Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The European Journal of Psychiatry

versión impresa ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.27 no.4 Zaragoza oct./dic. 2013

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0213-61632013000400004

Seeking professional help for nightmares: A representative study

Michael Schredl

Central Institute of Mental Health, Medical Faculty Mannheim/Heidelberg University. Germany

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: Nightmares are defined as disturbing mental experiences that generally occur during REM sleep and often result in awakening. Even though about 5% of the general population suffers from nightmares, little is known about seeking professional help in this patient group.

Methods: A quota sample of 2019 participants representative for the German population was studied.

Results: The findings indicate that every eighth person with frequent nightmares (cutoff: every other week or more often) sought at one time of his/her life for professional help for coping with nightmares. Socio-demographic variables did not correlate with help-seeking behavior.

Conclusions: Nightmares are an undertreated condition and future studies should aim at a more throughout understanding why nightmare sufferers rarely seek help for their condition.

Key words: Nightmares; Treatment; Representative sample.

Introduction

Nightmares are defined as disturbing mental experiences that generally occur during REM sleep and often result in awakening (ICSD-2; AASM)1. In representative samples about 5% of the participants stated that they suffer from nightmares2-5. Even though frequent nightmares are associated with poor sleep quality6 and impaired day-time functioning7,8, the clinical impression is that most nightmare sufferers do not seek professional help for their problems9. Even in sleep clinics, nightmares were rarely diagnosed and treated: Krakow10 reported that 16.3% of sleep-disordered patients (N = 718) also have a salient nightmare condition that would normally not have been diagnosed if he hadn't specifically asked for it. Similar, Schredl, Binder11 found that 13.4% of patients under-going diagnostic procedures in a sleep laboratory (N = 4.001) reported nightmares at least once a week; an explicit diagnosis of a nightmare disorder was given to 1.6% of the sample. These studies indicate that nightmares are underdiagnosed and very likely undertreated12-14. However, up to now, there is no systematic research identifying the frequency of nightmare sufferers seeking professional help for their disorder - despite its consequences on sleep and day-time functioning.

The aim of the present study was to fill this gap and to investigate how often persons with nightmares in a representative sample seek professional help for coping with their nightmares. It was expected that nightmare frequency and indicators of nightmare severity would increase the probability of seeking professional help. The present data analyses are an extension of a previous report focusing on nightmare frequency and nightmare topics15.

Method

Measurement instruments

For eliciting nightmare frequency, a seven-point frequency scale (coded from 0 = never, 1 = very rarely, 2 = several times a year, 3 = about once a month, 4 = about once in two weeks, 5 = about once a week, 6 = several times a week) was used in the study. The following nightmare definition was given: strongly negatively-toned dreams with fear or panic resulting in immediate awakening. Within this survey, the frequency of negatively-toned dreams without specific definition was also elicited using a similar scale. This scale was not included in the present analyses but used for selecting the subsample that suffers from bad dreams and/or nightmares. In addition, the participants were asked the following question: "My dreams have sometimes been so intense that I could not stop thinking about them the following day" (Yes/No). This could be conceptualized as an indicator for nightmare severity as more intense dreams with negative emotions have a stronger effect on the subsequent day16.

To a subsample (persons who reported nightmares [see above definition] and/or negatively-toned dreams at least several times per year) the following two questions were presented: (1) "I often have worries prior to bedtime due to my frequent nightmares" (Yes/No) and (2) "I have sought professional help for coping with my nightmares" (Yes/No).

The following socio-demographic variables were included in the study: age, gender, education (five levels: "primary school" (9 years school), "primary school and completed apprenticeship" (9 years school plus apprenticeship), "Realschule" (10 years school), "Abitur" (13 years school). "Abitur with completed studies" (13 years school plus university degree)), social class (5 levels based on the total income of the household, the educational level, and the profession of the head of the household), size of town of residence (10 levels starting from (1) towns with less than 2000 inhabitants to (10) cities with more than 500,000 inhabitants), and marital status (married/living with partner, single/living without partner).

