Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.108 no.9 Madrid sep. 2016

https://dx.doi.org/10.17235/reed.2016.4447/2016

DOI: 10.17235/reed.2016.4447/2016

ORIGINAL PAPERS

Previous exposure to biologics and C-reactive protein are associated with the response to tacrolimus in inflammatory bowel disease

Iago Rodríguez-Lago1,6, Olga Merino2,6, Óscar Nantes3,6, Carmen Muñoz4,6, Urko Aguirre5 and José Luis Cabriada1,6, on behalf of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study Group from the Basque-Navarre Society of Gastrointestinal Diseases

1Gastroenterology Department. Hospital de Galdakao. Galdakao, Vizcaya. Spain.

2Gastroenterology Department. Hospital Universitario de Cruces. Barakaldo, Vizcaya. Spain.

3Gastroenterology Department. Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra. Pamplona, Navarra. Spain.

4Gastroenterology Department. Hospital Universitario de Basurto. Bilbao, Vizcaya. Spain.

5Research Unit. Hospital de Galdakao. Galdakao, Vizcaya. Spain. Health Services Research on Chronic Patients Network (REDISSEC).

6Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study Group from the Basque-Navarre Society of Gastrointestinal Diseases

Conference presentation: the Results of this study have been presented in the UEG Week 2014, AEG 2015, ECCO Congress 2015, AEG 2016 and ECCO Congress 2016.

This work was supported by the Research Commission of Hospital de Galdakao.

ABSTRACT

Background and aims: Inflammatory bowel disease is a chronic disorder of the gastrointestinal tract. Tacrolimus is a calcineurin inhibitor used in the prophylaxis of rejection after a solid organ transplant. There is some evidence for its use in inflammatory bowel disease, although there is a lack of information about the patients who will benefit the most with this drug and the prognostic factors for a favorable response.

Material and Methods: We performed a multicentric retrospective study evaluating all the patients who have received tacrolimus in the last 10 years as a treatment for IBD in our area.

Results: A total of 20 patients, 12 with Crohn's disease and 8 with ulcerative colitis, were included in four hospitals. The two most common indications were steroid-dependency and fistulizing Crohn's disease. The median time receiving tacrolimus was 11 months. In 12 patients the treatment was stopped. The main reasons for drug withdrawal were absence or loss of response. The median clinical follow-up was 35.5 months. Overall, a 25% achieved clinical remission and 40% were in partial response. Biologic-naïve patients demonstrated a significantly better remission rate as compared with those that were not (80 vs. 7%). Patients who achieved remission were more likely to have a significant reduction in C-reactive protein values 1 month after starting the drug. Seven patients required surgery during the follow- up period.

Conclusions: Patients naïve to biologics showed a significantly better response to tacrolimus. A reduction in C-reactive protein one month after starting this drug was associated with clinical remission.

Key words: Anti-TNF. Biological drug. C-Reactive protein. Inflammatory bowel disease. Tacrolimus.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) are two chronic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. Both are included in the term inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Their treatment usually involves the use of immunosuppressive therapy in order to control the inflammatory process in the gut. The most frequently used treatments include thiopurines, methotrexate, and biologic drugs. Despite these therapeutic options, up to 15% of patients with UC and more than half with CD require surgery during follow-up. In the remaining cases there may be no response to treatment (primary or secondary non-responders), intolerance to the drug, or the presence of adverse effects from the treatment. This highlights that we still need to find alternative therapies in patients for whom medical treatment options are limited.

Tacrolimus is a calcineurin inhibitor that acts by inhibiting IL-2 production and T-cell activation. In Spain, it is indicated for prophylaxis of rejection after liver, kidney and cardiac transplantation. Nevertheless, there is an increasing evidence for its use in IBD. Two clinical trials have demonstrated its efficacy for inducing remission in moderate to severe UC (1,2). Moreover, multiple observational studies have demonstrated the short- and medium-term efficacy of tacrolimus in both UC and CD in clinical practice.

Despite the recent advances in the medical treatment of IBD, there is a significant number of patients requiring surgery. This is especially relevant in this context because of the important implications of this chronic disease in young people. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy and factors associated with the response to tacrolimus in four hospital units specialized in the care of IBD patients.

