Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.98 no.8 Madrid ago. 2006

ORIGINAL PAPERS

Is anal endosonography useful in the study of recurrent complex fistula-in-ano?

¿Es útil la ecografía endoanal en el estudio de la fístula anal compleja recidivada?

A. M. Fernández-Frías, F. Pérez-Vicente, A. Arroyo, A. M. Sánchez-Romero,

J. M. Navarro, P. Serrano, I. Oliver, D. Costa, F. Candela and R. Calpena

Coloproctology Unit. Service of General and Gastrointestinal Surgery. Hospital General Universitario. Elche, Alicante. Spain

ABSTRACT

Introduction: performing anal endosonography in complex fistula-in-ano allows us to design a personalized surgical strategy in each case, thereby improving results. However, there are doubts in the literature as to its utility in recurrent complex fistulas. The aim of this study was to compare the utility of anal ultrasonography in the study of primary versus recurrent complex fistula-in-ano.

Patients and method: prospective study of patients diagnosed and treated for complex fistula-in-ano. Physical examination and anal ultrasonography provided data on primary track, internal opening, horseshoe extension and the presence of secondary tracks or cavities in a protocol designed specifically for the study. These assessments were subsequently contrasted with operative findings.

Results: we included 35 patients, 19 (54.3%) with primary complex anal fistulas and 16 (45.7%) with recurrent fistulas. According to the operative findings, fistulas were classified as high transsphincteric in 28 patients (80%), suprasphincteric in 6 (17.1%) and extrasphincteric in one patient (2.9%), with no differences between groups. Physical examination correctly classified 28 of the 35 fistulous tracks, in contrast to the 32 (91.4%) correctly described on ultrasonography (80%). We did not find any statistically significant differences between the primary and the recurrent fistula groups with regard to sensibility, positive predictive value and accuracy of the anal ultrasonography for any of the parameters studied.

Conclusion: the accuracy of anal ultrasonography does not decrease in recurrent complex fistula-in-ano.

Key words: Anal ultrasonography. Complex fistula-in-ano. Accuracy.

Introduction

Anorectal ultrasonography has developed greatly since the early 90s, and is one of the diagnostic techniques of choice in cases of rectal cancer (1), faecal incontinence (2) and perianal septic conditions (3).

Our studies support the utility of endoanal ultrasonography in the pre-operative study of complex anal fistulas (4,5) to determine their anatomical characteristics (6). This enables the most appropriate surgical technique to be chosen, thus reducing the high rate of post-surgical anal incontinence and recurrence -the two most common complications in the treatment of complex fistulas.

An additional problem is the structural alteration of the anal canal in cases of recurrent complex fistulas with areas of fibrosis and possible associated sphincteric lesions, which make diagnosis and treatment of this pathology even more difficult. This has led many surgeons to question the utility of anal ultrasonography in recurrent complex fistulas.

The objective of our study is to compare the diagnostic accuracy of anal ultrasonography in the study of recurrent and primary complex anal fistulas in patients diagnosed and treated in the Coloproctology Unit of our hospital.

Patients and methods

A prospective study of patients diagnosed with recurrent or primary complex fistula-in-ano in the Coloproctology Unit of the Hospital General Universitario de Elche between March 2000 and March 2002. We included patients with suspicion of high transsphincteric, suprasphincteric or extrasphincteric fistulas according to Parks's classification (7).

This study was accepted by our hospital's Ethics Committee. We explained the different therapeutic and diagnostic procedures in detail to each patient, and they gave their specific informed consent to surgery.

