Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.107 no.10 Madrid oct. 2015

Efficacy and safety of simeprevir in combination with peginterferon and ribavirin for patients with hepatitis C genotype 1 infection: A meta-analysis of randomized trials

Xianghua Cui1,2, Yuanyuan Kong3 and Jidong Jia1,2

1 Liver Research Center. Beijing Friendship Hospital. Capital Medical University. Beijing, China.

2 Beijing Key Laboratory of Translational Medicine in Liver Cirrhosis. Beijing, China.

3 Clinical Epidemiology and EBM Unit. Beijing Friendship Hospital. Capital Medical University. Beijing, China

ABSTRACT

Background and aim: A simeprevir (SMV)-based regimen has shown promising results in treating chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. This meta-analysis aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of simeprevir for treating HCV genotype 1 infection.

Methods: MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched, along with the reference lists of retrieved articles. The meta-analysis only included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared the efficacy and safety of addition of SMV to peginterferon (PegIFN) and ribavirin (RBV) (triple regimen) with PegIFN/RBV alone (dual regimen) in treating chronic HCV genotype 1 infection.

Results: A total of seven RCTs involving 2,301 patients were included. The triple regimen had a higher pooled sustained virologic response (SVR) rate [odds ratio (OR) = 4.57; 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.34-6.27; p < 0.001)] and lower pooled relapse rate [relative risk (RR) = 0.41; 95% CI: 0.33-0.50; p < 0.001] than the dual regimen had. The pooled incidence of adverse events (AEs) was comparable between the two regimens (RR = 1.01; 95% CI: 0.99-1.03; p = 0.339), whereas the incidence of serious AEs in the triple regimen was lower (RR = 0.7; 95% CI: 0.50-0.98; p < 0.05).

Conclusions: The meta-analysis demonstrates that the addition of SMV to pegIFN and RBV is effective and well-tolerated in treating chronic HCV genotype 1 infection, with a low incidence of AEs.

Key words: Simeprevir. Chronic hepatitis C. Meta-analysis.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection still carries a major global health burden. It is estimated that ~160 million individuals, i.e. 2.35% of the world population, are chronically infected with HCV and ~350,000 people die from HCV-related cirrhosis and liver cancer each year (1-4).

The past two decades have witnessed progressive improvements in the sustained virologic response (SVR) rate, initially with peginterferon and ribavirin (PegIFN/RBV), and the later addition of telaprevir or boceprevir (3-8). However, all these combination or triple therapies often cause frequent and severe adverse events (AEs) and increase the complexity of these treatments (9-11). Recently, several all-oral combination trials (12-16) with different direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) have shown high SVR rates, excellent tolerability, and shortened treatment duration in the US, EU and other developed countries, but PegIFN-based treatment is still widely used in most developing countries (17).

Simeprevir (SMV, TMC435) is an oral NS3/4A HCV protease inhibitor with activity against all HCV genotypes except genotype 3 (18,19). It has been approved in several countries as a triple regimen (SMV/PegIFN/RBV) for chronic HCV infection (19,20). Recently, a pooled safety analysis of five phase IIb and III randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (21) demonstrated that the addition of SMV to PegIFN/RBV is well tolerated in patients infected with HCV genotype 1. However, the efficacy of SMV was not addressed in the analysis.

Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis of all available RCTs to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the efficacy and safety of addition of SMV to the PegIFN/RBV regimen in patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (22).

Methods

Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials to identify and select relevant studies published up to February 2015. We also scanned the reference lists of relevant reviews and articles, and checked the clinical trial registry for additional studies (clinicaltrials.gov). The following search terms were used: "hepatitis C virus", "hepatitis C", "HCV", "simeprevir", "SMV", "TMC435". No language or publication restrictions were imposed.

Study selection

The following criteria were applied for study inclusion: a) RCTs; b) male or female patients, who had chronic infection with HCV genotype 1; c) SMV administered at any dose and duration; and d) studies that compared SMV plus PegIFN/RBV (triple regimen) with placebo plus PegIFN/RBV (dual regimen).