Material and Methods

We performed a multi-centric retrospective study in four IBD units in four tertiary hospitals in Spain, namely, the Hospital de Galdakao (five patients), Hospital Universitario de Cruces (nine patients), Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra (seven patients) and Hospital Universitario de Basurto (one patient). Inclusion criteria included an established diagnosis of IBD and an indication of tacrolimus for this disorder. The primary aim of our study was to evaluate the efficacy and the influence of previous treatments, along with the presence of clinical or biochemical factors that predict the response to tacrolimus. All variables were set before the beginning of the study. All the data were anonymously compiled and codified in an electronic database. The Research Ethics Committee of Euskadi approved the final study protocol.

The variables included in the study assessed basic demographic characteristics related to the disease (age at diagnosis, type, extension as defined by the Montreal classification, previous treatment, or surgery). The remaining clinical variables were defined to evaluate the treatment with tacrolimus (indication, medium blood drug levels, concomitant medication, duration of treatment, adverse events, and surgery during follow-up). C-reactive protein (CRP) was used as the main analytical variable at four time points (baseline and one, three and six months after starting tacrolimus). The clinical response to the drug was evaluated globally by the gastroenterologist in charge of each patient with the physician's global assessment (PGA) as remission, partial response, or no response.

Statistical Analysis

First, the descriptive statistics of the demographic, clinical and treatment characteristics of the recruited sample were initially computed: frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables and mean and standard deviations for continuous exposure factors (e.g., age, Harvey-Bradshaw index). Disease, treatment duration, follow-up time and CRP values measured at different points of the study were expressed by means of medians with their corresponding interquartile range. Second, the relationship of the demographic, clinical, and treatment features with the previous anti-TNF exposure was evaluated. The non-parametric Wilcoxon test for independent samples was used when the exposure to factors was continuous, whereas the Chi-squared test (or the Fisher's exact test when needed) was applied when the variable was categorical. Third, the association between the CRP values and the treatment response was also gauged. To this end, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis method (response in three categories) and the Wilcoxon's test (response as dichotomous) were applied. These Methods were also performed when the mean difference in CRP change (difference of the CRP values between the baseline and each measure) values for each response status were compared. All the statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Figures were depicted using R 3.2.2 release. A p-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

A total of 20 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are shown in table I.

Treatment characteristics

Tacrolimus was started between February 2005 and February 2015. All patients started receiving oral tacrolimus (0.1-0.2 mg/kg). The dose was later adjusted by monitoring the blood drug levels. The indications for its use are summarized in table II. The two most common indications were steroid dependency and fistulizing CD, accounting for 85% of cases. All patients have previously been exposed to thiopurines. In 15 cases they had also received biologics, with 10 patients exposed to two or more drugs. Among those previously exposed, 12 patients had received infliximab treatment, 12 adalimumab, 4 certolizumab and 2 ustekinumab. Disease duration was significantly longer in patients previously exposed to biologics (34 vs. 114 months, p = 0.029). In addition, seven patients were treated with leukacytapheresis.

A detailed description of the treatment characteristics can be found in table II. The drug was maintained for a median duration of 11 months (IQR 5-22). Ten patients received the drug for at least 12 months. The clinical follow-up for the whole cohort was 35.5 months (IQR 14-66). Blood drug levels were maintained mostly between 5-10 ng/mL (60% of patients), and between 10-15 ng/ml in 20%. In nine patients (45%), tacrolimus was prescribed as monotherapy. Eleven patients (55%) were concomitantly receiving another drug at some time point: four, immunomodulators (two azathioprine and two methotrexate); eight, biologics (two infliximab, four adalimumab, two ustekinumab), and one, leukocytoapheresis.

The treatment was terminated during follow-up in 12 patients (60%). The reason for drug withdrawal was the absence of response in five cases, loss of response in five cases, and adverse effects in three cases. The adverse events that led to the discontinuation of the drug were: an increase in serum creatinine levels (maximum creatinine levels < 1.5 mg/dL), gastrointestinal intolerance, and malaise. Two of these patients were partial responders and one did not show response to tacrolimus.

