Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.107 no.5 Madrid may. 2015

SPECIAL ARTICLE

Management of antithrombotic drugs in association with endoscopic procedures*

Manejo de los fármacos antitrombóticos asociados a los procedimientos endoscópicos

Fernando Alberca-de-las-Parras1, Francisco Marín2, Vanessa Roldán-Schilling3 and Fernando Carballo-Álvarez1

1Unit of Digestive Diseases and 2Department of Cardiology. Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca. IMIB. Murcia, Spain.

3Department of Hematology and Oncology. Hospital Universitario Morales Meseguer. Murcia, Spain

* Guidelines endorsed by the Working Group of Thrombosis of Spanish Cardiology Society (GTCV-SEC), Spanish Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (SEED), Spanish Society of Digestive Diseases (SEPD) and Spanish Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis.

ABSTRACT

The use of antithrombotic drugs (anticoagulants and antiplatelets) has increased significantly with our understanding of cardiovascular risk. Encountering patients on these therapies who require an endoscopic procedure is therefore increasingly common. At decision making the endoscopist must rely on other specialists (basically cardiologists and hematologists) as risk not only lies among increased bleeding odds but also in the possibility of thrombosis following dose discontinuation or change. Understanding the pharmacology, indications, and risks of endoscopic procedures is therefore essential if sound decisions are to be made. The efforts of four scientific societies have been brought together to provide clinical answers on the use of antiplatelets and anticoagulants, as well as action algorithms and a practical protocol proposal for endoscopy units.

Key words: Antithrombotic drugs. Antiplatelets. Anticoagulants. Endoscopic procedures.

RESUMEN

Los fármacos antitrombóticos (anticoagulantes y antiagregantes) han experimentado un importante incremento de su uso derivado de los conocimientos sobre el riesgo cardiovascular. Por ello, es cada vez más frecuente encontrarnos con pacientes con estos tratamientos a los que hay que realizar procedimientos endoscópicos. En el acto de la toma de decisiones el endoscopista debe apoyarse en otros especialistas (básicamente cardiólogos y hematólogos) pues el riesgo no sólo se encuentra en las posibilidades aumentadas de sangrado, sino también en la posibilidad de trombosis ante la suspensión o variación de las dosis de dichos fármacos. Por ello es esencial conocer su farmacología, sus indicaciones y el riesgo de los procedimientos endoscópicos para poder tomar decisiones correctas. Se han aunado los esfuerzos de cuatro sociedades científicas para aportar respuestas clínicas con respecto al uso de antiagregantes y anticoagulantes, elaborando algoritmos de actuación, así como una propuesta práctica de un protocolo para las unidades de endoscopia.

Palabras clave: Fármacos antitrombóticos. Antiagregantes. Anticoagulantes. Procedimientos endoscópicos.

Introduction

For many years single or dual anticoagulation and antiaggregation have become a therapeutic and preventive tool, particularly regarding highly prevalent cardiovascular diseases. This, together with increased interventionism among endoscopic techniques, represents a higher risk. However, such risk is not only derived from potential bleeding but also from thrombotic risk (1), its obviation by endoscopists being unacceptable.

Scientific societies have issued a number of guidelines and recommendations for such situations (2-8) and compliance with them have even brought about secondary benefits in terms of both financial savings and thrombosis incidence (9).

A first Spanish version of these guidelines was published in 2010 (6). However, the emergence of new drugs and of significant data in the literature has prompted a revised and updated version, for which the consensus of the Working Group of Thrombosis of Spanish Cardiology Society (GTCV-SEC) and the Spanish Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis.

An analysis of the scarce adherence to guidelines and of their applicability (10,11) suggests that less academic, more practical guidelines should be developed, since the criteria for early drug re-introduction are approached by cardiologists (12), which conditions follow-up by gastroenterologists for fear of early bleeding.

The goal of the present paper is to summarize the available evidence, and to discuss newly marketed medications using a clinical questions and answers approach to help gastroenterologists in their decision-making.

What management would be appropriate for acute gi bleeding in patients on anticoagulants or antiplatelets?

As is usual in medical practice, decision making depends upon risk and severity. In patients with high thrombotic risk (for example, with mitral prosthesis) and mild bleeding anticoagulation withdrawal is inappropriate-pharmacological and endoscopic measures may be considered while leaving reversal aside.

In general, anticoagulants must be discontinued immediately for severe bleeding. In the absence of severity criteria the approach should hinge upon the patient's thrombotic risk, and the following therapies may be initiated, whether sequentially or in parallel with the resolutive endoscopic technique (3,13) (Fig. 1).

1. Vitamin K1, IV (phytomenadione), 10 mg (one ampoule) in 100 ml of saline or 5% glucose solution: 10 ml over 10 minutes (1 mg/10 min), the rest in 30 minutes. The effect begins within 6 hours and lasts for 12 hours.

2. Fresh plasma, 10 to 30 ml/kg; it may be repeated in halved dose after 6 hours, as factors have a half-life of 5-8 hours. Currently, guidelines do not recommend the use of fresh plasma to reverse anticoagulation except when it is the only measure available, nor is this therapy accepted for plasma expansion.

3. Prothrombin complex concentrate containing factor IX ((BERIPLEX 500 IU®, OPTAPLEX®, PROTHROMPLEX IMMUNO TIM 4 600 IU®): Equivalent to 500 ml of plasma. Dosage is estimated using the following formula: (Desired prothrombin time - obtained prothrombin time) x kg weight x 0.6. It may be thrombogenic.

4. Recombinant activated factor VII (Novoseven®): 90 µg/kg in slow bolus (2-ml ampoule = 1.2 mg). Effects are seen at 10 to 30 minutes after dosing, and last 12 hours. It normalizes prothrombin time and fixes platelet malfunction. It is highly thrombogenic, and its use is currently indicated in hemophiliacs with inhibitor, acquired hemophilia, and severe congenital FVII deficiencies only. The latter two drugs may not be administered together.

