Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versão impressa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.108 no.2 Madrid Fev. 2016

ORIGINAL PAPERS

Irritable bowel syndrome subtypes: Clinical and psychological features, body mass index and comorbidities

Cristiane Kibune-Nagasako, Ciro García-Montes, Sônia Letícia Silva-Lorena and Maria Aparecida-Mesquita

Gastroenterology Unit. Faculty of Medical Sciences. State University of Campinas-Unicamp. Campinas, São Paulo. Brazil

ABSTRACT

Background: Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is classified into subtypes according to bowel habit.

Objective: To investigate whether there are differences in clinical features, comorbidities, anxiety, depression and body mass index (BMI) among IBS subtypes.

Methods: The study group included 113 consecutive patients (mean age: 48 ± 11 years; females: 94) with the diagnosis of IBS. All of them answered a structured questionnaire for demographic and clinical data and underwent upper endoscopy. Anxiety and depression were assessed by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HAD).

Results: The distribution of subtypes was: IBS-diarrhea (IBS-D), 46%; IBS-constipation (IBS-C), 32%, and mixed IBS (IBS-M), 22%. IBS overlap with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), functional dyspepsia, chronic headache and fibromyalgia occurred in 65.5%, 48.7%, 40.7% and 22.1% of patients, respectively. Anxiety and/or depression were found in 81.5%. Comparisons among subgroups showed that bloating was significantly associated with IBS-M compared to IBS-D (odds ratio-OR-5.6). Straining was more likely to be reported by IBS-M (OR 15.3) and IBS-C (OR 12.0) compared to IBS-D patients, while urgency was associated with both IBS-M (OR 19.7) and IBS-D (OR 14.2) compared to IBS-C. In addition, IBS-M patients were more likely to present GERD than IBS-D (OR 6.7) and higher scores for anxiety than IBS-C patients (OR 1.2). BMI values did not differ between IBS-D and IBS-C.

Conclusion: IBS-M is characterized by symptoms frequently reported by both IBS-C (straining) and IBS-D (urgency), higher levels of anxiety, and high prevalence of comorbidities. These features should be considered in the clinical management of this subgroup.

Key words: Irritable bowel syndrome. Mixed-irritable bowel syndrome. Anxiety. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. Constipation. Diarrhea. Dunctional dyspepsia.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional bowel disorder characterized by recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort associated with altered bowel habit (1). Several studies have shown a considerable overlap of IBS with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and functional dyspepsia (FD) (2,3). In addition, nongastrointestinal somatic disorders and psychiatric disorders occur frequently in IBS (4,5). Comorbidity of IBS has been associated with increased use of health resources, impaired quality of life and poor outcome (6).

According to the Rome III criteria IBS is classified into subtypes by predominant stool pattern: IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with constipation (IBS-C) and mixed IBS (IBS-M) (7). Pharmacologic treatment of IBS has been increasingly based on this categorization, but little is known about differences among subtypes regarding co-existent somatic and psychological disorders, which might influence the responses to treatment. The few studies which reported the distribution of IBS subtypes and compared clinical and psychological characteristics between subgroups have shown contradictory results (8-11).

Likewise, the nutritional consequences of chronic diarrhea in IBS-D patients still need clarification (12). Some studies found lower body mass index (BMI) in IBS-D in comparison with the other subtypes (13), while others showed increased BMI in this subgroup (14).

Therefore the aims of the present study were to assess the distribution of subtypes in a group of IBS patients referred to a tertiary center in Brazil, and to investigate whether there are differences among subtypes in clinical, psychological and nutritional features.

Methods

Patients

The study group included 113 consecutive patients (mean age: 48 ± 11 years; females: 94 patients) attending the outpatient gastroenterology clinic of our university hospital with the diagnosis of IBS. IBS was defined according to the Rome III criteria (7). Patients with previous gastrointestinal tract surgery, diabetes mellitus, associated diseases that might cause intestinal dysmotility or in use of medications known to influence gastrointestinal transit were excluded from the study.

