My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.109 n.4 Madrid Apr. 2017

https://dx.doi.org/10.17235/reed.2017.4305/2016

CASE REPORT

Enteral feeding via jejunostomy as a cause of intestinal perforation and necrosis

Nutrición enteral por yeyunostomía como causa de perforación y necrosis intestinal

María Victoria Vieiro-Medina, Elías Rodríguez-Cuéllar, Alfredo Ibarra-Peláez, Dánae Gil-Díez and Felipe de-la-Cruz-Vigo

Department of General Surgery and Digestive Diseases. Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre. Madrid, Spain

ABSTRACT

Background: Jejunostomy for enteral feeding is excellent for patients who cannot manage oral intake, with a low complication rate. A Foley catheter, Ryle tube, Kerh tube or needle-catheter (Jejuno-Cath®) are commonly used. It is a safe procedure but it can lead to severe complications.

Case report: We present two cases: firstly, an 80 year old male who was admitted to the Emergency Room with a bowel perforation secondary to Jejuno-Cath® for enteral feeding after a subtotal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction; and secondly, a 53 year old male who was admitted to the Emergency Room due to gastric perforation developing multiple complications, including bowel necrosis and enteral feeding impaction.

Discussion: We have reviewed the recent literature with regard to this rare complication.

Key words: Intestinal perforation. Jejuno-Cath®. Feeding jejunostomy. Enteral feeding.

RESUMEN

Introducción: la yeyunostomía de alimentación es una excelente manera de nutrir por vía enteral a pacientes que no pueden tolerar dieta oral con una tasa de complicaciones baja. Se utiliza comúnmente una sonda de Foley, tubo de Ryle, de Kerh o catéter con aguja (Jejuno-Cath®).

Caso clínico: presentamos el caso de un paciente varón de 80 años que presentó una perforación intestinal como consecuencia de la nutrición a través de un yeyunocath en el postoperatorio de una gastrectomía subtotal con reconstrucción en Y de Roux, y de otro paciente varón de 53 años con perforación gástrica y múltiples complicaciones postoperatorias, entre ellas, necrosis de un segmento de intestino delgado por impactación de nutrición enteral.

Discusión: revisamos la literatura existente sobre esta rara complicación.

Palabras clave: Perforación intestinal. Yeyunocath. Yeyunostomía de alimentación. Nutrición enteral.

Introduction

Jejunostomy is a safe, cost effective and well established access for enteral feeding (EF) and drug administration in patients who cannot manage oral intake. It is performed when EF is expected to last for long periods of time (1-5). The introduction technique could be surgical, endoscopically guided, o radiologically guided (2,3). A Foley catheter, Ryle tube, Kehr tube, and needle-catheter (Jejuno-Cath®) are usually used for this purpose (1). The Jejuno-Cath® provides nutritional support to the surgical patient, and is routinely used in the supramesocolic compartment, trauma and oncologic procedures, as well as in malnourished patients (2,4).

Case report 1

An 80-year-old hypertensive male was admitted to the Emergency Room with a 1 cm neoplasic perforation in the incisura angularis. A subtotal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction, D1 lymphadenectomy and insertion of a Jejuno-Cath® was performed. The anatomopathological report showed a transmural perforation, active antral atrophic gastritis, extended intestinal metaplasia with low grade dysplasia, and an area of high grade dysplasia-carcinoma in situ (pTisN0).

During the immediate postoperative period, the patient required hemodynamic support with vasoactive amines. After four days of parenteral feeding, enteral feeding via a Jejuno-Cath® was initiated with a good response. On day 14 postoperatively, the patient developed intense abdominal pain, oxygen desaturation and agitation, neutrophilia without leukocytosis and the C-reactive protein (CRP) was 21.40 mg/dl. The CT showed a bowel perforation in the right flank with a large subhepatic abscess (18 x 7.4 x 8 cm) with gas inside (Fig. 1A). An urgent laparotomy was performed, revealing a large, white, dense liquid collection compatible with enteral feeding. Two bowel perforations were found as well: a 3 cm perforation, with the Jejuno-Cath® tube protruding through it, located 30 cm away from its insertion point; and a second one 20 cm away from the previous. After an exhaustive washing of the abdominal cavity, two bowel resections with manual anastomosis were performed. The anatomopathological report of the perforated area showed hemorrhagic necrosis with signs suggestive of ischemia. In the subserosa and peritoneum, there was an intense inflammatory infiltrate with foreign body giant cells. The patient passed away after a week due to respiratory insufficiency associated with trilobar mycotic pneumonia.