Overall response rate

Overall, 25% of patients achieved clinical remission and 40% were partial responders. Only 35% did not respond to the drug. Clinical remission was seen in 16% and 37% of cases of CD and UC, respectively. A partial clinical response was observed in 58% and 12%, respectively. Overall response rate was 74% and 49% for CD and UC, respectively. Blood drug levels did not influence the response to treatment. In fact, no patient with high tacrolimus blood levels (10-15 ng/ml) achieved remission. All patients in the high drug blood level group had received biologics previously. The association of tacrolimus and a biologic showed lower remission rates when compared with those on tacrolimus monotherapy (0% vs. 42%, respectively; p = 0.6). Although it was not statistically different, we observed a clear difference between the groups favoring tacrolimus monotherapy. No other treatment received concomitantly with the calcineurin inhibitor showed a significantly different response rate.

There were five patients in whom tacrolimus was indicated because of perianal disease. In this subgroup, we found a partial clinical response rate of 80%. The remaining 20% did not respond to therapy. Although there was a trend towards a better response in patients receiving tacrolimus, this difference was not statistically significant, possibly limited by the small number of patients with this indication.

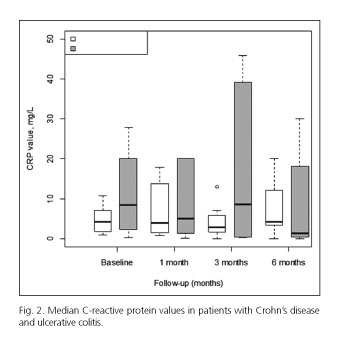

We assessed the CRP levels at baseline and at three pre-established time points during the treatment (one, three, and six months after starting the drug). The median CRP levels and the changes from baseline are detailed in table III. Those patients who achieved remission were more likely to have a significant reduction in CRP values one month after starting the drug (-4.9 ± 3.4, -2.3 ± 3.5 and +19.9 ± 29.1 for remission, partial response and non-response respectively, p = 0.015). Due to the small number of patients in our cohort, we also analyzed the data in two groups comparing those who achieved remission and those who did not (this group included partial responders and non-responders). The findings observed at one month were maintained in this second analysis with statistically significant differences (p = 0.038), but not at three or six months of follow-up. At three months, the mean CRP levels were significantly increased in partial responders, but the Results obtained were different when we compared the data in two groups (remission vs. no remission). These findings are summarized in figure 1 and table III. Furthermore, we explored the differences in CRP between UC and CD patients. In this analysis, there were no significant differences in CRP levels at any of the pre-established time points (Fig. 2). A high inter-individual variability was observed, so these findings should be evaluated with caution.

Response according to previous treatment

Those patients who previously failed biologic therapy showed a worse prognosis. Response to tacrolimus was different in this subgroup. Patients naïve to biologics demonstrated a significantly better remission rate compared with those who were not (80% vs. 7%, p = 0.0038). Only one patient with previous exposure to biologics achieved remission. All partial responders had received biologics before tracolimus. Furthermore, patients who had previously received biologics maintained tacrolimus treatment for a significantly shorter period of time: six months (4-14) vs. 21 months (18-23), p = 0.031. Moreover, patients receiving a combination of tacrolimus and a biologic showed a lower response rate, compared to those on tacrolimus monotherapy (0% vs. 42%, respectively; p = 0.6).

Surgery

Seven patients required surgery during the follow-up period. Five suffered from UC and underwent proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. UC extension was confined to the rectum in one subject, was left-sided in another one, and was extensive in three other subjects. Two patients had CD, both with concomitant perianal disease. One patient underwent total colectomy and the other received a subtotal colectomy with terminal ileostomy due to refractory perianal disease. All subjects were previously exposed to biologics (six received infliximab, four adalimumab, and two certolizumab). Four patients had been treated before with one biologic, one with two drugs and two with three drugs. Tacrolimus was administered for five months (IQR 4-12) before surgery. Only one patient achieved clinical remission but relapsed during treatment. Two were partial responders and four did not show clinical improvement. Two of them also suffered an adverse event that led to drug treatment discontinuation (gastrointestinal intolerance and malaise). Surgery was performed 13 months (IQR 5-24) after starting tacrolimus treatment.