Clinical evaluation

A standardized questionnaire was used to obtain information about demographic and clinical data, including the Rome III diagnostic questions for IBS. Symptoms of abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating, flatulence, borborygmus, straining, urgency, and bowel habits were assessed. In addition, characteristics of abdominal pain, such as frequency, location, relationship with food ingestion or defecation were recorded. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms and non-gastrointestinal symptoms, including headache, were also assessed. According to the Bristol stool form scale, IBS patients were divided into: IBS-C, IBS-D and IBS-M, as recommended by Rome III criteria (7).

Upper digestive endoscopy

All patients underwent upper digestive endoscopy in order to identify lesions responsible for esophageal and dyspeptic symptoms. In addition duodenal biopsies were collected to exclude the presence of celiac disease.

Comorbidity of IBS with GERD and FD

GERD was defined by weekly or more frequent typical heartburn or acid regurgitation, and was classified as non-erosive (NERD), in the absence of visible esophageal mucosal injury or erosive esophagitis based on the endoscopic findings (15,16). FD was defined according to Rome III criteria by the presence of at least one of the following symptoms in the last 3 months: bothersome postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain or epigastric burning, with no significant pathological findings at upper endoscopy (17).

Comorbidity with fibromyalgia

The diagnosis of fibromyalgia was performed by a rheumatologist of our university hospital and was based on the American College of Rheumatology criteria (18).

Anxiety and depression

The presence of anxiety and depression was assessed by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale divided into subscales for anxiety and depression (19). The score for each subscale ranges from 0 to 21. Scores higher than 8 in either HAD subscales were considered to indicate anxiety or depression, respectively.

BMI

BMI was calculated for all patients. According to the World Health Organization classification, patients were classified into underweight (BMI < 18.50), overweight (BMI between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2), obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) and normal range (18.50-24.99 kg/m2).

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee. Each patient gave written informed consent before participation in the study.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of the results were performed by the Chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, one way ANOVA and the Kruskal-Wallis test. Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the variables significantly associated with IBS subtypes. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS System for Windows version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., 2002-2012, Cary, NC, USA). A value of p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Clinical features

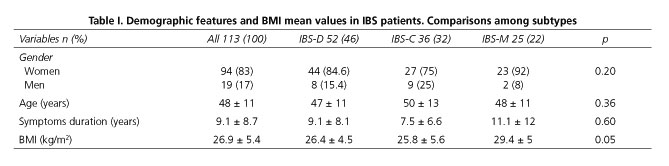

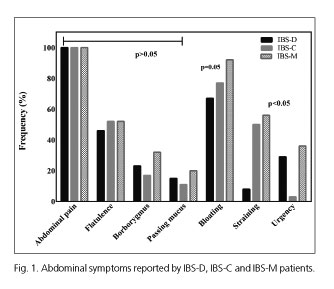

The demographic and baseline symptom profile of IBS patients and the distribution of clinical characteristics among subtypes are summarized in table I and figure 1. It can be seen that there was a preponderance of females (83%) in our series. The most frequent IBS subtype was IBS-D (46%), followed by IBS-C (32%) and IBS-M (22%). No significant differences were found among IBS subtypes in age, gender, symptoms duration and the frequency of borborygmus, passage of mucus and flatulence.

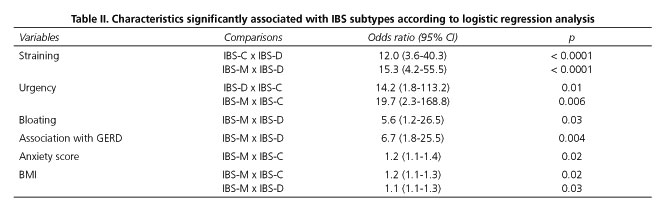

Table II shows the variables significantly associated with IBS subtypes after further analysis using logistic regression analysis. Bloating was reported by 76% of the study group, and was significantly associated with IBS-M in comparison with IBS-D (OD: 5.6; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.2-26.5).

Defecation straining was reported by 32% of IBS patients, and it was significantly associated with both IBS-C (OD: 12.0; 95% CI: 3.6-40.3) and IBS-M (OD: 15.3; 95% CI 4.2-55.5) in comparison with IBS-D. Urgency was associated with IBS-D (OD: 14.2; 95% CI: 1.8-113.2) and IBS-M (OD: 19.7; 95% CI: 2.3-168.8) compared to IBS-C.