Exclusion criteria were: a) non-randomized trials; b) non-human studies; c) studies including patients co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus or hepatitis B virus; d) studies with patients who had undergone liver transplantation; and e) duplicate data or publications.

Data extraction

The following information was extracted from each study according to the aforementioned inclusion criteria: a) general characteristics, including first author, published year, geographical area, sample size, median age, gender, dosage and duration of SMV; b) primary outcomes of each RCTs, including the rate of SVR (defined as an undetectable HCV RNA level 12 or 24 weeks post-cessation of treatment) and viral relapse (defined as a detectable HCV RNA level during follow-up or at the time of SVR assessments after achieving undetectable levels at the end of the treatment). Secondary outcomes, including the rate of rapid virologic response (RVR), the incidence of AEs and serious AEs. RVR was defined as undetectable HCV-RNA 4 weeks after treatment initiation. AEs in these included RCTs were defined as occurring in > 25% of the treated patients during the first 12 weeks of treatment and during the entire treatment period. Serious adverse events were referred to AEs which may lead to permanent discontinuation of at least one study drug.

Quality assessment

Two independent assessors (Cui X.H. & Kong Y.Y.) appraised the quality of every trial using a 5-point quality scale, i.e. the Jadad system (23), which including randomization (0-2 points), double blinding (0-2 points) and the description of withdrawals and dropouts (0 or 1 point). Final scores of 0-2 were deemed as low quality, whereas scores of > 3 were considered as high quality. Any discrepancies between the two assessors were resolved by discussion with a third assessor (Jia J.D.).

Statistical analysis

Dichotomous outcomes were pooled and presented as odds ratio (OR) or relative risk (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneity among the included trials was measured using the Cochran Q test to test for heterogeneity and the I2 statistic test to quantify the between-study heterogeneity. PQ statistic < 0.1 was deemed statistically significant and I2 > 50% indicated substantial heterogeneity. With respect to heterogeneous data, a random-effects model was used (24); otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used (25). Finally, potential publication bias was investigated using Begg's funnel plot and Egger's regression test (26,27).The meta-analysis was conducted using the Stata/SE software (STATA), version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). All p values were two-sided and < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Study characteristics

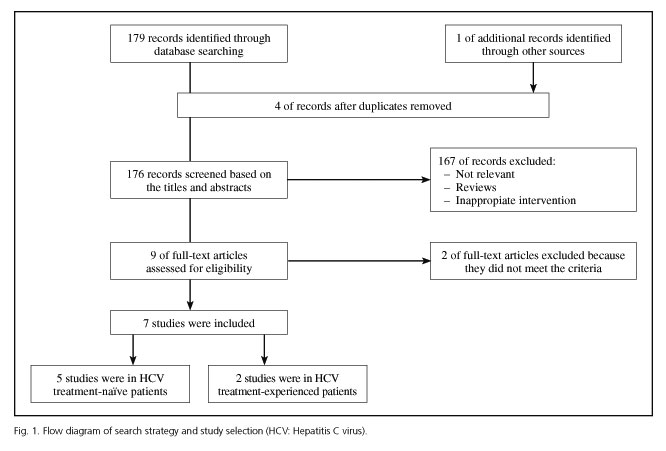

The database search identified 180 relevant titles and abstracts that potentially could have been included in this meta-analysis. One hundred and sixty-seven studies were excluded after briefly reading the titles and abstracts, and two were excluded after reading the full texts. Ultimately, seven RCTs (28-34) with a total of 2,301 patients were included in our analysis: five enrolled treatment-naïve patients (29-33) and two treatment-experienced patients (28,34) (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics of the included trials are briefly described in table I. A total of 1,688 patients in the analysis were randomized to the triple regimen and 613 to the dual regimen. The included trials were mainly conducted in North America, Europe and Asia-Pacific regions.

