Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO  Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Española de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial

versão On-line ISSN 2173-9161versão impressa ISSN 1130-0558

Rev Esp Cirug Oral y Maxilofac vol.27 no.2 Madrid Mar./Abr. 2005

Caso Clínico

Nasal T/NK cell lymphoma

Linfoma nasal de células T/NK

A. Torre Iturraspe1, S. Llorente Pendás2, J.C. de Vicente Rodríguez3, L.M. Junquera Gutiérrez2,

J.S. López-Arranz Arranz3

|

Abstract:Nasal T-cell and Natural Killer cell lymphoma (NT/NKL), having been given many names, was defined and described in the year 2001 by the World Health Organization (WHO), on the basis of a previous classification by the Revised European-American Lymphoma Classification (REAL) as it is known today. Its incidence in the western world is low, while in Asia it represents the second most frequent group of lymphomas, followed by the gastrointestinal [lymphoma]. It is typically located in the nasal cavity and maxillary sinuses. It is associated with an aggressive clinical course, characterized by the destruction of surrounding tissue. The definitive diagnosis is made by means of in situ hybridization techniques, in order to determine the immunophenotype. Its association with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has frequently been observed. The prognosis of this disease is determined by the International Prognosis Index (IPI) and by the size of the tumor. In spite of being responsive to irradiation therapy, its prognosis is gloomy, and the death of the patient occurs shortly after the diagnosis, generally as a result of treatment complications. Key words: Nasal T/NK cell lymphoma; Epstein-Barr virus; In situ hybridization; Classification; Sinonasal lymphoma. |

Resumen: El linfoma nasal de células T/ natural killer (NK) (LNT/NK), tras haber recibido múltiples denominaciones, ha sido definido y caracterizado en el año 2001 por la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS), basándose en una clasificación previa de la Revised European-American Lymphoma Classification (REAL), de la manera en que se le conoce actualmente. Su incidencia en el mundo occidental es baja, mientras que en Asia supone el segundo grupo de linfomas más frecuente, tras los gastrointestinales. Se localiza preferentemente en las fosas nasales y senos maxilares, mostrando un curso clínico agresivo, definido por una destrucción de los tejidos circundantes. Su diagnóstico definitivo se realiza por medio de técnicas de hibridación in situ, llegando a la determinación de su inmunofenotipo. Se ha observado una frecuente asociación con el virus de Epstein-Barr (VEB). El pronóstico de esta enfermedad viene definido por el índice pronóstico internacional (IPI) y por el volumen alcanzado por el tumor. A pesar de ser radiosensible, su pronóstico es infausto, aconteciendo la muerte del paciente poco tiempo después del diagnóstico, generalmente como consecuencia de las complicaciones del tratamiento. Palabras clave: Linfoma nasal de células T/NK; Virus de Epstein-Barr; Hibridación in situ; Clasificación; Linfoma sinonasal. |

Recibido: 26-04-2004

Aceptado: 18-11-2004

1 Médico Residente.

2 Médico Adjunto.

3 Jefe de Sección.

Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial.

Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias. Oviedo, España.

Correspondencia:

Aintzane Torre Iturraspe.

Fuente del Prado, 11- 2ºA

33009. Oviedo. España

Teléfono: 655 70 75 63

e-mail: aintza_torre@eresmas.com

Introduction

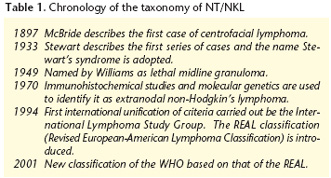

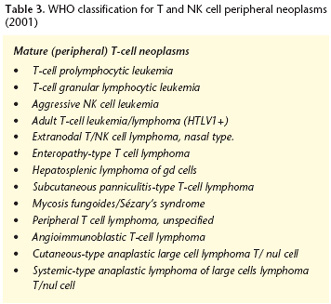

Nasal T/NK cell lymphoma was described by McBride in 1897, although it was not until 1994 that the lesion was accurately identified and classified as an independent entity within the non-Hodgkin's lymphoma group, and named as Nasal T/NK cell lymphoma. During this time it has received many classifications (Tables 1 and 2)1- 3. Its introduction into the WHO classification4,5 has generated conditions favoring international cooperation between oncologists and pathologists. This classification is based principally on the immunohistochemical behavior of tumor cells, and it makes a morphological division along different cellular lines. Within each category the different nosologic entities are grouped together according to clinical presentation and a classification of "real diseases" is therefore offered (Table 3).3,6-11

We present a case of nasal T/NK cell lymphoma, while emphasizing problems that arise when diagnosing this rare entity.

