Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.108 no.4 Madrid abr. 2016

Sensitivity and specificity of the Gastrointestinal Short Form Questionnaire in diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease

Sensibilidad y especificidad del Cuestionario Gastrointestinal Corto en el diagnóstico de la enfermedad por reflujo gastroesofágico

Carlos Teruel-Sánchez-Vegazo1, Vicenta Faro-Leal1, Alfonso Muriel-García2 and Norberto Mañas-Gallardo3

Departments of 1 Gastroenterology and 2 Biostatistics. Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal. Madrid, Spain.

3 Service of Gastroenterology. Hospital Madrid Norte Sanchinarro. Madrid, Spain

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Gastrointestinal Short Form Questionnaire (GSFQ) is a questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) diagnosis, with a version in Spanish language, not yet compared to an objective test.

Aims: To establish GSFQ diagnostic performance against 24-hour pH monitoring carried out in two tertiary care hospitals.

Methods: Consecutive adult patients with typical GERD symptoms (heartburn, regurgitation) referred for pH monitoring fulfilled the GSFQ (score range 0-30, proportional to probability of GERD). Diagnosis of GERD was established when acid exposure time in distal esophagus was superior to 4.5% or symptom association probability was greater than 95%. Receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) curves were calculated and best cut-off score determined, with corresponding sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratios (LR) (95% confidence interval for each).

Results: One hundred and fifty-two patients were included (59.9% women, age 47.9 ± 13.9; 97.4% heartburn; 71.3% regurgitation). pH monitoring was abnormal in 65.8%. Mean GSFQ score was 11.2 ± 6. Area under ROC was 56.5% (47.0-65.9%). Optimal cut-off score was 13 or greater: sensitivity 40% (30.3-50.3%), specificity 71.2% (56.9-82.9%), positive LR 1.39 (0.85-2.26) and negative LR 0.84 (0.67-1.07). Exclusion of questions 1 and 3 of the original GSFQ, easily interpreted as referred to dyspepsia and not GERD, improved only marginally the diagnostic performance: AUROC 59.1%.

Conclusion: The GSFQ does not predict results of pH monitoring in patients with typical symptoms in a tertiary care setting.

Key words: Gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ambulatory pH monitoring. Sensitivity. Specificity.

RESUMEN

Introducción: el Cuestionario Gastrointestinal Corto (GSFQ) es un cuestionario diseñado para el diagnóstico de enfermedad por reflujo gastroesofágico (ERGE), con versión en español. No ha sido comparado con una prueba diagnóstica objetiva.

Objetivos: determinar el poder diagnóstico del GSFQ usando como referencia la pH-metría de 24 horas en dos hospitales de tercer nivel.

Métodos: pacientes adultos consecutivos con síntomas típicos de ERGE (pirosis, regurgitación), a los que se solicita pH-metría, rellenaron el GSFQ (rango puntuación 0-30, proporcional a probabilidad de ERGE). Se estableció el diagnóstico de ERGE cuando la exposición ácida del esófago distal fue superior a 4,5% o cuando la probabilidad de asociación sintomática fue superior al 95%. Se calcularon curvas ROC (receiver operator characteristic) y se determinó el mejor punto de corte, con sus correspondientes sensibilidad, especificidad y ratios de probabilidad (LR) (intervalo de confianza del 95% para cada determinación).

Resultados: se incluyeron 152 pacientes (59,9% mujeres; edad 47,9 ± 13,9; 97,4% pirosis; 71,3% regurgitación). La pH-metría fue patológica en el 65,8%. La puntuación media del GSFQ fue 11,2 ± 6. El área bajo la curva ROC fue 56,5% (47-65,9%). El punto de corte óptimo fue 13 o mayor: sensibilidad 40% (30,3-50,3%), especificidad 71,2% (56,9-82,9%), LR positiva 1,39 (0,85-2,26) y LR negativa 0,84 (0,67-1,07). Excluir las preguntas 1 y 3 del GSFQ, referidas a síntomas parecidos a los de la dispepsia, mejoró sólo marginalmente el poder diagnóstico (AUROC 59,1%).

Conclusión: el GSFQ no predice los resultados de la pH-metría en pacientes con síntomas típicos de ERGE en un entorno de hospital terciario.