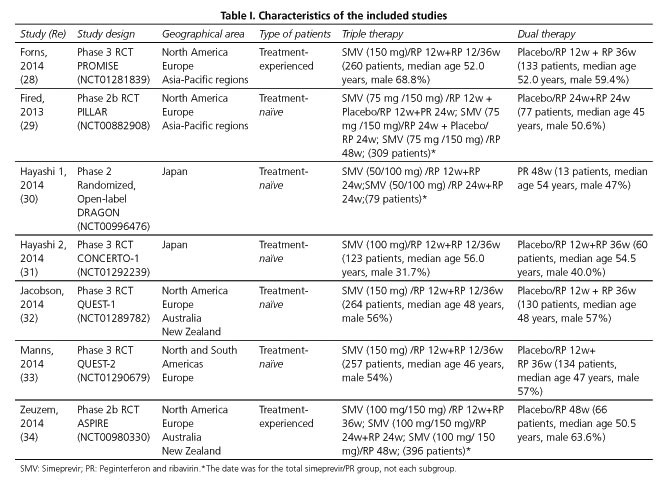

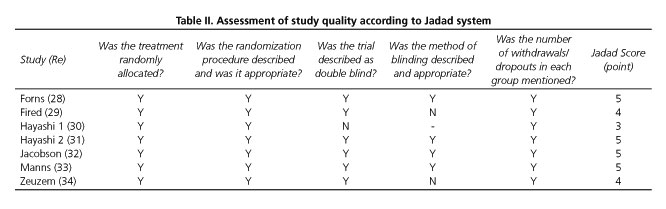

Quality assessment of the studies

The results of the quality assessment of the included studies according to the Jadad system are shown in table II. All the seven included RCTs described briefly the randomization procedure that they had applied. Six of the RCTs used double-blind methods and four of them described the methods appropriately. All the trials stated the number and reasons for patient withdrawal. All seven RCTs (28-34) were regarded as having good methodological quality and their score ranged from 3 to 5 points.

Quantitative data synthesis

Primary outcome

SVR

There was between-study heterogeneity among the seven RCTs (I2 = 51.0%, PHeterogeneity = 0.057). Thus, the results were pooled using the random-effects model, which indicated that the SVR rate in the triple regimen (1,323/1,688; 78.4%) was significantly higher than that in the dual regimen (289/613; 47.1%), with a pooled OR of 4.57 (95% CI = 3.34-6.27; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Subgroup analysis according to patients' HCV genotype (1a and 1b), IL28B genotype (CC, CT and TT), METAVIR fibrosis score (F0-2 and F3-4), treatment background (treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced) and administered dosage of SMV (100 or 150 mg) were in accordance with the above results (Table III).

The SVR rates in the HCV genotype 1a subgroup (OR = 3.72; 95% CI = 2.23-6.19) and 1b subgroup (OR = 6.05; 95% CI = 4.44-8.25) were significantly higher than that of the dual regimen. As regards the IL28B genotype, triple regimen more frequently than dual regimen achieved SVR among in 405 patients with IL28B genotype CC (OR = 5.37; 95% CI = 3.02-9.54), in 831 patients with IL28B genotype CT (OR = 5.93; 95% CI = 4.28-8.21) and in 194 patients with IL28B genotype TT (OR = 5.02; 95% CI = 2.52-10.01). Moreover, SVR was more frequently observed in triple regimen than dual regimen in patients with METAVIR fibrosis score F0-2 (OR = 4.33; 95% CI = 3.32-5.64) and F3-4 (OR = 5.49; 95% CI = 2.66-11.31).The SVR rates in the treatment-naïve patients (OR = 3.71; 95% CI = 2.88-4.79) and treatment-experienced patients (OR = 7.09; 95% CI = 4.89-10.26) were significantly higher than for the dual regimen. Similar results were also found in patients receiving SMV at 100 mg QD (OR = 5.41; 95% CI = 2.78-10.54) and 150 mg QD for 12 weeks (OR = 4.66; 95% CI = 3.43-6.33) (Table III).