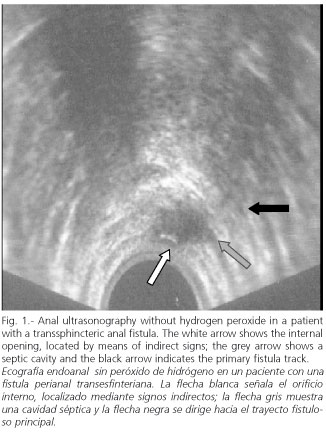

An exhaustive physical examination and anal ultrasonography was done in all patients prior to surgery. Physical examination and anal ultrasonography provided data on primary track, internal opening, horseshoe extension and the presence of secondary tracks or cavities. The ultrasonography was done using a LOGICTM 400 CL PRO ultrasonograph (General Electrics) with a multi-frequency 180º probe (5-11 Hz). No preparation of the colon was considered necessary. With the patient lying on his left side we performed the first part of the ultrasound study without contrast (Fig. 1).

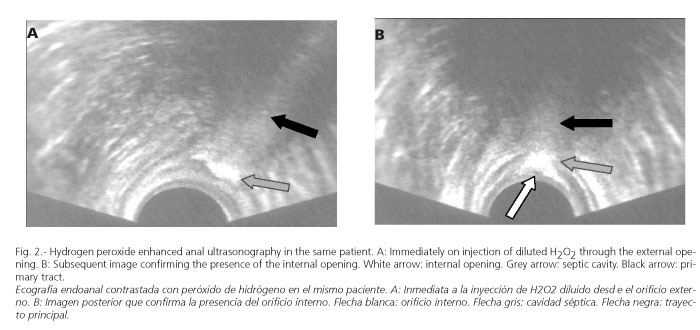

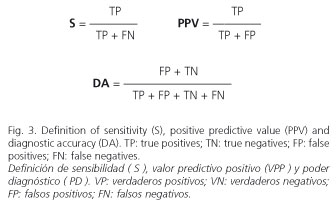

A flexible intravenous cannula (Abbocath) was then inserted into the external opening, through which hydrogen peroxide diluted to 50% was injected, and the study repeated (Fig. 2). Physical examination and ultrasonography were always done by two different surgeons belonging to the Coloproctology Unit of Hospital Universitario de Elche. The physical examination and ultrasonography findings were recorded in a protocol for collecting data designed specifically for this study. These data were subsequently contrasted with operative findings, comparing, on the one hand, physical examination findings with those of ultrasonography and, on the other, ultrasonography findings between the groups of recurrent and primary fistulas. To do this we calculated the sensitivity, positive predictive value and diagnostic accuracy of anal ultrasonography for each of the parameters studied (Fig. 3).

The Mann-Whitney U test was used to contrast quantitative variables between groups. Fisher's exact test and Pearson's χ2 test were used to contrast proportions and qualitative variables. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

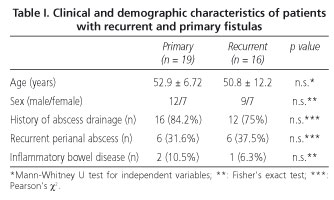

Of the 35 patients studied, 19 (54.3%) had a primary complex fistula and 16 (45.7%) a recurrent complex fistula. The demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in table I. There were no significant differences between the recurrent and primary fistula groups, with both groups being homogeneous and comparable.

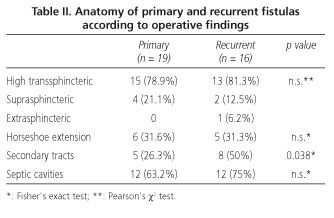

The anatomic characteristics of the recurrent and primary fistulas are shown in table II. According to operative findings, the fistulas were classified as high transsphincteric in 28 patients (80%), suprasphincteric in 6 patients (17.1%) and extrasphincteric in one patient (2.9%). There were no differences in the nature of the primary track between the two groups, but there was a larger number of fistulas with accessory tracks and cavities in the recurrent fistula group (Table II).

