My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.107 n.5 Madrid May. 2015

ORIGINAL PAPERS

A review of three educational projects using interactive theater to improve physician-patient communication when treating patients with irritable bowel syndrome

Ben Saypol1, Douglas A. Drossman2, Max J. Schmulson3, Carolina Olano4, Albena Halpert5, Ademola Aderoju2 and Lin Chang6

1Theater Delta. Chapel Hill, North Carolina. USA.

2UNC Center for Functional GI and Motility Disorders. Chapel Hill, North Carolina. USA.

3Laboratorio de Hígado, Páncreas y Motilidad (HIPAM). Department of Experimental Medicine. Faculty of Medicine. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Mexico City, Mexico.

4Universidad de la República. Montevideo, Uruguay. Clínica de Gastroenterología "Prof. Henry Cohen".

5Section of Gastroenterology. Boston University School of Medicine. Massachusetts, USA.

6Oppenheimer Family Center for Neurobiology of Stress Director. Digestive Health and Nutrition Clinic David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. California, USA

Research site: Research was conducted at the UNC Center for Functional GI and Motility Disorders and the UNC School of Medicine (both in Chapel Hill, NC), as well as two medical conferences (named in the article).

ABSTRACT

Background: Quality communication skills and increased multicultural sensitivity are universal goals, yet teaching them have remained a challenge for educators.

Objective: To document the process and participant responses to Interactive Theater when used as a method to teach physician-patient communication and cross-cultural competency.

Design, setting, and participants: Three projects are reported. They were collaborations between Theater Delta, the UNC Center for Functional GI and Motility Disorders, the Rome Foundation, the World Gastroenterology Organization, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Outcome measures: 8 forced choice and 6 open ended were collected from each participant using a post-performance evaluation form.

Results: Responses to the 8 indicators relating to a positive experience participating in the Interactive Theater. The vast majority either agreed or strongly agreed with the statements on the evaluation form. Written comments explained why.

Conclusions: Data indicates that Interactive Theater stimulates constructive dialogue, analysis, solutions, and intended behavior change with regard to communication skills and adapting to patients from multicultural backgrounds. Interactive Theater directly focuses on communication itself (active listening, empathy, recognizing cultural differences, etc.) and shows promise as an effective way to improve awareness and skills around these issues.

Key words: Communication skills. Learning outcomes. Ethics/attitudes. Cross-cultural communication. Best evidence medical education. Management. Teaching and learning. Simulation, Theater, training.

Introduction

Teaching health care providers, fellows, residents, and medical students communication skills and multicultural sensitivity are growing priorities in healthcare education; yet they remain difficult to implement. Studies have shown that good communication skills are associated with increased provider and patient satisfaction, adherence to treatment, reduction in malpractice suits, and positive health outcomes (1). However, pressures in the health care system to see more patients in less time and generate more procedures tend to compromise the value of these skills to learners; they becomes less of a priority (2).

Traditionally communication skills have been taught in a limited fashion through lectures, videos, and small group discussions. But the personal experience of interacting with the patient is limited with these non-interactive modalities.

Since the 1980's, the use of standardized or simulated patients gained acceptance as standard practice, allowing for one-on-one learning within the training curricula (3). This practice involves physicians or medical students engaging in a role play with actors who have been trained to simulate the symptoms and behaviors of typical patients (4).

This study introduces Interactive Theater (IT) as another viable method for teaching physician-patient communication and cultural competence. IT is a burgeoning educational tool that has had positive impact around numerous issues in a wide variety of communities. This includes diversity issues with university faculty (5,6) and medical school faculty (7), sexual assault education with undergraduate students (8), and HIV and other reproductive health issues with teens in communities in developing nations (9). One advantage of IT is that the role play simulation can be done with a large audience thus permitting group learning around core concepts in communication.