Participants and procedure

Overall, a representative sample (that included persons over 14 years of age) of 2019 persons (1135 women, 884 men) was drawn from German households. The study was carried out by GfK Marktforschung, Nürnberg, Germany and was financed by Wort & Bild Verlag, München, Germany. The quota sample was representative for the German population. About 500 interviewers in different locations all over Germany (representative for the 16 German states and the variety of town sizes) received a list of four to five randomly generated combinations of the six stratification criteria: age group (14-19, 20-29, etc.) gender, number of persons in the household, federal state (of the 16 German federal states), town of residence size (less than 5,000, 5,000 to 19,999, 20,000 to 99,999, 100,000 or more), and occupation of the head of the household (blue-collar worker, employee, civil servant, self-employed/freelance, without occupation like a student, unemployed, and retired). The participants were selected by the interviewer with regard to the four or five combinations s/he received. The interviewers were trained by GfK Marktforschung. The nightmare questions were part of a multi-topic survey mainly focused on the evaluation of consumer products of different brands.

The mean age of the sample was 46.4 years (SD = 16.9). The subsample reporting nightmares and/or bad dreams at least several times a year consisted of 1022 persons (623 women, 399 men) with the mean age of 45.9 ± 17.2 yrs. The range varied from 14 years to 92 years. Participants were interviewed face-to-face at home. After being instructed by the interviewer, the section with the nightmare questions was filled out on a laptop without further interaction with the interviewer.

Due to problems of the interviewers not completing their recruiting aim (e.g., due to illness since the time interval for collecting the data was only two weeks), the resulting data set does not exactly match the representativeness of the lists sent to the interviewers. For an estimation of this effect, weights were computed, 90% were within the range of 0.40 to 1.87. Data analyses were carried out with the SAS 9.2 software package for Windows. To analyze the effects of socio-demographic variables, nightmare frequency, and the daytime effects of dreams on the "seeking help for nightmares" variable (binary), a logistic regression procedure was used.

Results

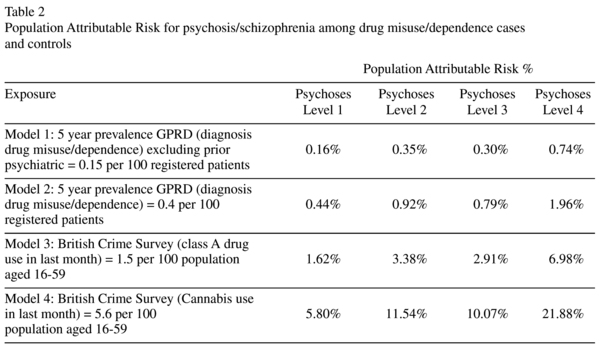

Overall, 3.03% of the participants with at least some nightmares and/or bad dreams (N = 1022) reported that they sought professional help for coping with their nightmares. Percentages of the "Seeking professional help" item for each nightmare category are depicted in Table 1. Combining the first three categories, 15.19% of the persons with nightmares about every other week or more often stated that they sought professional help. The statistical analysis showed that none of the socio-demographic variables affected help-seeking and only nightmare frequency and the self-rated effects of dreams on subsequent waking life were significantly associated with the probability of seeking professional help (see Table 2). Specifically, if the person stated that dreams affected their waking life, the more likely the person sought help for his or her nightmares.

In the subsample of persons with nightmares and/or bad dreams (N = 1022) 38.65% of the participants stated that their dreams sometimes have been so intense that they could not stop thinking about them the following day. In addition, 4.40% of the subsample (N = 1022) reported worrying about nightmares before bedtime. Out of this subgroup (N = 45), 35.56% reported that they have sought professional help.

Discussion

This is the first study providing data about the percentage of persons with nightmares seeking professional help for this disorder. Prior to discussing the finding in detail it is necessary to take a look on the limitations of this study. The item measuring whether the person sought help for his/her nightmares did not include any time frame; this means that the person could have sought help recently or ten or twenty years ago but still ha-ve nightmares. One also has to keep in mind that nothing was elicited about whether the professional help had any beneficial effect on nightmare frequency. It might be speculated that the effect was minor because current nightmare frequency correlated with seeking professional help in the past.

Moreover, if the list given to the interviewers would have been completed without any missing combinations by every interviewer, the present data set would be representative. Due to missing data sets, this aim was not achieved. As most of the weights were within a reasonable range, the data set is still close to being representative (for a more detailed discussion regarding random sampling procedures [problem with availability and rejection] and quota-based samples, see Noelle-Neumann and Petersen17).

