Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The European Journal of Psychiatry

versión impresa ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.30 no.2 Zaragoza abr./jun. 2016

Do the generalised cognitive deficits observed in schizophrenia indicate a rapidly-ageing brain?

Milan Dragovica,d; Stanislav Fajgeljb and Alexander Panickacheril Johna,c,d

a Clinical Research Centre, North Metropolitan Health Service - Mental Health, Perth. Australia

b Union University, Belgrade. Serbia

c Bentley Health Service, Perth. Australia

d School of Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, The University of Western Australia, Perth. Australia

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: The nature and pattern of cognitive deficits (CD) in schizophrenia and whether the deficits are generalised or domain specific continues to be debated vigorously. We ascertained the pattern of CD in schizophrenia using a novel statistical approach by comparing the similarity of cognitive profiles of patients and healthy individuals.

Methods: In a consecutive sample of 78 patients with schizophrenia, performance on six cognitive domains (verbal memory, working memory, motor speed, processing speed, verbal fluency and executive functions) was measured using the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS). The similarity of cognitive profile between patients and two groups of healthy controls (age-matched and older adults who were in the age group of 70-79) was evaluated using a special purpose-built macro.

Results: Cognitive performance profiles in various domains of patients with schizophrenia and age-matched controls were markedly similar in shape, but differed in the overall performance, with patients performing significantly below the healthy controls. However, when the cognitive profiles of patients with schizophrenia were compared to those of older adult controls, the profiles remained similar whilst the overall difference in performance vanished.

Conclusions: Cognitive deficit in schizophrenia appears to be generalised. Resemblance of cognitive profiles between patients with schizophrenia and older adult controls provides some support for the accelerated ageing hypothesis of schizophrenia.

Keywords: Cognition; Schizophrenia; Premature ageing.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a neurobiological disorder characterised by positive, negative, mood and motor symptoms, prominent neurocognitive and social cognitive deficits, and significantly impaired functioning in many realms1,2,3. Consistent evidence through research carried out in the past few decades supports the universality of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia and cognitive changes are considered as fundamental features of this condition4,5,6. The relevance of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia is further enhanced by the findings that they are robust predictors of patients' community functioning and their treatment outcomes, thus contributing further to the overall burden of the disorder7,8. Despite these, cognitive impairments in schizophrenia continue to be conceptualised as a secondary phenomenon and diagnostically uninformative, and recent exhortations to incorporate them into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual volume 5 (DSM-V) diagnostic apparatus were not successful9-11.

Even though the core clinical characteristics and the heterogeneity of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia have been widely scrutinized over the last few decades12-14, final agreement on the true nature of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia is still missing. In this area of research two contrasting views have crystallised over the last few decades: a) generalised deficit of cognition, whereby patients perform poorly on a range of cognitive tests 6,12,15, and b) specific or differential deficits, whereby patients perform poorly on some but not on all cognitive tests 7,16-19. Others have conceptualised cognitive deficits as a cardinal feature of a sub-group of schizophrenia patients13, 20, evoking the old concept of dementia praecox21. Both generalised and domain specific views have depended for support on differing cognitive assessment tools, the heterogeneity of schizophrenia samples, comorbidity issues, treatment outcomes, and other less well defined facets of cognition such as emotional and/or social intelligence. The way data are analysed and/or interpreted also determines the conceptual framework: using a cognitive battery and traditional analysis of variance approach, followed by numerous unplanned post-hoc comparisons22, the emphasis on single task differences (i.e., differential deficit) may prevent researchers from seeing the elephant in the room, i.e., the fact that patients exhibit consistent deterioration of performance across the remaining cognitive domains.

In the present study we adopt a novel analytical approach to the old question of generalised versus specific cognitive deficit. In particular, we focus on the examination of similarities in cognitive performance between schizophrenia patients and healthy controls, rather than on fluctuation of performance within the study groups. Specifically, we evaluated the parallelismof cognitive profiles of schizophrenia patients and two cohorts of healthy controls, age matched and older adult controls.

