My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO  Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.96 n.7 Madrid Jul. 2004

| ORIGINAL PAPERS |

Quality of life (GIQLI) and laparoscopic cholecystectomy usefulness in patients

with gallbladder dysfunction or chronic non-lithiasic biliary pain (chronic

acalculous cholecystitis)

M. Planells Roig, J. Bueno Lledó, A. Sanahuja Santafé and R. García Espinosa

Institute of General Surgery and Digestive Diseases (ICAD). Clínica Quirón. Valencia, Spain

ABSTRACT

Objective: the aim of this study was to evaluate the incidence, clinical features and role of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) in patients with chronic acalculous cholecystitis (CAC) in comparison with a control group of patients who underwent cholecystectomy for chronic calculous cholecystitis (CCC).

Material and methods: prospective evaluation of 34 patients with CAC in contrast with 297 patients with CCC.

Outcome measures: clinical presentation, quality of life using the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI), usefulness derived from the therapeutic procedure as measured in quality of life units by GIQLI, and clinical efficacy at one year of follow-up.

Results: the incidence of complicated biliary disease was higher in CAC (27%), in comparison with CCC (13.8%). The histological study of the excised gallbladder revealed a higher incidence of cholesterolosis associated with chronic cholecystitis in the CAC group (64.9%). GIQLI showed significant differences between preoperative and postoperative measurements in both groups. The associated usefulness of LC was similar in both groups (73 versus 67.3 per cent), confirming an important increase in quality of life for both categories.

Conclusions: the incidence of CAC is 11 per cent with a high association with cholesterolosis. Quality of life and LC usefulness are similar to those of patients with CCC. Due to the fact that cholecistogammagraphy is a technique not available in daily clinical practice, and that oral cholecystography and dynamic ultrasound are reliable when a positive result is obtained, extended clinical evaluation is still the most reliable indicator for cholecystectomy.

Key words: Quality of life. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Gallbladder dysfunction. Chronic acalculous cholecystitis.

Planells Roig M, Bueno Lledó J, Sanahuja Santafé A, García Espinosa R. Quality of life (GIQLI) and laparoscopic cholecystectomy usefulness in patients with gallbladder dysfunction or chronic non-lithiasic biliary pain (chronic acalculous cholecystitis). Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2004; 96: 442-451.

Recibido: 17-11-03.

Aceptado: 27-01-04.

Correspondencia: M. Planells Roig. ICAD. Clínica Quirón. Avda. Blasco Ibáñez, 14. 46010 Valencia. e-mail: mplanells@bsab.com

INTRODUCTION

Chronic acalculous cholecystitis (CAC) is a controversial clinical condition accounting for 5 to 20 per cent of all cholecystectomies (1-3). Patients refer colic biliary pain but ultrasounds show no stones. Most patients are subjected to multiple and repetitive explorations without reaching a final diagnosis. Diagnostic techniques have included dynamic ultrasonography (DUS), oral cholecystography (OC), and dynamic cholecystogammagraphy (DCG) (1,4,5), although accuracy to predict clinical results remains uncertain (6-9) and surgical indications are still based on clinical grounds (10).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients included in this study underwent cholecystectomy from 2001 through 2002 and divided into two groups: preoperative diagnosis of chronic acalculous cholecystitis (CAC) and those diagnosed with chronic calculous cholecystitis (CCC).

Similar to previous studies (1,9), chronic acalculous cholecystitis was defined as a heterogeneous group of patients with one of the following criteria: a) typical biliary pain with negative ultrasound examination (performed at least twice) and a clinical diagnosis of gallbladder dysfunction (GBD); b) acute acalculous cholecystitis with ultrasound findings of acute cholecystitis but no stones. In this group of patients, repeated attacks of biliary pain after the cholecystitis episode led to a diagnosis of gallbladder dysfunction; c) acute pancreatitis without ultrasound findings of biliary sludge, stones or gallbladder polypoid lesion (PGBL). In this group, magnetic resonance cholangiography ruled out common bile duct pathology or periampular lesions. Other causes of pancreatitis were also excluded (chronic alcohol abuse, abdominal trauma, hyperlipidemia or hyperparathiroidism); and d) patients with typical biliary pain or biliary dyspepsia associated with PGBL.

