Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Cirugía Plástica Ibero-Latinoamericana

versión On-line ISSN 1989-2055versión impresa ISSN 0376-7892

Cir. plást. iberolatinoam. vol.48 no.3 Madrid jul./sep. 2022 Epub 30-Ene-2023

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/s0376-78922022000300003

AESTHETIC

Predicting variables and preventing suboptimal results in face and neck surgical rejuvenation: a systematic physical and ultrasound evaluation

*Plastic Surgeon, Department of Plastic Surgery, UpClinic Surgery and Aesthetics, Lisbon, Portugal

Background and objective.

The evolution of surgical techniques for facial and neck rejuvenation has been significant over the last years. The choice of technique must be personalized according to the patient's anatomical details and specificities to provide individual and personalized results.

This work aims to expose our systematic preoperative evaluation of the patients that will be submitted to a face and neck surgical

Methods.

We present our preoperative evaluation checklist (subdi¬vided into 9 steps) to recognize the individual anatomical variants and deformities.

Using the physical exam and ultrasound evaluation of the face and neck we predict some variables that can make surgery more predictable and standardized. To do so we apply our 7 steps of pre-operative Decision Making Diagram of Face and Neck Rejuvenation Surgery.

Results.

Fifty-nine patients were submitted to face and neck lift between January 2019 and June 2021 using deep plane cervico-facial techniques according to our decision-making diagram. We demonstrate 2 clinical cases.

Conclusions.

In this paper, we explain why different surgical tech¬niques should be offered to different patients considering their individual needs. Using this checklist and decision-making diagram the surgeon will be able to make individualized decisions before surgery, such as SMAS flap lift vector direction, the type of the platysma treatment or the need for deep platysmal structures approach and treatment.

This work aims to reduce the likelihood of obtaining less satisfactory results by decreasing surgical errors and making the surgery faster.

Keywords Neck; Face; Rejuvenation; Preoperative evaluation; Ecography

Introduction

Skoog et al. were the first to describe platysma and skin dissection as a single unit in 1974, and Mitz and Peyronie described the SMAS in 1976.(1,2) Since then, increasing knowledge of the face anatomy allowed the significant evolution of surgical techniques of facial rejuvenation over the years.

Another important landmark to understand facial aging was the description of the facial fat compartments and their individualized evolution with the aging process.(3,4) Patients who ask for facelift surgery usually present ptosis of the superficial layers of the skin, in addition to deep fat face compartments atrophy and facial bone resorption.(5-8) Currently, performing face lipofilling simultaneously with facelifting is universally accepted as the gold standard treatment for facial rejuvenation. Face lipofilling improves skin quality and also allows refilling of the atrophied deep fat face compartments.(3,4,9-11)

It´s inappropriate to evaluate the aging face without evaluating the aging neck because their development occurs simultaneously. Different techniques can be used to achieve outstanding results in face and neck rejuvenation. In our experience, deep plane techniques allow the reposition of the different layers of the face that are crucial to achieving long-lasting results, better scars due to less tension on the skin, and more natural results. The facelifting technique we use consists of dissection and lifting of the mobile portion of the SMAS and is done according to the deep plane technique described by Hamra and posteriorly revisioned by Jacono.(12,13) The neck technique consists of the treatment of the neck structures that are superficial and deep to the platysma muscle, and also repositioning the plastyma muscle itself according to several principles described by different authors.(13-16)

According to Mendelson et al., the SMAS is the third layer of facial tissues of the face and continues in the neck as the platysma muscle.(17) It’s crucial to understand its implications during face and neck lifting procedures. When a SMAS flap is created and then lifted during a deep plane facelift, forces are created at the third layer of the cervicofacial tissues that are opposite to the forces created by the anterior platysmal plication during the neck lift. Jacono et al demonstrate very well these phenomena in cadavers.(18)

Subplatysmal fat, digastric muscles, and submaxillary glands can contribute to suboptimal neck definition. With this being considered, their pre-op evaluation must be performed to understand if they need to be treated, more accurate as possible.(14-16)

Whenever a cervicofacial surgical rejuvenation is performed, we are faced with intraoperative questions that are difficult to answer, such as “should a SMAS lift be performed using an oblique or horizontal vector orientation?” or “should a corset platysma muscle plication be sacrificed when the patient needs a greater oblique SMAS lift simultaneously?” or “Do the deep cervical structures need treatment?”

Objective and systematic preoperative evaluations are essential for the achievement and consolidation of the best surgical results.(19) The main aim of this work is to explain our systematized preoperative evaluation for cervicofacial surgery rejuvenation using the physical and ultrasound examination, and its relevance to take very important surgical decisions pre and intraoperatively.