Adverse events

A total of seven patients (35%) suffered adverse events related to the drug. The medical charts showed the occurrence of acute kidney injury (two), gastrointestinal intolerance (one), headache (one), tremor (one), malaise (one), and cramps (one). Drug blood levels were not associated with the development of these adverse events (three events occurring in the group with higher drug blood levels and four in the subgroup with lower drug blood levels). In three subjects (15%), tacrolimus treatment had to be terminated due to clinically relevant events (acute kidney injury, gastrointestinal intolerance, and malaise). Two subjects (one suffering from cramps and one with acute kidney injury) improved after reducing the dose. Both cases of acute kidney injury presented only a mild impairment in renal function (maximum creatinine levels < 1.5 mg/dL) and resolved completely after discontinuing or reducing the dose of tacrolimus. Two patients did not require a specific treatment for the adverse event (tremor and headache). All patients recovered completely and there were no long-term complications related to the treatment.

Discussion

In this clinical-practice study, we have assessed the use of tacrolimus in refractory IBD patients, and demonstrated that its use is associated with a relatively good response rate. Tacrolimus is a calcineurin inhibitor currently approved in Spain for the prevention and treatment of rejection after liver, kidney, or cardiac transplantation (AEMPS, Spanish Agency of Medicines and Sanitary Products). Two randomized, double-blind clinical trials demonstrated the effectiveness of this drug in inducing the remission of steroid-refractory moderate to severe UC (1,2). The first trial by Ogata et al. also explored the optimal drug blood levels, finding a significantly greater clinical response in the group with higher drug blood levels (10-15 ng/mL) (1). In addition, this study included a 10-week open-label phase, in which clinical remission was observed in 29% of patients and mucosal healing in 73%, without patients requiring colectomy. We can obtain more evidence, almost all from retrospective studies, demonstrating relatively good efficacy rates in UC and CD. In UC, retrospective studies have reported remission rates between 9.3-80%, which reflects the high variability between the study population, route of administration, mean drug blood levels and the criteria for evaluating response (3-15). Remission rates demonstrated a similar variability ranging from 9.4-75% in clinical trials and prospective studies (1,2,16-19). In CD, retrospective studies have described remission rates of 6.6-63% (3,4,14,20,21). Just one prospective study has reported a 69% remission rate in CD (22). The European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) guidelines consider that tacrolimus may be effective in perianal CD, but it does not recommend its routine use for luminal Crohn's disease (23,24). The ECCO statements in the management of UC consider tacrolimus as a possible rescue therapy in acute severe flares and also in outpatients with moderately active steroid-refractory UC (25). In Spain, the GETECCU (Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa) guidelines also consider the possible use of this drug in steroid-refractory moderate to severe flares of UC (26).

Our cohort showed a 37% and 16% remission rate in UC and CD, respectively. Moreover, a higher proportion of patients with CD showed some degree of response to tacrolimus (74% for CD and 49% for UC). Therefore our Results show an overall better response rate to tacrolimus in CD. These Results should be evaluated considering that 62% of UC and 83% of CD patients were previously exposed to biologics. Thus, we can speculate that the potential efficacy of tacrolimus could be underestimated in our cohort, especially in CD. In the light of these Results, we consider that tacrolimus shows a relatively good clinical efficacy in this cohort.

These findings should be evaluated with caution, as we are assessing remission rates in a refractory population. Another factor that could have influenced our Results is the presence of lower than expected tacrolimus blood levels, as the optimal drug blood levels have been reported to be 10-15 ng/mL (1). Most of our patients were within the lower range (5-10 ng/mL). Nevertheless, no patient with high drug blood levels achieved remission. Some methodological limitations should also be considered in our study. First of all, its retrospective design may have limited a more detailed evaluation of the clinical efficacy of the drug. Adverse events may have been underestimated, but this effect will be less pronounced in those events clinically significant or requiring drug withdrawal. Another important factor is the small number of patients included and the relative small proportion of patients without previous exposure to biologics. Nevertheless, the difference in remission rates in both groups seems clinically relevant (80 vs. 7%, p = 0.0038). We have included all consecutive patients treated in the last 10 years in four units specialized in the management of IBD, making these Results more consistent. However, our findings should be confirmed in future studies.