These measures will be applied until the INR becomes stable between 1.5 and 2.5, and bleeding stops.

The bleeding risk of patients on anticoagulants is 6.5-fold higher than in those off these drugs (14).

From a practical standpoint, and in the emergency setting, the right thing to do is to initially use a prothrombin complex concentrate, which is the fastest option to achieve reversal.

The approach modestly changes with the new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) as neither vitamin K nor fresh plasma have proven effective (15). Attitude will logically depend on bleeding severity, paying particular attention to renal function especially in patients on dabigatran, as it prolongs its anticoagulating action. This is also the case with apixaban and rivaroxaban in hepatocellular dysfunction.

Antiplatelets and NSAID discontinuation will not alter the natural history as effects on hemostasis will linger for a few days; however, we should bear this in mind for lesions that predictably will not heal fast. The fact that aspirin and NSAIDs may also be a cause of bleeding is not to be forgotten. Their effect may, nevertheless, be partly reversed with fresh platelet transfusions when advisable according to bleeding severity.

What coagulation changes should be considered before endoscopy and how can they be corrected? (Table I)

In extreme situations (fewer than 10,000 platelets, INR higher than 6, etc.) with active bleeding, we must correct such changes before the endoscopic technique, as this may stop the bleeding and render the technique -and its potential complications- unnecessary.

In patients with thrombocytopenia our attitude will depend on procedure type: for high-risk procedures platelet count must be higher than 50,000/μl; for low-risk procedures a platelet count > 20,000/μl is acceptable. Platelet deficiency is corrected on a schedule using infusions during the technique and immediately before it. It suffices with increasing platelet numbers to 40,000-50,000/mm3. Each platelet unit increases the count by 5,000-10,000 per mm3, and the dose is 1 U/10 kg of body weight. In case of platelet refractoriness with severe bleeding evidence the use of recombinant activated factor VIl (rVlla) (Novoseven®) is recommended, with hemostatic action in patients with severe thrombocytopenia and thrombocyte disease, at a dose of 90 to 150 µg/kg every two hours intravenously until bleeding resolution.

Prothrombine activity lower than 50% (vs. INR > 1.4) is usually found in chronic liver disease, factor VII and X deficiencies, and oral anticoagulation. In such case the above schemes are used for anticoagulated patients. Generally speaking, only severe FVII and FX deficiencies need correction (< 10%).

Activated partial prothrombin time (APTT) is measured as an extension of PT. It may be seen in the (decreasing) use of heparin sodium i.v. and in some patients with LMWH. As regards heparin sodium APTT becomes normal after discontinuation within 4 to 6 hours. However, should faster reversal be desirable in an emergency setting, protamine sulphate is to be used. As for LMWH, the effect usually clears within 12-24 h, and APTT normalization may take slightly longer. In the case of LMWH protamine is of limited help. APTT prolongation may also be seen in factor deficiencies (hemophilia A/B/C), and in the presence of lupus anticoagulants.

What endoscopic techniques are considered to be associated with a higher bleeding risk?

Bleeding risk has been stratified by expert consensus, as indicated in clinical guidelines (2) and manuals, into two risk levels (Table II). Basically agreeing with this classification, we may importantly increase risk stratification, as an endoscopic sphincterotomy in a patients with multiple conditions is clearly unlike the excision of a pedicled polyp. It is therefore important that the endoscopist's view be taken into account particularly after the procedure when considering antiplatelets/anticoagulant reintroduction times.

- Colonoscopy: This is a technique that in itself does not increase bleeding risk in patients with coagulation issues.

- Biopsy: Bleeding risk during biopsy taking is extremely rare, approximately 1‰ (16).

- Polypectomy: Polypectomy-related major bleeding risk in several extensive series oscillates between 0.05% and 1%, but it may be up to 4.3% for polyps greater than 1 cm, and 6.7% for those larger than 2 cm (17-19). This risk seemingly increases for polyp sizes above 2 cm, and pedunculated polyps have been seen to bleed more severely than sessile ones, hence associating a risk-reducing technique such as the use of prophylactic adrenaline, endoloop, and endoclips is advisable for patients with coagulation issues (19).

Two types of bleeding exist: Immediate bleeding when nurturing vessels are improperly coagulated, and delayed bleeding, after 1 to 14 days, which is more serious; this should be considered before antiplatelets reintroduction.

In antiaggregated patients its role for GI bleeding has been poorly analyzed; in an animal study, 7-mm lesions in the colon showed an increase in bleeding time among those on aspirin vs. no therapy (155 seconds vs. 169 seconds - p < 0.05) (20); similarly bleeding has been found to be increased at biopsy sites in patients on aspirin versus controls or NSAIDs (21). However, these experimental studies have found no clinical application in the literature regarding patients undergoing endoscopic procedures.

Aspirin and NSAIDs have not been shown to increase bleeding risk during polypectomies, albeit these are the retrospective or limited-analysis studies on which both the ASGE and Euroean guidelines were based; these guidelines do not recommend antiplatelet discontinuation before endoscopy (22). However, a prospective study amongst them, while not showing increased complications, does find trace amounts of blood in the stools of up to 6.3% of patients versus 2.1% of subjects on placebo (23). The most relevant complication, namely delayed bleeding, was specifically discussed in a case-control study, thus confirming no increased bleeding in the subgroup on aspirin versus placebo; however, the use of aspirin was not studied beyond 3 days following the procedure, and bleeding episodes have been described up to 19 days afterwards (24). Hence, some authors recommend that antiplatelets be discontinued within 4 to 7 days of risky techniques, and reintroduced after 7 days when used as secondary prevention, or 14 days when used as primary prevention, following polypectomy (25).