IT consists of three parts: 1. A scripted scene that captures the key learning elements; the scene is based on comprehensive research and analysis of real clinical interactions; 2. An opportunity for audience members to interact with the characters; actors remain in their roles as simulated physicians and patients throughout; and 3. A facilitated conversation, where audience members share their reactions to the scene and the interaction, identify of the main issues or problems, and offer solutions for improving the communication (10). Solutions can be demonstrated by soliciting audience volunteers or coaching the character (actor remain in role). While the role playing found in standardized patient work can be useful, the IT approach takes full advantage of theater's role as a medium through which communities -in this case physicians and medical professionals- can observe, analyze, and improve themselves and their skills.

This study demonstrates this educational approach mostly using a patient having irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a common medical condition. IBS is a functional bowel disorder in which abdominal pain or discomfort is associated with changes in bowel habit (11). The following symptoms may occur in combination: Abdominal pain and discomfort, bloating and/or distension, and disordered defecation include diarrhea, constipation or mixed bowel habit (11). The diagnosis and care of patients with IBS patients can be challenging because of the limited knowledge of the disease pathogenesis, limited successful treatments for a chronic disorder, and a low confidence in the available therapeutic options (12). In addition because there is no clear diagnostic marker there may be physician uncertainty about the diagnosis and communication difficulties between doctors and patients particularly if patients feel stigmatized having a "functional" disorder (13). Therefore, IBS provides a good example in which communication skills and the building of a strong doctor-patient relationship are paramount.

Aims

Three projects were conducted, all with the common aim to use IT to improve physician-patient communication using a patient centered approach. Efforts were made to obtain qualitative data as to the impact of this activity on the learners. The specific programs of IT were designed to: a) to develop and implement a facilitative style of communication, including active listening skills; b) to increase the expression of empathy toward the patient; c) to clarify and accept the patient's perspective on each issue and engage in a conversation to reach a common understanding and set of goals; d) to learn to acknowledge and manage one's own emotions in the clinic; and e) to increase cultural sensitivity and competency.

Methods

IT was performed at several locations and the formats were modified to achieve the specific learning needs of the audience.

Project #1 - Interactive Theater Performances for the UNC Center for Functional Gastrointestinal and Motility Disorders

The first IT project was conducted in North Carolina by Dr. Douglas Drossman, MD, and Dr. Ben Saypol, PhD, representing the UNC Center for Functional Gastrointestinal and Motility Disorders and Theater Delta, respectively. Dr. Drossman is an expert on functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) and the teaching of communication skills and Dr. Saypol is an expert on IT who conducts performances and workshops nationally and internationally. This project, focusing on the tertiary care of IBS, was performed for a team of physicians, fellows, interns and residents at a monthly evening seminars on physician-patient communication.

The IT model for this first performance consisted of four parts: A scripted scene, the audience interaction, the facilitated conversation, and an image theater exercise focusing on cultural issues.

The scene simulated a visit at the GI clinic at UNC Hospital. Dr. Matthew Moore, a 45 year old white male Gastroenterologist interviews Mrs. Tess Wilson, a 45 year old African American woman from a small town in North Carolina. Ms. Wilson, who arrived 30 minutes late due to car trouble, has been suffering from constipation, bloating, and abdominal pain for the last 2.5 years, has been to 3 other doctors, and is frustrated with her care. Dr. Moore speaks rapidly, and focuses on information gathering. He seems a bit distant and dismissive. And, as she gets emotional, he closes off even further. In the end he orders a colonoscopy (although she had one 3 years ago) and an upper endoscopy.

Next, the audience asks the characters -actors remaining in role- questions about their attitudes and behaviors during the medical interview. Two issues emerged, both of which affected Dr. Moore's behavior during the interview. The first was a subtle negative toward a woman of less educational attainment and a different race. The other was personal feelings of insecurity in his role as a physician. After the questions and answers, audience members engaged in constructive, respectful dialogue, led by the facilitator. Facilitator asked questions (e.g. what did you notice? What was the impact? What could be done differently?), highlighted key ideas/themes/solutions, and shared relevant information with regard to the aims noted above.