Methods

We collated from the medical records to retrospectively cognitive function data of a consecutive sample of 78 patients with schizophrenia admitted during the period from August 2010 to October 2014 to a medium length of stay, tertiary care treatment and rehabilitation unit located at Bentley Health Service, Western Australia. Diagnoses were generated after detailed clinical interview and observation utilising ICD-10 Criteria by a senior psychiatrist who was the clinical lead of the unit and was quite familiar with the patients. Cognitive function was measured using the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS)23,24. The study was approved by the local institutional ethics committee. In most cases evaluation of cognitive function assessments were carried out within a week of the patient's admission to the unit.

BACS is a brief pencil and paper cognitive assessment instrument, taking approximately 35 minutes to administer, and measuring four of the seven neurocognitive domains recognised as relevant for measurement in schizophrenia by the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) consortium2,25,26: reasoning and problem solving, processing speed, verbal memory, and working memory. The BACS was designed for ease of administration and scoring, and has higher acceptance by patients and demonstrated robust reliability and concurrent validity when compared against lengthy standard batteries of neuropsychological tests 23,24. The six sub-tests include List learning (LL; verbal memory), Digit sequencing (DS; working memory), Token motor task (TMT; motor speed), Verbal fluency (VF; processing speed), Digit symbol coding (DSC; attention and processing speed) and Tower of London (ToL; reasoning and problem solving). Norms are organised in a manner that will allow the calculation of standardised scores adjusted for age and sex for each test, and for overall composite scores. The mean score of healthy controls was set as 0 and the standard deviation (SD) to 1. Cognitive profiles of the control subjects were adopted from a large normative study24 which ascertained subjects randomly from the general community using a rigorous survey sampling procedure. Control subjects were screened using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders and were excluded if lifetime and past month history of alcohol or illicit substance use was observed. An additional inclusion criterion was to have English as primary language. Demographically, this sample was representative of the U.S. population, as in the 2005 U.S. census data, providing thus a "realistic comparison to clinical samples, especially patients with schizophrenia" 24 (p. 110).

Conventional data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 22. Profile analysis was conducted using a special purpose macro developed by one of the authors of this study. This macro is available free of charge and can be downloaded from [http://www.stanef.in.rs]. Profile distances were examined by calculating Euclidean (raw) and Mahalanobis' (standardised) distances27, while the similarity of cognitive profiles was estimated by calculating intraclass coefficients of correlations28 (ICC).

Results

Profile analyses

There were 94 admissions to the unit between the ages of 18 and 65 with the ICD-10 diagnosis of schizophrenia during the period from August 2010 to September 2014. BACS evaluation was not conducted or completed for 16 patients due reasons such as non-fluency with English, refusal to undergo the test, or test administration deemed not appropriate due to clinical reasons. The demographic and clinical information about sample used in this study are presented in Table 1.

The overall differences of cognitive profiles between patients and controls were evaluated. First, we compared cognitive profiles of schizophrenia patients and age matched (20-59 years) healthy controls, and then compared cognitive profiles between patients and older adult healthy controls (age range 70-79)24. Comparison of cognitive profiles between schizophrenia patients and age-matched controls demonstrated significantly lower scores on the set of BACS measures for schizophrenia patients. In contrast, the overall difference among groups was not significant when the cognitive profile of schizophrenia patients was compared to that of the older adult controls (age range 70-79 years). Raw and standardised distance estimates are presented in Table 2.