From the results of the subgroup analysis, we concluded that the above-mentioned different stratification factors may have contributed to the heterogeneity in SVR rate.

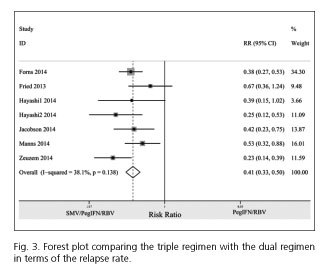

Relapse rate

The relapse rate for the triple regimen was less frequent than for the dual regimen (RR = 0.41; 95% CI= 0.33-0.50). No between-study heterogeneity was observed among the included studies (I2 = 38.1%; PHeterogeneity = 0.138) (Fig. 3).

Secondary outcome

RVR

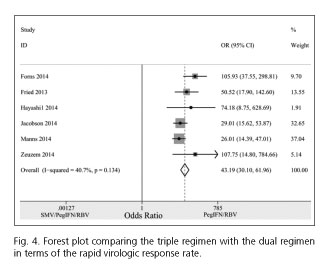

Pooling the six trials (28-30,32-34) that had provided RVR rates, the results showed that the RVR rate in the triple regimen (1,146/1,552; 73.8%) was dramatically higher compared with the dual regimen (42/545; 7.7%), with a pooled OR of 43.19 (95% CI = 30.10-61.96; p < 0.001) (Fig. 4).

AEs and serious AEs (SAEs)

Four studies (26,27,30,31) in the meta-analysis stated the numbers of patients with AEs, and the pooled incidence of AEs was comparable in the triple and dual regimens (RR = 1.01; 95% CI = 0.99-1.03). There was no significant between-study heterogeneity in these two regimens (I2 = 30.5%, PHeterogeneity = 0.229) (Fig. 5).

The incidence of SAEs for the triple regimen was significantly lower than for the dual regimen (RR= 0.70; 95% CI = 0.50-0.98). There was no significant between-study heterogeneity in these two groups (I2 = 0.0%, PHeterogeneity = 0.603) (Fig. 5).

Publication bias

Begg's funnel plot and Egger's test were performed to assess the potential publication bias in the available literature. The shape of the funnel plots appeared symmetrical. Egger's test also showed no statistical significance for the evaluation of publication bias (p = 0.368).

Discussion

This meta-analysis showed that the SVR and RVR rates in the triple regimen with SMV/PegIFN/RBV were significantly higher than those in the dual regimen with PegIFN/RBV, both in treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients. The relapse rate in patients treated with the triple regimen was lower than the rate in those treated with the dual regimen. The pooled incidence of AEs was similar in the two regimens, and the incidence of SAEs in the triple regimen was lower than that in the dual regimen.

We found that the pooled analysis of the SVR rate (I2 = 51.0%) had between-study heterogeneity, which was mainly due to different stratification factors. However, the results of different subgroup were in accordance with those of the overall population regardless of patients' HCV subtype, IL-28B genotype, the severity of liver fibrosis, treatment background and simeprevir dosage. Therefore, we believe that the addition of SMV to PegIFN/RBV may significantly improve the SVR.

AEs in these included RCTs were clinically manageable and the most common AEs caused by the triple regimen were headache, fatigue, and influenza-like illness; all of which were well-known AEs associated with the dual regimen (28-34,35). Our meta-analysis showed that the pooled incidence of AEs with triple therapy was similar to that with the dual regimen, suggesting that addition of SMV to PegIFN/RBV at least did not exacerbate the AEs of the dual regimen. However, only four trials (28,29,32,33) in our meta-analysis provided the numbers of patients with AEs, and larger clinical studies are still needed to validate the long-term safety and tolerability of the triple regimen in patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection.

