My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Medicina y Seguridad del Trabajo

On-line version ISSN 1989-7790Print version ISSN 0465-546X

Med. segur. trab. vol.61 n.239 Madrid Apr./Jun. 2015

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0465-546X2015000200009

REVISIONES

Attitudes toward the risk prevention in health professionals in cases of epidemiological alert

Actitudes hacia la prevención de riesgos laborales en profesionales sanitarios en situaciones de alerta epidemiológica

Belén Collado Hernández1-3, Yolanda Torre Rugarcía2-3

1. Mutua Montañesa de Cantabria. Spain.

2. Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla. Spain.

3. Teaching Unit of Occupational Health of Comunidad de Madrid. Madrid. Spain

This work has been carried out as part of the Scientific Program of the National School of Occupational Medicine of the Carlos III Health Institute under an agreement with the Teaching Unit of Occupational Medicine of the Community of Madrid, Spain.

ABSTRACT

Objectives: To explore the scientific evidence regarding the behavior of health professionals in pandemic situations. Identify areas of improvement for the strengthening of health professionals before pandemic situations. Secondary Objectives: To identify the psychosocial impact, adoption and adherence to preventive measures and vaccination programs.

Methods: Systematic review of the scientific literature collected in the MEDLINE (PubMed), Scopus and Cochrane Library Plus data until December 2014. The terms used as descriptors were: "Disease Outbreaks", "Coronavirus, sars", "Severe acute Respiratory Syndrome", "Influenza virus, subtype H1N2", "Health occupations", "Emergencies, Infectious disease transmission", "patient-to-professional", "Infectious disease transmission, professional-to-patient".

Results: 181 references after the elimination of duplicates and application of the criteria for inclusion and exclusion and analysis of quality using the STROBE criteria, was a final collection of 17 articles were retrieved. The level of evidence found according to Sign Criteria is three as it is in all cases of cross-sectional studies. 11 Authors refer to psychosocial effects, 3-vaccination and 12 to adherence to preventive measures. In general preventive measures in the two pandemics were well appreciated and followed by professionals. A significant burden of stress for fear of getting sick is generated; infect their families and high workload. Low adherence to vaccination programs and use of scientific literature.

Conclusions: It would be advisable to improve communication about preventive measures in times of pandemic to increase adherence and psychological support to health workers.

Key words: Disease outbreaks, Coronavirus, SARS, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Influenza a virus, H1N2 subtype, Health occupations.

RESUMEN

Objetivos: Conocer la evidencia científica existente en relación al comportamiento de los profesionales de la salud en situaciones de pandemia. Identificar puntos de mejora para el fortalecimiento de los profesionales sanitarios antes situaciones de pandemia. Objetivos secundarios: Identificar el impacto psicosocial, adopción y adhesión a medidas preventivas y a programas de vacunación.

Métodos: Revisión sistemática de la literatura científica recogida en las bases de datos MEDLINE (Pubmed), SCOPUS y Cochrane Library Plus hasta Diciembre de 2014. Los términos más utilizados como descriptores fueron: "Disease outbreaks", "Coronavirus, sars", "Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome", "Influenza a virus, h1n2 subtype", "Health occupations", "Emergencies, Infectious disease transmission", "patient-to-professional", "Infectious disease transmission, professional-to-patient".

Resultados: Se recuperaron 181 referencias que tras la eliminación de duplicados y aplicación de los criterios de inclusión y exclusión y análisis de calidad mediante los criterios STROBE, resultó una colección final de 17 artículos. El nivel de evidencia encontrado según los Criterios Sign es tres ya que se trata en todos los casos de estudios transversales. 11 autores hacen referencia a efectos psicosociales, 3 a la vacunación y 12 a adhesión a medidas preventivas. En general las medidas preventivas en las dos pandemias fueron bien valoradas y seguidas por los profesionales. Se genera una importante carga de estrés por el miedo a enfermarse, contagiar a sus familias y la elevada carga laboral. Baja adherencia a programas de vacunación y a la utilización de literatura científica.