Palabras clave: Enfermedad por reflujo gastroesofágico. pH-metría ambulatoria. Sensibilidad. Especificidad.

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is defined by the Montreal consensus as the troublesome signs and symptoms caused by reflux of gastric content (1). It is one of the most prevalent gastrointestinal diseases worldwide, with an estimated prevalence of 10-20% in Western countries, 15% in Spanish adult population (2,3). GERD impacts quality of life and causes an important economic burden to health-care systems due to over-the-counter or prescribed medication, diagnostic procedures and work absenteeism (4,5).

In spite of such prevalence its diagnosis still supposes a challenge in many cases, as many patients suffer from atypical symptoms (chronic cough, asthma, laryngitis, etc.) and there is no gold standard test that can serve as a universal reference. Typical symptoms, heartburn and regurgitation, do not correlate well with objective findings in endoscopy (erosive esophagitis or Barrett metaplasia) or in pH monitoring tests, as it does not the response to a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) test (6-8). On top of that, pH monitoring, theoretically the most reliable diagnostic test, is expensive, not widely available and its performance is usually not optimal as false negative results are frequent (9). To overcome these difficulties in diagnosing GERD, in the past two decades several questionnaires have been developed to diagnose it, to quantify its severity and to monitor response to treatment. In fact, they are frequently used as outcome measures in many randomized control trials (10). Most of them have either not been compared to other diagnostic tests such as endoscopy or pH monitoring or have a poor specificity when they have been (8,10). The most studied one, the Gastroesophageal Disease Questionnaire (GerdQ), has fine sensitivity and specificity, and a management strategy based on its application in primary care has proven to be as useful, and even cheaper, as the classical approach based on endoscopy and pH monitoring (11-14).

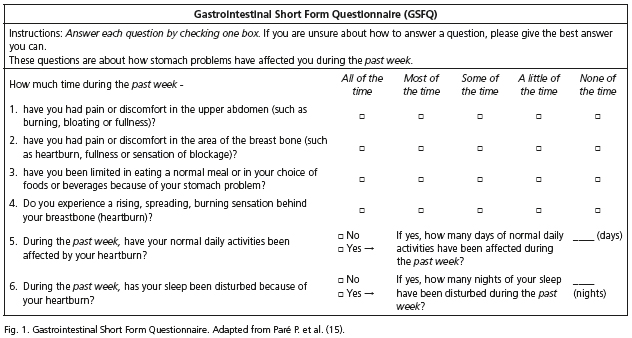

In this context, in 2003 a Canadian group developed the Gastrointestinal Short Form Questionnaire (GSFQ), a self-administered 6-item symptom-frequency survey (15). Although not widely used, it is very easy to fulfill and is one of the few available GERD questionnaires with a validated Spanish version (16). Not compared yet with an objective diagnostic test for GERD to our knowledge, it has a potential utility in GERD diagnosis in our setting. The objective of the present study is to compare GSFQ scores with the results of ambulatory 24 hour pH monitoring and determine if this diagnostic tool could have a place in clinical management of GERD patients. The main hypothesis is that higher scores will correlate most with the probability of a pathological result of the pH monitoring.

Material and Methods

Patients

Consecutive adult patients referred to the Gastrointestinal Motility units of the two participating hospitals in Madrid, Spain, between January 2012 and December 2013 to undergo 24-hour pH monitoring because of suspicion of GERD due to typical symptoms (heartburn and/or regurgitation) were asked to participate. We excluded those with alarm symptoms (anemia, unintentional weight loss, progressive dysphagia or signs of gastrointestinal bleeding), those with previous anti-reflux surgery and those who could not understand the language well enough to be able to fulfill the questionnaire. Coexistence of chest pain or extraesophageal symptoms was allowed, but we excluded those patients whose dominant symptom was not heartburn or regurgitation and those who had chest pain or extraesophageal symptoms exclusively. All patients gave written informed consent.