Surprisingly, the incidence of SAEs with the triple regimen was even lower than that with the dual regimen. By carefully checking the included trials, we found that treatment duration for the triple regimen, which was response-guided (treatment was stopped at week 24 in patients with HCV RNA < 25 IU/mL undetectable or detectable at week 4 and < 25 IU/mL undetectable at week 12; if not, it was continued until week 48, as for patients with the dual regimen) compared with the dual regimen, implying a shorter mean exposure to the dual regimen. This may explain the reduced frequency of SAEs seen with the triple regimen.

There were some limitations in our meta-analysis. First, only seven RCTs were included. Second, there was between-study heterogeneity in SVR rate among the included trials. Finally, most patients in the included trials were white, and nearly all of the patients did not have cirrhosis, therefore our conclusion may have been biased.

In conclusion, SMV in combination with PegIFN/RBV was effective and well-tolerated in the treatment of chronic HCV genotype 1-infected patients. The triple regimen substantially improved the SVR rate and reduced the relapse rate, without worsening the known AEs compared with the dual regimen. However, further studies are needed to investigate the efficacy and safety of SMV in both PegIFN and PegIFN-free combinations, including all oral regimens.

References

1. Lavanchy D. Evolving epidemiology of hepatitis C virus. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011;17:107-15. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03432.x. [ Links ]

2. Cornberg M, Razavi HA, Alberti A, et al. A systematic review of hepatitis C virus epidemiology in Europe, Canada and Israel. Liver Int 2011;31(Supl. 2):30-60. DOI: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02539.x. [ Links ]

3. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol 2014;60:392-420. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.003. [ Links ]

4. Wei L, Lok AS. Impact of new hepatitis C treatments in different regions of the world. Gastroenterology 2014;146:1145-50.e1-4. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.008. [ Links ]

5. Dore GJ. The changing therapeutic landscape for hepatitis C. Med J Aust 2012;196:629-32. DOI: 10.5694/mja11.11531. [ Links ]

6. Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2405-16. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012912. [ Links ]

7. Sherman KE, Flamm SL, Afdhal NH, et al. Response-guided telaprevir combination treatment for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1014-24. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014463. [ Links ]

8. Poordad F, McCone J Jr, Bacon BR, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1195-206. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010494. [ Links ]

9. Gao X, Stephens JM, Carter JA, et al. Impact of adverse events on costs and quality of life in protease inhibitor-based combination therapy for hepatitis C. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2012;12:335-43. DOI: 10.1586/erp.12.10. [ Links ]

10. Hezode C. Boceprevir and telaprevir for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: Safety management in clinical practice. Liver Int 2012;32(Supl. 1):32-8. DOI: 10.1016/S0168-8278(12)60022-1. [ Links ]

11. Qin H, Li H, Zhou X, et al. Safety of telaprevir for chronic hepatitis C virus infection: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Drug Investig 2012;32:665-72. DOI: 10.1007/BF03261920. [ Links ]

12. Suzuki Y, Ikeda K, Suzuki F, et al. Dual oral therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir for patients with HCV genotype 1b infection and limited treatment options. J Hepatol 2013;58:655-62. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.09.037. [ Links ]

13. Hassanein T, Sims KD, Bennett M, et al. A randomized trial of daclatasvir in combination with asunaprevir and beclabuvir in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection. J Hepatol 2015;62:1204-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.025. [ Links ]

14. Everson GT, Sims KD, Rodriguez-Torres M, et al. Efficacy of an interferon-and ribavirin-free regimen of daclatasvir, asunaprevir, and BMS-791325 in treatment-naive patients with HCV genotype 1 infection. Gastroenterology 2014;146:420-9. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.057. [ Links ]

15. Manns M, Pol S, Jacobson IM, et al. All-oral daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for hepatitis C virus genotype 1b: A multinational, phase 3, multicohort study. Lancet 2014;384:1597-605. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61059-X. [ Links ]