In anticoagulated patients bleeding risk after polypectomy is increased, even when anticoagulation is discontinued before the procedure (2.6% vs. 0.2%, p = 0.005) (26). In an extensive registry of 120,886 procedures in 95,807 patients bleeding was only identified in 2% of patients having discontinued heparin (27). Another paper only describes 3 bleeding episodes among 225 polypectomies for 123 anticoagulated patients where anticoagulants had been discontinued previously (28). Recently, a paper was reported where polyps smaller than 10 mm were excised in 70 patients on acenocoumarol, which found higher bleeding rates in the group treated with a hot loop versus a cold loop, both regarding early (23% vs. 5.7%) and delayed (14% vs. 0%) bleeding (29).

ERCP and sphincterotomy. The incidence of bleeding falls between 2.5% and 5% (30). Different studies define anticoagulation as a clear risk factor for bleeding. Regarding antiaggregation only two retrospective studies (31,32) have discussed this effect, with inconclusive results as considered in the American Society's clinical guidelines, but with a risk for acute bleeding in one of them (32) of 9.7% vs. 3.9% (ASA vs. controls, p < 0.001), and a risk for delayed bleeding of 6.5% vs. 2.7% (p = 0.04), which suggests that, except for emergency settings, discontinuation is desirable at least 7 days before the technique. Balloon sphincteroplasty has been proposed as an alternative technique for patients in need of urgent bile duct opening and with coagulation disorders (33), as well as in the transient use of biliary prostheses without sphincterotomy.

Enteroscopy. The simple technique seems to pose no risk whatsoever, but should be considered a risky technique when used as a therapeutic, interventional approach, which is the case in up to 64% of cases (34).

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). In a recently reported retrospective paper in patients undergoing 1,166 ESDs delayed bleeding was analyzed, and the use of antithrombotic medications was shown to be an independent risk factor, higher still when two drugs were used (no statistical significance) (36).

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). Several papers exist that retrospectively discuss the role of antithrombotics in this procedure, and fail to detect any increased bleeding risk when aspirin and clopidogrel are used, even concomitantly (36).

Which are the primary antiplatelets available in spain?

Antiplatelets are drugs that act by inhibiting platelet functioning at various levels, as seen in figure 2. Its classification depends on their mechanism of action (Table III).

There is a wide spectrum of actions, and both antiplatelets effects and duration seem to vary for each one of them (Table IV).

A factor for consideration is their association with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which may enhance antiaggregating effects.

The novel ADP receptor blockers are key to the prevention of acute coronary syndrome, mainly following the placement of stents. From a gastroenterologist's standpoint, we should know their antiaggregation effect is immediate and stronger than that of aspirin, and therefore we should discontinue them within 5 to 7 days of a high-risk procedure (37) (Table V).

What are the primary indications of antiplatelets?

As gastroenterologists we must now these indications, as well as the impact that the discontinuation of a properly indicated drug may have for patients (8).

Indications include (38):

- AMI with or without ST elevation: dual antiaggregation (DA), aspirin plus clopidogrel (or prasugrel or ticagrelor), for 12 months.

- Unstable angina or AMI without ST elevation not requiring coronariography: DA for 1 to 12 months.

- Metallic stent placement: DA up to 12 months.

- Antiproliferative drug-sluting stents: DA for 12 months.

- After fibrinolysis (up to 12 months).

- Stable coronary disease: Only aspirin (clopidrogrel in aspirin intolerants).

- Heart disease primary prevention in patients at risk: No DA necessary, only aspirin or clopidogrel, which may be discontinued without risk.

- AMI without reperfusion therapy (at least 1 month, ideally up to 12 months).

- Ischemic stroke associated with large-vessel and small-vessel arteriosclerosis (aspirin, cilostazol or clopidogrel) (39).

What is the risk of discontinuing a properly indicated antiplatelet therapy?

Early dual (aspirin + clopidogrel) antiplatelet therapy discontinuation entails a stent thrombosis risk of 29% (8%-30%) (40). Discontinuing dual antiaggregation after stent implantation increases the risk for potentially-lethal subacute stent thrombosis by 15% to 45% within a month. In the secondary prophylaxis of AMI risk is higher (3-fold) for discontinuation within 14 days. Risk also increases within 3 days of balloon angioplasty (41).

Are all antiplatelets alike in antipletelet power and secondary bleeding risk? Do all antiplatelets doses behave the same way?

Aspirin does not contraindicate any diagnostic or therapeutic procedure (7).

No differences have been found between aspirin 100 mg and 300 mg in antiplatelet power; only aspirin 300 mg in three daily 100 mg doses has a somewhat higher antiplatelet strength, hence no differential management is warranted for patients according to their dosage (42).

No prospective, randomized studies in the non-cardiac surgery setting have been carried out to assess the risk for surgical bleeding in association with clopidogrel alone or plus aspirin in stent carriers, and increased bleeding has only been described for associated aspirin doses in excess of 200 mg.

Ticagrelor and prasugrel seemingly have a greater antiplatelet effect as compared even with clopidogrel, hence the bleeding risk related to these new antiplatelets would be higher.

In view of this information -with a low evidence level- clopidogrel and ticagrelor should be discontinued 5 days, and prasugrel 7 days, before any procedure with high bleeding risk (43).

Is antiaggregation, whether single or dual, a contraindication for any endoscopic technique?

No convincing data are available that turn single antiaggregation into an absolute contraindication for any endoscopic technique (7), but ASA -where this algorithm may be used somewhat safely- and novel antiplatelets -which may require a more careful assessment- should probably be considered on an individual basis.