Case report 2

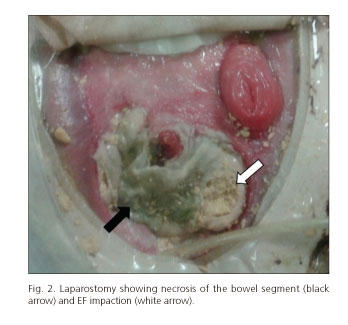

Fifty-three years old male patient with a history of chronic alcoholism who had urgent surgery due to a 5 cm retrogastric perforation at the antropyloric region. It was repaired with a primary suture. Postoperative evolution was torpid, requiring multiple reinterventions. In this scenario the patient developed a catastrophic abdomen with several enteroatmospheric fistulas and laparostomy. This was initially treated using negative pressure therapy (VAC) and placement of a Foley catheter through one of the fistulas holes for EF purposes (previous fistulogram). The patient was in ICU for a long period with multiple complications requiring vasoactive drugs in order to achieve hemodynamic stabilization in the long term, transient renal failure needing hemodialysis filtration, parenteral feeding related hepatopathy, mechanical ventilation-associated pneumonia and septic shock with positive cultures for polymicrobial infection requiring broad-spectrum antibiotics. A month after starting EF via the jejunostomy placed in the fistula hole, a distal obstruction occurred and EF reflow was observed. The laparostomy showed EF impaction in a necrotic bowel segment, causing the obstruction (Fig. 2). Urgent surgery was performed; the necrotic segment was removed, leading to two more fistulas. The anatomopathological report showed transmural ischemic necrosis. The postoperative evolution was fatal, and the patient passed away a few weeks later due to septic shock of abdominal origin.

Discussion

Published complication rates for jejunostomies vary. Complications are most frequent in Roux-en-Y enterostomies (21%), and less frequent in needle inserted catheters (1.5%), with an intermediate rate in the longitudinal Witzel technique, transverse Witzel technique and percutaneous jejunostomy technique (2.1-6.6 and 12%, respectively) (5).

Jejuno-Cath® feeding has multiple complications on record: a) mechanical: accidental withdrawal, catheter obstruction (0.74%), migration to the abdominal cavity, enteroatmospheric fistulas (0.14%), ischemia (0.14%) and intestinal necrosis (0.2%); b) infectious: subcutaneous abscess, abdominal wall infection, pneumonia caused by contamination and aspiration of the enteral feeding; c) gastrointestinal: abdominal distension, colic, diarrhea, constipation, nausea or vomit; and d) metabolic: hypocalcemia (50%), hyperglucemia (29%), hydroelectrolytic and base-acid imbalance, hypoglycemia, hypercalcemia, hypo or hypernatremia, hypophosphatemia and hypomagnesemia (2,4,5). Some complications can be treated without removing the catheter, such as cellulitis and subcutaneous abscess. Other complications such as necrosis, pneumatosis, small bowel obstructions and perforations are rare (4).

Ischemia and subsequent small bowel perforation is one of the most severe complications that may appear (7,8). Even though the ischemia rate is usually less than 1%, rates of up to 3.8% have been published. When this complication appears, an early diagnosis is difficult to achieve. Mortality ranges from 41% to 100% (8,9).

Clinical presentation is very unspecific. The first signs and symptoms include abdominal distention, colic pain and absence of bowel sounds. Subsequent symptoms include paralytic ileus, pneumatosis intestinalis, transmural necrosis and finally septic shock. Findings on abdominal x-rays and CT-scans are: pneumatosis intestinalis (88%), thickened bowel wall (38%), free intraperitoneal fluid and air (38% and 25%, respectively) (10).