Gallbladder dysfunction (GBD) was defined as an epigastric or right upper quadrant pain with or without dorsal irradiation, typically presenting after oral intake, of variable duration and chronic presentation (at least 3 episodes per month), that usually responded to spasmolytic agents or restricted fat-free diet. All patients included were studied at least twice with ultrasounds, which excluded stones, sludge or PGBL. In this group of patients the following tests were also performed: a) Helicobacter pylori determination (urease tests); b) upper gastrointestinal tract radiographic series or esophagogastroscopy; and c) oral cholecystography or dynamic ultrasounds or both.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) was indicated as described elsewere (10) when: biliary symptoms were persistent and chronic or acute cholecystitis or pancreatitis developed, and, in the GBD group, when OC or DUS where positive or, if negative, when a clinical evaluation was considered positive. The latter group of patients was informed of the possibility of persistent symptoms due to a lack of accuracy of diagnostic tests and unavailability of DCG.

OC was performed as usual with fat meal stimulation and gallbladder diameter measurements. It was considered positive when a decrease of more than 50% was not obtained.

DUS was performed with fatty meal also, and gallbladder kinetics was measured with the following formula: (baseline volume - post-stimulation volume / baseline volume) x 100. As in previous studies, it was considered abnormal when a decrease of more than 50% was not obtained (11).

LC results were evaluated in the following terms: a) histological findings demonstrating chronic cholecystitis with or without cholesterolosis; b) quality of life decrease as expressed by patients using GIQLI (12) in the preoperative interview. In our study, maximum GIQLI (healthy patients) scores ranged from 159 to 165, as zero values were excluded in order to identify missing values; c) evaluation of quality of life 3 months after surgery (GIQLI) and an estimation of the usefulness of the surgical procedure, defined as positive when an increase of 20 units in quality of life was reached; and d) clinical follow-up during the first year in order to exclude clinical recurrence, and fitness of diagnosis and therapeutic procedure.

All patients underwent ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy as previously described (13-15).

RESULTS

Patients included in the study were: 37 patients with CAC and 297 with CCC.

Median age was 44.2±14.2 years for CAC in comparison with 55.2±13.6 years in the CCC group (p = 0.001). Sex distribution was similar for both groups, with a male to female ratio of 1/2.7 in the CCA group and 1/3.3 in the CCC group (χ2 = 0.262, NS). No differences in operating time were found between groups (42.4±23.1 minutes vs 49.9±23.5 minutes; NS).

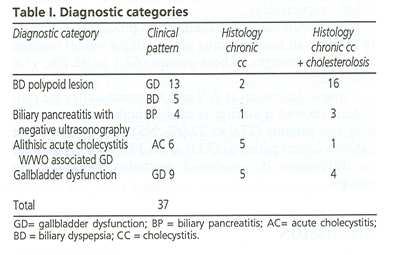

Table I shows the diagnoses or clinical presentation of patients with clinical diagnosis of CAC and associated histological findings (chronic cholecystitis versus chronic cholecystitis associated with cholesterolosis).

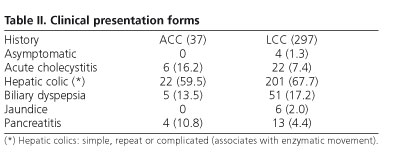

Table II summarizes the clinical presentation in both groups of patients, CAC and CCC. Complicated forms of biliary disease (acute cholecystitis and pancreatitis) are higher in the CAC group (27.0 %) than in the CCC group (13.8%). Patients who needed hospital admission due to complicated biliary disease were also higher in the latter (27%) than in the former group (16.5%; χ2 = 3.04; p = 0.011).

Associated gastrointestinal symptoms, mainly symptoms of peptic ulcer or gastroesophageal reflux disease, did not show statistically significant differences between both groups [51.4 vs 49.2%; χ2 = 0.063, NS].

Functional gallbladder tests were only performed in patients diagnosed with GBD. OC was performed in 13 patients (10 positive). DUS was only performed in 5 (all negative).

Histological analysis of the excised gallbladders demonstrated chronic cholecystitis in 35.1% of patients in the CAC group and in 93.2% in the CCC group. Chronic cholecystitis associated with cholesterolosis was found in 64.9% of patients in the former group and in 6.8% of patients in the latter group (χ2= 20.7; p < 0.0001).

