect of age, Tukey's post hoc analysis showed that all age ranges significantly differed from each other in regard to their attitude toward receiving counseling (means: young = 3.25, middle = 3.49, and elderly = 3.73; p < 0.0001). That is, the older the participants, the more negative their attitude toward receiving counseling. As for the effect of gender, men showed more negative attitude toward receiving counseling than did women. In regard to the Age x Marital Status interaction effect, young single participants tended to hold a more negative attitude toward receiving counseling than young married participants. Conversely, single middle-aged participants showed a more positive attitude than married middle-aged participants. Figure I represents the mean differences for the Age x Marital Status interaction effect.

To investigate the predictive effects of age, gender, knowledge of counseling, and desire to remain in the same neighborhood in the future, a multiple regression analysis was conducted on attitude toward receiving counseling. The results showed that age (β = 0.247, p < 0.0001), desire to remain in the same neighborhood (β = -0.147, p < 0.0001), perceived knowledge of counseling (β = 0.123, p < 0 .0001), and gender (β = -0.098, p < 0.0001, coding for male = 1, female = 2) were all significantly regressed on attitude toward receiving mental health services.

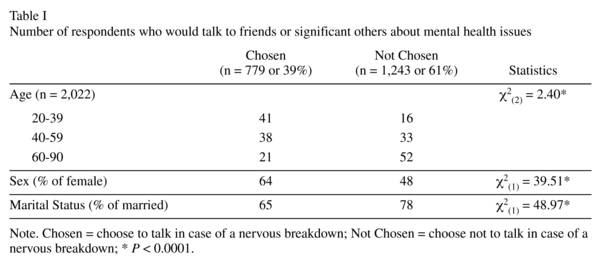

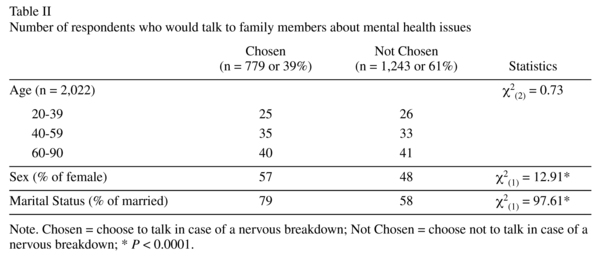

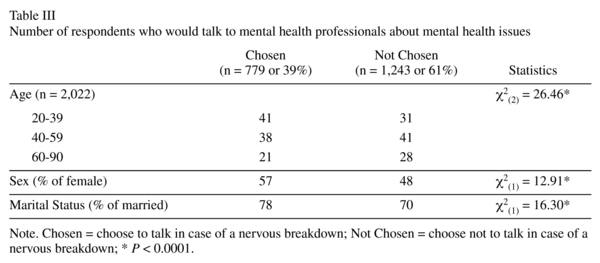

Chi-square analyses were performed to examine the effects of gender, age, and marital status on participants' choice of with whom they would talk in case of a mental health crisis. The individuals who chose to consult with their friends or significant others were more likely than individuals who chose otherwise to be young, female, and single (Table I). The participants who chose to consult with their family members were more likely than participants who chose otherwise to be female and married (Table II); no effect of age was found through this analysis. Table III represents the effects of age, gender, and marital status on the choice to talk to mental health professionals. The respondents who said they would choose to consult with mental health professionals were more likely than individuals who chose otherwise to be young, female, and married.

Discussion

The present study revealed some patterns of Japanese individuals' attitude and tendency to deal with psychiatric problems. Given that the majority of previous studies investigating attitudes toward psychiatric services were conducted using small samples of college students, this study is particularly helpful for its use of a large sample of individuals more representative of the general Japanese population.

Consistent with studies conducted in Western societies25,27,33-35, the present study revolved that female participants hold positive attitudes toward receiving counseling and tend to talk to their friends, families, and mental health professionals more than male participants do. This tendency may be explained by the framework of the theory of gender socialization. In both the west and in Japan, men are generally expected to be self-reliant, stoic, emotionally in control, competitive, independent, and successful, while women are generally expected to be dependent, emotionally expressive, affectionate, and passive25. Such socialization may encourage Japanese women to seek mental health services and may discourage Japanese men from doing the same.

Age was a consistent factor influencing participants' attitudes toward receiving coun-seling from psychiatrists or counselors. That is, the younger the participants, the more positive their attitudes were toward receiving counseling from mental health professionals. This finding is contradictory to the findings in Western societies that, in general, older adults tended to show more positive attitudes toward psychiatric services than younger adults. This pattern is particularly problematic for older Japanese individuals since the older people become, the more likely they are to suffer from mood disorders36. The age trend might be explained by suggestions from Currin, Hayslip, and Kooken that older adults tend to have less knowledge of the range and the causes of mental disorders, which correlates with negative attitudes toward psychiatric services37. Further, as Lebowitz and Niederehe suggested, stigma of mental illness is especially strong in older adults38. Due to the high rates of mental health problems often found in older populations, it is crucial to educate older adults29,39, particularly addressing their fear of stigmatization for seeking mental health services.