Methods

Our systematic checklist of Preoperative Clinical Evaluation of the Face and Neck aims to standardize our clinical evaluation to recognize all individual anatomical variants and deformities. Using this detailed evaluation we can predict and control a greater number of variables during surgery. Fifty-nine patients were submitted to face and neck lift between January 2019 and June 2021 using deep plane techniques. All the patients have been studied preoperatively using The Preoperative Clinical Evaluation of the Face and Neck. The surgeries have been done by the same surgical team, namely by the senior author and helped by the first author.

The Preoperative Clinical Evaluation of the Face and Neck is subdivided into nine steps: 1) depth of nasolabial sulcus; 2) deformity of the jowl fat compartment; 3) face width; 4) chin position; 5) cervicomental angle; 6) platysmal laxity; 7) platysmal band position and activity; 8) subcutaneous and deep cervical fat; 9) submaxillary glands and/or digastric muscles hypertrophy (Fig. 1). This evaluation is performed using physical and ultrasound examinations.

In the first two steps, we evaluate the nasolabial and the jowl superficial fat compartments. The nasolabial fold and jowl must be evaluated according to its depth and deformation respectively as described in Fig. 2 and 3. The worsening of this characteristics translates into more aged faces. It should be noted that dental arches can negatively influence these aspects, which were not adressed in this evaluation.

Figure 2 and 3. This clinical case shows a deep nasolabial fold with an indication to perform facelift surgery. A moderate to a deep wrinkle in the nasolabial fold indicates an aging face.

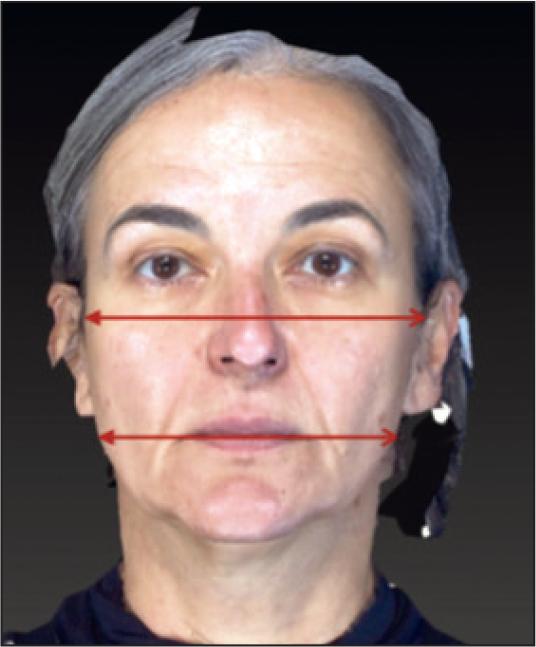

The third step is the evaluation of face width. The relative measurement of the width of the two lowers thirds of the face provides information about facial aging, which is essential to choosing the surgical technique. The width of the lowers two-thirds of the face is defined by the bizygomatic and bigonial distances, and then a relative comparison should be made between these two values (Fig. 4). Using these relative comparisons we classify an aging face as round when the middle third of the face is still wider than the inferior third, and squared when the inferior third of the face has approximately the same width as the middle third.

Figure 4. This clinical case shows a squared face with an indication to perform a facelift with an oblique orientation of the SMAS flap. The width of the lowers two-thirds of the face is defined by the bizygomatic and bigonial distances, and then a relative comparison should be made between these two values. Using these relative comparisons we classify an aging face as round when the middle third of the face is still wider than the inferior third and squared when the inferior third of the face has approximately the same width as the middle third.

The fourth step is the chin position. We consider that the ideal position of the chin in relation with the virtual plane of the vertical nose-lip line, which is defined by a vertical line that passes through the midpoint of the ideal length of the nose and the anterior projection of the upper and lower lips (figure 5). In this way, if the chin is retreated, normal, or protruded in relation with the vertical nose-lip line, we must classify the chin as retrognathic, normal, or prognathous, respectively.

Figure 5. This clinical case shows a normal chin position. The chin is retreated, normal, or protruded according to its position in relation with the vertical nose-lip line plane, which is defined by a vertical line that passes through the midpoint of the ideal length of the nose and the anterior projection of the upper and lower lips.