Conclusiones: Sería recomendable mejorar la comunicación sobre las medidas preventivas en periodos de pandemia para aumentar su adherencia así como dar apoyo psicológico al personal sanitario.

Palabras clave: Epidemia, Coronavirus, SARS, Síndrome respiratorio agudo severo; Virus de la gripe A subtipo H1N1, Personal sanitario.

Introduction

The latest global health alert the XXI century has been caused by the Ebola virus. It began in December 2013 in Guinea and later spread throughout West Africa. Currently there are 21,362 cases and 8,478 deaths worldwide (WHO 01/11/2015). The first contagion in Europe was declared in Spain in October 2014. It was a nursing assistant who had been in contact with the two missionaries repatriated. Two nurses were infected in the same way USA. This created a major social and health warning about the possible failure of preventive measures related mainly to medical staff and PPE used.

Two other pandemics were previously reported in this century, SARS and influenza A (H1N1). In relation to SARS, OMS²² said 8,098 cases between November 2002 and July 2003. Of these, 1,707(21 %) were health workers (Shapiro et al.10). Influenza A, in late September 2009, affected globally to over 343,298 with about 4,108 deaths (Alenzi et al.¹) with a high percentage of health workers affected.

In the case of swine flu (H1N1) measures established by the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention20) were: 1) Review and / or development of plans for pandemic prevention by health centers and report them to the staff. These in turn should receive training on disease prevention (vaccination, EPIS...) and the risk of complications. 2) Reduce potential exposures (limit transport patients, visitors...). 3) Physical controls such triage separate areas. 4) Promotion and provision of vaccine (free during work hours, refusal form fill where applicable). 5) Provide appropriate education PPE and use (N-95 masks, non-sterile gloves...). 6) Hand hygiene and respiratory hygiene. 7) Quarantine (up to 24 hours of disappearance of fever without antipyretics) mandatory for health workers should be monitored for signs/symptoms of the disease.

Referring to SARS were to follow the measures described above and also under the Protocol for Surveillance and Control of SARS (National Centre for Epidemiology Institute Salud²¹ Carlos III, May 2004.): 1) The quarantine will be up to 48 hours of cessation of fever. 2) negative pressure rooms if possible. 3) PPE: disposable hats, eye protection, gloves, disposable clothing (overalls/aprons/gowns), decontaminable boots. Respiratory protection is not reusable: surgical mask (protection issue) and respiratory protective devices (protection inhalation) that are certified according to European standard (EN 149: 2001 FFP2 and FFP3) and (UNE-EN 143: 2000 P2). In Spain the use of protective FFP2 (staff not caring for the patient) and FFP3 (direct patient contact) is recommended.

All these preventive measures can be in accordance with what difficult circumstances to perform. Not only because of the possibility of such negative pressure room or appropriate PPE if not acceptance or rejection thereof by the health workers could occur for example on the issue of vaccination that ultimately would be a decision staff.

The presence of a pandemic could bring psychosocial consequences among health workers related to concerns about the spread or the health of your family. All this can produce a significant stress load that could see increased if we consider that a significant volume of patients by the general alarm the population increase during epidemics.

The health sector is a high-risk group in pandemic situations. The aim of this paper is to review the literature to learn the scientific evidence regarding the behavior of health professionals in pandemic situations and identify areas of improvement for the strengthening of health professionals in these situations. As secondary objectives we have set out to identify the psychosocial impact, adoption and adherence to preventive measures and adherence to vaccination programs.