Ambulatory pH monitoring

After an overnight fast and after withdrawing PPI or H2 antagonists for at least 7 and 4 days respectively (studies off medication), a pH monitoring probe (Versaflex® and Geroflex®, Given Imaging) was placed transnasally fixing the transducer 5 cm above the upper border of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) as localized with previous esophageal manometry. Data was recorded digitally (Digitrapper Mark III®, Synectics; Digitrapper PH400®, Medtronic; Digitrapper PHZ®, Given Imaging) and analyzed with dedicated software (Polygram®, Gastrotrac® and Accuview® respectively). Patients were instructed to follow their daily routines normally including their normal diet, to avoid any drug that could alter normal gastric acidity and to register meal and recumbent periods as well as any heartburn or regurgitation events they felt during the study period.

All patients underwent an esophageal manometry at least to localize the upper border or the LES. Complete manometry was carried out only if it was requested by the referring physician. It was performed using 4 lumen water-perfused catheters (MUI Scientific) connected to a polygraph and analyzed with dedicated software (Polygram® or Gastrotrac®). LES basal pressure was determined as the mean maximal expiratory pressure referred to gastric basal pressure registered with all four sensors using a pull-through technique. Esophageal body peristalsis was explored placing the sensors 3, 8, 13 and 18 cm above the upper LES border and administering 10 swallows of 5 ml of tap water separated at least 20 seconds each. Weak peristalsis was defined as the occurrence of 30% or more of weak (mean amplitude in the two distal channels less than 30 mmHg) or interrupted waves. Diffuse esophageal spasm was defined as the occurrence of 20% or more of simultaneous contractions with amplitude higher than 30 mmHg. Hypertensive peristalsis was defined as the occurrence of a mean peristaltic wave amplitude in the two distal channels higher than 180 mmHg.

Results of pH monitoring and manometry were interpreted by authors CT, VF and NM, all experienced in performance of esophageal function tests.

The 24-hour pH monitoring was considered diagnostic of GERD if esophageal acid exposure time (AET) was higher than 4.5% of total recorded time or if AET was < 4.5% but symptoms (regurgitation or heartburn) were significantly associated with the occurrence of acid reflux episodes (hypersensitive esophagus). Symptom-reflux association was analyzed using the Symptom Association Probability (SAP), a statistical test in which the pH study is divided in 2 minutes intervals and presence or absence of reflux and symptomatic events is counted. A 2 x 2 table is generated and a two-tailed Fisher's exact test applied. SAP > 95% (p < 0.05) indicates a significant, not random, association between symptoms and reflux episodes (17). Only patients that presented three or more events of the same type (heartburn or regurgitation) were considered for symptom-reflux association analysis. If a patient presented three or more episodes of heartburn and three or more episodes of regurgitation, the symptom-reflux association was considered positive if SAP was higher than 95% for at least one of them. Extraesophageal symptoms patients reported were not considered for the analysis.

GSFQ fulfillment

Patients were asked to read and complete the questionnaire (Fig. 1) before placement of the pH monitoring catheter. Any doubts they had were solved. The questionnaire refers to the previous week and includes six items, 4 about frequency of occurrence of several symptoms and interference with diet and daily activities, and two about the number of days or nights in the previous week in which daily activities or sleep respectively were disturbed by GERD symptoms. The first four items are scored using a Lickert scale (0 none of the time, 4 all of the time) while the last two are scored with one point for each day or night affected (0 none, 7 all days or nights in the previous week), to make a composite score that ranges from 0 (no reflux) to 30 (maximal clinical disturbance due to reflux symptoms).

Other diagnostic procedures

If patients had undergone an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) prior to pH monitoring, its result was registered, namely the presence of erosive esophagitis, graded with the Los Angeles classification (18), or Barrett esophagus.

GSFQ diagnostic power determination

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves and their 95% confidence interval were used to calculate optimum cut-off values (maximal trade-off between sensitivity and specificity) to evaluate the ability of the GSFQ to discriminate between patients with and without objectively measured acid reflux in the pH monitoring study as defined previously (total AET > 4.5% or positive symptom-reflux association). We estimated sensitivities, specificities, positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR+ and LR- respectively) and the area under the curve (AUROC). Additionally, we estimated the same parameters using the GSFQ score of 12 or more, which was reported by Ruiz-Díaz MA, et al. as the optimal cut-off value, with an estimated sensitivity of 60.5% and specificity of 68.3% (16).