Most of the available evidence has been described in refractory patients not responding to conventional management. Studies do not show compelling evidence of the influence of previous drug exposure on tacrolimus response. We observed a significantly better remission rate in those patients naïve to biologics. In addition, all patients previously exposed to biologics showed a partial response to tacrolimus. Furthermore, these patients received tacrolimus for a shorter period of time, reflecting a worse response to the drug. In addition, all cases that required surgery were previously exposed to biologics. Another consideration is that concomitant biologic use showed a trend towards a lower remission rate but this difference was not statistically significant (0% vs. 42%, p = 0.6). Further multivariate analyses were not performed due to the small sample size, but these findings could lead to further studies with this drug. Based on the relatively good response rates in this refractory population, tacrolimus could be an alternative drug in earlier stages of the disease.

There are few reports on the availability of clinical and biological markers of the response to tacrolimus. A recent Australian study found two predictors of surgery in patients receiving tacrolimus: steroids at baseline and the clinical response at 30 and 90 days. Therefore, these authors proposed treating not steroid-refractory patients with tacrolimus and evaluating their response at three months before surgery (14). In our study we have shown that a decrease in CRP levels during the first month of therapy was significantly associated with higher remission rates. Moreover, there were no significant differences in CRP levels between UC and CD patients at any time point. Taking these Results together, we demonstrate that patients starting tacrolimus show early biochemical markers of response, but a clinical improvement may appear during the first three months of therapy. Thus, the changes in CRP during the first month may give valuable information of further probability of the response to tacrolimus. These findings are in line with the evaluation of response to other drugs used in IBD.

In clinical practice, tacrolimus has shown to be effective in IBD, although most of the evidence comes from a refractory population. Our data suggest that these Results could be improved if tacrolimus treatment is considered earlier than it is usually prescribed today, but it may be limited by its safety profile. We also demonstrate the usefulness of early evaluation of CRP changes in predicting the response to tacrolimus in this setting. These Results highlight two potentially valuable clinical and biochemical prognostic markers that could help to evaluate such treatment in clinical practice and guide further studies with tacrolimus for IBD.

Author Contributions

IR-L and JLC conceived the study design, wrote the study protocol and drafted the final manuscript. IR-L, OM, ON, CM and JLC managed the patients and compiled the information. UA performed the Statistical Analysis. JLC critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to and accepted the final version of this manuscript.

References

1. Ogata H, Matsui T, Nakamura M, et al. A randomised dose finding study of oral tacrolimus (FK506) therapy in refractory ulcerative colitis. Gut 2006;55:1255-62. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2005.081794. [ Links ]

2. Ogata H, Kato J, Hirai F, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral tacrolimus (FK506) in the management of hospitalized patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:803-8. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.21853. [ Links ]

3. Baumgart DC, Pintoffl JP, Sturm A, et al. Tacrolimus is safe and effective in patients with severe steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent inflammatory bowel disease-A long-term follow-up. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1048-56. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00524.x. [ Links ]

4. Benson A, Barrett T, Sparberg M, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus in refractory ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease: A single-center experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:7-12. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.20263. [ Links ]

5. Herrlinger KR, Koc H, Winter S, et al. ABCB1 single-nucleotide polymorphisms determine tacrolimus response in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;89:422-8. DOI: 10.1038/clpt.2010.348. [ Links ]

6. Hirai F, Takatsu N, Yano Y, et al. Impact of CYP3A5 genetic polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics and short-term remission in patients with ulcerative colitis treated with tacrolimus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:60-6. DOI: 10.1111/jgh.12361. [ Links ]

7. Ikeya K, Sugimoto K, Kawasaki S, et al. Tacrolimus for remission induction in ulcerative colitis: Mayo endoscopic subscore 0 and 1 predict long-term prognosis. Dig Liver Dis 2015;47:365-71. DOI: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.01.149. [ Links ]

8. Inoue T, Murano M, Narabayashi K, et al. The efficacy of oral tacrolimus in patients with moderate/severe ulcerative colitis not receiving concomitant corticosteroid therapy. Intern Med 2013;52:15-20. DOI: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.8555. [ Links ]