Material and methods

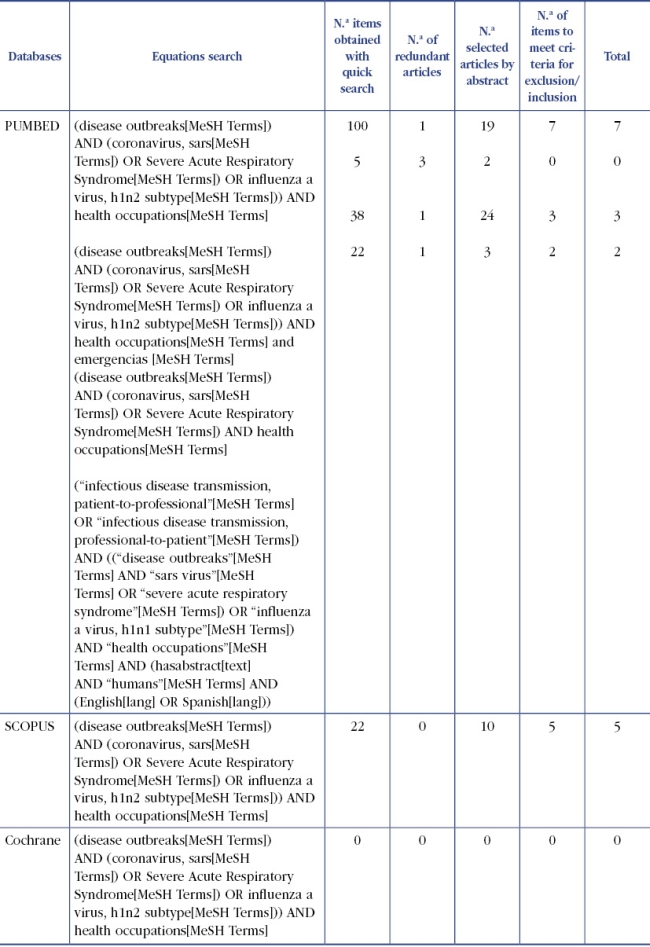

The study was conducted using techniques of systematic review of the literature obtained by direct contacts and access, via the Internet, available in three databases (Table 1), International Literature Medlars Online (MEDLINE ), via PubMed, Scopus and Cochrane Library Plus.

Table 1. Terms, equations and descriptors

To define the search terms MeSH terms (thesaurus developed by the US National Library of Medicine) were employed, using the descriptors listed in Table (Table 1) in text format in title and/or abstract.

With them different Boolean combinations are made finally obtaining three equations search (Table 2) in MEDLINE/PubM. The filters listed in the table (Table 1) were used. The same strategy was adapted to the characteristics of other databases consulted. The search was performed from the first available date, according to the characteristics of each database, until November 2014 (time of last update).

The final choice of articles was performed as meeting the inclusion criteria:

— Adapting to the objectives of the search.

— Population studies collected should be health workers.

— Provide summary.

— Ability to retrieve the full text of the paper.

— English or Spanish language.

Articles were excluded:

— Do not contributed empirical information regarding the effects of a health alert health professionals.

— Population studied different health sector.

— Editorials and review articles

— Duplicate publications, including in the analysis, in this case, the most complete study.

The selection of relevant articles was performed independently by two authors of this review.

To give as valid the inclusion of studies established that the valuation of the concordance between the two authors (Kappa index) should be one. The possible discrepancies between the two authors should be resolved by consensus between them.

To assess the quality of the articles selected for publication guidelines observational studies STROBE23 were used. Items are grouped, in order to systematize and facilitate the understanding of the results, according to the study variables, considering the variables listed in Table 3. In addition the SIGN criteria were used for the allocation of evidence for selected items.

Results

With the search criteria described a total of 187 references were collected, of which after applying the criteria of inclusion and exclusion reading the summary, and discard duplicates and non-refundable full text, 41 items are selected, of which full text after reading and analyzing their methodological quality according to the STROBE criteria are considered relevant 17. All works are from MEDLINE and SCOPUS not found publications that met the criteria for inclusion and exclusion in the Cochrane Library (Figure 1 and Table 4).

All the studies reviewed are treated cross-sectional studies, and therefore their level of evidence is 3 (SIGN) so to implement more quality to the results of the review it was decided to evaluate it, using the questionnaire STROBE23 (Table 5) to give a score ranging between 13.5 and 18.5, indicating that all items have good or excellent quality.