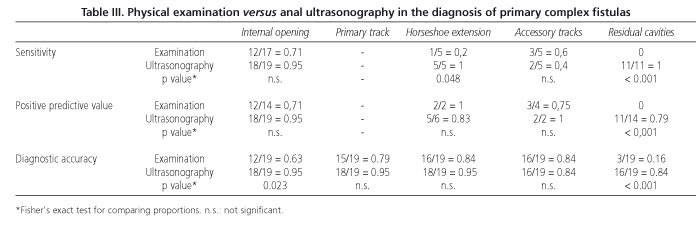

In the group of primary fistulas, physical examination correctly classified 15 of the 19 tracks (78.9%), whereas ultrasonography did so in 18 cases (94.7%). Ultrasonography exhibited more diagnostic accuracy than physical examination in locating the internal opening of the fistula, although there was no difference in sensitivity or positive predictive value. There were very significant differences, however, in sensitivity and positive predictive value in favour of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of residual septic cavities (Table III). The sensitivity of ultrasonography was also higher when determining the horseshoe extension, although there were no differences in diagnostic accuracy. There were no differences between physical examination and ultrasonography as regards the other parameters studied.

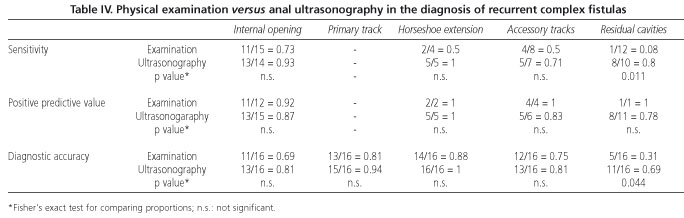

In the group of recurrent complex fistulas, physical examination correctly classified 13 of the 16 tracks (81.3%), whereas ultrasonography did so in 15 cases (93.8%). Ultrasonography also gave better results than physical examination in the diagnosis of residual septic cavities, but there were no differences as regards determination of the internal opening or the other parameters studied (Table IV).

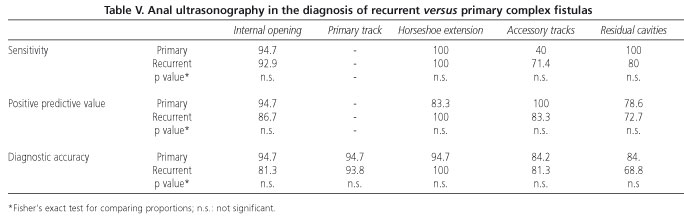

When we compare the validity of ultrasonography between the recurrent and primary fistula groups, no statistically significant differences are found in any of the parameters studied (Table V).

Discussion

The difficulty involved in diagnosing and treating complex anal fistulas makes this pathology a problem for colorectal surgeons. Fortunately, only a small percentage of perianal septic conditions may be classified as complex anal fistulas, whose high rate of recurrence and the possibility of post-surgical faecal incontinence are two of the main complications (8).

The majority of recurrences are due to chronic septic cavities or accessory tracks that were not identified during surgery, or to the impossibility of finding the internal fistula opening (9), which implies failure of the surgical technique used and persistence or reappearance of symptoms. In order to prevent this complication it is necessary to perform a thorough pre-operative study to delimit as accurately as possible the anatomic extension of the complex anal fistula (10).

To this end, different diagnostic techniques have been used with results that vary widely in terms of reliability. Thus, procedures such as fistulography (11) or computerized tomography (12) have been shown to be of little value in the study of complex fistulas, whereas anal ultrasonography and, in recent years, NMR (13,14) have proved to be the diagnostic procedures of choice in cases of complex anal fistulas.

Physical examination by an experienced surgeon, including inspection, digital examination and anuscopy, can classify the primary track correctly in more than 60% of patients, and the internal opening in up to 80% in the case of primary fistulas (14). These values decrease in patients with recurrent fistulas, due to structural alteration of the anal canal, with areas of fibrosis and/or sphincteric lesions secondary to the different episodes of infection and sequelae of previous surgery. For this reason, it is obviously necessary to use other complementary imaging tests so as to obtain acceptable post-surgical results.