The fifth step is the cervicomental angle. This angle is defined between chin, hyoid, and thyroid cartilage (Fig. 6). An angle with a value greater than 120º can be present in an aging neck with loss of definition, and in turn, a value of less than 105º can be observed in the skeletonized neck secondary to a prior neck lift surgery. Thus, we must classify it as: <105º; > 105º and <120º; > 120º.(20)

Figure 6. This clinical case shows a cervicomental angle with more than 120º with loss of definition and with indication to perform a neck lift. The cervicomental angle is defined between chin, hyoid, and thyroid cartilage.

The sixth step is the platysmal laxity and anterior platysma diastasis. Platysmal laxity can be evaluated through a finger-assisted maneuver during the physical examination and the anterior platysma muscle diastasis through ultrasound evaluation. The finger-assisted maneuver is a test in which three fingers (second, third and fourth fingers) are placed vertically along one line that is defined between the jaw angle and the external canthus bilaterally. Then the surgeon should make a movement that mimics a vertical facelift vector by pulling the skin, SMAS, and platysma muscle. If correction of the platysmal submental laxity with this movement is not verified with this maneuver, we classify it as a severe platysma muscle laxity.(18) Using the ultrasound evaluation (Toshiba Xario XG) (camera positioned in the midline and three centimeters below the chin) it is possible to quantify the distance between the anterior borders of the platysma muscle (Fig. 7). The platysmal laxity is classified as present or absence. The anterior platysma diastasis is quantified in millimeters.

Figure 7. This clinical case shows a severe platysma muscle laxity with the distance between the two anterior borders of the platysma muscle bigger than 20 millimeters by ultrasound evaluation, and with indication to perform a simple or a corset anterior platysma plication. We evaluate platysmal laxity through and the anterior platysma muscle diastasis through ultrasound evaluation. Using the ultrasound evaluation (camera positioned in the midline and three centimeters below the chin) it is possible to quantify the distance between the anterior borders of the platysma muscle.

The seventh step is the evaluation of platysma bands position and activity. This is done by inspection during physical examination. The platysma muscle should be evaluated at rest and during muscle activity, to determine the platysma bands presence, location, and activity (Fig. 8). We classify them as “present” or “absent”, “medial” or “lateral” and as “active” or “inactive”, respectively.

Figure 8. This clinical case shows the presence of lateral and medial active platysma bands with indication to perform medial and lateral platysmotomies, or complete platysmotomies. During the physical exam, the evaluation of the platysma muscle must be done at rest and during muscle activity, to evaluate the platysma bands presence, location, and activity.

The eighth step is the subcutaneous and deep cervical fat evaluation, which should be assessed on physical examination by palpation and by ultrasound evaluation (Fig. 9). The physical evaluation is made using the following maneuver described by Meija et al.: trap the submental fat between the first and second fingers of the hand and then ask the patient to stimulate the platysma muscle. The fat that remains immobile between the fingers after platysma muscle movement is subcutaneous fat, the remaining mobile fat is deep cervical fat.(21) Despite the subcutaneous and deep cervical fat evaluation present a low sensitivity and specificity to distinguish one from each other, this information is useful to check the presence of the total fat volume. When an excess of total cervical volume is present during the physical examination, ultrasound evaluation can be used to quantify the thickness (in millimeters) of the subcutaneous fat that is located superficially to the superficial cervical fascia and to quantify the deep cervical fat (in millimeters) that is located deeply to the superficial cervical fascia in between the two anterior bellies of the digastric muscles.

Figure 9. This clinical case shows a deep cervical fat thickness and subcutaneous fat thickness bigger than 5 millimeters by ultrasound evaluation, and with indication to perform an open lipectomy. We evaluate deep cervical fat excess and subcutaneous fat excess through ultrasound evaluation. Using the ultrasound evaluation (camera positioned in the midline and three centimeters below the chin) it is possible to quantify the thickness of these layers.

The ninth step is the submaxillary glands and/or digastric muscles evaluation. Submaxillary gland hypertrophy and digastric muscle hypertrophy examination by inspection have very low sensitivity and for this reason, we prefer to use ultrasound evaluation. This way we can quantify (in millimeters) the distance between the two anterior bellies of the digastric muscles, the biggest diameter of each anterior belly of the digastric muscle, and the biggest diameter of each submaxillary gland (Fig. 10-12).

Figures 10 and 11. This clinical case shows digastric muscles with its biggest diameters superior to 10 millimeters with indication to perform a partial digastric miectomy, and also a distance between the two anterior bellies of the digastric muscles bigger than 10 millimeters with indication to perform its plication. Using the ultrasound evaluation (camera positioned in the midline and three centimeters below the chin) is possible to quantify (in millimeters) the biggest diameter of the digastric muscle, and to quantify (in millimeters) the distance between the two anterior bellies of the digastric muscles.