Table 5. STROBE of the articles included in the review

The study of Tan WM. et al.12 was presented smaller sample size (n = 90), whereas de Nickell LA. et al.6 work was larger l (n = 2001). In two of the 17 items the study population was purely medical. The study of Idrovo AJ. et al.3 included only medical students graduate and three studies the sample belonged entirely to nurses case of predominantly female population. (table 6, table 7, table 8, table 9).

Psychosocial impact

We found seven articles referring to stress, anxiety, and all elevated levels of both states are evident during the two pandemics, except Vinck L. et al.16 in a study conducted during the pandemic influenza A doctors, nurses and managers through voluntary questionnaires, finds that 60% does not show anxiety infected. Contrary to this LA Nickell obtained. et al.6 in a study conducted during the SARS pandemic in Toronto about psychosocial factors of health personnel. It notes that 64.7% showed concerned about your health. Additionally, we can add as Wong WCW. et al.18 also anxiety spread themselves, have high level of anxiety infect their families (p '0.01). LA Nickell. et al.6 identified four factors associated with increased concern for personal or family health: the perception of an increased risk of death from SARS (adjusted OR [OR]: 5.0; 95% confidence interval CI 2.06 to 9.06) live with children (adjusted OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.5 to 2.3), personal or family life affected by the outbreak of SARS (adjusted OR: 3.3; 95% CI: 2.5 to 4.3) and being treated in a manner different from working in a hospital (adjusted OR: 1.6; 95% CI: 01.02 to 02.01). Moreover, in the same study objective to work in a management or supervisory (adjusted OR: 0.6; 95% CI: 0.4 to 0.8), the belief that preventive measures in the workplace were sufficient (adjusted OR: 0.4; 95% CI 0.3-0.5) and have 50 or more years (adjusted OR, 0.6; 95% CI 0.4-0.9) was associated with decreased concern about the pandemic.

In two of the 17 items you decide to use a questionnaire (GH28 and GH12) to specifically measure anxiety levels. S. Verma et al.15 studied during the SARS pandemic in China the difference in terms of psychological morbidity among physicians and practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine, thus proving that stigma and PTSD was higher among general practitioners (p '0.05). However, LA Nickell. et al.6 comparing all health workers found that nurses were those who had been most affected in their work on a psychological level, with statistically significant differences (p '0.001) 45.1% (37/82) of the nurses, compared to 33.3% (66/198) of professional allied health care, 17.4% (8/46) of physicians and 18.9% (28/148) of staff does not work in patient care. Furthermore the author mentions that the factors significantly associated with the presence of emotional distress are: being a nurse (adjusted OR: 2.8; 95% CI: 01.05 to 05.05), the situation of part-time employment (adjusted OR: 2.6, 95% CI 1.2 to 5.4), the lifestyle affected by the outbreak of SARS (adjusted OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.4 to 3.5) and impaired the ability to do your job because of preventive measures (OR adjusted 2.9; 95% CI: 1.9 to 4.6).

Two authors refer to the workload, from the psychological point of view, that pandemics occur in health care workers, finding none of the 17 references any physical load. Shiao JS-C. et al.11 studied the factors influencing decide to abandon their work on nurses during the SARS pandemic finds that 49.9% of them perceived increase in workload. L. Vinck et al.16 obtained better results when valuing during pandemic influenza A (70.5% increase in workload).

Adoption and adherence to preventive measures

Regarding preventive measures ae both Vinck's article L. et al.16 like Martin SD et al.5 coincide more or less in the percentage of compliance with them (88% versus 92%). Furthermore, the article Parker. MJ. et al.8 obtained that measures between healthcare personnel are considered most effective are: use of isolation rooms (4.6 of 5 points with p: 0.02 95% CI: 4.5-4.8) respirator (4.5 / 5 p. 0001 p5% CI: 4.3-4.6) and handwashing (4.6 with p: 0.03 95% CI: 4.4-4.7) and with respect to the latter, the doctors informed wash his nurses and auxiliary (4.9 v 4.5 and 4.5, respectively; p '0.05).