As regards dual antiaggregation no papers discuss its actions, although in view of the current data interventional procedures should likely be avoided during its use. At any rate, the decision should be made based on endoscopic and thrombotic risk: In the presence of low endoscopic risk both drugs may be used; regarding high risk, this will hinge upon thrombotic risk -if low, clopidogrel will be discontinued and the procedure will be performed under aspirin; when high, attempts will be made to delay the endoscopic procedure or a bridge therapy may be considered with glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors.

What is in practice the regimen used to reverse antiaggregation?

In all cases delaying therapy until thrombotic risk is minimal is most desirable; in cases on dual antiaggregation, clopidogrel can be discontinued 7 days before while maintaining aspirin as per the prescribed regimen.

The different guidelines (6) have posited suggestions for managing antiaggregation that are mainly based on defining whether indication is urgent, and assessing extant indications: For primary and secondary indications, considering their low thrombotic risk, aspirin may be withdrawn; aspirin is to be maintained for all other scenarios.

In a consensus paper between the American College of Cardiology and the American College of Gastroenterology time periods are established from the time of coronariography to stent implantation or angioplasty regarding actions to be taken with antiplatelets. The cut-off is set in 14 days to avoid elective procedures or to undertake them with aspirin alone; waiting time should be 30 to 45 days for angioplasty with metallic stents, and 1 year for covered stents (15).

The indication of a bridge therapy with LMWH in antiaggregated patients undergoing endoscopy with an add-on procedure is now much debated. No evidence exists for its benefits (40), and the fact that it will not effectively protect from thrombosis in patients with coronary stents seems clear, although its potential protective role in situations at risk of thrombosis and bleeding with relatively undelayable endoscopies has been suggested because of its antiaggregating role.

Upon antiplatelet drug reintroduction we should reassess both bleeding and thrombosis risks. Initially, they will be reintroduced at 24 hours after the endoscopic procedure, except in situations with high bleeding risk, where a cardiologist or neurologist or hematologist should be included in the assessment.

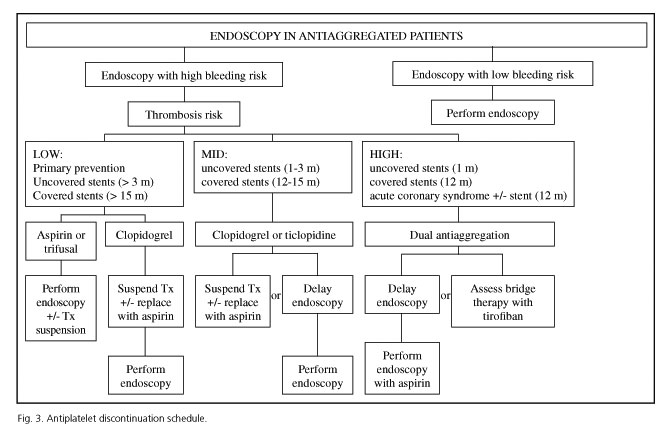

Based on this we developed a working paper to aid clinicians in their decision-making before endoscopy procedures, delineating a procedure's bleeding risk and then defining its thrombotic risk (Fig. 3).

What is the role of a glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitor in the reversal of antiaggregation?

In a prospective, non-controlled study of 30 patients undergoing undelayable major surgery within 6 months following the placement of a coated stent a glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitor, tirofiban i.v. (Fig. 4), was used as bridge therapy, with clopidogrel being discontinued 5 days before, with no resulting coronary or bleeding condition: this represents an interesting possibility for this subgroup of patients (44). However, no other papers have been reported on this topic, hence we must follow on cautiously and consider it an option only in the setting of joint protocols involving cardiology and hematology departments.

Which are the primary anticoagulants available in spain (other than heparins)? (Table VI)

Figure 5 shows where primary anticoagulants act. Most common options, warfarin and acenocoumarol, are well known and possess a longer half-life, which may lead to consider bridge therapies with low molecular weight heparin in settings with bleeding risk.

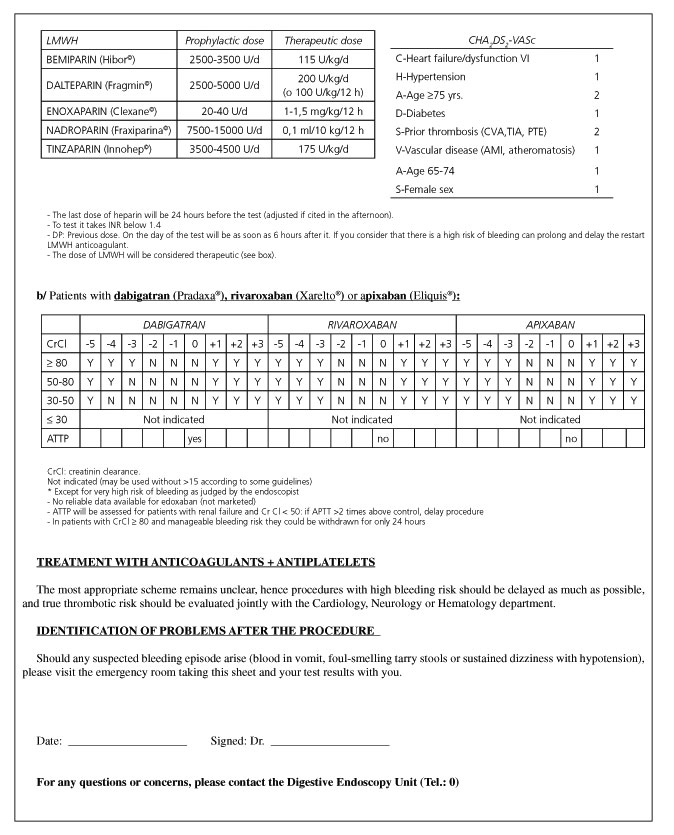

New oral anticoagulant (NOAC) drugs have been marketed of late, including direct thrombin inhibitors (dabigatran) and factor Xa inhibitors (rivaroxaban and apixaban). Edoxaban remains unavailable as of today. These drugs have no specific antidote, therefore it is advisable that sites implement action protocols for the management of bleeding complications, surgery preparation, and invasive procedures in patients receiving NOACs. Their anticoagulant effect lasts for approximately 24 hours, but may be longer in the presence of renal failure (up to 4 days), each one having a different clearance rate. Knowing this is therefore crucial to establish a NOAC discontinuation scheme before an interventional procedure. While they prolong bleeding time, coagulation tests are useless for level monitoring, albeit dabigatran will be considered to no longer have anticoagulant effect when APTT becomes normal (45). Using therapeutic doses the APTT value may be longer than the control by a factor of 2 or 3.