Finally, the facilitator led audience members through an Image Theater exercise and discussion focusing on cultural identities. The actors first struck a familiar frozen image from the scene to remind the audience of what they saw; then the actors changed roles within the image creating a new image. The African American female patient donned the white coat and took the Doctor's chair, and the white male doctor removed his white coat and sat in the patient's chair. Audience members discussed their immediate reactions as to how they thought the new cultural identities (gender and race) would impact the same physician-patient interaction.

Project #2 - Interactive Theater Performances for the UNC School of Medicine

The second project involved 2nd year medical students at the UNC School of Medicine who were about to begin their clinical rotations. This project, focusing on medical residency care in the inpatient hospital setting, was performed twice, for each half of the second year cohort of medical students. The model for this project was similar to project one but with a scripted inpatient scene, as well as the addition of an onstage audience intervention.

The audience is introduced to Dr. Kimberly Adams, a 30 year old female 1st year resident, who is pre-rounding on her nine patients in the early morning, and Jim Richardson, a 42 year old African American male patient who was admitted through the emergency room to the hospital the night before with black tarry stools and anemia. Dr. Adams' behavior reflects a hurried style where she collects and confirms information rapidly, focusing on what seems to be a pre-determined group of questions and some medical jargon. Jim seems frustrated. He has been woken up after a night of little sleep, is being directed not to eat due to his pending diagnostic studies, and feels he is repeating the same personal medical information to doctors over and over. There is little engagement between the two, and Dr. Adams does not provide much understanding or empathy for Mr. Richardson's situation. The tension in the scene heightens when Jim seeks reassurance that cancer is not the source of the black stools, which was determined to be a gastrointestinal bleed. By that time, however, communication has broken down, and Dr. Adams seems unable to provide the comfort he seeks. She focuses more on the diagnostic tasks to be done for the day such as obtaining written permission for the endoscopic procedure.

Like the previous project, after the simulation, the audience members were able to ask the characters questions as to what they did in the scene and why. This was followed by a facilitated discussion of reactions, issues, and possible solutions. However, for this project, after solutions to improve the interaction were offered, facilitators introduced the technique of the "On Stage Intervention." One medical student in the audience volunteered to go on stage, replace the doctor, and try an alternative communication strategy with the patient, according to the ideas and suggestions raised in the facilitated discussion. In turn, another dialogue was facilitated as to what strategies and/or techniques the audience members tried that were successful when compared to the first simulation.

Finally, the facilitator repeated the image theater exercise outlined above. The African American male patient got out of the hospital bed and donned the white coat, and the white female doctor removed her white coat and got in the hospital bed. Audience members had a dialogue about how they thought the new cultural identities (gender and race) would impact the same physician-patient scene.

Project #3 - The Cross Cultural Communication Workshop at "IBS - The Global Perspective" and the "American Gastroenterological Association Communication Skills Workshop"

This third project was developed for an international audience emphasizing a cross-cultural focus in the care of patients with IBS. The model was applied in a workshop at the IBS - The Global Perspective Conference, an international symposium sponsored by the Rome Foundation and the World Gastroenterology Organization. This meeting's objective was to offer global picture of IBS both in terms of the epidemiology and ethnic and cultural differences; and secondly to address the importance of the development of cross-cultural clinical and research competencies (14). Additionally, this workshop was held a second time at a Rome Foundation-American Gastroenterological Association Communication Skills Workshop titled, "Improving the Medical Interview and the Physician Patient Relationship with Patients Having Functional GI Disorders," held June 8-9, 2012 in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

These workshops presented three interactive vignettes, each with a similar clinical case of IBS with diarrhea, though the patient role was modified for each performance to reflect cultural components of the illness presentation. There was a physician from the USA who interviewed a Nigerian, Mexican, and Russian IBS patient, respectively. To add a greater perspective to the role, the patient simulators were played by practicing gastroenterologists who had their respective first or second generation ethnic background. The case simulation was appropriately modified by these same physicians to match the anticipated cultural origin of them as the patient. The audience consisted of clinical scientists and clinicians with an interest in FGIDs from various areas of the world including the U.S., Latin America, Europe, Asia, and Israel.