In the study of LA Nickell. et al.6 is seen as respondents who considered the SARS high risk to public health reported greater compliance with handwashing (4.8 v 4.4) always mask utilization (3.9 v 3.2) and gloves (3.6 v 2.9) with p '0.05), gowning (4.9 v 4.7) or mask when examining patients (5.00 v 4.8). Instead eye protection (3.4 v 3.0) is not considered necessary addition, the use of a respirator caution was most frequently cited as most annoying and so considered it, 92.9% described it as a physical discomfort.

With respect to other preventive measures, Articles Wong WCW. et al.18 and CC Hsu et al.2 discuss disagreements enforce quarantine measures. In his study in Taiwan during the SARS pandemic to 312 nurses, objective nurses were less likely to cooperate with quarantine measures when they had less knowledge about SARS (OR 3.66 95% CI. 1.99-6.75) when expressed less fear (OR 3.19 95% CI. 1.85-6.21) and when not working well health centers (OR: 2.16 95% CI 1.17-4.00). With regard to information on pandemics, there is controversy regarding the sources used to obtain it. L. Vinck et al.16 in their study objective that 48% looked at the information center of reference. Instead, La Torre G et al.4 in a work on the SARS pandemic in which he compared the behavior and attitude of physicians in general population, stresses that the main source of information for physicians were internet (41.5%) and the second hospital internal (33.1%) while the rest of the obtained television population (34.1%) followed by internet (30.9%). Another important fact based on the information we found in the study of L. Vinck et al.16 in which it is found that between 71-97% of all health personnel informing patients about protective measures. However Tolomiczenko GS. et al.13 found that nurses were less informed and less involved in decision-making and were the most indicated that preventive measures were not strict enough.

An important point also found to do this review, is the question of the lack of training, something that is spoken in two of the articles included in this review. Wong ELY. et al.17 in their study of nurses during the swine flu pandemic, says that 76.9% of them do not want to work, and 43.6% are not trained to care for patients with influenza. Something similar, but referred to the medical staff, is what is Wong WCW. et al.19 to compare doctors in Hong Kong and Toronto during the SARS pandemic, aiming to 84.6% and 80.0% of Hong Kong and Toronto respectively lacked training in infectious disease control (68.1% and 73.5% respectively); and this fact was that they were more likely to request more complementary tests, especially doctors Hong Kong (OR 37.8, 95% CI 12.65-113.06).

The perception of the pandemic, both positive and negative factors the same, and agree or disagree with preventive measures is a recurring theme in several of the articles reviewed. So, Tan WM. et al.12 in their study notes that 84% of respondents agreed with the action taken. However when the question focuses only on the medical population, their work is that 72% of doctors say the measures negatively influenced their working day. And 34.6% of them described it as excessive and exaggerated.

Hsu C-C. et al.2 speaks of the lack of confidence of nurses to the pandemic and the preventive measures taken by noting that 71.9% of them showed a general lack of confidence. Also found three factors that this is associated: the greater perceived severity (OR: 0.58 with IC.95% from 0.35 to 0.99), daily performances epidemic (OR: 2.6 IC.95% 1.28-3.98) and number of cases in the community (OR: 2.1 IC.95% 1.13-4.31); in contrast with this, Nickell LA. et al.6 also says in a study conducted during the SARS pandemic, most health workers who took part in the study were as adequate preventive measures taken (74.1% of the sample). The author also mentions in his study of the three negative effects that the pandemic has had as health personnel including financial losses, the feeling of being treated differently by the general population to work in a hospital and the change in the style of personal and family life he had led.

Among the changes in lifestyle, health workers mostly speak during the pandemic try to avoid attending public spaces and avoid contact with family or friends. But not only talk about the negative of the pandemic, workers also found positives in the pandemic, 58% of them reported at least one positive effect. The positive effects most frequently mentioned are feeling greater awareness of disease control (41.1%), the finding of the pandemic as a learning experience (26.4%) and a greater sense of unity and cooperation (23.8%). Associated with these positive effects, especially at greater sense of unity and cooperation are the results found by Wong WCW. et al.19 This author finds that Family Physicians of Hong Kong and Toronto SARS not associated with loss of income, whether either a greater willingness and commitment either by the degree of satisfaction in handling SARS, showing that in both countries were willing to take responsibility and get involved.