On the other hand, questions 1 and 3 of the GSFQ refer to symptoms localized in the "upper abdomen" or "stomach", so dyspeptic symptoms and no proper GERD symptoms could be referred to by patients when answering these questions, underpowering thus the questionnaire's ability to diagnose GERD. In view of this a priori assumption, we performed a second diagnostic analysis of the GSFQ excluding those two questions to ascertain if the remaining four had indeed a diagnostic power that was undermined when scoring the questionnaire including all 6 questions as originally conceived. In this "short version" of the GSFQ the maximum score would be 22. We finally carried out a sub-analysis including as patients with objective GERD also those who had undergone an EGD, had normal pH monitoring parameters but presented peptic esophagitis.

Sample size was estimated presuming a GERD prevalence of 54% (obtained by reviewing results of all pH monitoring carried out in the previous 3 months in the participating units), a required sensitivity of 95 ± 5% and an alpha error of 0.05. We obtained a number of 146 subjects. Assuming a 10% of losses attributable to technical problems in data acquisition or any other circumstances that could avoid a reliable analysis of the pH monitoring, a final sample size of 160 was established.

Data are expressed for quantitative variables as mean and standard deviation when normally distributed or as median and range when not, and as proportions for qualitative variables with corresponding 95% confidence intervals when suitable. All test results with a p value < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were completed using STATA version 13.1 (StataCorp).

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Clinical Investigation Ethical Board of both participating centers.

Results

Characteristics of patients

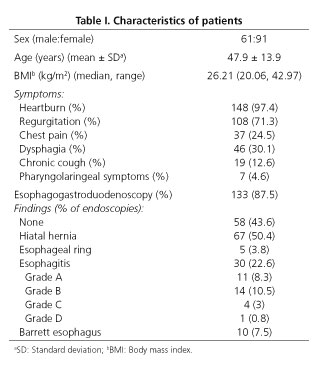

A total of 160 patients were included. Eight were finally excluded because of technical failure during pH monitoring that avoided an optimal and confident analysis of the results. Characteristics of the remaining 152 are described in table I.

Patients complained of heartburn (97.4%) or regurgitation (71.3%) as their main symptom, alone or in combination with the other symptoms detailed in table I.

Endoscopic findings

Of the 152 patients who entered the study, 133 had undergone EGD before pH monitoring (Table I). The endoscopy revealed no relevant findings in 43.6%, hiatal hernia in 50.4%, esophageal ring in 3.8%, esophagitis in 22.6% (grade A, 8.3%; grade B, 10.5%; grade C, 3% and grade D, 0.8%) and Barrett esophagus in 7.5%.

Manometrical findings

Esophageal manometry was carried out in 133 patients. Weak peristalsis was detected in 41 of them (30.8%), hypertensive peristalsis in 3 (2.3%) and unspecified motor disorder in 1 (0.8%). LES median (range) resting pressure was 10 mmHg (3,36).

pH recordings

The median (range) percent of total AET was 6.6% (0.1, 48). Abnormal AET was noted in 94 patients (61.8%). Of the remaining patients with normal AET, 32 registered symptoms. Six of them had at least three symptoms and scored a positive SAP. Therefore, a total of 100 patients (65.8%) had an objective diagnosis of GERD by pH monitoring.

GSFQ scores

The mean (sd) GSFQ score was 11.2 (6.0). The AUROC was 56.5% (95% CI: 47.0-65.9%), which indicates that GSFQ scores do not make a statistically significant discrimination between normal and pathological acid reflux (AUROC of 50% indicates that the test is not better than a coin toss in determining whether the disease is present or not). Optimal cut-off value was 13 or higher, with a sensibility of 40.0% (95% CI: 30.3-50.3%), a specificity of 71.2% (95% CI: 56.9-82.9%), a LR+ of 1.39 (95% CI: 0.85-2.26) and a LR- of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.67-1.07). For the 12 points cut-off value proposed by Ruiz-Díaz MA, et al. (16), the numbers were worse: sensitivity 47.0%, specificity 55.8%, LR+ 1.06 and LR- 0.95.