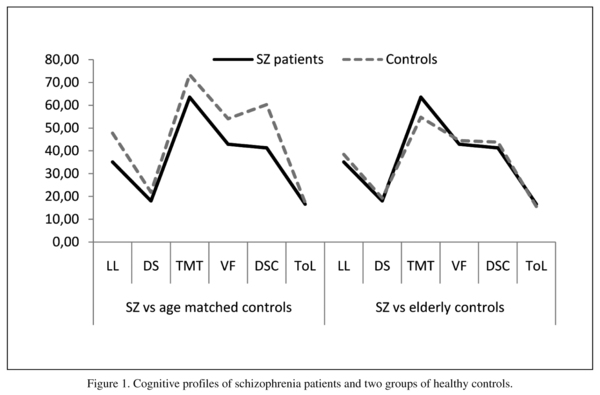

Similarity of cognitive profiles between schizophrenia patients and healthy controls (age-matched and older adult controls) was investigated by calculating Intraclass coefficients of correlation. This statistical procedure can also be interpreted as the test of parallelism of profiles, i.e. whether groups of study participant exhibit similar patterns of highs and lows on the set of commensurate measures. There was a significant resemblance between the cognitive profiles of schizophrenia patients and healthy controls (20-59 years), ICC = 0.947, 95%CI (0.76-0.99), p < 0.001). Similarity of cognitive profiles was even stronger between schizophrenia patients and older adult controls, ICC = 0.963, 95%CI (0.83-0.99), p < 0.0001. Figure 1 demonstrates cognitive profile jointly presented for all groups using the mean raw scores.

Exploratory factor analysis

Principal component axis factoring based on eigenvalues greater than 1 was used to investigate the underlying structure of cognitive domains. First, we examined if data were suitable for factor analysis. Both tests, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO = 0.818), and the Bartlett's test of sphericity (Chi-square = 167.1, p < 0.001) indicated that data were highly suitable for factor analysis. A single principal component (the only one with eigenvalue exceeding 1) accounting 55.9% of the variance was identified as underlying six cognitive domains (Table 3). Individual sub-tests had similar loadings for the single principal component.

Discussion

Results obtained in the present study, using a variety of statistical procedures, all indicate that cognitive deficit in our sample of schizophrenia patients is generalised. First, conventional exploratory factor analysis confirms that performance on various cognitive tests was mediated through a single underlying cognitive dimension. The estimated factor loadings had similar magnitude, implying that each sub-test has almost equally contributed to the general cognitive factor. Factor analytic results are therefore supportive of the generalised deficit hypothesis 6,12,15,29,30. Second, we provide converging evidence that cognitive profiles between schizophrenia patients and heathy controls are strikingly similar, even though they differ significantly in the overall performance12.

Patients occasionally show some fluctuation of performance relative to healthy controls, but this does not dispute a clear parallelism of the cognitive profiles. For example, performance of patients on the Tower of London task (executive control) reveals that patients performed fairly similar to age-mat-ched healthy controls (Figure 1). This unexpected similarity however, can be a result of a psychometric artefact or inability of this particular task to discriminate successfully performance of patients and controls (ceiling effect), i.e., the mean scores of both groups were close to the maximum raw score of 22 for this sub-test. Availability of the age stratified normative data for the BACS24 has added further impetus to the understanding of cognitive profile of schizophrenia patients relative to healthy controls.

There are some limitations to this study. The BACS evaluates only four out of seven cognitive domains incorporated in the MATRICS battery and in particular social cognitive deficits are not measured25,26. Also, the sample size in the present study is not as large as recommended by rule-of-thumb metrics. For example, Tabachnick and Fidell (2007) suggest31 300 cases, while others32 maintain that sample to variable ratio can be as low as 6:1. We are confident that our sample is large enough to fulfil the requirements for conducting factor analysis. Importantly, identified latent structures in both samples are reasonably similar. We also acknowledge that we compared cognitive profiles using two samples from geographically distinct populations. However, as both populations are from similar socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds, we believe sampling did not confound our results. As in many research fields, the best protection of the type II error is an independent replication of the present study, which we encourage.

Of particular interest in the present study is the resemblance of cognitive profiles between schizophrenia patients and older adult controls (70-79 years old) despite substantial age differences. The closeness of cognitive profiles is consistent with the concept of schizophrenia as a disorder of accelerated cognitive and functional decline21. In modern terms, the old concept of dementia praecox brings to mind the premature ageing hypothesis in schizophrenia33. In brief, this hypothesis postulates that in people affected with schizophrenia, some physiological changes occur earlier. These include metabolic abnormalities34, cardiovascular problems35, brain abnormalities36, cerebral white matter changes37, and shorter telomeres compared to healthy subjects38, leading to a lifespan 20-25 years shorter than the general population. However, pathophysiology of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia might be distinct from pathophysiology that underpins cognitive decline in normal subjects, e.g., powerful life style factors such as substance abuse (illicit and licit drugs), diet, and sedentary life style and social withdrawal.