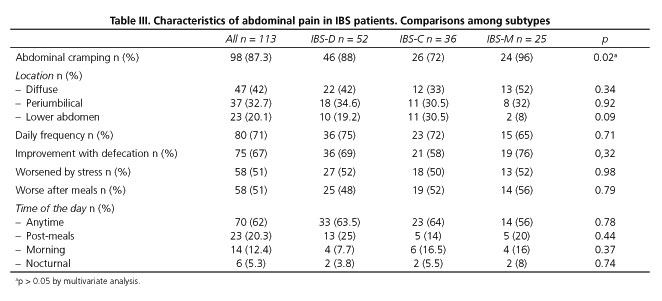

There were no significant differences among IBS subtypes regarding the main characteristics of abdominal pain (Table III). Most patients complained of abdominal cramping at least once a day, which improved with defecation. Abdominal pain was aggravated by stress or meal ingestion in 51% of patients.

Celiac disease

The analysis of duodenal biopsies showed no case of celiac disease in our series.

Overlap with GERD or functional dyspepsia

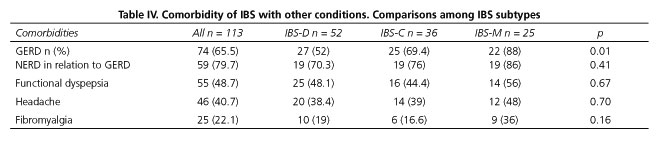

Table IV shows the comorbidity of IBS with other clinical conditions.

Overlap with GERD was observed in 74 IBS patients (65.5%). According to endoscopic evaluation GERD was non-erosive (NERD) in 80% of the cases. Logistic regression analysis showed that IBS-M patients were more likely to present GERD than IBS-D patients (OD: 6.7; 95% CI: 1.8-25.5).

Overlap between IBS and FD occurred in 55 patients (48.7%), with similar frequency in the three subtypes. Postprandial fullness was the most frequent symptom (78%) reported by FD patients.

Headache and fibromyalgia

Chronic headache was reported by 41% of IBS patients, with no significant difference among subtypes. Fibromyalgia was diagnosed in 22% of the study group, with similar frequency in the three subtypes.

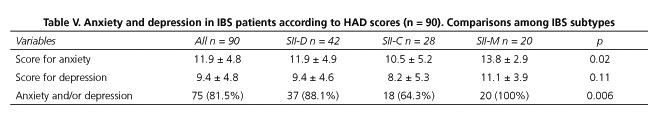

Anxiety and depression

Ninety patients completed the HAD scale. Table V shows the mean scores for anxiety and depression and the frequency of anxiety and/or depression for each subgroup. Overall, 83.3% of IBS patients had anxiety and/or depression according to the scale scores: 47 (52.2%) had anxiety associated with depression, 23 (25.5%) had anxiety and 5 (5.5%) had depression. Comparing IBS patients with or without overlapping FD, there was no significant difference in the scores for anxiety (IBS + FD: 11.3 ± 4.9 vs. 12.5 ± 4.5; p = 0.24) or depression (IBS + FD: 9.9 ± 5.4 vs. 8.9 ± 4.1; p = 0.32). Similarly, there was no significant difference in HAD scores between IBS patients with or without GERD symptoms (p = 0.68).

The comparison among IBS subtypes showed that IBS-M patients were more likely to have higher scores for anxiety (OD: 1.2; 95% CI: 1.1-1.4) than IBS-C patients.

BMI

According to BMI, 31% of IBS patients were classified as overweight and 29% as obese. Two patients were underweight, both belonging to the IBS-C subtype. BMI values were likely to be higher in IBS-M patients in comparison with IBS-C (OD: 1.2; 95% CI: 1.1-1.3) or IBS-D patients (OD: 1.1; 95% CI: 1.1-1.3). No significant difference was found between IBS-C and IBS-D patients regarding BMI values.