Of the 133 patients who had undergone an EGD, 93 had pathological pH monitoring (30 had also esophagitis) and 5 had esophagitis with normal pH recordings. Adding these together we obtained a total of 98 patients (73.7% of the 133) who had objective signs of GERD as defined in a post-hoc analysis. Using this as new gold standard we obtained an AUROC of 59.0% (95% CI: 48.7-69.3%) with an optimal cut-off score of 13 or more for a sensitivity of 39.8% (95% CI: 29.8-50.5%), a specificity of 82.5% (95% CI: 67.2-92.7%), a LR+ of 2.27 (95% CI: 1.11-4.66) and a LR- of 0.73 (95% CI: 0.59-0.91).

Exclusion of questions 1 and 3 improved diagnostic power minimally, obtaining an AUROC of 59.1% (49.7-68.5%). In the "short version" of the questionnaire (score range 0-22) the optimal cut off value was 9 or higher, with a sensitivity of 34.0% (95% CI: 24.8-44.2%), specificity of 82.7% (95% CI: 69.7-91.8%), a LR+ of 1.96 (95% CI: 1.02-3.78) and LR- of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.66-0.96). When we analyzed only the 133 patients with EGD, AUROC for the "short version" was 53.9% (95% CI: 43.4-64.4%). This time the optimal cut-off value was 8 or higher, with a sensitivity of 36.6% (95% CI: 26.8-47.23%), a specificity of 77.5% (95% CI: 61.5-89.2%), a LR+ of 1.62 (95% CI: 0.86-3.06) and a LR- of 0.82 (95% CI: 0.65-1.03).

In table II we summarize all diagnostic power analysis of GSFQ we have performed.

Discussion

GERD is a highly prevalent disease with which not only gastroenterologists but also primary care physicians have to deal with. In spite of its prevalence and relatively straightforward pathophysiology, making a precise diagnosis is sometimes a challenge, especially when we face patients we believe suffer from GERD but do not respond to PPI, the best medical option, or when we are considering anti-reflux surgery.

Invasive tests, mainly EGD and 24 hour pH monitoring, offer the most potent diagnostic capacity based on their high specificity: if a patient has peptic esophagitis or a pathological acid exposure time, that patient has indeed GERD. However, these tests are uncomfortable, expensive and their sensitivity can be disappointing. EGD is frequently normal (up to 50% of cases) in patients with typical symptoms, being unable to distinguish between non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) or functional heartburn (8,9), and up to a third of patients with established disease as defined by the presence of peptic esophagitis that undergo pH monitoring have normal pH monitoring parameters (9,11).

Most physicians will manage GERD patients initially on a purely clinical workout basis. Indeed, recent guidelines recommend treating directly with PPIs those patients that have typical symptoms and no alarm signs (19). However, several studies have pointed out that basing diagnosis of GERD on the sole presence or absence of these symptoms is very inaccurate, with low sensitivity and slightly better specificity (6,8,20). The PPI test is also imperfect, with acceptable sensitivities but low specificities as functional heartburn can respond to PPI (7,19,21).

In view of these difficulties, several groups have developed in the last two decades different questionnaires to enhance symptom-based GERD, to quantify its severity and even monitor responsiveness to treatment. Most are self-administered by the patient as subjective symptomatic control is the main objective in most cases, and only a few have been extensively studied and compared with the most potent invasive diagnostic tests (endoscopy and pH monitoring). Of them, GerdQ is the most studied. Developed as an exploratory part of the DIAMOND study, this simple self administered 6-item questionnaire showed a fair diagnostic accuracy when compared to diagnosis of GERD made by EGD, pH-monitoring or response to PPI treatment if AET in pH-monitoring was borderline, with a sensitivity of 65%, specificity of 71% and positive predictive value (PPV) of 80% using a cut-off value of 8 or higher (range 0-18) (11,12). These results were reproduced in later studies (22). Two recent European multicentre prospective studies concluded that patient management based on GerdQ score was not only non-inferior in achieving patient satisfaction but also cheaper than a more classical strategy, based on prompter EGD and pH monitoring (13,14). Patients with no alarm features and high GerdQ scores should be prescribed PPI confidently, while invasive tests (EGD and pH monitoring) would be reserved for those with low scores.