Since the study was carried out in Germany, the present findings might be limited to the German health system, implying that patients most often ask the general practitioner for help with this disorder - as for mental disorder in general18. Whether the patient is referred to a psychotherapist or a psychiatrist depends strongly on the knowledge of the general practitioner about nightmares and their etiology. In the present study, nothing was elicited about other mental disorders that might be associated with the nightmares like depression or posttraumatic-stress disorder. As the five most common nightmare topics found in this sample, Falling, Being chased, Being paralyzed, Being late, Close persons disappear/die15 were indicative for idiopathic nightmares19, it can be argued that the proportion of persons suffering from post-traumatic nightmares are quite small. It would be, however, of great value if future studies include measures of psychopathology and PTSD symptomatology.

In addition, the given nightmare definition does not completely rule out the possibility that some participants with night terrors gave false positive answers. As night terrors are rare in adulthood, this possible bias should be small. Nevertheless it would be interesting to measure night terror frequency and -in a way similar to the present study- whether the patient had sought help for his or her condition. As stated above, the presence of a psychiatric disorder like depression or an anxiety disorder was not elicited in this survey. This might be a confounder regarding the findings as patients with mental disorders suffer quite often from a co-morbid nightmare disorder20, even though one might argue that we asked specifically for seeking help for nightmares, and there is no reason why patients with mood or anxiety disorders should seek explicitly help for nightmares and not for their mental disorder. A recent study21 showed that imagery rehearsal is very effective in depressed patients with a co-morbid nightmare disorder.

About every eighth person with nightmares (cutoff: every other week or more often) sought at one time of his/her life for professional help for coping with nightmares; the contention that nightmares are undertreated9 is supported by this data, in particular as the percentage of successfully treated nightmare sufferers is presumably much smaller. As expected, nightmare frequency was the most important factor explaining help-seeking behavior. It is also very plausible that the effect of dreams on waking life play an additional role because the nightmares impair daytime functioning in these persons more strongly. This fits in with a previous finding that dreams incorporating negatively toned events of the previous day have a stronger effect on the mood of the next day16. In order to measure the waking-life distress attributed to nightmares, it would be advisable to use a nightmare distress scale in future studies.

Interestingly, none of the socio-demographic variables had an effect on help-seeking if nightmare frequency was controlled. As nightmares are discussed as a potential risk factor for suicide22-24 and their negative effect on daytime functioning8, it would be desirable to study in more detail the reasons why nightmare sufferers do not seek professional help. One might speculate that adults who suffered from nightmares since childhood -a high percentage of adult nightmare sufferers state that nightmares started in childhood25- perceive them as "normal" despite the burden of the disorder. Another speculation is that the general practitioner or even psychotherapists/psychiatrists are not aware of the effectiveness of simple cognitive interventions like the imagery rehearsal treatment26.

To summarize, the present study indicates that nightmares are an undertreated condition. Future studies should aim at a more thorough understanding of why nightmare sufferers rarely seek help for their condition. Internet-based self-help programs27, for example, might help increase the percentage of treated nightmare sufferers -within a concept of stepped care- since not every patient accepts individual psychotherapy.

References

1. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The international classification of sleep disorders. (ICSD-2). Westchester: AASM; 2005. [ Links ]

2. Bixler EO, Kales A, Soldatos CR, Kales JD, Healey S. Prevalence of sleep disorders in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. Am J Psychiatry 1979; 136: 1257-1262. [ Links ]

3. Stepansky R, Holzinger B, Schmeiser-Rieder A, Saletu B, Kunze M, Zeitlhofer J. Austrian dream behavior: results of a representative population survey. Dreaming 1998; 8: 23-30. [ Links ]

4. Hublin C, Kaprio J, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M. Nightmares: familial aggregation and association with psychiatric disorders in a nationwide twin cohort. Am J Med Genet (Neuropsychiat Genet) 1999; 88: 329-336. [ Links ]

5. Bjorvatn B, Grønli J, Pallesen S. Prevalence of different parasomnias in the general population. Sleep Medicine 2010; 11(10): 1031-1034. [ Links ]

6. Schredl M. Effects of state and trait factors on nightmare frequency. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003; 253: 241-247. [ Links ]

7. Köthe M, Pietrowsky R. Behavioral effects of nightmares and their correlations to peronality patterns. Dreaming 2001; 11: 43-52. [ Links ]

8. Li SX, Zhang B, Li AM, Wing YK. Prevalence and correlates of frequent nightmares: a community-based 2-phase study. Sleep 2010; 33: 774-780. [ Links ]