As mentioned, IT is a flexible format with many tools. This model had shorter vignettes, as well as less audience/character interaction offset by increased dialogue among participants. Table I summarizes the key cultural features for each patient that were addressed.

Results

Projects #1 and #2 (Interactive Theater Performances for the UNC Center for Functional Gastrointestinal and Motility Disorders and the UNC School of Medicine)

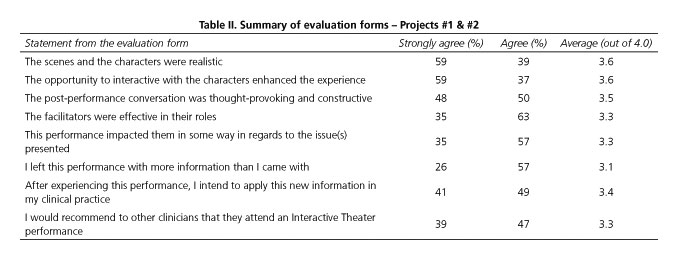

Evaluation forms (n = 170) were distributed and collected at the end of each performance and the data were compiled and analyzed. Responses to the questions used a 4-point Likert scale: 4 = strongly agree, 3 = agree, 2= disagree, and 1= strongly disagree (excluding the item "neither agree nor disagree" in order to allow for a forced-choice response). As shown in table II, the responses were overall positive with regard to the realism of the scenario, the interactive format, the post-performance conversation, and the facilitation. In addition, the data indicate notable impact on audience members, with the intention to apply the knowledge and skills to their clinical practice.

Some examples of the qualitative responses that support the learners' intent to apply this knowledge include:

- "I can see myself in the doctor role, making some of the same mistakes in the future. This helps me think about how I might deal with the same situation."

- "I intend to be more consistent about merging agendas."

- "I try to be as empathetic as possible, but I also tend to let stress impact my demeanor and this showed how important it is to remain calm."

- "It's nice to have a visual reminder (and experience) that I can still manage to be an empathetic resident one day, even with a full load of patients- because that is a worry."

Project #3 - The Cross Cultural Communication Workshop at "IBS - The Global Perspective" and the "American Gastroenterological Association Communication Skills Workshop"

A formal evaluation was not conducted for cross-cultural workshop at the IBS: A Global Perspective conference in Milwaukee. During the session, however a white board was used to compile, in an open ended fashion, the learning points that were obtained by the participants.

The themes were:

- Increase active listening.

- Increase empathy.

- Be attuned to non-verbal communications between doctor and patient.

- Consider that a few small changes in technique can make important differences.

The specifically articulated strategies for improvement were:

- When there are differences in view say "yes, and" instead of "yes, but."

- When possible learn in advance characteristics of patients from other cultures (e.g. communication styles -verbal and non-verbal-, beliefs, priorities, etc.).

- Manage personal behaviors and emotions when differences in opinions occur.

- Avoid dismissing or diminishing patient views and attitudes.

- Increase awareness and exploration of psycho-social issues -specifically ones that arise from the patient's unique culture.

An evaluation form was distributed and collected at the similar program done at the American Gastroenterological Association Communication Skills Workshop in North Carolina. The data was compiled and analyzed. This summary of the quantitative data, as seen in table III is based on the data in the evaluation forms (n = 6) with the following Likert scale: 5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 2 = disagree, and 1 = strongly disagree. Similar to the results for projects 1 and 2, the data reveals and extremely positive response from audience members to the realism of the scenario, the interactive format, the post-performance conversation, and the facilitation. In addition, the data indicate positive impact in terms of the intention to apply the knowledge and skills to their clinical practice.

Written comments which supported intent to change personal behaviors in care include:

- "I intend to be respectful of other cultures, and avoid my own cultural biases."

- "Use more questions to obtain information about beliefs that may be uncommon in America (praying/ spiritual)."