In patients undergoing procedures with low bleeding risk discontinuation could be restricted to just one dose (that is, 10 h for dabigatran and apixaban; 20 h for rivaroxaban) or could even be skipped for gastroscopy or colonoscopy, with or without biopsy taking; in the presence of high risk (Table VII) they should be discontinued for between 2 to 3 times the half-life (45). These drugs are reintroduced after 24 hrs as their fast action provides anticoagulation immediately. However, this may be delayed for 2 days for procedures with high bleeding risk.

Dabigatran and rivaroxaban increase the risk of GI bleeding by 1.5 as compared to warfarin, whereas apixaban is similar to the latter (46).

What indications do anticoagulants have? (Table VIII)

A gastroenterologist should know his trade, even more so when indications for these drugs, which have reduced vascular mortality in patients at risk, are increasingly numerous.

Regarding atrial fibrillation, their indication is established for patients with valve involvement and patients with thrombotic risk according to the CHA2DS2-VASc (47) classification (C- congestive heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction, H- hypertension, A- age ≥ 75, D- diabetes, S- prior stroke or thrombotic accident (CVA, TIA, PTE), V- vascular disease (prior myocardial infarction, peripheral arteriopathy or aortic plaques), A- age between 65 and 74, and S- female sex). Anticoagulation is deemed indicated when a criterion is met in the setting of atrial fibrillation (48) (Table IX). The higher the number of criteria met, the higher the risk for thrombosis should anticoagulation be discontinued (49).

On the other hand, when making decisions for patients with heart disease the HAS-BLED score is also used, which assesses bleeding risk:

- H- Hypertension: 1 point if not controlled, with SBP ≥ 160.

- A- Impaired renal (1 point) or hepatic (1 point) or renal and hepatic (2 points) function.

- S- History of stroke (1 point), especially of the lacunar type.

- B- History of bleeding, anemia, or predisposition to bleeding (1 point).

- L- Labile, unstable or high INR, or INR with less than 60% of time within the therapeutic range (1 point).

- E- Age ≥ 65 years (1 point).

- D- Drugs and/or alcohol: antiplatelet drugs (1 point), drinking 8 or more alcohol-containing beverages per week (1 point), or both (2 points).

A score of 3 or above suggests a higher bleeding risk the year after anticoagulation, hence increased follow-up or dose reductions for anticoagulants such as dabigatran might be indicated.

Is anticoagulation a contraindication for any endoscopic technique?

- Yes, for endoscopic techniques with high bleeding risk.

- No, not for diagnostic procedures, including biopsy taking (7).

- In the emergency setting any technique may be considered after reversing anticoagulation.

There is doubt about the adequate INR value for endoscopic procedures with high bleeding risk. Endoscopic guidelines mention levels above 1.4 on the day of the procedure (laboratory monitoring is mandatory), although some cardiology guidelines advocate for levels below 2.0. Bleeding risk, as already mentioned, continues to increase even when guidelines are properly followed, thus we may assume the 1.4 value as general recommendation, even if higher levels might be endorsed in situations with very high thrombotic risk, such as the use of metallic prostheses.

Which conditions entail a higher thrombotic risk when reversing anticoagulation?

The ASGE (2) defines thrombotic risk as comprising two levels (Table X).

This has been generally endorsed by other authors, in manuals (50), reviews (51), and clinical guidelines (7), even though the CHA2DS2-VASc classification is favoured in cardiology environments, specifically when referring to atrial fibrillation. Distinguishing three levels of thrombotic risk might be practical when considering the various options available to act and to apply bridge therapies (52) (Table XI), and this is what we include in our proposed algorithm. We distinguish between high and very high risk mainly for practical purposes, since only in very high risk settings have the prophylactic benefits of enoxaparin in divided doses, as opposed to other LMWHs, been demonstrated.

Which is the most practical regimen to reverse anticoagulation?

In a decision analysis based on the implementation of the ASGE clinical guidelines (2,4) the following strategies were deemed most cost-effective (53):

- In patients with low thrombotic risk (for instance atrial fibrillation without valve disease) or if polypectomy possibilities exceed 60%, stop warfarin 5 days before.

- In screening colonoscopies, where polyps are expected in over 35% of patients, maintain warfarin at reduced dosage.

- For polypectomy possibilities equal to or lower than 1%, continue with warfarin.

There is a somewhat defined agreement on the right regimen, according to both endoscopy type and anticoagulation indication (9).

Attitude will be defined based on the endoscopic procedure's bleeding risk, and then action will be according to the type of anticoagulant the patient is on: If the patient is taking acenocoumarol or warfarin (the latter must be discontinued for one extra day as compared to acenocoumarol) we must initiate a bridge therapy with LMWH adjusted to thrombotic risk. If on a NOAC, decisions will be made depending on creatinine clearance (CrCl), as the discontinuation scheme varies depending upon the molecule in use (Fig. 6). Whether a bridge therapy with LMWH should be used for patients previously on a NOAC is subject to debate, but should discontinuation be adjusted according to CrCl the patient will not be unprotected or overmedicated.