Case Report

A 72-year old female was presented in September 2000 with an ulcerating mucosal lesion in the right palate of the upper jaw. It had been evolving for over a week and was associated with ipsilateral facial discomfort. She had a history of maxillary sinusitis on the right side going back to 1995 that had relapsed. This had required endoscopic surgery on three occasions, with all biopsies being negative for malignancy.

During the examination, an ulcerative lesion of the palate was observed that measured approximately 2 x 2 cm in diameter. It had indistinct borders and a necrotic base associated with erosion of bone surfaces (Fig. 1). The remaining oral, facial and cervical examination was normal. Her general health was not affected nor had she experienced a high temperature. During the radiological examination, orthopantomography and computed tomography (CT) carried out at the same time, only an opacified right maxillary sinus was observed, with no bony erosion that, given the history of the patient, was unremarkable. With regard to the tests performed, there was a significant increase in the globular sedimentation rate (GSR) of 62 mm during the first hour, as well as an increase in Creactive protein (CRP).

The biopsy performed did not provide any specific findings enabling the classification of the lesion, nor could any malignancy be ruled out.

With the results available at the time, a differential diagnosis was given the ulcerative and proliferative lesions located in the cephalic extremity.

In spite of this, and given that the symptoms of pain were increasing, empirical treatment with corticoids was commenced. A small improvement in the symptoms was achieved, but this could not be maintained over time. Two months later there was an increase in both the pain and the ulceration that had spread to the whole of the right half of the maxilla, including the alveolar process and the back of the vestibulum on that side. The CT scan that was carried out at that point revealed the existence of laterocervical adenopathy in the neck with measuring less than 1 cm that were occupying the right maxillary sinus. They had by now destroyed the anterior wall and they were affecting the adjacent soft tissue (Fig. 2). A new biopsy was then taken from the back of the right vestibulum. The result given was of a lymphoproliferative syndrome that was an extranodal type of T/NK non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The presence of EBV by means of classical techniques was not confirmed at the time. Three years later, on revising the anatomopathological samples available of the case, its presence was confirmed by means of in situ hybridization techniques that had not been used at the time of the diagnosis. Other areas of neoplasia in the organism were not visible from scans. Multidisciplinary treatment was introduced with induction chemotherapy (CT) and radiotherapy (RT). The CT was started with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP), but this was suspended during the second cycle as there was a lack of response, and the tumor mass had increased. Radical radiotherapy was then carried out, with the opposite lateral fields technique in order to reach a dose of 45-50 Gy with Co60. The response to the treatment was adverse as the patient died in January 2001 as a result of sepsis due to Pseudomona aeruginosa secondary to the pancytopenia that occurred as a result of the treatment.

Discussion

The incidence of NT/NKL in the west is low and it represents 1.5% of all NHLs. However, in Asia it is the second most frequent group of peripheral lymphomas, immediately after gastrointestinal, representing 2.6 to 7% of the total. These numbers are also observed in some American countries such as Mexico, Guatemala and Peru supporting, according to some authors,12 the theories that exist as to the possible common origin of the inhabitants of these countries with Asians. In the United States an aids-related increase13 in incidence has been observed since 1970. The most common site for NT/NKL is the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, the maxillary being the most frequently involved and the frontal the least.

In practically all the series revised, a higher prevalence in males than in females has been observed, although no consistency can be appreciated in the ratios published due probably to the limited size of the studies. This has varied between 4/1 (male/female) in Europe and 3/1 in Asia7,12,14,15 and up to 1.7/1 in Mexico.24 The most frequently observed age at presentation is in the sixth decade of life, with ranging from the first to the eighth decade.

In the West there is a clear predominance of B-cell lymphomas over T-cell lymphomas in the cervico-facial region, the former representing between 55% and 85% of all sinonasal lymphomas. The origin of this geographic difference is still unclear, although in some geographic areas such as the south of China the incidence of NT/NKL is relatively high, coinciding with areas endemic for EBV infection also associated with a high incidence of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Elevated IgA against EBV viral capside has been observed in these last patients, but not in patients with NT/NKL. In this region B lymphomas are also associated with EBV, which would suggest that factors related with geographical location are of greater relevance than the association of different cellular lines.