Localization of the internal opening by mean of ultrasonography is one of the factors most debated in the literature. Despite using hydrogen peroxide as the contrast medium, as described by Cheong et al. in 1993 (15), the results of the different studies vary greatly. Poen et al. (16) detected the internal opening correctly in 48% of the cases; Ratto (5) and Ortiz (17) reported results of 54 and 62% respectively. In our series, we correctly identified the internal opening in almost 95% of patients with primary fistulas, which is in agreement with the results of Cho (18) and Navarro-Luna et al. (8). In the case of recurrent fistulas, this percentage decreased to 81%. This variation in the results may in part be due to the differences in quality and frequency of the ultrasonography probes used, the type of fistulas included in each of the series and the application of different criteria to locate the internal opening. We used both direct and indirect criteria (18), and also bore in mind the importance of the learning curve when performing anal ultrasonograpy.

The anatomic extension of a complex fistula, which includes accessory septic cavities, secondary fistula tracks, many of which are blind, and horseshoe abscesses is yet another problem in the pre-operative diagnosis of perianal septic pathology. Some authors point out the limitations of ultrasonography for detecting a supraelevated extension and even pathology of the ischiorectal fossa (10), especially in patients with recurrent fistulas in whom there is also scar tissue (19) and alterations in sphincteric musculature. In our series, ultrasonography gave the poorest results in localization of accessory septic cavities in recurrent patients (reliability of almost 69%), but even so, it was still more accurate than physical examination in diagnosing this condition. We believe that some of these cases, particularly patients with more than two recurrences, may benefit from NMR, which has been shown to be more accurate than ultrasonography in the study of the extension of complex anal fistulas (14). However, its high cost, limited availability and lack of studies comparing the diagnostic accuracy of the different techniques (endocoil, body coil, etc.) make ultrasonography the diagnostic procedure of choice in most Coloproctology Units. In addition, it may be done by the surgeon who will perform the operation, in his surgery with very little or no discomfort for the patient. With regard to the other parameters studied in our series, the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography reached between 80 and 95%, similar to that found in most of the published series.

Another point to mention about ultrasonography is the possibility of performing a complementary vaginal study in women in whom there is suspicion of obstetric trauma. Vaginal endosonography enables a more exact evaluation of the anal canal structures to be made since they are not distorted by insertion of a probe (20). More accurate data are obtained on the thickness and integrity of the sphincter complex and rectovaginal wall, as well as of the puborectal muscle. According to Poen et al., diagnostic performance may increase by as much as 25% in cases of faecal incontinence and perianal sepsis (21), and is especially indicated in multiparous women with recurrent septic conditions or fistula tracks located in the rectovaginal wall. However, other studies demonstrate the technical difficulties involved in obtaining adequate images of the anal canal via the endovaginal route due to the impossibility of making adequate contact between the probe and posterior vaginal wall (22), and recommend the use of this complementary route only when there is doubt as to the integrity of the anterior wall of the anal duct.

In conclusion, anal ultrasonography is a very useful diagnostic examination in the study of complex anal fistulas, which complements physical examination. Its diagnostic accuracy is greater than that of the latter, thus enabling surgery to be planned better. The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography does not significantly decrease in recurrent complex fistulas as compared with primary fistulas.

References

1. Beynon J, Mortensen NM, Channer JL, Rigby H. Rectal endosonography accurately predicts depth of penetration in rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 1992; 7: 4-7. [ Links ]

2. Cuesta MA, Meijer S, Derksen EJ, Boutkan H, Meuwissen SG. Anal sphincter imaging in fecal incontinence using endosonography. Dis Colon Rectum 1992; 35: 59-63. [ Links ]

3. Deen KI, Williams JG, Hutchinson R, Keighley MR, Kumar D. Fistulas in ano: endoanal ultrasonographic assessment assists decision making for surgery. Gut 1994; 35: 554-8. [ Links ]

4. Lindsey I, Humphreys MM, George BD, Mortensen NJ. The role of anal ultrasound in the management of anal fistulas. Colorectal Dis 2002; 4: 118-22. [ Links ]