In two of the seventeen articles reviewed the risk of contagion and risk perception thereof by the health sector are mentioned. Nukui Y. et al.7 studied the risk of infection during the influenza pandemic among different groups of health workers and finding no increased risk of seropositivity (OR: 5.25) between nurses and doctors as well as pediatric staff, emergency and internal medicine (OR: 1.98). Shiao JS-C. et. al.11 refers to the risk perception of it during the SARS pandemic and gets a 71.9% perceived risk of infection, 32.4% felt that people avoided them for their work and 7.4% seriously considered abandoning his post work.

Joining Vaccination Programs

Three of the nine articles that talk about swine flu vaccination mentioned. Tanto H. Seale et al.9 in their study of vaccination among health care workers in Beijing, and Torun SD. et al.14 in a very similar study but in Istanbul, speak vaccinated similar percentage (25% and 23.1% respectively). In both studies agree that the possible side effects are the most influential factor on adherence to vaccination (61% and 76.1% respectively) Regarding the sector population vaccine more both Torun SD. et. al.14 as La Torre G. et al.4 agreed that the group of doctors vaccinate more compared to the rest (X²: 20,23). Torun SD. et al.14 also objective that 59.9% of doctors recommend vaccination to their patients.

Conclusions and discussion

We have not found any systematic review published to date that values the behavior of health professionals in pandemic situations. In our review the level of evidence found according Sign Criteria is three as it is in all cases of cross-sectional studies. So although it does not involve a higher level of evidence provides information on areas for improvement to future health emergencies. Table 10 summarizes the main findings and limitations found in each article and progress found by the authors.

In relation to vaccination among health professionals is demonstrated that seropositivity against H1N1 is an occupational risk factor among health workers (Nukui et al.7) and is therefore a priority group for vaccination of high risk contagion. Despite this vaccination levels are insufficient. You need awareness (Seale et al.9) to health on the need for vaccination and thus must receive training and information science (Torun et al.14) on the safety and efficacy of vaccines as the factors most commonly associated with rejection were concerns about its adverse effects and the belief that the vaccine had not been adequately tested. The acceptance of a new vaccine will be more successful when placed in the context of a pandemic because it is driven by it (Seale et al.9). Not available yet tested vaccine against SARS in humans although there are investigations in animal models.

Another important aspect is the low use by the medical staff of the scientific literature available (Torun et al.14; Vinck et al.16; Wong et al.17 and La Torre et al.4). Although both pandemics WHO, CDC, the Ministries of Health of the countries and health centers themselves have guides available to the management of these diseases were underused. It is essential in the face of new pandemics that health will improve their training and for it to use resources with proven scientific literature evidence to avoid the alarm and false beliefs (Tolomiczenko et al.¹³). This training in epidemiology and health contingencies to be improved since the start of training during the time students (Idrovo et al.³).

In general preventive measures in the two pandemics were well appreciated and followed by professionals. A factor influencing acceptance is the lethality of the infectious agent. So the more lethal than the most effective infectious agent be perceived preventive measures (Parker et al.8 and Tan et al.12 WM). Another factor is the information provided by the authorities both in content and in form. Acceptance would be higher if it were accompanied by good communication explaining the uncertainty of the authorities and the benefits of individual preventive measures (Tan et al.12 WM). This would increase the use of PPE and its proper use. The monitoring would be greater if the training of health personnel (Vinck et al.16; Nickell et al.6) were improved, health policy and clinical practice (Wong et al.18 WCW) developing more participatory policies (CC Hsu et al.2) and developing control equipment less restrictive infections (Parker et al.8).