GSFQ is a similar questionnaire (self-administered, simple, 6-item based) of which we have a validated translated version in Spanish, and could perform as good or better than GerdQ in aiding gastroenterologists and primary care practitioners in GERD bench-side diagnosis and management. We designed the present study to analyze its diagnosis power using a 24 hour pH monitoring as gold standard. Results indicate however that GSFQ does not perform significantly better than chance in discriminating patients with objective GERD from those without. In a post hoc analysis we expanded the gold standard diagnosis criteria using EGD results to avoid potential pH monitoring false negatives, but sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratios were similar.

GSFQ questions 1 and 3 refer to vaguely described symptoms localized in the upper abdomen that could be easily referred to by patients with dyspeptic and not GERD symptoms. Actually, the investigators that elaborated the GerdQ took into account this GERD-dyspepsia dichotomy and introduced in the final version of the questionnaire two questions that referred to typical dyspeptic symptoms, giving them a negative value, so that patients that reported those symptoms were interpreted as having less probably GERD (12). We decided consequently to make a sub-analysis omitting questions 1 and 3 to determine if exclusion of this possible confusion element would enhance the diagnostic capacity of the questionnaire indeed. The "short version" however did not achieve a significantly better diagnostic performance.

The present study has several disadvantages. First of all, establishing pH monitoring as the unique gold standard means that false negative results could diminish GSFQ real power. We tried to overcome this difficulty expanding the parameters that define objective GERD, so not only a high AET defined GERD but also a positive symptom-reflux association as determined by SAP, a criterion widely used in similar studies (11-14). We were stricter than others in determining a positive association as we required a presence of at least three symptomatic episodes. It has been shown that with a lower number of symptoms SAP performance is less consistent (23). We did not use impedance monitoring, what could have also increased false negatives as non-acidic reflux remained undetected. However, pH-impedance monitoring performs better than conventional pH monitoring mainly when studies are undertaken "on treatment" with PPI, as non-acidic refluxes become predominant in such conditions (24). Besides, 24-hour pH monitoring is much more available in our setting than pH-impedance studies, so we consider that exploring GSFQ diagnostic power against it is of interest. We point out in any case that 65.8% of patients in the present study had objective GERD as determined by pH monitoring (73.7% when adding esophagitis with normal pH-metry), a much higher proportion than that initially estimated, what makes us consider that probably the false negative rate is not high anyhow.

Another drawback is that both participating units belong to tertiary hospitals, where patients are not representative of usual primary care patients. In our setting the proportion of PPI-refractoriness, functional heartburn and concurrence of atypical symptoms is presumably higher. We cannot therefore extrapolate our results to a primary care population having "upper digestive symptoms" (analog to that where GerdQ was tested), in which it is possible that the questionnaire yielded a better diagnostic performance. From this point of view, our study is in our opinion comparable to that of Lacy BE, et al., which compared GerdQ to 48 hour pH monitoring carried out in a tertiary hospital. Their results were, noticeably, very similar to ours (AUROC 61%, sensitivity 43%, specificity 75%) (25). In any case, the high specificity we detect could anyhow make GSFQ useful in a diagnostic strategy similar to that tested for GerdQ by Jonasson C, et al. and Berquist H, et al. (13,14) (patients with high scores will be treated and those with low scores will be tested further). This hypothesis should be explored in specifically designed future studies, preferably in primary care settings.

In light of these results we conclude that GSFQ as originally designed is not a useful tool in a tertiary care setting for diagnosing GERD as defined by 24-hour pH monitoring. We believe that any GERD questionnaire should be tested against the most objective diagnostic tools (mainly pH monitoring with or without impedance) to establish its real diagnostic precision before one could recommend its widespread use.