5. Ratto C, Gentile E, Merico M, Spinazzola C, Mangini G, Sofo L, et al. How can the assessment of fistula in ano be improved? Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 1375-82. [ Links ]

6. Law PL, Bartram CI. Anal endosonography: technique and normal anatomy. Gastrointest Radiol 1989; 14: 349-53. [ Links ]

7. Parks AG, Gordon PH, Hardcastle JD. A classification of fistula-in-ano. Br J Surg 1976; 63: 1-12. [ Links ]

8. Navarro-Luna A, García-Domingo MI, Rius-Macías J, Marco-Molina C. Ultrasound study of anal fistulas with hydrogen peroxide enhancement. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47: 108-14. [ Links ]

9. Pascual Migueláñez I, García-Olmo D, Martínez-Puente MC, Pascual Montero JA. Is routine endoanal ultrasound useful in anal fistulas? Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2005; 97 (5): 323-7. [ Links ]

10. Chew SSB, Yang JL, Newstead GL, Douglas PR. Anal fistula: Levovist,-enhanced endoanal ultrasound. A pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum 2003; 46: 377-84. [ Links ]

11. Kuijpers HC, Schulpen T. Fistulography for fitula-in-ano: is it useful? Dis Colon Rectum 1985; 28: 103-4. [ Links ]

12. Schratter SA, Lochs H, Vogelsang H, Schurawitzki H, Herold C, Schratter M. Endoscopic ultrasonography versus computed tomography in the differential diagnosis of perianorectal complications in Crohn's disease. Endoscopy 1993; 25: 582-6. [ Links ]

13. Lunniss PJ, Barker PG, Sultan AH, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 1994; 37: 708-18. [ Links ]

14. Buchanan GN, Halligan S, Bartram CI, Williams AB, Tarroni D, Cohen CRG. Clinical examination, endosonography and MR imaging in preoperative assessment of fistula in ano: comparison with outcome-based reference standard. Radiology 2004; 233: 674-81. [ Links ]

15. Cheong DM, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD, Jagelman DG. Anal endosonography for recurrent anal fistulas: image enhancement with hydrogen peroxide. Dis Colon Rectum 1993; 36: 1158-60. [ Links ]

16. Poen AC, Felt-Bersma RJ, Eijsbouts QA, Cuesta MA, Meuwissen SG. Hydrogen peroxide enhanced transanal ultrasound in the assessment of fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 1998; 41: 1147-52. [ Links ]

17. Ortiz H, Marzo J, Jiménez G, De Miguel M. Accuracy of hydrogen peroxide-enhanced ultrasound in the identification of internal openings of anal fistulas. Colorectal Dis 2002; 4: 280-3. [ Links ]

18. Cho DY. Endosonographic criteria for an internal opening of fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 1999; 42: 515-8. [ Links ]

19. Law PJ, Talbot RW, Bartram CI, Northhover JMA. Anal endosonography in the evaluation of perianal sepsis and fistula-in-ano. Br J Surg 1989; 76: 752-5. [ Links ]

20. Sultan AH, Loder PB, Bartram CI, Kamm MA, Hudson CN. Vaginal endosonography. New approach to image the undisturbed anal sphincter. Dis Colon Rectum 1994; 37: 1296-9. [ Links ]

21. Poen AC, Felt-Bersma RJF, Cuesta MA, Meuwissen SGM. Vaginal endosonography of the anal sphincter complex is important in the assessment of faecal incontinence and perianal sepsis. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 359-63. [ Links ]

22. Ramírez JM, Aguililla V, Martínez M, Gracia JA. The utility of endovaginal sonography in the evaluation of fecal incontinence. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2005; 97 (5): 317-22. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ana María Fernández Frías.

Servicio de Cirugía General y del Aparato Digestivo.

Hospital General Universitario de Elche.

Camí de l`Almazara, s/n.

03202 Elche (Alicante).

Fax: 966 679 377.

E-mail: ferfri2002@yahoo.es

Recibido: 04-11-05

Aceptado: 02-03-06

texto en

texto en