9. Schredl M. Nightmares: An under-diagnosed and undertreated condition? Commentary on Li et al. Prevalence and correlates of frequent nightmares: a community-based 2-phase study. Sleep 2010; 33: 733-734. [ Links ]

10. Krakow B. Nightmare complaints in treatment-seeking patients in clinical sleep medicine settings: diagnostic and treatment implications. Sleep 2006; 29: 1313-1319. [ Links ]

11. Schredl M, Binder R, Feldmann S, Göder R, Hoppe J, Schmitt J, et al. Dreaming in patients with sleep disorders: A multicenter study. Somnologie 2012; 16: 32-42. [ Links ]

12. Aurora RN, Zak RS, Auerbach SH, Casey KR, Chowdhuri S, Karippot A, et al. Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. J Clin Sleep Med 2010; 6: 389-401. [ Links ]

13. Krakow B, Zadra A. Imagery Rehearsal Therapy: Principles and Practice. Sleep Med Clinics 2010; 5: 289-298. [ Links ]

14. Mayer G, Fischer J, Penzel T, Riemann D, Rodenbeck A, Sitter H, et al. S3-Leitlinie - Nicht erholsamer Schlaf. Somnologie 2009; 13(Suppl 1): 1-106. [ Links ]

15. Schredl M. Nightmare frequency and nightmare topics in a representative German sample. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2010; 260: 565-570. [ Links ]

16. Schredl M, Reinhard I. The continuity between waking mood and dream emotions: Direct and second-order effects. Imagin Cogn Pers 2009-2010; 29: 271-282. [ Links ]

17. Noelle-Neumann E, Petersen T. Alle, nicht jeder. Einführung in die Methode der Demoskopie. Berlin: Springer; 2000. [ Links ]

18. Dezetter A, Briffault X, Bruffaerts R, Graaf R, Alonso J, König HH, et al. Use of general practitioners versus mental health professionals in six European countries: the decisive role of the organization of mental health-care systems. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013; 48(1): 137-149. [ Links ]

19. Wittmann L, Schredl M, Kramer M. The role of dreaming in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychother Psychosom 2007; 76: 25-39. [ Links ]

20. Swart ML, van Schagen AM, Lancee J, van den Bout J. Prevalence of Nightmare Disorder in Psychiatric Outpatients. Psychother Psychosom 2013; 82(4): 267-268. [ Links ]

21. Thünker J, Pietrowsky R. Effectiveness of a manualized imagery rehearsal therapy for patients suffering from nightmare disorders with and without a comorbidity of depression or PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2012; 50(9): 558-564. [ Links ]

22. Bernert RA, Joiner TE, Cukrowicz KC, Schmidt NB, Krakow B. Suicidality and sleep disorders. Sleep 2005; 28: 1135-1141. [ Links ]

23. Agargun MY, Besiroglu L, Cilli AS, Gulec M, Aydin A, Inci R, et al. Nightmares, suicide attempts, and melancholic features in patients with unipolar major depression. J Affect Disord 2007; 98(3): 267-270. [ Links ]

24. McCall WV, Batson N, Webster M, Case LD, Joshi I, Derreberry T, et al. Nightmares and dysfunctional beliefs about sleep mediate the effect of insomnia symptoms on suicidal ideation. J Clin Sleep Med (Comparative Study Multicenter Study). 2013; 9(2): 135-140. [ Links ]

25. Kales A, Soldatos CR, Caldwell A, Charney D, Kales JD, Markel D, et al. Nightmares: clinical characteristics and personality pattern. Am J Psychiatry 1980; 137: 1197-1201. [ Links ]

26. Hansen K, Höfling V, Kröner-Borowik T, Stangier U, Steil R. Efficacy of psychological interventions aiming to reduce chronic nightmares: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2013; 33(1): 146-155. [ Links ]

27. Lancee J, Spoormaker VI, Van den Bout J. Long-term effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural self-help intervention for nightmares. J Sleep Res 2011; 20(3): 454-459. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr. M. Schredl

Schlaflabor Zentralinstitut für Seelische Gesundheit

Postfach 12 21 20, 68072 Mannheim, Germany

Telefone: + +49/621/1703-1782

Fax: + +49/621/1703-1785

E-mail: Michael.Schredl@zi-mannheim.de

Received: 15 March 2013

Revised: 26 August 2013

Accepted: 29 September 2013