- "I was impacted by the importance of empathy, introductions, and respect."

Discussion

IBS produces a high economic burden in term of direct and indirect costs. Proposed strategies to reduce these expenses include physician and patient education, support groups, early consideration of psychological issues and treatment, avoidance of unnecessary investigations and optimizing the physician-patient relationship (15). Communication skills development is considered an essential prerequisite to learn how to understand patient cognitions and acquire and exhibit empathic behavior in clinical practice (16), especially when treating patients with chronic and debilitating disorders such as IBS. Physicians, fellows, residents, and medical students, however, usually don't receive adequate training in communications skills to improve such relationship, especially with regards to teaching empathy and how to maintain a long term physician-patient relationship (17). Thus we used this disorder as a model to apply IT methods to help providers and trainees learn the skills necessary to develop an effective physician-patient relationship.

It has been proposed that improving communication skills is a critical task for medical training programs, postgraduate courses and all types on continuing medical educational programs, professional organizations and societies (18). One method for achieving these skills is Standardized Patient Education, using trained actors to portray patients and family members, involving learners in improvised case scenarios (19). In the current paper, we have described the experience with a new performance-based methodology IT to improve communication skills and cultural competency. Three projects were developed. The first was developed for GI physicians in different levels of training in a seminar and was directed towards improving physician-communication skills. The second was designed for medical students as part of their educational curriculum on physician-patient communication. And the third was a workshop held at two international conferences on FGIDs, co-organized by two international gastroenterological organizations focusing on cross-cultural communication for IBS. The data reveals that all three projects were successful in terms of having an immediate positive and thought-provoking impact on audience members. The formal evaluations showed a very positive response of the audience members, evidenced by their expression that the workshop had a significant impact on them and that they intended to apply the ideas gained into their future practice. It goes without saying that it is not possible to measure the degree of overall success of these types of theater based trainings until more comprehensive data is gathered, including indicators of patient and provider satisfaction, adherence to treatment, and positive health outcomes.

In addition, scenarios and learning outcomes around cultural competency were present in all of the projects. Achieving cultural competence is necessary in the care of patients who are members of an ethnic or racial minority. Eiser and Ellis (20) consider that this process involves specific cultural knowledge, skills and attitude adjustments. These issues include awareness of information such as the influences of religion on health, differing paradigms for illness, the use of home remedies, distrust, racial concordance and discordance and health literacy (20). The last one, defined as the ability of understanding and act on health information, is essential for high quality care (21).

In conclusion, IT can be an effective tool for improving physician-patient communication and cultural competency. Much like projects were developed for primary care in medical schools and for tertiary care that focus on GI issues, performances could be developed for other sub-fields of medicine. Scenes could be developed on the communication around prevalent diseases like hypertension and diabetes, as well as to explore complex medical conditions like chronic pain. And these scenes could be used with more experienced physicians or for medical students just starting out. IT is fully customizable to the topic and audience.

In addition, one could use this medium for patient education and advocacy. At the time of submission of this article, the primary authors (BS, DD) were working on a project to use IT to improve educate patients on how to better communicate with their doctor, improve their healthcare experience, and enjoy better patient outcomes. Learning outcomes include: preparing for your appointment, modifying expectations to include playing an active role in one's own healthcare, and communicating better with your physician.

As IT is used more, it will be critical to develop more sophisticated evaluation tools to measure specific impact and change. First, evaluators should strive to measure physician knowledge/attitudes both pre-performance and post-performance, as well as gather longitudinal data measuring the impact of the performances over time (e.g. three months, six months, and/or 1 year after the performance). Second, practitioners must develop a better set of indicators to use with audience members. Possibilities include those that measure patient and provider satisfaction, patient adherence to treatment, and positive health outcomes.