GIQLI was evaluated in 97 patients. Preoperative value (median) was 119.1±28.6 in the CAC group (n = 14) in comparison with a postoperative value of 143.1±24.1 (p < 0.01). In the CCC group (n = 83) the preoperative value was 128.9±25.4 and the postoperative value 146.9±17.3. These values were not different from that found in the CAC group of patients (p values, 0.192 and 0.446, respectively).

The usefulness of the therapeutic procedure (increase in 20 units in postop minus preop GIQLI value) reached similar percentages in both groups (57.1 vs 42.2%; χ2 = 1.08, NS).

Clinical follow-up at 7, 9 and 12 months after the procedure showed a similar results in both groups concerning lost patients (27.0 vs 32.0%; NS) and asymptomatic patients (cured patients) (73.0 vs 67.3%; NS). There were no differences in associated morbidity between both groups.

DISCUSSION

One of the most controversial and frequent dilemmas for surgeons in clinical practice, is what should advise to patients referred for recurrent acalculous biliary pain (16). CAC is a controversial issue since: a) histological diagnosis is usually retrospective; b) some clinical conditions are rather diagnosed instead of CAC, as gallbladder stones, common bile duct stones, Oddi dysfunction, gastroesophageal reflux and irritable bowel syndrome; c) the only reliable preoperative diagnostic tool is dynamic cholecistogammagraphy while oral cholecystography and dynamic ultrasonography remain as second-line diagnostic techniques; and d) clinical resolution of symptoms is not guaranteed.

Although in the past, cholecystectomy was selected for patients with complicated gallstone disease, the feasibility of LC deserves consideration for the treatment of CAC, but keeping in mind that symptomatic relieve will not reach all patients (3,9,17); therefore, the role of LC in GBD is still controversial.

CAC includes two different conditions: a) true CAC with no findings in US examination (performed at least twice), which includes two different histological categories, chronic cholecystitis and chronic cholecystitis associated with cholesterolosis (the latter not diagnosed by US or OCG). Clinical patterns associated with this condition include: gallbladder dysfunction (GBD) or chronic acalculous biliary pain, acute acalculous cholecystitis and acute biliary pancreatitis (the latter associated with cholesterolosis) (18). Moreover, the incidence of cholesterolosis in patients with a diagnosis of GBD is 0 to 60 per cent (19,20), and a preoperative misdiagnosis of cholesterolosis is not rare as US and/or OCG have a low diagnostic power for this condition (21); and b) CAC associated with PGBL (polypoid gallbladder lesions), most of them an expression of gallbladder cholesterolosis. Clinical presentation includes GBD (acalculous biliary colic) and biliary pancreatitis. Histological studies show cholesterolosis associated with a variable degree of chronic cholecystitis. In the majority of series cholesterol polyps are the most frequent PGBLs (22,23). In this group LC is clearly indicated when biliary symptoms are associated (24) and the typical histological finding is cholesterolosis (25). Surprisingly, most studies about acalculous biliary colic, chronic acalculous cholecystitis or GBD do not include cholesterolosis patients (8,26).

Nevertheless, the usefulness of LC in CAC has been demonstrated in patients with or without associated cholesterolosis (19), including patients with or without impairment of the ejection fraction as demonstrated by DCG.

CAC incidence reaches 23 per cent in most cholecystectomy series (1), and the histological diagnosis of CAC is more frequent than previously admitted (6,7,27). Histological findings are similar to those found for gallstones. Cholesterolosis (28) may be diagnosed as small polyps in US examination; as it usually is a flat cholesterolosis, this explains the low sensitivity of US for its diagnosis (21). This makes idiopathic pancreatitis a frequent diagnosis in these patients unless a microscopic biliary examination is carried out. In patients with polypoid cholesterolosis, US diagnosis is feasible although this subgroup of patients belong to PGBLs.

In patients with CAC, a low ejection fraction has been demonstrated and histological studies have revealed chronic cholecystitis, cholesterolosis or no findings (8,19,30). The significance of histological findings is not clear (31), as inflammation extent may not be related to symptoms (32). Moreover, although most patients who benefit from LC have a low ejection fraction in DCG, the group of patients in whom CGD is normal also benefit from LC (8,19,30-33), and in this group the frequency of histological findings is similar. Therefore a histological normal gallbladder may have an abnormal DCG probably due to dyskinesia (34,35). Due to the previously described facts, the selection of patients for surgery based on clinical grounds is still of primary importance (10,36), including groups where such selection is made only on clinical grounds and a single US examination (10).