As we expected, participants' gender, age, desire to remain in the same neighborhood, and perceived knowledge about counseling were all predictors of their desire to receive mental health services. Interestingly, more than gender or perceived knowledge of counseling, desire to remain in the same neighborhood was the greatest predictor. Because fear of stigma is particularly strong in Japanese society24,40, it is probable that individuals who feel respected in their neighborhoods and desire to remain there will be particularly hesitant to risk stigmatization. The data supported our hypotheses in these areas.

As expected, age, marital status, and gender were significant factors that influenced with whom participants would wish to talk in case of a mental health crisis, such as a nervous breakdown. Young, single females tend to talk to their friends or significant others, while married females tend to talk to their family members. These findings indicate that older men might be particularly at risk for underutilization of mental health services. Community intervention programs targeting such populations should be developed.

The results of this study may be particularly helpful for Japanese mental health service providers as well as for those who provide services for recent immigrants from Japan. Our results showed that one of the significant predictors for negative attitudes toward psychiatric services was the participants' desire to live in the same neighborhood. This may well likely be because of their fear of others to know that they receive psychiatric services. Therefore, it is crucial for mental health providers to emphasize that the service they receive is completely confidential. Confidentiality should be thoroughly discussed with and understood by Japanese clients, particularly older men. Furthermore, Sirey, et al. found that perceived stigma, which is individuals' belief that others will devalue or discriminate against them due to their utilization of mental health services, predicted early treatment discontinuation among elderly patients with major depression41. Thus, individuals' fear of being known by others for receiving psychiatric help should be frequently discussed during treatment.

Some limitations of the present study should be noted. Since the data of this study were taken from the Japanese General Social Survey, all variables were measured by single items. Therefore, caution must be exercised in drawing causal inferences, and the findings are only suggestive and invite further investigation. Using a more sensitive standardized survey for attitude toward mental health services would improve future studies in this area. It is hoped that information about the attitudes of those least likely to seek help for psychiatric disorders will aid policymakers, educators, and community health workers in reaching the populations who need these services most.

References

1. Family doctors enlisted in war on depression. The Japan Times Online [Internet]. 2007 Aug 22 (cited 2009 May 15); Kyodo News:[about 1 screen]. Available from: http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20070822a5.html [ Links ]

2. Langlieb AM, Kahn JP. How much does quality mental health care profit employers? J Occup Environ Med 2005; 47(11):1099-1109. [ Links ]

3. Ozawa A, Yaeda J. Employer attitudes toward employing persons with psychiatric disability in Japan. J Vocat Rehabil 2007; 26(2): 105-113. [ Links ]

4. Golden RN, Gaynes BN, Ekstrom RD, Hamer RM, Jacobsen FM, Suppes T, et al. The efficacy of light therapy in the treatment of mood disorders: A review and meta-analysis of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162(4): 656-662. [ Links ]

5. Smith LA, Cornelius V, Warnock A, Bell A, Young AH. Effectiveness of mood stabilizers and antipsychotics in the maintenance phase of bipolar disorder: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Bipolar Disord 2007; 9(4): 394-412. [ Links ]

6. Williams J, Hadjistavropoulos T, Sharpe D. A meta-analysis of psychological and pharmacological treatments for body dysmorphic disorder. Behav Res Ther 2006; 44(1): 99-111. [ Links ]

7. WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the world health organization world mental health surveys. JAMA 2004; 291(21): 2581-2590. [ Links ]

8. Abe R, Shioiri T, Someya T. Suicide in Japan. Psychiatr Serv 2007; 58(7). [ Links ]

9. Naganuma Y, Tachimori H, Kawakami N, Takeshima T, Ono Y, Uda H, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in four areas in Japan: Findings from the world mental health Japan survey 2002-2003. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006; 60(2): 240-248. [ Links ]

10. Meltzer H, Bebbington P, Brugha T, Farrell M, Jenkins R, Lewis G. The reluctance to seek treatment for neurotic disorders. Int Rev of Psychiatry 2003; 15(1-2): 123-128. [ Links ]

11. Thompson A, Hunt C, Issakidis C. Why wait? Reasons for delay and prompts to seek help for mental health problems in an Australian clinical sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2004; 39(10): 810-817. [ Links ]

12. Halgin RP, Weaver DD, Edell WS, Spencer PG. Relation of depression and help-seeking history to attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. J Couns Psychol 1987; 34(2): 177-185. [ Links ]

13. Greenley JR, Mechanic D. Social selection in seeking help for psychological problems. J Health Soc Behav 1976; 17(3): 249-262. [ Links ]

14. Leaf PJ, Livingston MM, Tischler GL, Weissman MM, Holzer CE, Myers JK. Contact with health professionals for treatment of mental or emotional problems. Med Care 1985; 23(12): 1322-1337. [ Links ]

15. Tomoda A, Mori K, Kimura M, Takahashi T, Kitamura T. One-year prevalence and incidence of depression among first-year university students in Japan: A preliminary study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000; 54(5): 583-588. [ Links ]