In our review we found two articles by Wong WCW18,19 en relation to family physicians and their response to the SARS pandemic. The first explains how the SARS changed clinical practice of family physicians and the second relates how health centers became massive. Family physicians are a key group pandemics since often are the first to come into contact with patients without the means or personal protection measures that exist in hospitals and well ahead of a certain infectious disease that is a trivial process or a more serious case as may be the SARS is not possible by the huge volume of patients and the common presentation of infectious diseases. Thus it is necessary to support primary care systems and improve collaboration between them and hospitals (Wong WCW et al.19).

In many of the articles reviewed reference to the psychosocial impact of the pandemic on health workers and stigma that generates the rest of the population is made. During a pandemic, we have observed that there is an important workload increase has a negative impact on their quality of life, which generates stress, but this is increased if we add the concern spread of health and what more distress them is to infect their families. This makes them think in some cases even leave their job which would bring disastrous consequences for the rest of the population because there would be fewer health personnel willing to work the greater the demand of patients. It is necessary to explore the psychological needs and treat them well as giving emotional support to health workers during pandemics (Shiao et al.11, Verma S et al.15) suitable. Proporcionar EPIS increase their perception of safety and instruct them in the proper handling (Martin et al.5 SD). You also provide training to cope with the increase in labor demand (ELY Wong et al. 17), which would make fewer workers the option of not going to work arise. The workload is a problem we've seen in these two pandemics but every year you can see with the arrival of seasonal flu. One solution is to temporarily increase the workforce (Vinck et al.16) at all levels despite the economic crisis or other aspects that influence the refusal to do so.

This review demonstrates that although between SARS and influenza A was several years the problems with the health sector and its modus operandi wrong in some respects and inadequate information provided by the authorities was repeated. We have not found scientific literature on these issues and Ebola, last pandemic that we are living, but have raised the same issues in relation to the lack of information provided by health authorities, inadequate training about the virus and its mechanisms transmission or proper use of personal protective equipment or even the availability of the same in health centers. Also the negative psychosocial effects for staff working in contact with patients have been relevant.

Limitations

The results of this review are limited by the characteristics of each revised labor shortages and discussed in all cases of cross-sectional studies with low scientific evidence. Besides the heterogeneity of the studies and the factors studied each not allow firm conclusions on any of the results. Another limitation is that although in both cases are infectious diseases that caused the pandemic can not overlap because it's different agents with different mechanisms of transmission and lethality and affected different populations.

Acknowledgements

The National Library of Health Sciences Health Institute Carlos III by articles and provided assistance with the literature search. A National School of Occupational Medicine and its director for their assistance in preparing this review.

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Belén Collado Hernández

Residente Medicina del Trabajo UD Cantabria

Mutua Montañesa. Cantabria. España.

Teléfono: 636 513 212

Correo electrónico: belencollado@hotmail.com

Recibido: 13-03-15

Aceptado: 05-05-15

Bibliographic references

1. Alenzi FQ. H1N1 update review. Saudi Medical Journal. 2010;31(3):235-46. [ Links ]

2. Hsu C-C, Chen T, Chang M, Chang Y-K. Confidence in controlling a SARS outbreak: experiences of public health nurses in managing home quarantine measures in Taiwan. Am J Infect Control. mayo de 2006; 34(4):176-81. [ Links ]

3. Idrovo AJ, Fernández-Niño JA, Bojórquez-Chapela I, Ruiz-Rodríguez M, Agudelo CA, Pacheco OE, et al. Perception of epidemiological competencies by public health students in Mexico and Colombia during the influenza A (H1N1) epidemic. Rev Panam Salud Publica. Octubre de 2011; 30(4):361-9. [ Links ]

4. La Torre G, Semyonov L, Mannocci A, Boccia A. Knowledge, attitude, and behaviour of public health doctors towards pandemic influenza compared to the general population in Italy. Scand J Public Health. Febrero de 2012; 40(1):69-75. [ Links ]

5. Martin SD. Nurses' ability and willingness to work during pandemic flu. J Nurs Manag. Enero de 2011; 19(1):98-108. [ Links ]