As far as the presenting clinical picture is a complicated condition, such as acute cholecystitis or acute pancreatitis, indications for surgery is clear (19). Nevertheless, a GBD diagnosis is infrequently considered in patients with symptoms of biliary colic but with negative US examination (17). Most of these patients have epigastric pain or right upper quadrant pain with or without dorsal irradiation, typically exacerbated by meals. Due to their negative US examination, most of these patients undergo repeated explorations and are finally diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome or functional dyspepsia (17).

Therefore, the most relevant fact of CAC (20) is that patients are repeatedly investigated with normal results, and are finally diagnosed by the exclusion of functional dyspepsia with no effective treatment, thus becoming a frustrating condition for patients and doctors alike due to repeat explorations and medical visits without clinical resolution. Moreover, due to a lack of understanding of this disease by medical specialists, surgical indications are controversial in all medical areas related to this problem (surgeons, primary care physicians, etc.), which leads to repeat visits and explorations.

There is scientific evidence that patients with a GBD diagnosis have a functional gallbladder emptying dis-order that results in a typical biliary pain (11,27,37). How-ever, this diagnosis requires a dynamic demonstration (11). The underlying disorder may be related to three different disorders: a) Oddi sphincter dysfunction; b) cystic duct syndrome; and c) gallbladder dyskinesia which may be primary or secondary to chronic cholecystitis (17,38). The latter is explained by asynchronous gallbladder contraction with Oddi sphincter relaxation, and it is the source of symptoms in patients with CAC and abnormal DCG.

The most reliable diagnostic tool is DCG (8,11). Nevertheless, due to its complexity and difficult availability in clinical practice, other studies such as dynamic ultrasonography are currently under evaluation (11,33).

Multiple studies have demonstrated the usefulness of LC in patients with GBD with abnormal DCG (30,33,39). Results (17) show that patients with GBD undergoing LC have an important clinical benefit regardless of histological findings. This suggests that histological findings are not solely responsible for the clinical picture, and LC is equally effective in patients with or without underlying histological disease.

The complexity of an accurate preoperative diagnosis of GBD remains a lack of accurate diagnostic tests and their availability.

Oral cholecystography gives information about the gallbladder function, and lack of visualization is related to acute or chronic cholecystitis (20). Moreover, the persistence of contrast 24 hours following the test, as demonstrated by a plain abdominal study, suggests cholesterolosis, and this histological finding accounts for 60 per cent of patients with GBD (19).

Dynamic ultrasonography (DUS) allows a semiquantitative estimation of gallbladder emptying by extrapolating volume changes following stimulation (11). Results using the ellipsoid method are optimal although it has important interobserver and intraobserver variability (11). Moreover, changes in morphology associated or not with emptying and gallbladder secretion are not controlled phenomena that may correlate with false volume determinations (40,41).

Therefore DUS (11) is not correlated to DCG and in GBD patients it may not be of diagnostic value when compared to DCG (11).

While OCG and DUS are poorly correlated, this makes preoperative diagnosis difficult and so it is still necessary to select patients through clinical examination.

In conclusion, the incidence of CAC reached 11.1 per cent of patients undergoing cholecystectomy. The prevalence of associated gastrointestinal symptoms was similar for both groups. Quality of life is similarly affected by both CAC and CCC. Complicated biliary disease and hospital admissions were higher in the group with CAC. In quality of life terms, the usefulness of LC was similar in both groups, thus making its surgical indication reason-able. Histological studies were positive in 100 per cent of patients, with a 64.8 per cent of cholesterolosis, similar to previous studies and higher than in the CCC group. Clinical follow-up (one year) demonstrated the clinical efficacy of LC in the CAC group. Diagnostic tests, OCG and DUS showed heterogeneous results, and LC was indicated mainly on clinical patterns, that is, a GBD diagnosis or previous history of complicated biliary disease (acute cholecystitis or pancreatitis). Therefore, clinical selection remains the most important criterion for surgical selection.