Figure 12. This clinical case shows hypertrophy of the submaxillary gland with its biggest diameters superior to 25 millimeters with an indication to perform its partial excision. Using the ultrasound evaluation (camera positioned three centimeters below the level of the body of the mandible bilaterally) is possible to quantify (in millimeters) the biggest diameter of the submaxillary gland.

After a complete face and neck examination, face and neck surgery planning takes place.

Using the measurements of the pre-operative evaluation the seven steps Decision Making Diagram will guide the surgeon/our decision process (Fig. 13):

Step 1 - Does the patient need facelift surgery?

To answer this question we use the first two steps of the pre-operative examination. The aging process increases the nasolabial sulcus depth and creates a marked deformation at the lateral edge of the labial commissure along the mandibular line known as jowl deformation. This phenomenon occurs because the nasolabial and jowl fat compartments maintain their volume during the aging process, in contrast to the lipoatrophy and reduction of the volume verified in the other facial medial fat compartments. The maintenance of the nasolabial and jowl fat compartments volume results in a relative increase in contrast to adjacent facial fat compartments. Furthermore, during the aging process, there is an increase in the laxity of the ligaments that support the superficial fat compartments of the face. This increased ligament laxity associated with the maintenance of the nasolabial and jowl fat compartments results in a very marked nasolabial sulcus and a jowl deformation.(3,9) When a patient has a marked jowl deformation and/or a deep nasolabial sulcus depth, we consider that this patient has significant facial ptosis in association with lipoatrophy of medial fat compartments of the face. If any of these situations are verified we consider that the patient needs a facelift with simultaneous lipofilling of the deep medial fat compartments.

Step 2 - If the patient needs a facelift, is a chin treatment necessary?

If the chin bone support is not ideal the facelift result can be suboptimal. For this reason, when a patient has a retrognathic chin in a sagittal view, we perform a chin augmentation with implant or lipofilling.

Step 3 - If the patient needs a facelift, how far should the SMAS dissection go, which SMAS lift vector should be chosen, and should a smasectomy of the non-mobile segment of the SMAS be performed?

The quantification and relative comparison between the width of the two inferior thirds of the face provides essential information about facial aging and facelift surgery decisions.

We must adapt the different lifting vectors of the SMAS flap and the degree of SMAS flap undermining to the different facial shapes. It is important to understand that, if a facelift with a major undermining of the SMAS (extensive dissection of the SMAS beyond the zygomatic ligament) is done and an oblique vector to lift the SMAS (a vector that is oblique to the interpupillary line) is applied, we’re able to perform an obliquely oriented lift, from medial to lateral, of all the medial structures of the face, widening the middle third of the face. On the other hand, If a facelift with a minor undermining of the SMAS (minor dissection of the SMAS medially to the zygomatic ligament) is done and a horizontal lift vector of the SMAS (a vector that is parallel to the interpupillary line) is applied, we’re able to perform a horizontal oriented lift, from medial to lateral, with a lower ability to lift the medial structures of the face compared with the major undermining technique, narrowing the middle third of the face.(22)

It should be noted that oblique mobilization of the SMAS flap can also be used in patients who simultaneously need periocular rejuvenation, especially in those with a significant lower eyelid height and a marked malar-palpebral crease, regardless the shape of the face.

When presented with a patient with a round face, this means a wider middle third of the face compared to the inferior third, and for that reason a facelift with less undermining of the SMAS and with a horizontal vector for SMAS lift must be considered, to lift the lower two-thirds of the face without creating a wider middle third of the face and at the same time preserving the malar tissues that are well-positioned and not deflated. When a horizontal SMAS vector in a facelift is used, the tissues of the submalar region of the middle third of the face are lifted causing the improvement of the malar/submalar relation and transition. The lower third of the face including the jowl deformity is also treated. Furthermore, in round faces, we perform smasectomy of a portion of the non-mobile SMAS (Fig. 14) to reduce the lateral volume and consequently to reduce the width of the middle face.

Differently, when presented with a patient with a squared face, that means that the width of the middle third of the face is similar or narrow compared to the inferior third of the face, a facelift with the major undermining of the SMAS and with an oblique vector for SMAS lift must be considered. In this situation we must treat the two lowers thirds of the face with the concern to create a middle third of the face wider than the lower third. We release all the face ligaments including the zygomatic, masseteric and mandibular ligaments and lift the two lower thirds of the face by recruiting the superficial fat compartments from a medial and inferior to a more lateral and superior part of the face using an oblique vector. This allows us to widen the middle third of the face and reshape the proportions to a more youthful appearance. Its clinical endpoint is reached when canine teeth are exposed during the superomedial mobilization of the middle third of the face and consequent mobilization of the upper lip, as recommended by Timothy Marten.