References

1. Vakil N, Van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, et al. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: A global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1900-20. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. [ Links ]

2. Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, et al. Epidemiology of gastrooesophageal reflux disease: A systematic review. Gut 2005;54:710-7. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2004.051821. [ Links ]

3. Ponce J, Vegazo O, Beltrán B, et al. Prevalence of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in Spain and associated factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;23:175-84. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02733.x. [ Links ]

4. Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology 2002; 122:1500-11. DOI: 10.1053/gast.2002.32978. [ Links ]

5. Rey E, Moreno-Elola-Olaso C, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Impact of gastroesophageal symptoms on health resource usage and work absenteeism in Spain. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2006;98:518-26. DOI: 10.4321/S1130-01082006000700005. [ Links ]

6. Moayyedi P, Axon ATR. The usefulness of the likelihood ratio in the diagnosis of dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:3122-5. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01502.x. [ Links ]

7. Numans ME, Lau J, De Wit NJ, et al. Short-term treatment with proton-pump inhibitors as a test for gastroesophageal reflux disease: A meta-analysis of diagnostic test characteristics. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140:518-27. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00011. [ Links ]

8. Lacy BE, Weiser K, Chertoff J, et al. The diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Med 2010;123:583-92. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.01.007. [ Links ]

9. Vakil N. The initial diagnosis of GERD. Bes Prac Res Clin Gastroenterol 2013;27:365-71. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.06.007. [ Links ]

10. Vakil N, Halling K, Becher A, et al. Systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments for gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;25:2-14. DOI: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328358bf74. [ Links ]

11. Dent J, Vakil N, Jones R, et al. Accuracy of the diagnosis of GORD by questionnaire, physicians and a trial of proton pump inhibitor treatment: The Diamond Study. Gut 2010;59:714-21. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2009.200063. [ Links ]

12. Jones R, Junghard O, Dent J, et al. Development of the GerdQ, a tool for the diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Alim Pharmacol Ther 2009;30:1030-8. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04142.x. [ Links ]

13. Jonasson C, Moum B, Bang C, et al. Randomised clinical trial: A comparison between a GerdQ-based algorithm and an endoscopy-based approach for the diagnosis and initial treatment of GERD. Alim Parmacol Ther 2012;35:1290-300. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05092.x. [ Links ]

14. Berquist H, Agreus L, Tillander L, et al. Structured diagnostic and treatment versus the usual primary care approach in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47:e65-e73. [ Links ]

15. Pare P, Meyer F, Armstrong D, et al. Validation of the GSFQ, a self-administered symptom frequency questionnaire for patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Can J Gastroenterol 2003;17:307-12. [ Links ]

16. Ruiz-Díaz MA, Suárez-Parga JM, Pardo A, et al. Adaptación cultural al español y validación de la escala GSFQ (Gastrointestinal Short Form Questionnaire). Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;32:9-21. DOI: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2008.09.006. [ Links ]

17. Weusten NL, Roelofs JM, Akkermans LM, et al. The symptom-association probability: An improved method for symptom analysis of 24-hour esophageal pH data. Gastroenterology 1994;107:1741-5. [ Links ]

18. Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: Clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut 1999;45:172-80. DOI: 10.1136/gut.45.2.172. [ Links ]

19. Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:308-28. DOI: 10.1038/ajg.2012.444. [ Links ]

20. Moayyedi P, Talley NJ, Fennerty MB, et al. Can the clinical history distinguish between organic and functional dyspepsia? JAMA 2006; 295:1566-76. [ Links ]

21. Bytzer P, Jones R, Vakil N, et al. Limited ability of the proton-pump inhibitor test to identify patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:1360-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.06.030. [ Links ]

22. Jonasson C, Wernersson B, Of DA, et al. Validation of the GerdQ questionnaire for the diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:564-72. DOI: 10.1111/apt.12204. [ Links ]

23. Kushnir VM, Sathyamurthy A, Drapekin J, et al. Assessment of concordance of symptom reflux association tests in ambulatory pH monitoring. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012;35:1080-7. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05066.x. [ Links ]

24. Bredenoord AJ, Tutuian R, Smout A, et al. Technology review: Esophageal impedance monitoring. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:187-94. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00966.x. [ Links ]

25. Lacy BE, Chehade R, Crowell MD. A prospective study to compare a symptom-based reflux disease questionnaire to 48-h wireless pH monitoring for the identification of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1064-71. DOI: 10.1038/ajg.2011.180ss. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Carlos Teruel.

Department of Gastroenterology.

Hospital Ramón y Cajal.

Ctra. de Colmenar Viejo, km 9,1.

28034 Madrid, Spain

e-mail: cteruelvegazo@yahoo.es

Received: 07-11-2015

Accepted: 20-12-2015

texto en

texto en