Discussion

In the present study the most frequent IBS subtype was IBS-D (46%), followed by IBS-C (32%) and IBS-M (22%). The distribution of IBS subtypes differs in different studies, and probably depends on the population evaluated, geographic location and the definition for each subtype (20). IBS-M was the largest bowel habit subgroup in recent population-based studies performed in UK and the United States (10,21), while IBS-C was the most frequent among Iranian adults (11), and IBS-D the most frequent in tertiary hospitals in China (22). The increased prevalence of IBS-D in our study group may be explained by the fact that all patients were referred from primary care to our gastrointestinal outpatient clinic. General practitioners may be more confident in the management of IBS-C, considering that IBS-D may demand a more complex investigation. Lin et al. (10) found an alternative diagnosis for 21% of patients referred from primary care as IBS-D, while no alternative diagnosis was made for IBS-C. The female predominance in our study group is in agreement with the data from the literature showing female:male ratios of 2:1 to 4:1 (23,24). It has been proposed that this preponderance of women may reflect differences in care-seeking behavior rather than the real incidence (24).

All patients reported abdominal pain which was relieved by evacuation in most cases. Nocturnal pain was rare, in keeping with previous findings in functional gastrointestinal diseases (25). With regard to pain location, our results could not confirm the observations of Bouchoucha et al. (26) showing characteristic sites of pain in IBS-C and IBS-M patients. Our finding that the majority (76%) of IBS patients complained of bloating corroborates that this is a supportive symptom for the diagnosis of IBS which should be taken into account in the therapeutic approach of these patients.

One limitation of the present study is that we did not assess the severity of pain in our patients. Heitkemper et al. (27) have shown that the severity of abdominal pain/discomfort has a stronger effect on the quality of life than altered bowel pattern in IBS female patients. Based on these findings the authors suggested that the categorization of IBS patients should include both abdominal pain/discomfort severity and predominant bowel pattern.

A large proportion of IBS patients were overweight or obese, which is consistent with recent data on the Brazilian population (28). The comparison among subtypes showed no significant difference in BMI values between IBS-D and IBS-C, indicating that chronic diarrhea did not influence the nutritional status of IBS patients. These results are in agreement with those reported by Simrén et al. (29). However, it should be noted that BMI is only one parameter of the nutritional assessment, and further studies are necessary to investigate nutrient intake and specific nutritional deficits in these patients. On the other hand, our finding that about 50% of the study group related the exacerbation of their symptoms with meal ingestion is in agreement with the literature (12), and it reinforces the view that dietary intervention may have a role in the management of IBS.

The excessive comorbidity found in our IBS patients is consistent with the results of previous studies (4-6). The high prevalence of anxiety and depression confirms other reports (5,8,30) and emphasizes the importance of psychological assessment and treatment as part of clinical management of IBS patients. The prevalence of both chronic headache and fibromyalgia was higher than that reported in population studies in Brazil (31,32) and similar to previous findings in IBS patients (5). Likewise, the frequency of overlapping with FD was similar to that previously reported (33). The 65.5% prevalence of GERD is within the range of 11-79% described in other studies (5,34). According to endoscopic evaluation the majority of the cases were classified as NERD, as expected (35). However the present study was unable to confirm the association between comorbidity and psychological distress in IBS, as reported by several authors (5,36). We believe that this may be due to a lack of statistical power to identify differences, given the small number of patients without anxiety or depression in our study population.

The comparisons among IBS subtypes identified some special characteristics of IBS-M subtype. Patients of this subgroup complained of symptoms commonly seen in IBS-C (straining) and IBS-D (urgency), as shown in other studies (21,37). This should be taken into account during treatment with medications with significant effects on colonic motility or stool consistency, which could improve some symptoms, with no relief or even aggravation of others. In addition, IBS-M patients were likely to present higher scores for anxiety, especially in comparison with IBS-C. This is a relevant finding, considering that psychological factors have been previously shown to contribute to poor outcomes, influencing symptoms severity and response to therapy (38). A few studies have compared psychological disturbances among IBS subtypes. Tillisch et al. (39) reported increased psychological comorbidity in IBS-M. Muscatello et al. (9) showed that IBS-C patients were more psychologically distressed than IBS-D. In contrast, Rey de Castro et al. (8) found no difference in anxiety/depression levels among the three subgroups.

Moreover the frequency of GERD was higher in IBS-M patients, particularly when compared to IBS-D. One explanation for this association could be the higher BMI values found in IBS-M patients of our study group, since high BMI has been shown to be a predictor of IBS-GERD overlap (40). An alternative explanation could be the increased levels of anxiety seen in our IBS-M patients, considering that comorbid disorders have been previously related to anxiety and depression in IBS (5).