Step 4 - Does the patient need neck lift surgery?

During the aging process of the neck, the cervicomental angle tends to be less defined causing an unpleasant aesthetic configuration of the neck according to the youthful cervical appearance described by Ellenbogen.(20) When this angle value is greater than 120º a neck lift must be considered.

Step 5 - If the patient needs a neck lift, should a subplatysmal approach be used?

When planning a neck lift the surgical incisions must be planned. The lateral approach to the neck is used in continuity with the retro auricular incision of the facelift, we recommend that its incision should be 2 millimeters lateral and parallel to the capillary line and not intracapillary, due to risk of deformation. The submental approach is additionally used when we need to treat a neck with significant platysma muscle laxity, medial platysma bands or to treat the subplatysmal structures.

Using the sixth, seventh, eighth and ninth steps of the physical examination we can predict the patients that will need a submental approach.

Patients with severe anterior platysma diastasis, benefit from an anterior platysma plication to improve its redundancy. The anterior plication can create an anterior submental bulking with less cervical definition, which can be avoided by treating the submental structures simultaneously.

Patients with a severe platysma muscle laxity at physical evaluation and/or if the distance between the two anterior borders of the platysma muscle is bigger than twenty millimeters by ultrasound evaluation must undergo a simple or a corset anterior platysma plication. Patients with subplatysmal fat excess, hypertrophy of submaxillary glands, and/or digastric muscle hypertrophy should also be considered as candidates for subplatysmal treatment by submental approach. In this way, using the ultrasound evaluation (eighth step of the pre-operative evaluation), we classify a subcutaneous fat layer excess when this layer is thicker than 5 millimeters. In these situations, we must consider their open lipectomy (or neck liposuction when the anterior platysma plication and or treatment of the deep structures are not needed). It´s also important to evaluate the deep cervical fat excess when this layer is thicker than 5 millimeters, and its open lipectomy must be considered. When ultrasound evaluation shows a distance between the two anterior bellies of the digastric muscles bigger than 10 millimeters we must considerer its plication. A diameter of the anterior belly of the digastric muscle bigger than 10 millimeters is associated with muscle hypertrophy in our experience, and its partial miectomy must be considered. A diameter bigger than 25 millimeters of the submaxillary gland is associated with submaxillary gland hypertrophy and its partial excision must be considered. This deep approach must be carried out judiciously, to avoid the deformation known as “cobra neck deformity”. Subplatysmal interdigastric lipectomy must be performed with care, and in our opinion, the treatment of the various subplatysmal structures together is very important.

Step 6 - Does the patient have active platysma bands? Medial, lateral, or both?

If we confirm the presence of active platysma bands during the physical examination we may considerer performing medial and/or lateral platysmotomies, or complete platysmotomies.

Step 7 - If the patient needs a facelift and neck lift simultaneously, what kind of anterior platysma treatment (simple anterior platysma plication, corset anterior platysma plication, or no anterior platysma plication) should be performed?

The anterior pulling maneuver by anterior platysma muscle plication can create some limitations to the SMAS dissection as well as its oblique lift and fixation. These limitations were well described by Jacono et al, who also explain that these limitations are significantly higher when using the SMAS oblique lift in comparison with the limitations imposed by the SMAS horizontal lift.(16)

In these patients, we must establish their clinical priorities. So based on steps three and five of the decision-making diagram we divide the patients into three different groups.

The first group is composed of patients who need a SMAS oblique vector facelift without anterior platysma plication and/or subplatysmal structures treatment. In this group, a facelift with SMAS dissection and fixation should be performed, and also perform the neck lift without the submental approach.

The second group is composed of patients that need a SMAS oblique vector facelift with a simultaneous need of anterior platysma plication and/or treatment of the subplatysmal structures. In this group we should start with the SMAS dissection and fixation to treat the deep face structures without any limitations. Then, we must proceed to the deep structures approach associated with a simple anterior platysma plication.

The third group is composed of patients that need an anterior platysma plication and/or subplatysmal structures not needing a SMAS oblique vector facelift. In this group of patients, the SMAS fixation is not a limitation, so we should treat the subplatysmal structures and perform a corset platysma plication according to the severity of the platysma laxity.