REFERENCES

1. Chen PF, Nimeri A, Pham QH, et al. The clinical diagnosis of chronic acalculous cholecystitis. Surgery 2001; 130: 578-83. [ Links ]

2. Jones Monaham K, Gruemberg JC. Chronic acalculous cholecystitis: changes in patient demographics and evaluation since the advent of laparoscopy. J Surg Laparosc Surg 1999; 3: 221-4. [ Links ]

3. Reitter D, Aaning HL. Chronic acalculous cholecystitis: reproduction of pain with cholecystokinin and relief of symptoms with cholecystectomy. SD J Med 1999; 52: 197-200. [ Links ]

4. Jones DB, Soper NJ, Brewer JD, et al. Chronic acalculous cholecystitis: laparoscopic treatment. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1996; 6: 114-22. [ Links ]

5. Barron LG, Rubio PA. Importance of accurate preoperative diagnosis and role of adavanced laparoscopic cholecystectomy in relieving chronic acalculous cholecystitis. J Laparoendosc Surg 1995; 5: 357-61. [ Links ]

6. Frasinelli P, Wermer M, Reed JF, Scagliotti C. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy alleviates pain in patients with acalculous biliary disease. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1998; 8: 30-4. [ Links ]

7. Adams DB, Tarnasky PR, Hawes RH et al. Outcome after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for chronic acalculous cholecystitis. Am Surg 1998; 64: 1-6. [ Links ]

8. Fink Bennet D, DeRidder P, Kolozski WZ, et al. Cholecystokinin cholescintigraphy: detection of abnormal gallbladder motor function in patients with chronic acalculous gallbladder disease. J Nucl Med 1991; 32: 1695-9. [ Links ]

9. Westlake PJ, Hernshfield NB, Kelly JK, et al. Chronic right upper quadrant pain without gallstones: does HIDA scan predict outcome after cholecystectomy? Am J Gastroenterol 1990; 85: 986-90. [ Links ]

10. Brosseuk D, Demetrick J. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for symptoms of biliary colic in the absence of gallstones. Am J Surg 2003; 186: 1-3. [ Links ]

11. Pons V, Ballesta A, Ponce M, Maroto N, Argüello L, Sopena R, et al. Ultrasonografía dinámica en el diagnóstico de la disfunción vesicular: fiabilidad de un método sencillo de fácil aplicación clínica. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003; 26 (1): 8-12. [ Links ]

12. Quintana JM, Cabriada J, López de Tejada I, Varona M, Oribe V, et al. Traducción y validación del Índice de Calidad de Vida Gastrointestinal (GIQLI). Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2001; 93: 693-9. [ Links ]

13. Serralta A, Bueno J, Sanahuja A, García R, Arnal C, Guillemot M, et al. Learning curve in ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Techn 2003; 12: 320-4. [ Links ]

14. Planells M, Sánchez A, Sanahuja A, Bueno J, Serralta A, García R, et al. Gestión de la calidad total en colecistectomía laparoscópica. Calidad asistencial y calidad percibida en colecistectomía laparoscópica ambulatoria. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2002; 94: 319-25. [ Links ]

15. Serralta A, García R, Martínez P, Hoyas L, Planells M. Cuatro años de experiencia en colecistectomía laparoscópica ambulatoria. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2001; 93: 207-10. [ Links ]

16. Dwijen C, Misra Jr, Blossom GB, Fink Bennet D, Glover JL. Results of surgical therapy for Biliary Dyskinesia. Arch Surg 1991; 126: 957-60. [ Links ]

17. Yost F, Margenthaler J, Presti M, Burton F, Murayama K. Cholecystectomy is an effective treatment for Biliary Dyskinesia. Am J Surg 1999; 178: 462-5. [ Links ]

18. Parrilla Paricio P, García Olmo D, Pellicer Franco E, et al. Gallbladder cholesterolosis: an aetiological factor in acute pancreatitis of uncertain origin. Br J Surg 1990; 77: 735-6. [ Links ]

19. Kmiot WA, Perry EP, Donovan IA, Lee MJR, Wolverson RF, Harding LK, et al. Cholesterolosis in patients with chronic acalculous biliary pain. Br J Surg 1994; 81: 112-5. [ Links ]

20. Calabuig R, Castilla M, Pi F, Domingo J, Ramos L, Sierra E. Disquinesia vesicular en el cólico biliar alitásico. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 1996; 88: 770-4. [ Links ]