The reintroduction of an anticoagulant after the procedure will usually take place after 6 hours, except in high-risk situations, where it may be delayed 24 hours should thrombotic risk allow it. Subjects on bridge therapy will be dosed at 24 hours, and LMWH may be extended and anticoagulant reintroduction delayed when bleeding risk is high, always with agreement by a cardiologist, neurologist or hematologist.

What is the role of low molecular weight heparin in the reversal of anticoagulation?

In their guidelines, the ASGE (4) suggests a management scheme using low molecular weight heparin as bridge for high thrombotic risk patients; the problem is that neither doses nor the proper timing for heparin reintroduction have been defined, although this is deemed to oscillate between 2 and 6 hours after the procedure, and consensus is to be sought with the remaining specialists involved. Other authors suggest a reduction of LMWH doses before interventional procedures, with early reintroduction in high-risk patients, even if this is described for diagnostic catheterisms rather than techniques with high bleeding risk in an assay (Table XII).

LMWH has been used in high and double doses (54). However, there is no clear evidence regarding its superiority over low, single doses, but bleeding does seem to increase (7). Many coagulation clinics establish dose titration regimens according to thrombotic risk, and every site should define theirs in agreement with hematologists and cardiologists.

The effectiveness and safety of various LMWH schemes as bridge therapy for the management of anticoagulation withdrawal has been demonstrated in non-randomized studies with enoxaparin sodium (55), dalteparin (56) or bemiparin (57), the latter providing the potential benefit of single doses. A Spanish paper assesses its protective effect for gastroscopy and colonoscopy using a user-friendly protocol consisting of single doses of 3,500 units of bemiparin (57). However, this was about gastroscopy and colonoscopy with low bleeding risk, and a dose of 3,500 units might be inadequate in high thrombotic risk settings.

However, bridge therapy poses some concern regarding effect enhancement when giving two anticoagulants concomitantly, which may increase bleeding risk. Furthermore, renal LMWH clearance may be problematic because of overdosing in subjects with uncontrolled or unknown renal failure.

What should be done in cases with concomitant antiaggregation and anticoagulation?

Such regimen would only be indicated for a condition demanding oral anticoagulation (atrial fibrillation, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or valvular prosthesis) and coronary disease (acute coronary syndrome and/or stent implantation) (58). At any rate, it is advisable that this scheme be maintained for the shortest time possible. No recommendations are available in the existing guidelines and papers in endoscopic procedures. Recommendations do exist in some consensus European guidelines in the field of cardiology, where it is stated that in the presence of severe acute bleeding and triple therapy the monitoring of INR levels below 2 may be necessary while maintaining clopidogrel and low-dose aspirin. This is an increasingly common situation, and cases should be managed on an individual basis.

What should be done for patients on aspirin, antiplatelets or anticoagulants outside accepted indications?

In such situations therapy discontinuation before the endoscopic procedure would be most appropriate, as increasing the risk of bleeding, however small, while maintaining the thrombotic risk would be senseless.

May we recommend a practical scheme for antiaggregated and/or anticoagulated patients?

Mixed management together with cardiologists, hematologists, and neurologists is important, considering patient conditions on an individual basis.

While a practical proposal is made at the end of the protocol (Annex 1), we must combine the risk estimates and feelings the endoscopist may have after the procedure with those of a cardiologist, hematologist or neurologist in order to agree on the timing for discontinuation (rather stable) and reintroduction (more flexible).

Guidelines are helpful in the decision-making underlying medical acts, rather than tight schemes to be followed stringently, as evidence for the latter is presently weak.

Is screening colonoscopy a technique requiring a different behaviour as compared to standard diagnostic colonoscopy?

In the various series of screening colonoscopies in our setting, the possibility of significant polypectomy -for polyps larger than 10 mm- is encountered in 50% to 60% of patients.

As seen above, a reduction of anticoagulant doses is considered to be cost-effective (50), albeit this is uncommon in our setting. In these patients a bridge therapy with LMWH is perhaps most appropriate from a practical standpoint.

As regards antiplatelets, aspirin will not be withdrawn, regardless of dosage. If on clopidogrel, we shall inform the patient that the bleeding risk is slightly increased, or we may change it for aspirin, and about the possibility of delaying the procedure until it may be withdrawn.

If on dual antiaggregation, consider clopidogrel discontinuation if possible (as per established schemes) and maintain aspirin.

With a consensual attitude in our team, we chose to manage screening as a high-risk endoscopy given the high rate of polypectomies (> 50%), in order to prevent second procedures from happening, although patients should be involved in the decision-making.

How important is patient perspective when the decision is made to discontinue an anticoagulant or antiplatelets drug?

This point was discussed given the relevance of discontinuation for patient health, and patients prefer the risk of side effects (including bleeding) to the risk of potential cardiovascular events (59). This appreciation should prompt us to make decisions on an individual basis prior to the procedure, with time enough for the patient to make up his or her mind.

The finding of polyps during colonoscopy is increasingly common in patients on anticoagulants and/or antiplatelet drugs. In such case decisions should be agreed upon before the procedure, particularly for sedated patients. The informed consent should approach potential polypectomy, and describe its benefits and risks, as well as the need to repeat both the procedure and the preparation should polypectomy be decided against.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the board members of SEED, SEPD, GTCV-SEC, and SETH for their contributions and corrections in order to improve and make sense of this document.

We particularly acknowledge Dra. Inmaculada Roldán (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital La Paz, Madrid) and Dr. Enric Brullet (Servicio de Digestivo, Hospital Parc Taulí, Sabadell) for their specific contributions.