References

1. Roter DL, Hall JA. Doctors talking with patients/ Patients talking with doctors: Improving communication in medical visits. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group; 1992. [ Links ]

2. Brownlee S. (2012, April 16). The doctor will see you - If you're quick. Newsweek 2012:17:46-50. [ Links ]

3. Stillman PL, Swanson DB, Smee S, et. al. Assessing clinical skills of residents with standardized patients. Ann Internl Med 1986;105: 762-71. [ Links ]

4. Stillman PL, Regan MB, Philbin M, et al. Results of a survey on the use of standardized patients to teach and evaluate clinical skills. Acad Med 1990;65:288-92. [ Links ]

5. Kaplan M, Cook C, Steiger J. Using Theatre to Stage Instructional and Organizational Transformation. Change, The Magazine of Higher Learning. 2006 May/June: 33-39. [ Links ]

6. Kumagai AK, White CB, Ross PT, et al. Use of Interactive Theater for Faculty Development in Multicultural Medical Education. Med Teach 2007;29:335-40. [ Links ]

7. Agogino AM, Ng E, Trujillo C. Using Interactive Theater to Enhance Classroom Climate. Proceedings of the 2001 NAMEPA/WEPAN Joint National Conference: "Co-Champions for Diversity in Engineering." WEPAN/NAMEPA; 2001 Apr. 21-24; Alexandria, VA. Champaign, IL: Stipes Publishing L.L.C .; c2001; 67-1. [ Links ]

8. Rodriguez JI, Rich MD, Hastings R, et al. Assessing the Impact of Augusto Boal's 'Proactive Performance': An Embodied Approach for Cultivating Prosocial Responses to Sexual Assault. Text and Performance Quarterly 2006;26:229-52. [ Links ]

9. Sohail S. Interactive theatre for HIV/AIDS side effects on youth sexuality reproductive health and rights in Pakistan to learn and practice. Retrovirology 2010;7(Supl.1):69. [ Links ]

10. Saypol B. Effective Practices for Establishing an Interactive Theatre Program in a University Community (dissertation). (Boulder): University of Colorado at Boulder; 2011 252 p. Retrieved from ProQuest. (Order No. 3453786). [ Links ]

11. Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480-91. [ Links ]

12. Siproudhis L, Delvaux M, Chaussade S, et al. Patient-doctor relationship in the irritable bowel syndrome. Results of a French prospective study on the influence of the functional origin of the complaints. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2002;26:1125-233. [ Links ]

13. Drossman DA. Functional GI Disorders: What's in a name? Gastroenterology 2005;128:1771-2. [ Links ]

14. Quigley EM, Sperber AD, Drossman DA. WGO - Rome Foundation Joint Symposium Summary: IBS-The Global Perspective. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011;45:i-ii. [ Links ]

15. Camilleri M, Williams DE. Economic burden of irritable bowel syndrome: Proposed strategies to control expenditures. Pharmacoeconomics 2000;17:331-8. [ Links ]

16. van Dulmen AM, Fennis JF, Mokkink HG, et al. The relationship between complaint-related cognitions in referred patients with irritable bowel syndrome and subsequent health care seeking behavior in primary care. Fam Pract 1996;13:12-7. [ Links ]

17. Klitzman R. Improving education on doctor-patient relationships and communication: Lessons from doctors who become patients. Acad Med 2006;81:447-553. [ Links ]

18. Gadacz TR. A changing culture in interpersonal and communication skills. Am Surg 2003;69:453-8. [ Links ]

19. Browning DM, Meyer EC, Truog RD, et al. Difficult conversations in health care: Cultivating relational learning to address the hidden curriculum. Acad Med 2007;82:905-13. [ Links ]

20. Eiser AR, Ellis G. Viewpoint: Cultural competence and the African American experience with health care: The case for specific content in cross-cultural education. Acad Med 2007;82:176-83. [ Links ]

21. Williams MV. Recognizing and overcoming inadequate health literacy, a barrier to care. Cleve Clin J Med 2002;69:415-8. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ben Saypol.

Theater Delta.

Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

USA

e-mail:

bsaypol@gmail.com

Received: 18-12-2014

Accepted: 22-01-2015