21. Jacyna MR, Bouchier IAD. Cholesterolosis: a physical cause of "functional" disorder. BMJ 1987; 295: 619-20. [ Links ]

22. Damore LJ, Cook CH, Fernández KL, Cunningham J, Elison EC, Melvin WS. Ultrasonography incorrectly diagnoses Gallbladder Polyps. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2001; 11: 88-91. [ Links ]

23. Yang HL, Sun YG, Wan Z. Polypoid lesion of the gallbladder: diagnosis and indications for surgery. Br J Surg 1992: 79: 227-9. [ Links ]

24. Csendes A, Burgos AM, Csendes P, Smok G, Rojas J. Late follow up of polypoid lesions of the gallbladder Smaller than 10 mm. Ann Surg 2001; 234: 657-60. [ Links ]

25. Bilhartz LE. Cholesterolosis. In: Sleissenger & Fordtran. Gastrointestinal Disease. Philadelphia: WB Saunders 1993. p. 1860-2. [ Links ]

26. Rhodes M, Lennard TWJ, Farndon JR, Taylor RMR. Cholecystokinin (CCK) provocation test: long term follow up after cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 1988; 75: 450-3. [ Links ]

27. Canfield AJ, Hetz SP, Schriver JP, Servis HT, Hovenga Tl, et al. Biliary dyskinesia: a study of more than 200 patients and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg 1998; 2: 443-8. [ Links ]

28. Berk RN, van Der Vegt JH, Lichtenstein JE. The hyperplastic cholecystoses: cholesterolosis and adenomyomatosis. Radiology 1983; 146: 593-601. [ Links ]

29. Rice J, Sauerbrei EE, Semogas P, et al. Sonographic appearance of adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder. J Clin Ultrasound 1981; 9: 336-7. [ Links ]

30. Yap L, Wycherley AG, Morphett AD, Toouli J. Acalculous biliary pain: cholecystectomy alleviates symptoms in patients with abnormal cholescintigraphy. Gastroenterology 1991; 101: 786-93. [ Links ]

31. Sunderland GT, Carter DC. Clinical application of the cholecystokinin provocation test. Br J Surg 1988; 75: 444-9. [ Links ]

32. Mackey WA. Cholecystitis without stones. Br J Surg 1934; 22: 275-95. [ Links ]

33. Misra DC, Blossom GB, Fink Bennet D, Glover JL. Results of surgical therapy for biliary diskynesia. Arch Surg 1991; 126: 957-60. [ Links ]

34. Davis GB, Berk RN, Scheible FW, Witzum KF. Cholecystoknin cholecystography, sonography and scintigraphy: detection of chronic acalculous cholecystitis. Am J Roentgenol 1982; 139: 1117-21. [ Links ]

35. Sand JA, Turganmaa VM, Koskinen MO, Makinen AM, Norback JH. Variables affecting quantitative biliary scintigraphy in asymptomatic cholecystectomized volunteers. Hepatogastroenterology 1999; 46: 130-5. [ Links ]

36. Kloiber R, Molnar CP, Shaffer EA. Chronic biliary type pain in the absence of gallstones: the value of cholecystokinin cholescintigraphy AJR 1992; 159: 509-13. [ Links ]

37. Sorenson MK, Fancher S, Lang NP, et al. Abnormal gallbladder nuclear ejection fraction predicts success of cholecystectomy in patients with biliary dyskinesia. Am J Surg 1993; 166: 672-5. [ Links ]

38. Velanovich V. Biliary dyskinesia and biliary crystals: a prospective study. Am Surg 1997; 63: 69-74. [ Links ]

39. Jagannath SB, Singh VK, Cruz Correa M, Canto MI, Kalloo AN. A long term cohort study of outcome after cholecystectomy for chronic acalculous cholecystitis. Am J Surg 2003; 185: 91-5. [ Links ]

40. Radberg G, Asztely M, Moonem M, Svanvik J. Contraction and evacuation of the gallbladder studied simultaneously by ultrasonography and 99mTc-labeled diethyl-iminodiacetic acid scintigraphy. Scand J Gastroenterol 1993; 28: 709-13. [ Links ]

41. Glickerman DJ, Kim M, Malik R, Lee S. The gallbladder also secretes. Dig Dis Sci 1997; 42: 489-91. [ Links ]

text in

text in