The causative mechanism is not clear. Multiple hypotheses have been considered: a) intraluminal factors such as hyperosmolarity, hypertension, bacterial overgrowth, or EF retention and subsequent dehydration (10); b) factors reducing mesenteric blood flow (low cardiac output, insufficient reanimation with fluids, hypotension, atherosclerotic vascular disease or congestive cardiac insufficiency); an inadequate functioning bowel perfusion could lead to bowel ischemia (8-10); c) exogenous factors such as the use of vasoactive drugs (α1-adrenergic stimulation) produce vasoconstriction, reducing even further the mucosa blood flow and contributing to the generation of the ischemia (8).

In the two cases presented, necrosis and bowel perforation were probably caused by multiple factors. Both patients, with recent abdominal surgeries, developed a certain degree of postoperative paralytic ileus, which translates to a higher EF retention time and subsequent dehydration. In the second patient several etiopathogenic factors add up: prolonged stay in the ICU, intestinal fistulas, transient renal failure and subsequent hydroelectrolytic imbalance. Both patients received vasoactive drugs support, therefore, they presented hypotension and/or low cardiac output with tissue hypoperfusion, especially in the splanchnic area. The first patient, with a history of arterial hypertension and advanced age, presented some degree of cardiopathy and peripheral arteriopathy, which could be the cause of the hypoperfusion. In this patient, the catheter and the constant pressure applied by its tip against a single bowel wall point (decubitus) (1) could have played a major role in the perforation since it was found in the final part and not in a distal position. Both patients had multiple risk factors that could have acted synergistically in the etiopathogenesis of the lesion.

Conclusion

Before initiating this type of nutrition, it is advisable to assess the risk factors of bowel necrosis for each patient individually. The two cases presented show the importance of being aware of this possible complication, since a high level of caution is needed to achieve an early diagnosis in order to diminish the high mortality rate.

References

1. Har B, Shinde R, Saha D, et al. Iatrogenic jejunal perforation while FJ tube re-insertion: A rare complication of feeding jejunostomy tube reinsertion. Int J Sci Rep 2015;1(1):92-3. DOI: 10.18203/issn.2454-2156.IntJSciRep20150211. [ Links ]

2. Myers JG, Page CP, Stewart RM, et al. Complications of needle catheter jejunostomy in 2,022 consecutive applications. Am J Surg 1995;170:547-51. DOI: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80013-0. [ Links ]

3. Waitzberg DL, Plopper C, Terra RM. Access routes for nutritional therapy. World J Surg 2000;24:1468-76. DOI: 10.1007/s002680010264. [ Links ]

4. De Gottardi A, Krahenbuhl L, Farhadi J, et al. Clinical experience of feeding through a needle catheter jejunostomy after major abdominal operations. Eur J Surg 1999;165:1055-60. DOI: 10.1080/110241599750007892. [ Links ]

5. Tapia J, Murguia R, García G, et al. Jejunostomy: Techniques, indications, and complications. World J Surg 1999;23:596-602. DOI: 10.1007/PL00012353. [ Links ]

6. Mohamed AA, Fernández OA, Fernández JS, et al. Vías de acceso quirúrgico en nutrición enteral. Cir Esp 2006;79(6):331-41. DOI: 10.1016/S0009-739X(06)70887-9. [ Links ]

7. Sorensen VJ, Rafidi F, Obeid FN. Perforation of the small bowel after insertion of feeding jejunostomy: A case report. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1987;11(2):202-4. DOI: 10.1177/014860718701100221. [ Links ]

8. Spalding DRC, Behranwala KA, Straker P, et al. Non-occlusive small bowel necrosis in association with feeding jejunostomy after elective upper gastrointestinal surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2009;91:477-82. DOI: 10.1308/003588409X432347. [ Links ]

9. Sarap AN, Sarap MD, Childers J. Small bowel necrosis in association with jejunal tube feeding. The surgical patient. JAAPA 2010;23(11). DOI: 10.1097/01720610-201011000-00006. [ Links ]

10. Melis M, Fichera A, Ferguson MK. Bowel necrosis associated with early jejunal tube feeding: A complication of postoperative enteral nutrition. Arch Surg 2006;141(7):701-4. DOI: 10.1001/archsurg.141.7.701. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

María Victoria Vieiro Medina.

Department of General Surgery.

Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre.

Av. de Córdoba, s/n.

28041 Madrid, Spain

e-mail: vickyvieiro@gmail.com

Received: 08-03-2016

Accepted: 20-04-2016

text in

text in