16. Iga M. Suicide of Japanese youth. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1981; 11(1): 17-30. [ Links ]

17. Pfeffer CR. Suicide in Japan. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991; 30(5): 847-848. [ Links ]

18. Toyama M, Sakurai S. Self-perception and mental health. Jpn J Educ Psychol 2000; 48(4): 454-461. [ Links ]

19. Goh M, Xie B, Wahl KH, Zhong G, Lian F, Romano JL. Chinese students' attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. Int J Adv Couns 2007; 29(3-4): 187-202. [ Links ]

20. Gonzalez JM, Tinsley HEA, Kreuder KR. Effects of psychoeducational interventions on opinions of mental illness, attitudes toward help seeking, and expectations about psychotherapy in college students. J Coll Student Development 2002; 43(1): 51-63. [ Links ]

21. Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol 2004; 59(7): 614-625. [ Links ]

22. Sibicky M, Dovidio JF. Stigma of psychological therapy: Stereotypes, interpersonal reactions, and the self-fulfilling prophecy. J Couns Psychol 1986; 33(2): 148-154. [ Links ]

23. Vogel DL, Wade NG, Haake S. Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. J Couns Psychol 2006; 53(3): 325-337. [ Links ]

24. Yamawaki N. Differences between Japanese and American college students in giving advice about help seeking to rape victims. J Soc Psychol 2007; 147(5): 511-530. [ Links ]

25. Mansfield AK, Addis ME, Mahalik JR. 'Why won't he go to the doctor?': The psychology of men's help seeking. Int J Mens Health 2003; 2(2): 93-109. [ Links ]

26. Ang RP, Lim KM, Tan A, Yau TY. Effects of gender and sex role orientation on help-seeking attitudes. Curr Psychol 2004; 23(3):203-214. [ Links ]

27. Vogel DL, Wester SR. To seek help or not to seek help: The risks of self-disclosure. J Couns Psychol 2003; 50(3): 351-361. [ Links ]

28. Lundervold DA, Young LG. Older adults' attitudes and knowledge regarding use of mental health services. J Clin Exp Gerontol 1992; 14(1): 45-55. [ Links ]

29. Segal DL, Coolidge FL, Mincic MS, O'Riley A. Beliefs about mental illness and willingness to seek help: A cross-sectional study. Aging Ment Health 2005; 9(4): 363-367. [ Links ]

30. Berger JM, Levant R, McMillan KK, Kelleher W, Sellers A. Impact of gender role conflict, traditional masculinity ideology, alexithymia, and age on men's attitudes toward psychological help seeking. Psychology of Men & Masculinity 2005; 6(1): 73-78. [ Links ]

31. Nakane Y, Jorm AF, Yoshioka K, Christensen H, Nakane H, Griffiths KM. Public beliefs about causes and risk factors for mental disorders: A comparison of Japan and Australia. BMC Psychiatry 2005; 5. [ Links ]

32. Tanioka I, Nitta M, Iwai N, Yasuda T. (2007). Japanese General Social Survey (JGSS), 2005 [Computer file]. ICPSR04703-v1. Osaka, Japan: Osaka University of Commerce, Institute of Regional Studies [producer], 2007. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2007-08-13. doi:10.3886/ICPSR04703 [ Links ]

33. Fischer EH, Turner JI. Orientations to seeking professional help: Development and research utility of an attitude scale. J Consult Clin Psychol 1970; 35(1): 79-90. [ Links ]

34. Leong FTL, Zachar P. Gender and opinions about mental illness as predictors of attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. Brit J Guid Couns 1999; 27(1): 123-132. [ Links ]

35. Morgan T, Ness D, Robinson M. Students' help-seeking behaviours by gender, racial background, and student status. Can J Counsell 2003; 37(2): 151-166. [ Links ]

36. Kaneko Y, Motohashi Y, Sasaki H, Yamaji M. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and related risk factors for depressive symptoms among elderly persons living in a rural Japanese community: A cross-sectional study. Community Ment Health J 2007; 43(6): 583-590. [ Links ]

37. Currin JB, Hayslip B, Jr., Schneider LJ, Kooken RA. Cohort differences in attitudes toward mental health services among older persons. Psychother Theor Res Pract Train 1998; 35(4): 506-518. [ Links ]

38. Lebowitz BD, Niederehe G. Concepts and issues in mental health and aging. In: Birren JE, Sloane RB, Cohen GD, editors. Handbook of mental health and aging, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Borun Center for Gerontolgical Research; 1992. [ Links ]

39. Crabb R, Hunsley J. Utilization of mental health care services among older adults with depression. J Clin Psychol 2006; 62(3): 299-312. [ Links ]

40. Jang Y, Kim G, Hansen L, Chiriboga DA. Attitudes of older Korean Americans toward mental health services. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55(4): 616-620. [ Links ]

41. Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Raue P, Friedman SJ, et al. Perceived stigma as a predictor of treatment discontinuation in young and older outpatients with depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158(3): 479-481. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Niwako Yamawaki

Department of Psychology

Brigham Young University

1001 Spencer W. Kimball Tower

Provo, UT 84602

E-mail: niwako_yamawaki@byu.edu

Received: 22 March 2010

Revised: 21 October 2010

Accepted: 22 December 2010