Taken together, these features indicate that treatment of IBS-M patients may be challenging, as recently suggested by Tillish et al. (39) and Su et al. (41).

In conclusion, IBS-D was the most frequent subtype in IBS patients referred to a tertiary center in Brazil. IBS-M is characterized by symptoms frequently reported by both IBS-C (straining) and IBS-D (urgency), higher levels of anxiety and high prevalence of comorbidities. These particular features require special attention in the therapeutic management of IBS-M patients.

References

1. Drossman DA, Morris CB, Schneck S, et al. International survey of patients with IBS: Symptom features and their severity, health status, treatments, and risk taking to achieve clinical benefit. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009;43:541-50. DOI: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318189a7f9. [ Links ]

2. Nastaskin I, Mehdikhani E, Conklin J, et al. Studying the overlap between IBS and GERD: A systematic review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci 2006;51:2113-20. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-006-9306-y. [ Links ]

3. Piacentino D, Cantarini R, Alfonsi M, et al. Psychopathological features of irritable bowel syndrome patients with and without functional dyspepsia: A cross sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol 2011;11:94. DOI: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-94. [ Links ]

4. Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Henningsen P. Irritable bowel syndrome: Relations with functional, mental, and somatoform disorders. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:6024-30. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i20.6024. [ Links ]

5. Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: What are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology 2002;122:1140-56. [ Links ]

6. Vandvik PO, Wilhelmsen I, Ihlebaek C, et al. Comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: A striking feature with clinical implications. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20:1195-203. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02250.x. [ Links ]

7. Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480-91. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [ Links ]

8. Rey de Castro NG, Miller V, Carruthers HR, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: A comparison of subtypes. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;30:279-85. DOI: 10.1111/jgh.12704. [ Links ]

9. Muscatello MR, Bruno A, Pandolfo G, et al. Depression, anxiety and anger in subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome patients. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2010;17:64-70. DOI: 10.1007/s10880-009-9182-7. [ Links ]

10. Lin S, Mooney PD, Kurien M, et al. Prevalence, investigational pathways and diagnostic outcomes in differing irritable bowel syndrome subtypes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;26:1176-80. DOI: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000171. [ Links ]

11. Keshteli AH, Dehestani B, Daghaghzadeh H, et al. Epidemiological features of irritable bowel syndrome and its subtypes among Iranian adults. Ann Gastroenterol 2015;28:253-8. [ Links ]

12. Gorospe EC, Oxentenko AS. Nutritional consequences of chronic diarrhoea. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2012;26:663-75. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpg.2012.11.003. [ Links ]

13. Kubo M, Fujiwara Y, Shiba M, et al. Differences between risk factors among irritable bowel syndrome subtypes in Japanese adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011;23:249-54. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01640.x. [ Links ]

14. Sadik R, Björnsson E, Simrén M. The relationship between symptoms, body mass index, gastrointestinal transit and stool frequency in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;22:102-8. DOI: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32832ffd9b. [ Links ]

15. Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: Clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut 1999;45:172-80. DOI: 10.1136/gut.45.2.172. [ Links ]

16. Fass R, Fennerty MB, Vakil N. Nonerosive reflux disease-current concepts and dilemmas. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:303-14. [ Links ]

17. Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1466-79. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.059. [ Links ]

18. Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:600-10. DOI: 10.1002/acr.20140. [ Links ]

19. Botega NJ, Bio MR, Zomignani MA, et al. Mood disorders among inpatients in ambulatory and validation of the anxiety and depression scale HAD. Rev Saude Publica 1995;29:355-63. [ Links ]

20. Quigley EM, Bytzer P, Jones R, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: The burden and unmet needs in Europe. Dig Liver Dis 2006;38:717-23. DOI: 10.1016/j.dld.2006.05.009. [ Links ]

21. Su AM, Shih W, Presson AP, et al. Characterization of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome with mixed bowel habit pattern. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26:36-45. DOI: 10.1111/nmo.12220. [ Links ]