References

1. Ezekowitz MD. Anticoagulation interruptus: Not without risk. Circulation 2004;110:1518-9. [ Links ]

2. Eisen, GM, Baron, TH, Dominitz, JA, et al. Guideline on the management of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;55:775. [ Links ]

3. Baker RI, Coaughlin PB, Gallus AS, et al.; the Warfarin Reversal Consensos Group. Warfarin reversal: Consensus guidelines, on behalf of the Australasian Society of Trombosis and Haemostasis. Medical Journal of Australia 2004;181:492-7. [ Links ]

4. Zuckerman, MJ, Hirota, WK, Adler, DG, et al. ASGE guideline: The management of low-molecular-weight heparin and nonaspirin antiplatelet agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61:189-94. [ Links ]

5. Boustière C, Veitch A, Vanbiervliet G, et al. ESGE Guideline: Endoscopy and antiplatelet agents. Endoscopy 2011;43:445-58. [ Links ]

6. Alberca de las Parras F. Guía de práctica clínica para el manejo de la coagulación en pacientes sometidos a técnicas endoscópicas. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2010;102:124-38. [ Links ]

7. Veitch AM, Baglin TP, Gershlick AH, et al. Guidelines for the management of anticoagulant endoscopic procedures and antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures. Gut 2008;57:1322-9. [ Links ]

8. Becker RC, Scheiman J, Dauerman HL, et al; American College of Cardiology and the American College of Gastroenterology. Management of platelet-directed pharmacotherapy in patients with atherosclerotic coronary artery disease undergoing elective endoscopic gastrointestinal procedures. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:2903-17. [ Links ]

9. Gerson LB, Gage BF, Owens DK, et al. Effect and outcomes of the ASGE guidelines on the periendoscopic management of patients who take anticoagulants. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:1717-24. [ Links ]

10. Fujishiro M, Oda I, Yamamoto Y, et al. Multi-center survey regarding the management of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy for endoscopic procedures in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;24:214-8. [ Links ]

11. Radaelli F, Paggi S, Terruzzi V, et al. Management of warfarin-associated coagulopathy in patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding: A cross-sectional physician survey of current practice. Dig Liver Dis 2011;43:444-7. [ Links ]

12. Ono S, Fujishiro M, Hirano K, et al. Retrospective analysis on the management of anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents for scheduled endoscopy. J Gastroenterol 2009;44:1185-9. [ Links ]

13. Lobo B, Saperas E. Tratamiento de la hemorragia digestiva por ruptura de varices esofágicas. http://www.prous.com/digest/protocolos/view_protocolo.asp?id_protocolo=18. 2004 Prous Ed. [ Links ]

14. Cukor B, Cryer BL. The risk of rebleeding after an index GI bleed in patients on anticoagulation (abstract DDW 2008). Gastrointest Endosc 2008;67:AB24. [ Links ]

15. Heidbuchel H, Verhamme P, Alings M, et al. European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of new oral anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Eurospace 2013;15: 625-51. [ Links ]

16. Parra-Blanco A, Kaminaga N, Kojima Y, et al. Hemoclipping for postpolypectomy and postbiopsy colonia bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc 2000;51:37-41. [ Links ]

17. Smith LE. Fiberoptic colonoscopy: Complications of colonoscopy and polyupectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 1976;19:407-12. [ Links ]

18. Sieg A, Hachmoeller-Eisenbach U, Eisenbach T. Prospective evaluation of complications in outpatient GI endoscopy: A survey among German gastroenterologists. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;53:620-7. [ Links ]

19. Di Giorgio P, De Luca L, Calcagno G, et al. Detachable snare versus epinephrine injection in the prevention of postpolypectomy bleeding: A randomized and controlled study. Endoscopy 2004;36:860-3. [ Links ]

20. Bason MD, Manzini L, Palmer RH. Effect of nabumetone and aspirin on colonic mucosal bleeding time. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:539-42. [ Links ]

21. Nakajima H, Takami H, Yamagata K, et al. Aspirin effects on colonia mucosal bleeding: implications for colonia biopsy and polypectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 1997;40:1484-8. [ Links ]

22. Hui AJ, Wong RM, China JK, et al. Risk of colonoscopic polipectomy bleeding with anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents: analisis of 1657 cases. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2004. [ Links ]

23. Shiffman ML, Farrel MT, Yee YS. Risk of bleeding alter endoscopic biopsy or polypectomy in patients taking aspirin or other NSAIDs. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 1994;40:458-62. [ Links ]

24. Yousfi M, Gostout CJ, Baron TH, et al. Postpolypectomy lower gastrointestinal bleeding: Potencial role of aspirin. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:1785-9. [ Links ]

25. Kimchi NA, Broide E, Scapa E, et al. Antiplatelet therapy and the risk of bleeding induced by gastrointestinal endoscopio procedures. A systematic review of the literature and recommendations. Digestion 2007;75:36-45. [ Links ]

26. Witt DM, Delate T, McCool KH, et al.; WARPED Consortium. Incidence and predictors of bleeding or thrombosis after polypectomy in patients receivin g and not receiving anticoagulation therapy. J Thromb Haemost 2009;7:1982-9. [ Links ]

27. Gerson LB, Michaels L, Ullah N, et al. Adverse events associated with anticoagulation therapy in the periendoscopic period. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:1211-7. [ Links ]

28. Friedland S, Sedehi D, Soetikno R. Colonoscopic polypectomy in anticoagulated patients. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:1973-6. [ Links ]

29. Hirouchi A, Nakayama Y, Kajjyama M, et al. Removal of small colorectal polyps in anticoagulated patients: a prospective randomized comparison of cold snare and conventional polypectomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2013;79:417-2. [ Links ]

30. Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: An attemp at consensus. Gastorintest Endosc 1991;37:383-93. [ Links ]

31. Hui CK, Lai KC, Yuen MF, et al. Does withholding aspirrin for one week reduce the risk of post-sphinsterotomy bleeding? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:929-36. [ Links ]

32. Nelson DB, Freeman ML. Mayor haemorrhage from endoscopio sphincterotomy: risk factor analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol 1994;19: 283-7. [ Links ]

33. Weinberg BM, Shindy W, Lo S. Dilatación esfinteriana endoscópica con balón (esfinteroplastia) versus esfinterotomía para los cálculos del conducto biliar común (Revisión Cochrane traducida). En: La Biblioteca Cochrane Plus, 2007 Número 4. Oxford: Update Software Ltd. Disponible en: http://www.update-software.com. (Traducida de The Cochrane Library, 2007 Issue 4. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [ Links ]).