Results

This systematic checklist of Preoperative Clinical Evaluation of the Face and Neck allowed us to diagnose and treat each patient individually. It proved to be essential to identify the most appropriate SMAS vector for each patient and became able to identify the need of treatment of the deep cervical structures.

We show two clinical cases demonstrating the relevance of this systematic approach.

In the first clinical case, the patient had a squared face, a deep nasolabial sulcus with a severe jowl deformity. Additionally, she had a heavy neck with a cervicomental angle bigger than 120º, with severe platysma laxity, a severe platysma diastasis, subplatysmal fat excess, hypertrophy of the submaxillary glands and hypertrophy of the digastric muscles (Fig. 15 and 16). According to her physical and ultrasound evaluations and using the decision-making diagram, we firstly performed lipofilling of the deep medial fat compartments using 25cc of fat harvest from the abdomen (fat was collected manually with a 0,8mm cannula (SEFFI) and centrifuged at 1000G during 3 minutes. Fat was infiltrated with 0,7 and 0,9 cannulas (FAGGA)). Secondly proceeded with the deep plane facelift with an oblique vector and greater undermining of the SMAS. Followed the neck lift with resection of the subcutaneous fat, followed by treatment of the subplatysmal structures, including partial resection of the submaxillary glands, resection of subplatysmal fat, partial resection of the anterior belly of the digastric muscles and its anterior plication and finally, anterior corset plication of the platysma muscle and lateral fixation of the platysma muscle to the mastoid (Fig. 18).

Figure 15. Clinical Case 1 (pre and post operation comparison with a complete rejuvenation of face and neck - frontal view).

Figure 16. Clinical Case 1 (pre and post operation comparison with a complete rejuvenation of face and neck - lateral view and lateral view with neck flexion).

Figure 17. Clinical Case 2 (deep plane facelift surgery with the greater undermining of the SMAS including the release of the zygomatic ligament and lipofilling of the deep medial fat compartments).

Figure 18. Clinical Case 1 (deep plane neck lift surgery with: partial excision of the anterior bellies of the digastric muscles, partial excision of the submaxillary glands, excision of the deep cervical fat and corset anterior plication of anterior borders of the platysma muscle).

In the second clinical case, the patient had a squared face, a moderate nasolabial sulcus with a moderate jowl deformity. Additionally, she had lost the mandible contour associated with platysma laxity, and submentonian volume excess due to a subplatysmal fat excess, hypertrophy of the submaxillary glands and hypertrophy of the digastric muscles (Fig. 17,19 and 20). According to her physical and ultrasound evaluations and using the decision-making diagram, we firstly performed lipofilling of the deep medial fat compartments using 35 cc of fat harvest from the abdomen, followed by facelift and necklift according to the technique described in clinical case 1 (Fig. 21).

Figure 19. Clinical Case 2 (pre and post operation comparison with a complete rejuvenation of face and neck - frontal view).

Figure 20. Clinical Case 2 (pre and post operation comparison with a complete rejuvenation of face and neck - lateral view and lateral view with neck flexion).

Discussion

Many studies have proven good surgical results of facelifts using less invasive techniques, such as smasectomy with plication or SMAS imbrications.(8,19,24) Extensive subcutaneous dissections may be associated with complications such as flap necrosis. Techniques that undermine and lift the SMAS layer have the great advantage of lifting a larger amount of skin without tension and also achieving more natural and long-lasting results. These techniques, allow the lifting repositioning of the SMAS, superficial fat compartments, and skin as a compound unit, providing the same amount or better of subcutaneous lift with less subcutaneous tissue undermining.(12,13,25,26)

Facial rejuvenation has been evolving over the past few decades, and the concept of facial lifting was replaced by the new concept of facial reshaping.(7) It means that proper facial rejuvenation requires a general assessment of the face, not only in terms of facial ptosis, but also face volume deflation due to bone reabsorption and lipoatrophy of the face compartments. We consider that lipofilling of the piriformis region, nasolacrimal sulcus, chin, nasolabial sulcus, deep submalar, and marionette region must be done in all the patients that present a deflated medial cheek signalized by the jowl deformation and severe nasolabial sulcus. To offer greater and longer surgical results to our patients, we believe that in selective cases facelift surgery should be done using a SMAS flap in combination with lipofilling of the deep medial fat compartments.