16. Kumada H, Suzuki Y, Ikeda K, et al. Daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for chronic HCV genotype 1b infection. Hepatology 2014;59:2083-91. DOI: 10.1002/hep.27113. [ Links ]

17. Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Dore GJ. Epidemiology and natural history of HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;10:553-62. DOI: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.107. [ Links ]

18. Reesink HW, Fanning GC, Farha KA, et al. Rapid HCV-RNA decline with once daily TMC435: A phase I study in healthy volunteers and hepatitis C patients. Gastroenterology 2010;138:913-21. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.10.033. [ Links ]

19. Moreno C, Berg T, Tanwandee T, et al. Antiviral activity of TMC435 monotherapy in patients infected with HCV genotypes 2-6: TMC435-C202, a phase IIa, open-label study. J Hepatol 2012;56:1247-53. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.033. [ Links ]

20. Manns M, Reesink H, Berg T, et al. Rapid viral response of once-daily TMC435 plus pegylated interferon/ribavirin in hepatitis C genotype-1 patients: A randomized trial. Antivir Ther 2011;16:1021-33. DOI: 10.3851/IMP1894. [ Links ]

21. Manns MP, Fried MW, Zeuzem S, et al. Simeprevir with peginterferon/ribavirin for treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection: Pooled safety analysis from Phase IIb and III studies. J Viral Hepat 2015;22:366-75. DOI: 10.1111/jvh.12346. [ Links ]

22. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:W65-94. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [ Links ]

23. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [ Links ]

24. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7: 177-88. DOI: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [ Links ]

25. Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst 1959;22:719-48. [ Links ]

26. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088-101. DOI: 10.2307/2533446. [ Links ]

27. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629-34. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [ Links ]

28. Forns X, Lawitz E, Zeuzem S, et al. Simeprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin leads to high rates of SVR in patients with HCV genotype 1 who relapsed after previous therapy: A phase 3 trial. Gastroenterology 2014;146:1669-79.e3. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.051. [ Links ]

29. Fried MW, Buti M, Dore GJ, et al. Once-daily simeprevir (TMC435) with pegylated interferon and ribavirin in treatment-naive genotype 1 hepatitis C: The randomized PILLAR study. Hepatology 2013;58:1918-29. DOI: 10.1002/hep.26641. [ Links ]

30. Hayashi N, Seto C, Kato M, et al. Once-daily simeprevir (TMC435) with peginterferon/ribavirin for treatment-naïve hepatitis C genotype 1-infected patients in Japan: The DRAGON study. J Gastroenterol 2014;49:138-47. DOI: 10.1007/s00535-013-0875-1. [ Links ]

31. Hayashi N, Izumi N, Kumada H, et al. Simeprevir with peginterferon/ribavirin for treatment-naive hepatitis C genotype 1 patients in Japan: CONCERTO-1, a phase III trial. J Hepatol 2014;61:219-27. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.04.004. [ Links ]

32. Jacobson IM, Dore GJ, Foster GR, et al. Simeprevir with pegylated interferon alfa 2a plus ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection (QUEST-1): A phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2014;384:403-13. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60494-3. [ Links ]

33. Manns M, Marcellin P, Poordad F, et al. Simeprevir with pegylated interferon alfa 2a or 2b plus ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection (QUEST-2): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2014;384:414-26. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60538-9. [ Links ]

34. Zeuzem S, Berg T, Gane E, et al. Simeprevir increases rate of sustained virologic response among treatment-experienced patients with HCV genotype-1 infection: A phase IIb trial. Gastroenterology 2014;146:430-41.e6. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.058. [ Links ]

35. Sherman M, Yoshida EM, Deschenes M, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C patients who failed previous interferon therapy. Gut 2006;55:1631-8. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2005.08311. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Jidong Jia.

Liver Research Center.

Beijing Friendship Hospital.

Capital Medical University.

Beijing, China

e-mail: jia_jd@ccmu.edu.cn

Received: 09-05-2015

Accepted: 01-07-2015