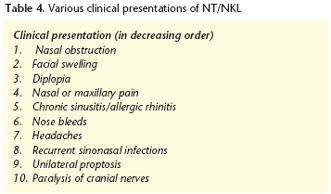

The diagnosis of destructive midface lesions is based on clinical and more especially on histopathological findings, but since this is difficult, at least two biopsies are needed.16 Magnetic resonance (MR) and CT scans are the imaging techniques most used to depict local staging. The images most frequently observed with these techniques are not very clear: the extent of the invasion of the nasal cavity by large masses of soft tissue, and bony erosion of the maxillary sinus walls. The invasion of midface, oropharyngeal, infratemporal and orbital soft tissues indicates an advanced stage (T3, T4). Bony erosion implies behavior that is more aggressive than that observed in the sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma. 17 The typical clinical presentation is characterized by nasal obstruction and facial swelling (Table 4). These tumor lesions are destructive. They may be confined to the nasal cavity or they may affect adjacent structures (nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses, oral cavity). The involvement of lymphatic glands and systemic symptomatology is not very common. In the case we present there was a midfacial destructive lesion, but no systemic involvement, while the imaging and histopathological studies were nonspecific. Nevertheless, a small number of patients can present symptoms in other non-facial areas such as on the skin in other areas of the body, in the lungs and in the gastrointestinal tract. For some investigators,18 this fact suggests that the NT/NKL belongs in reality to a group of lymphomas with identical histological and clinical settings, and that the various sites (lungs, intestine, skin) are different manifestations of the same disease.

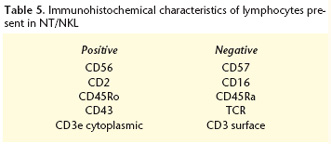

The definitive diagnosis of this entity is histopathological. A characteristic of the initial assessment is for the biopsies not to show any signs of malignancy. This could be due to the limited size of the samples obtained during the biopsies. But the fact is that the biopsy is classified as positive on being repeated during the advanced stages of the disease, when it is giving destructive signs clinically and radiologically. In short, NT/NKL show an aggressive clinical course and an extranodal pattern of progression. Systemic and respiratory complaints are more common in children, and pharyngeal ulcers may also appear.1 The histological imaging of NT/NKL typically shows vascular invasion, necrosis and the presence of inflammatory cells. Although vascular invasion is an inconsistent finding, necrosis is not and it is probably due to the invasion itself of blood vessels or to a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) expression induced by the EBV.5 This is a common factor in other ailments related with this virus such as infectious mononucleosis, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease and lymphomatoide granulomatosis, although in the latter the EBV induces expression in B lymphocytes and not in T-cells. Diagnosis is hampered because of the constant presence of a polymorphic infiltrate of benign inflammatory cells of various sizes, which include neutrophils, atypically small or medium sized histiocytes, and lymphocytes. Table 5 collects the more frequently found immunophenotype.

In situ hybridization techniques are used to determine them, as the techniques traditionally used with monoclonal antibodies have a high percentage of false negatives (Figure 3).4,11,19 By using this technique the presence of the EBV can be demonstrated, even in cases where the tissue sample has a limited number of neoplastic cells. This suggests that it could be used in the future as a diagnostic technique.20 Some investigators10,23 have suggested that NK cells have a monoclonal origin, based on immunohistochemical analysis, with the expression of NK cell markers, such as CD56, and in a high number of cases, absence of the α/ß y γ/δ chains of the Tcell receptors and the CD3 complex. We should remember that NK cells are lymphoid cells that do not have the traditional antigen receptors such as "Tcell receptors" (TCR) or CD3. They have CD16 and CD56 markers and natural cytolytic activity that does not require prior sensitization or the presence of class 1 histocompatibility molecules for carrying out this process. Seki et al.19 concluded, after studying samples analyzed in the south of Japan, that the NT/NKL is made up of a heterogeneous mixture of different cellular types, but that from a immumophenotypic and immunohistochemical status it belongs to NK cellular lines and not T-cell, which supports the monocellular origin of this lymphoproliferative entity in NK cells.