The deep plane facelift technique allows the repositioning of ptotic structures that are superficial to the SMAS including the superficial fat compartments and the skin. Using this technique it’s possible to achieve natural results avoiding the excessive forces in the skin flap. However, with the deep plane technique, one should not use the same direction of SMAS flap mobilization in all the patients. Is crucial to evaluate the width relationship between the two inferior thirds of the face to maximize the results. To correct a squared face we will need to do a major undermining of the SMAS flap (beyond the zygomatic ligament) to reposition the superficial fat compartments to their original position using an oblique vector. On the other hand, to correct a round face we limit our SMAS undermining and the lift is made in a horizontal vector in association with a smasectomy of the non-mobile portion of the SMAS.(22)

Like the facelift, the necklift or neck reshaping techniques have also evolved. Neck treatment using only liposuction does not treat tissue laxity, increases the risk of superficial deformations, and evidentiary the aging of underlying structures.(14) Different techniques are available, but not all should be applied to all patients. It is important to make a correct preoperative assessment to understand and decide when a patient benefits from a more invasive approach, with manipulation of the submaxillary glands, digastric muscles, and subplatysmal fat or when the patients only need platysma manipulation.(14,16) The subplatysmal structures treatment is not free of complications, being described in the literature the occurrence of as sialoma, hematoma, nerve damage, dry mouth, or iatrogenic deformation.(27) In our experience we verify, we found only a low incidence of contour irregularities and temporary paresis.

The SMAS is in continuity with the platysma muscle and for this reason, the treatment of the anterior borders of the platysma muscle must be adapted according to the specific needs of the patient.

When is needed an anterior platysma treatment, the corset anterior platysma plication is the better technique to define the neck midline contour.(23,28) However, this technique cannot be used if the SMAS flap lift has an oblique vector direction. In this situation, it is replaced by a simple anterior platysma plication, except in cases of severe platysma laxity.

Suboptimal neck lift surgery results can be avoided by the treatment of the subplatysmal structures.(14,16) Despite the low sensitivity and specificity of the neck physical examination, it can identify some patients that benefit from a more advanced approach through a submental incision. The sensitivity of ultrasound neck evaluation seems to be higher. Nowadays we use this technology in every pre-operative evaluation as it proves to be very useful for surgical planning. Deformations as “cobra deformity” or other irregularities can occur if some subplatysmal structures are poorly adressed, especially the interdigastric fat. We considerer that the submental approach should be done in the presence of significant platysmal muscle laxity evaluated by the physical exam, subplatysmal fat excess, hypertrophy of the submaxillary gland, hypertrophy of the digastric muscles and marked platysmal muscle diastasis diagnosed through ultrasound evaluation.

Face and neck lift surgery are very demanding and require detailed planning and a personalized pre-operative evaluation.

This work aims to optimize the decision-making process before and during surgery, to allow the surgeon to focus on his surgical expertise, and to reduce total surgery time.

Using this preoperative evaluation and decision-making diagram you will be able to avoid less favorable results by identifying the need for retrognathism correction, the correct degree of SMAS undermining, the correct direction of the SMAS vector pulling, as well as the cases that benefit from deep platysma structures treatment and the correct type of anterior platysma plication (Fig. 13).

Conclusions

The emergence of social networks has triggered an increasing demand for facial surgical treatments. Patients want more natural results without surgical stigmas. Preoperative planning has taken a fundamental role in enhancing surgical results in face and neck surgeries.

In this work, we present our preoperative approach that takes into account different anatomical details of the physical and ultrasound examinations of the face and neck. We recommend the use of this working method in all face and neck surgeries, as it offers the possibility of preoperatively recognizing the degree of SMAS dissection, the vector orientation of SMAS fixation, and the deep structures of the neck need of treatment, providing and optimization of surgical results with a decreased number of surgical errors, as also with a reduction in the total surgical time.

As future perspectives, it will be interesting to predict and evaluate the exact orientations of the SMAS fixation points as well as the exact volumes to be excised from the subplatysmal structures.

Disclosures: The authors have no financial disclosures.

REFERENCES

1. Skoog, T., 1974. Plastic surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders. [ Links ]

2. Mitz, V. and Peyronie, M., The Superficial Musculo-aponeurotic System (SMAS) in the parotid gland and cheek area. Plast. Rec. Surg 1976; 58(1):80-88. [ Links ]

3. Rohrich, R. and Pessa, J., The Fat Compartments of the Face: Anatomy and Clinical Implications for Cosmetic Surgery. Plast. Rec. Surg. 2007;119(7):2219-2227. [ Links ]

4. Rohrich, R., Ghavami, A., Constantine, F., Unger, J. and Mojallal, A., Lift-and-Fill Face Lift. Plast. Rec. Surg, 2014;133(6):756e-767e. [ Links ]