9. Landy J, Wahed M, Peake ST, et al. Oral tacrolimus as maintenance therapy for refractory ulcerative colitis-An analysis of outcomes in two London tertiary centres. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:e516-21. DOI: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.03.008. [ Links ]

10. Minami N, Yoshino T, Matsuura M, et al. Tacrolimus or infliximab for severe ulcerative colitis: Short-term and long-term data from a retrospective observational study. BMJ Open Gastroenterology 2015;2:e000021. DOI: 10.1136/bmjgast-2014-000021. [ Links ]

11. Mizoshita T, Tanida S, Tsukamoto H, et al. Colon mucosa exhibits loss of ectopic MUC5AC expression in patients with ulcerative colitis treated with oral tacrolimus. ISRN Gastroenterol 2013;2013:304894. DOI: 10.1155/2013/304894. [ Links ]

12. Ng SC, Arebi N, Kamm MA. Medium-term Results of oral tacrolimus treatment in refractory inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:129-34. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.20052. [ Links ]

13. Schmidt KJ, Herrlinger KR, Emmrich J, et al. Short-term efficacy of tacrolimus in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis-Experience in 130 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:129-36. DOI: 10.1111/apt.12118. [ Links ]

14. Thin LW, Murray K, Lawrance IC. Oral tacrolimus for the treatment of refractory inflammatory bowel disease in the biologic era. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:1490-8. DOI: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3 18281f362. [ Links ]

15. Yamamoto S, Nakase H, Mikami S, et al. Long-term effect of tacrolimus therapy in patients with refractory ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;28:589-97. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03764.x. [ Links ]

16. Bousvaros A, Kirschner BS, Werlin SL, et al. Oral tacrolimus treatment of severe colitis in children. J Pediatr 2000;137:794-9. DOI: 10.1067/mpd.2000.1091993. [ Links ]

17. Fellermann K, Ludwig D, Stahl M, et al. Steroid-unresponsive acute attacks of inflammatory bowel disease: immunomodulation by tacrolimus (FK506). Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:1860-6. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.539_g.x. [ Links ]

18. Kawakami K, Inoue T, Murano M, et al. Effects of oral tacrolimus as a rapid induction therapy in ulcerative colitis. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2015;21:1880. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i6.1880. [ Links ]

19. Yamamoto S, Nakase H, Matsuura M, et al. Tacrolimus therapy as an alternative to thiopurines for maintaining remission in patients with refractory ulcerative colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011;45:526-30. DOI: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318209cdc4. [ Links ]

20. Gerich ME, Pardi DS, Bruining DH, et al. Tacrolimus salvage in anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody treatment-refractory Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:1107-11. DOI: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318280b154. [ Links ]

21. Lowry PW, Weaver AL, Tremaine WJ, et al. Combination therapy with oral tacrolimus (FK506) and azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine for treatment-refractory Crohn's disease perianal fistulae. Inflamm Bowel Dis 1999;5:239-45. DOI: 10.1097/00054725-199911000-00001. [ Links ]

22. Ierardi E, Principi M, Francavilla R, et al. Oral tacrolimus long-term therapy in patients with Crohn's disease and steroid resistance. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:371-7. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00938.x. [ Links ]

23. Van Assche G, Dignass A, Panes J, et al. The second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis 2010;4:7-27. DOI: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.12.003. [ Links ]

24. Van Assche G, Dignass A, Reinisch W, et al. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: Special situations. J Crohns Colitis 2010;4:63-101. DOI: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.09.009. [ Links ]

25. Dignass A, Lindsay JO, Sturm A, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 2: current management. J Crohns Colitis 2012;6:991-1030. DOI: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.09.002. [ Links ]

26. Gomollón F, García-López S, Sicilia B, et al. The GETECCU clinical guideline for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: A guideline created using GRADE methodology. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;7-36. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

José Luis Cabriada.

Gastroenterology Department.

Hospital de Galdakao.

Barrio Labeaga, s/n.

48960 Galdakao, Vizcaya. Spain

e-mail: jcabriada@gmail.com

Received: 14-05-2016

Accepted: 02-07-2016