Due to absence of our own control sample, in this study we were dependent on the normative data for healthy controls from other studies. This fact somewhat limits the generalisability of our results. However, we believe our choice of the normative control sample is reasonable: to our best knowledge, Keefe et al (2008) 24 provided the only normative data for the BACS which are age stratified, and which are representative of the general population. Second, we are aware that our sample of schizophrenia patients (n = 78) and, especially older adult control (n = 50) are rather small than large for this type of analysis. Hence, we strongly encourage replication of this study. The analytical tool (SPSS macro) is freely available and, with minor modifications, should be used in similar studies.

References

1. Black D, Andreasen N. Introductory textbook of psychiatry. USA: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc; 2014. [ Links ]

2. Buchanan RW, Keefe RS, Umbricht D, Green MF, Laughren T, Marder SR. The FDA-NIMH-MATRICS guidelines for clinical trial design of cognitive-enhancing drugs: what do we know 5 years later? Schizophr Bull. 2011; 37(6): 1209-17. [ Links ]

3. van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009; 374 (9690): 635-45. [ Links ]

4. Green FM, Neuchterlein HK. Should schizophrenia be treated as a neurocognitive disorder? Schizophr Bull. 1999; 25(2): 309-18. [ Links ]

5. Palmer BW, Dawes SE, Heaton RK. What do we know about neuropsychological aspects of schizophrenia? Neuropsychol Rev. 2009; 19(3): 365-84. [ Links ]

6. Schaefer J, Giangrande E, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D. The global cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: consistent over decades and around the world. Schizophr Res. 2013; 150(1): 42-50. [ Links ]

7. Green MF, Kern RS, Heaton RK. Longitudinal studies of cognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: implications for MATRICS. Schizophr Res. 2004; 72: 41-51. [ Links ]

8. Rajji TK, Miranda D, Mulsant BH. Cognition, function, and disability in patients with schizophrenia: a review of longitudinal studies. Can J Psychiatry. 2014; 59(1): 13-7. [ Links ]

9. Keefe RS, Fenton WS. How should DSM-V criteria for schizophrenia include cognitive impairment? Schizophr Bull. 2007; 33(4): 912-20. [ Links ]

10. Keefe RSE. Should cognitive impairment be included in the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia? World Psychiatry 2008; 7(1): 22-8. [ Links ]

11. Tandon R, Maj M. Nosological status and definition of schizophrenia: some considerations for DSM-V and ICD-11. Asian J Psychiatr. 2008; 1(2): 22-7. [ Links ]

12. Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK. Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology. 1998; 12(3): 426-45. [ Links ]

13. Hallmayer JF, Kalaydjieva L, Badcock B, Dragovic M, Howell S, Michie P, et al. A subtype of schizophrenia characterised by pervasive cognitive deficit has distinct genetic basis. Am J Hum Genet. 2005; 77(3): 468-76. [ Links ]

14. Seaton BE, Goldstein G, Allen DN. Sources of heterogeneity in schizophrenia: the role of neuropsychological functioning. Neuropsychol Rev. 2001; 11(1): 45-67. [ Links ]

15. Dickinson D, Ragland JD, Gold JM, Gur RC. General and specific cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: Goliath defeats David? Biol Psychiatry. 2008; 64(9): 823-7. [ Links ]

16. Gold JM, Hahn B, Strauss GP, Waltz JA. Turning it upside down: areas of preserved cognitive function in schizophrenia. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009; 19(3): 294-311. [ Links ]

17. Horan WP, Foti D, Hajcak G, Wynn JK, Green MF. Intact motivated attention in schizophrenia: evidence from event-related potentials. Schizophr Res. 2012; 135(1-3): 95-9. [ Links ]

18. Rajji TK, Voineskos AN, Butters MA, Miranda D, Arenovich T, Menon M, et al. Cognitive performance of individuals with schizophrenia across seven decades: a study using the MATRICS consensus cognitive battery. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013; 21(2): 108-18. [ Links ]