6. Nickell LA, Crighton EJ, Tracy CS, Al-Enazy H, Bolaji Y, Hanjrah S, et al. Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: survey of a large tertiary care institution. CMAJ. 2 de marzo de 2004; 170(5):793-8. [ Links ]

7. Nukui Y, Hatakeyama S, Kitazawa T, Mahira T, Shintani Y, Moriya K. Pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus among Japanese healthcare workers: seroprevalence and risk factors. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. Enero de 2012; 33(1):58-62. [ Links ]

8. Parker MJ, Goldman RD. Paediatric emergency department staff perceptions of infection control measures against severe acute respiratory syndrome. Emerg Med J. Mayo de 2006; 23(5):349-53. [ Links ]

9. Seale H, Kaur R, Wang Q, Yang P, Zhang Y, Wang X, et al. Acceptance of a vaccine against pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus amongst healthcare workers in Beijing, China. Vaccine. 11 de febrero de 2011; 29(8):1605-10. [ Links ]

10. Shapiro SE, McCauley LA. SARS update: Winter, 2003 to 2004. AAOHN J. Mayo de 2004;52(5):199-203. [ Links ]

11. Shiao JS-C, Koh D, Lo L-H, Lim M-K, Guo YL. Factors predicting nurses' consideration of leaving their job during the SARS outbreak. Nurs Ethics. Enero de 2007;14(1):5-17. [ Links ]

12. Tan WM, Chlebicka NL, Tan BH. Attitudes of patients, visitors and healthcare workers at a tertiary hospital towards influenza A (H1N1) response measures. Ann Acad Med Singap. Abril de 2010; 39(4):303-4. [ Links ]

13. Tolomiczenko GS, Kahan M, Ricci M, Strathern L, Jeney C, Patterson K, et al. SARS: coping with the impact at a community hospital. J Adv Nurs. Abril de 2005; 50(1):101-10. [ Links ]

14. Torun SD, Torun F. Vaccination against pandemic influenza A/H1N1 among healthcare workers and reasons for refusing vaccination in Istanbul in last pandemic alert phase. Vaccine. 9 de agosto de 2010; 28(35):5703-10. [ Links ]

15. Verma S, Mythily S, Chan YH, Deslypere JP, Teo EK, Chong SA. Post-SARS psychological morbidity and stigma among general practitioners and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singap. Noviembre de 2004;33(6):743-8. [ Links ]

16. Vinck L, Isken L, Hooiveld M, Trompenaars M, Ijzermans J, Timen A. Impact of the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic on public health workers in the Netherlands. Euro Surveill. 2011; 16(7). [ Links ]

17. Wong ELY, Wong SYS, Kung K, Cheung AWL, Gao TT, Griffiths S. Will the community nurse continue to function during H1N1 influenza pandemic: a cross-sectional study of Hong Kong community nurses? BMC Health Serv Res. 2010; 10:107. [ Links ]

18. Wong WCW, Lee A, Tsang KK, Wong SYS. How did general practitioners protect themselves, their family, and staff during the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong? J Epidemiol Community Health. Marzo de 2004; 58(3):180-5. [ Links ]

19. Wong WCW, Wong SYS, Lee A, Goggins WB. How to provide an effective primary health care in fighting against severe acute respiratory syndrome: the experiences of two cities. Am J Infect Control. Febrero de 2007; 35(1):50-5. [ Links ]

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Internet). (Citado 24 de enero de 2015). Recuperado a partir de: http://www.cdc.gov/. [ Links ]

21. Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Internet). (Citado 26 de enero de 2015). Recuperado a partir de: http://www.isciii.es/ISCIII/es/contenidos/. [ Links ]

22. OMS (Organización Mundial de la Salud (Internet)). WHO. (Citado 24 de enero de 2015). Recuperado a partir de: http://www.who.int/es/. [ Links ]

23. STROBE Statement: Home (Internet). (citado 26 de enero de 2015). Recuperado a partir de: http://www.strobe-statement.org/. [ Links ]

text in

text in