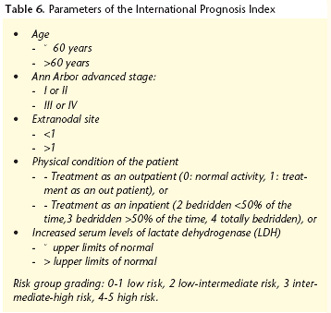

NT/NKL are radiosensitive tumors and local control of the disease is possible, although in the majority of the series published there is a pattern of relapse.21There is unanimous consensus as to the use of combining radiotherapy (RT) with chemotherapy (CT) for advanced stages15,22,23 although during the initial stage, chemotherapy does not appear to lead to an improvement in survival compared with RT on its own. This behavior differs from "non-centrofacial" NHL where joint therapy increases survival.19 Some authors16,24 have observed in prospective studies, that primary CT leads to a high risk of hemorrhage and sepsis complications, and they recommend its use only as coadjuvant therapy. The protocol used most often in CT is CHOP. The combination of second (5-fluorouracil, methotrexate, cytosine arabinoside, cyclophosphamide, vincristine y prednisone o F-MACHOP; cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, etoposide, mechlorethamine, vincristine, prednisone, procarbazine, methotrexate y leucovorin or PROMACE-MOPP) or third generation (methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone y bleomycin or MACOP-B) have not demonstrated being better than the first with regard to complete remission and survival rates. The RT doses achieving the best local control are above 45-50 Gy, independent of the tumor size.23 Another therapeutic possibility is the practice of receiving a bone marrow transplant together with ablative CT, which appears to improve control during a local relapse following failure of conventional treatment with CT. The prognosis factors traditionally used are the histological characteristics and staging upon diagnosis. However, the predictive factor for progression most widely accepted today is the IPI,18,25 which was the result of a project for the development of classification systems for aggressive NHL, which uses clinical criteria reflecting the invasive potential of the tumor (Table 6). There is a simplified model for those under the age of 60, as age is a prognostic factor. Gender, however, does not appear to be associated with survival. Tumor size (which is not however contemplated in the IPI) is considered by some authors23 as an independent prognosis factor for localized aggressive lymphoma.

Most patients die a few months after diagnosis as a result of treatment related complications (RT and CT), common-

References

1. Vidal RW, Devaney K, Ferlito A, Rinaldo A, Carbone A. Sinonasal malignant lymphomas: a distinct clinicopathological category. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1999;108:411-9. [ Links ]

2. Borges A, Fink J, Villablanca P, Eversole R, Lufkin R. Midline destructive lesions of the sinonasal tract: simplified terminology based on histopathologic criteria. Am J Neuroradiol 2000;21:331-6. [ Links ]

3. Jakic-Razumovic J Aurer I. The World Health Organization classification of lymphomas. Croat Med J 2002;43:527-34. [ Links ]

4. Arrowsmith ER, Macon WR, Kinney MC, Stein RS, Goodman SA, Morgan DS y cols. Peripheral T-cell lymphomas: clinical features and prognostic factors of 92 cases defined by the revised European American lymphoma classification. Leuk Lymphoma 2003;44:241-9. [ Links ]

5. Vidal RW, Devaney K, Ferlito A, Rinaldo A, Carbone A. Sinonasal malignant lymphomas: a distinct clinicopathological category. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1999; 108:411-9. [ Links ]

6. Jaffe S E, Chan JKC, Ih-Jen Su, Frizzera G, Mori S, Feller AC y cols. Report of the workshop on nasal and related extranodal angiocentric T/Natural Killer ell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:103-11. [ Links ]

7. Hatta C, Ogasawara H, Okita J, Kubota A, Ishida M, Sakagami M. Non-Hodgkins malignant lymphoma of the sinonasal tract-treatment outcome for 53 patients according to REAL classification. Auris Nasus Larynx 2001;28:55-60. [ Links ]

8. Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, Flandrin G, Muller-Hermelink H, Vardiman J. Lymphoma classification-from controversy to consensus: the R.E.A.L. and WHO Classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Ann Oncol 2000;11:3-10. [ Links ]

9. Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, Flandrin G, Muller-Hermelink HK, Vardiman J, y cols. The World Health Organization classification of neoplasms of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting- Airlie House, Virginia, November, 1997. Hematol J 2000;1:53-66. [ Links ]