34. Mönkemüller K, Fry LC, Neumann H, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic utility of double balloon endoscopy: experience with 225 procedures. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2007;37:216-23. [ Links ]

35. Koh R, Hirasawa K, Yahara S, et al. Antithrombotic drugs are risk factors for delayed postoperative bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasms. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2013;78:476-83. [ Links ]

36. Singh D, Laya AS, Vaidya OU, et al. Risk of bleeding after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). Dig Dis Sci 2012;57:973-80. [ Links ]

37. Camm AJ, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal 2011;32:2999-3054. [ Links ]

38. Steg G, James SK, Atar D, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. The Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) European Heart Journal 2012;33:2569-619. [ Links ]

39. Fuentes B, Gállego J, Gil-Nunez A, et al.; por el Comité ad hoc del Grupo de Estudio de Enfermedades Cerebrovasculares de la SEN. Guía para el tratamiento preventivo del ictus isquémico y AIT (II). Recomendaciones según subtipo etiológico. Neurología 2014;29:168-83. [ Links ]

40. Grines CL, Bonow RO, Casey DE Jr., et al. Prevention of premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery stents: A science advisory from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, American College of Surgeons, and American Dental Association, with representation from the American College of Physicians. Circulation 2007;115:813-8. [ Links ]

41. Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. Guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50;159-241. [ Links ]

42. Cohen Arazi H, Carnevalini M, Falconi E, et al. The association of antiplatelet aggregation effect of aspirin and platelet count. Possible dosage implications. Revista Argentina de Cardiología 2012;80. [ Links ]

43. Fox KA, Mehta SR, Peters R, et al.; Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent ischemic Events Trial. Benefits and risks of the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin in patients undergoing surgical revascularization for non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: the clopidogrel in unestable angina to prevent recurrent ischemic events (CURE) trial. Circulation 2004;110:1202. [ Links ]

44. Savonitto S, Urbano MD, Caracciolo M, et al. Urgent surgery in patients with a recently implanted coronary drug-eluting stent: a phase II study of "bridging" antiplatelet therapy with tirofiban during temporary withdrawal of clopidogrel. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2010;104:285-91. [ Links ]

45. Desai J, Granger CB, Weitz JI, et al. Novel oral anticoagulants in gastroenterology practice. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2013;78:227-39. [ Links ]

46. Desai J, Kolb JM, Weitz JI, et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding with the oral anticoagulants- defining the issues and the management strategies. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2013;110:205-12. [ Links ]

47. Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, et al. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: The Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Chest 2010;137:263-72. [ Links ]

48. Camm AJ, Lip GYH, De Caterina R, et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. An update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. European Heart Journal 2012;33:2719-47. [ Links ]

49. Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, et al. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: Results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 2001;285:2864-70. [ Links ]

50. Morillas JD, Simón MA. Endoscopia: preparación, prevención y tratamiento de las complicaciones. En: Tratamiento de las enfermedades gastroenterológicas. Asociación Española de Gastroenterología. Ed SCM; 2006. [ Links ]

51. Kamath PS. Gastroenterologic procedures in patients with disorders of hemostasis. Up To Date. http://www.uptodate.com/physicians/gasthepa_toclist.asp 2007. [ Links ]

52. You JJ, Singer DE, Howard PA, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis. 9th ed. American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141(2 Supl.):e531S-e575S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2304. [ Links ]

53. Gerson LB, Triadafilopoulos G, Gage BF. The management of anticoagulants in the periendoscopic period for patients with atrial fibrillation: a decision analysis. Am J Med 2004;116: 451-9. [ Links ]

54. Seshadri N, Goldhaber SZ, Elkayam U, et al. The clinical challenge of brinding anticoagulation with low-molecular-weigth heparin in patients with mecanical prosthetic heart valves: an evidence-based comparative review focusing on anticoagulation options in pregnant and nonpregnant patients. Am Heart J 2005;150:27-34. [ Links ]

55. Douketis JD, Johnson JA, Turpie AG. Low-molecular-weith heparin as bringing interruption of warfarin. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1319-26. [ Links ]

56. Turpie AGG, Johnson J. Temporary discontinuation of oral anticoagulants: Role of low molecular weight heparin (dalteparin). Circuation 200;102:II-826. [ Links ]

57. Constans M, Santamaria A, Mateo J, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin as bridging therapy during interruption of oral anticoagulation in patients undergoing colonoscopy or gastroscopy. Int Clin J Prac 2007;61:212-7. [ Links ]

58. Wijns W, Kolh P, Danchin N, et al. Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) European Heart Journal 2010;31:2501-55. [ Links ]

59. Devereaux PJ, Anderson DR, Gardner MJ, et al. Differences between perspectives of physicians and patients on anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation: observational study. BMJ 2001;323:1218-22. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Fernando Alberca de las Parras.

Unit of Digestive Diseases.

Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca.

Ctra. Madrid-Cartagena, s/n.

30120 El Palmar.

Murcia, Spain

e-mail:

alberca.fernando@gmail.com

Received: 25-01-2015

Accepted: 16-02-2015

texto en

texto en