19. Green MF, Horan WP, Sugar CA. Has the generalized deficit become the generalized criticism? Schizophr Bull. 2013; 39: 257-62. [ Links ]

20. Green JM, Cairns JM, Wu J, Dragovic M, Jablensky A, Tooney AP, et al. Genome-wide supported variant MIR137 and severe negative symptoms predict membership of an impaired cognitive subtype of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2013; 18(7): 774-80. [ Links ]

21. Kraepelin E. Dementia praecox and paraphrenia: Krieger Publishing Company; 1971. [ Links ]

22. Schretlen DJ, Cascella NG, Meyer SM, Kingery LR, Testa SM, Munro CA, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2007; 62(2): 179-86. [ Links ]

23. Keefe RS, Goldberg TE, Harvey PD, Gold JM, Poe MP, Coughenour L. The Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia: reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophr Res. 2004; 68(2): 283-97. [ Links ]

24. Keefe R S, Harvey PD, Goldberg TE, Gold JM, Walker TM, Kennel C, et al. Norms and standardization of the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS). Schizophr Res. 2008; 102(1-3): 108-115. [ Links ]

25. Kern RS, Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Baade LE, Fenton WS, Gold JM, et al. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 2: co-norming and standardization. Am J Psychiatry. 2008; 165(2): 214-20. [ Links ]

26. Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, Baade LE, Barch DM, Cohen JD, et al. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2008; 165(2): 203-13. [ Links ]

27. Mahalanobis PC. On the generalized distance in statistics. Calcutta: National Institute of Sciences; 1936. [ Links ]

28. McGraw KO, Wong SP. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol Methods. 1996; 1(1): 30. [ Links ]

29. Fucetola R, Seidman LJ, Kremen WS, Faraone SV, Goldstein JM, Tsuang MT. Age and neuropsychologic function in schizophrenia: a decline in executive abilities beyond that observed in healthy volunteers. Biol Psychiatry. 2000; 48(2): 137-46. [ Links ]

30. Keefe RS, Bilder RM, Harvey PD, Davis SM, Palmer BW, Gold JM, et al. Baseline neurocognitive deficits in the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006; 31(9): 2033-46. [ Links ]

31. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. Boston: Pearson Education Inc; 2007. [ Links ]

32. Gorsuch RL. Exploratory factor analysis: its role in item analysis. J Pers Assess. 1997; 68(3): 532-60. [ Links ]

33. Kirkpatrick B, Messias E, Harvey PD, Fernandez-Egea E, Bowie CR. Is schizophrenia a syndrome of accelerated aging? Schizophr Bull. 2008; 34(6): 1024-32. [ Links ]

34. John PA, Koloth R, Dragovic M, Lim S. Increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Australians with severe mental illness. Med J Aust. 2009; 190(4): 176-9. [ Links ]

35. Hennekens CH, Hennekens AR, Hollar D, Casey DE. Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2005; 150(6): 1115-21. [ Links ]

36. Koutsouleris N, Davatzikos C, Borgwardt S, Gaser C, Bottlender R, Frodl T, et al. Accelerated brain aging in schizophrenia and beyond: a neuroanatomical marker of psychiatric disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2014; 40(5): 1140-53. [ Links ]

37. Kochunov P, Glahn DC, Rowland LM, Olvera RL, Winkler A, Yang YH, et al. Testing the hypothesis of accelerated cerebral white matter aging in schizophrenia and major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2013; 73(5): 482-91. [ Links ]

38. Fernandez-Egea E, Bernardo M, Heaphy CM, Griffith JK, Parellada E, Esmatjes E, et al. Telomere length and pulse pressure in newly diagnosed, antipsychotic-naive patients with nonaffective psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2009; 35(2): 437-42. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr Milan Dragovic, PhD

Clinical Research Centre

Private Mail Bag 1

Mount Claremont

WA 6010, Perth, Australia

Tel.: +61 8 9347 6442

Fax: +61 8 9384 5128

Email: milan.dragovic@health.wa.gov.au

Received: 23 October 2015

Revised: 17 February 2016

Accepted: 18 February 2016