10. Noorduyn LA, Torenbeek R, van der Valk P, Snow GB, Balm AJH, Ossenkoppele GJ y cols. Sinonasal non-Hodgkin´s lymphoma and Wegener´s granulomatosis: a clinicopathological study. Vircows Archiv A Pathol Ana 1991;418:235-40. [ Links ]

11. Jaffe ES. Classification of natural killer (NK) cell and NK-Like T-cell malignancies. Blood 1996;87:1207-10. [ Links ]

12. Gaal K, Sun NC, Hernandez AM, Arber DA. Sinonasal NK/T-cell lymphomas in the United States. Am J Surg Patho 2000;24:1511-17. [ Links ]

13. Hanna E, Wanamaker J, Adelstein D, Tubbs R, Lavertu P. Extranodal lymphomas of the head and neck. A 20-year experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;123:1318-23. [ Links ]

14. Cleary KR, Batsakis JG. Sinonasal Lymphomas. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1994; 103:911-14. [ Links ]

15. Cuadra-Garcia I, Proulx GM, Wu CL, Wang CC, Pilch BZ, Harris NL, y cols. Sinonasal lymphoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 58 cases from the Massachusetts General Hospital. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:1356-69. [ Links ]

16. Sobrevilla-Calvo P, Meneses A, Alfaro P, Bares JP, Amador J, Reynoso EE. Radiotherapy compared to chemoterapy as initial treatment of angiocentric centrofacial lymphoma (polymorphic reticulosis). Acta Oncológica 1993;32:69-72. [ Links ]

17. Ooi GC, Chim CS, Liang R, Tsang KWT, Kwong YL. Nasal T-cell/Natural Killer cell lymphoma: CT and MR imaging features of a new clinicopathologic entity. Am J Radiol 2000;174:1141-5. [ Links ]

18. Yang Y, Gau JP, Chang SM, Lin TH, Ho KC, Young JH. Malignant lymphomas of sinonasal region, including cases of polymorphic reticulosis: a retrospective clinicopathologic analysis of 34 cases. Cin Med J (Taipei) 1997;60:236-44. [ Links ]

19. Seki D, Ueno K, Kurono Y, Eizuru Y. Clinicopathological features of Epstein-Barr virus associated nasal T/NK cell lymphomas in southern Japan. Auris Nasus Larynx 2001;28:61-70. [ Links ]

20. Jaffe S E. Nasal and nasal-type T/NK cell lymphoma: a unique form of lymphoma associated with the Epstein-Barr virus. Histopathology 1995;27:581-83. [ Links ]

21. Van Gorp J, de Bruin PC, Sie-Go DMDS, van Heerde P, Ossenkoppele GJ, Rademakers LHP, y cols. Nasal T-cell lymphoma: a clinicopathological and inmunophenotypic analysis of 13 cases. Histopathology 1995;27:139-48. [ Links ]

22. Donato V, Iacari V, Zurlo A, Nappa M, Martelli M, Banelli E, y cols. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy in the treatment of head and neck extranodal non-Hodgkins lymphoma in early stage with a high grade of malignancy. Anticancer Research 1998;18:547-54. [ Links ]

23. Shikama N, Ikeda H, Nakamura S, Oguchi M, Isobe K, Hirota S, y cols. Localized aggressive non-Hodgkins lymphoma of the nasal cavity: a survey by the Japan Lymphoma Radiation Therapy Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001;51:1228-33. [ Links ]

24. Meneses García A, Súchil Bernal L, de la Garza Slazar J, Gómez González E. Linfomas angiocéntricos centrofaciales de células T/NK. Aspectos histopatológicos y algunas consideraciones clínicas de 30 pacientes del Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, México. Cir Ciruj 2002;70: 410-16. [ Links ]

25. The International Non-Hodgkin´s Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. A predictive model for agressive Non-Hodgkin´s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 1993; 329:987-94. [ Links ]

26. Proulx GM, Cuadra-Garcia I, Ferry J, Harris NL, Greco WR, Kaya U, y cols. Lymphoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Treatment and outcome of early-stage disease. Am J Clin Oncol 2003;26:6-11. [ Links ]

27. Prellat J, Sweetenham J, Pickering RM, Brown L, Wilkins B. A singlecentre study of treatment outcomes and survival in 120 patients with peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin´s lymphoma. Ann Hematol 2002;81:267- 72. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em