22. Yao X, Yang YS, Cui LH, et al. Subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome on Rome III criteria: A multicenter study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27:760-5. DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06930.x. [ Links ]

23. Chial HJ, Camilleri M. Gender differences in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gend Specif Med 2002;5:37-45. [ Links ]

24. Canavan C, West J, Card T. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Epidemiol 2014;6:71-80. [ Links ]

25. Gunnarsson J, Simrén M. Efficient diagnosis of suspected functional bowel disorders. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;5:498-507. DOI: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1203. [ Links ]

26. Bouchoucha M, Fysekidis M, Devroede G, et al. Abdominal pain localization is associated with non-diarrheic Rome III functional gastrointestinal disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2013;25:686-93. DOI: 10.1111/nmo.12149. [ Links ]

27. Heitkemper M, Cain KC, Shulman R, et al. Subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome based on abdominal pain/discomfort severity and bowel pattern. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:2050-8. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-011-1567-4. [ Links ]

28. Brasil estabiliza taxas de sobrepeso e obesidade (Portal Brasil web site). April 30, 2014. Available at: http://www.brasil.gov.br/saude/2014/04/brasil-estabiliza-taxas-de-sobrepeso-e-obesidade. Accessed November 7, 2014. [ Links ]

29. Simrén M, Månsson A, Langkilde AM, et al. Food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion 2001;63:108-15. DOI: 10.1159/000051878. [ Links ]

30. Fond G, Loundou A, Hamdani N, et al. Anxiety and depression comorbidities in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2014;264:651-60. DOI: 10.1007/s00406-014-0502-z. [ Links ]

31. Bigal ME, Bordini CA, Speciali JG. Etiology and distribution of headaches in two Brazilian primary care units. Headache 2000;40:241-7. DOI: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00035.x. [ Links ]

32. Senna ER, De Barros AL, Silva EO, et al. Prevalence of rheumatic diseases in Brazil: A study using the COPCORD approach. J Rheumatol 2004;31:594-7. [ Links ]

33. Talley NJ, Dennis EH, Schettler-Duncan VA, et al. Overlapping upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients with constipation or diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:2454-9. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07699.x. [ Links ]

34. Gasiorowska A, Poh CH, Fass R. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) - Is it one disease or an overlap of two disorders? Dig Dis Sci 2009;54:1829-34. [ Links ]

35. Noh YW, Jung HK, Kim SE, et al. Overlap of erosive and non-erosive reflux diseases with functional gastrointestinal disorders according to Rome III criteria. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010;16:148-56. DOI: 10.5056/jnm.2010.16.2.148. [ Links ]

36. Vandvik PO, Wilhelmsen I, Ihlebaek C, et al. Comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: A striking feature with clinical implications. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20:1195-203. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02250.x. [ Links ]

37. Mearin F, Balboa A, Badía X, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome subtypes according to bowel habit: Revisiting the alternating subtype. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;15:165-72 . DOI: 10.1097/00042737-200302000-00010. [ Links ]

38. Creed F, Ratcliffe J, Fernandes L, et al. North of England IBS Research Group. Outcome in severe irritable bowel syndrome with and without accompanying depressive, panic and neurasthenic disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2005;186:507-15. DOI: 10.1192/bjp.186.6.507. [ Links ]

39. Tillisch K, Labus JS, Naliboff BD, et al. Characterization of the alternating bowel habit subtype in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:896-904. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41211.x. [ Links ]

40. Jung HK, Halder S, McNally M, et al. Overlap of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and irritable bowel syndrome: Prevalence and risk factors in the general population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;26:453-61. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03366.x. [ Links ]

41. Su AM, Shih W, Presson AP, et al. Characterization of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome with mixed bowel habit pattern. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26:36-45. DOI: 10.1111/nmo.12220. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Cristiane Kibune Nagasako and Maria Aparecida Mesquita.

Gastroenterology Unit,

Department of Clinical Medicine.

Universidade Estadual de Campinas-Unicamp.

Rua Tessália Vieira de Camargo, 126.

Cidade Universitária "Zeferino Vaz".

13083-887 Campinas. São Paulo, Brazil

e-mail: crisknvc@gmail.com

Received: 20-08-2015

Accepted: 15-11-2015