5. Lambros, V., Models of Facial Aging and Implications for Treatment. Clinics in Plast. Surg, 2008;35(3):319-327. [ Links ]

6. Gierloff, M., Stöhring, C., Buder, T., Gassling, V., Açil, Y. and Wiltfang, J. Aging Changes of the Midfacial Fat Compartments. Plast. Rec. Surg 2012:129(1):263-273. [ Links ]

7. Stuzin, J. Restoring Facial Shape in Face Lifting: The Role of Skeletal Support in Facial Analysis and Midface Soft-Tissue Repositioning. Plast. Rec. Surg, 2007;119(1):362-376. [ Links ]

8. Warren, R., Aston, S. and Mendelson, B., Face Lift. Plast. Rec. Surg. 2011;128(6):747e-764e. [ Links ]

9. Stuzin, J., Rohrich, R. and Dayan, E. The Facial Fat Compartments Revisited. Plast. Rec. Surg, 2019;44(5):1070-1078. [ Links ]

10. Tonnard, P., Verpaele, A., Peeters, G., Hamdi, M., Cornelissen, M., & Declercq, H. Nanofat Grafting. Plast Reconst Surg, 2013;32(4):1017-1026 [ Links ]

11. Atiyeh, B., Ghieh, F., & Oneisi, A. Nanofat Cell-Mediated Anti-Aging Therapy: Evidence-Based Analysis of Efficacy and an Update of Stem Cell Facelift. Aesth Plast Surg, 2021;45(6):2939-2947 [ Links ]

12. Hamra, S. The Deep-Plane Rhytidectomy. Plast Reconst Surg, 1990:86(1):53-61. [ Links ]

13. Jacono, A. and Bryant, L. Extended Deep Plane Facelift. Clin in Plast Surg, 2018;5(4):527-554. [ Links ]

14. Marten, T. and Elyassnia, D. Neck Lift. Clin in Plast Surg, 2018;5(4):455-484. [ Links ]

15. Marten, T. and Elyassnia, D. Management of the Platysma in Neck Lift. Clin in Plast Surg 2018;5(4):555-570. [ Links ]

16. Auersvald, A. and Auersvald, L. Management of the Submandibular Gland in Neck Lifts. Clin in Plast Surg 2018;45(4):507-525. [ Links ]

17. Mendelson, B. and Jacobson, S. Surgical Anatomy of the Midcheek: Facial Layers, Spaces, and the Midcheek Segments. Clin in Plast Surg, 2008;35(3):395-404. [ Links ]

18. Jacono, A. A. The Effect of Midline Corset Platysmaplasty on Degree of Face-lift Flap Elevation During Concomitant Deep-Plane Face-lift A Cadaveric Study. JAMA Facial Plast Surg, 2016:E1-E5. [ Links ]

19. Rohrich, R.J. The Individualized Component Face Lift: Developing a Systematic Approach to Facial Rejuvenation. Plast Reconst Surg,2008:1050-1063. [ Links ]

20. Ellenbogen, R., & Karlin, J. Visual Criteria for Success in Restoring the Youthful Neck. Plast Reconst Surg 1980;66(6):826-837. [ Links ]

21. Mejia, J., Nahai, F., Nahai, F., & Momoh, A. Isolated Management of the Aging Neck. Sems in Plast Surg, 2009;23(4):264-273 [ Links ]

22. Stuzin, J. Restoring Facial Shape in Face Lifting: The Role of Skeletal Support in Facial Analysis and Midface Soft-Tissue Repositioning. Plast Reconst Surg,2007;119(1):362-376. [ Links ]

23. Feldman, J. Corset Platysmaplasty. Plast Reconst Surg, 1990;85(3):333-343. [ Links ]

24. Baker, D. Minimal incision rhytidectomy (short scar face lift) with lateral SMASectomy. Aesth Surg J, 2001;21(1):68-79. [ Links ]

25. Barton, F. The "high SMAS" face lift technique Aesth Surg J. 2002;22(5):481-486. [ Links ]

26. Marten, T. High SMAS Facelift: Combined Single Flap Lifting of the Jawline, Cheek, and Midface. Clin in Plast Surg, 2008;35(4):569-603. [ Links ]

27. Auersvald, A., & Auersvald, L. Innovative Tactic in Submandibular Salivary Gland Partial Resection. Plast Reconst Surg GO,2014; 2(12):e274. [ Links ]

28. Labbé, D., & Giot, J. Open Neck Contouring, Clin in Plast Surg 2014; 41(1):57-63 [ Links ]

Received: February 08, 2022; Accepted: August 02, 2022

texto en

texto en