Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial

versión On-line ISSN 2173-9161versión impresa ISSN 1130-0558

Rev Esp Cirug Oral y Maxilofac vol.29 no.1 Madrid ene./feb. 2007

Cutaneous melanoma of the face with sentinel node in parotid region. Revision of the literature

Melanoma cutáneo facial con gánglio centinela en región parotídea. Revisión de la literatura

R. del Rosario Regalado1, Á. Rollón Mayordomo2, C.I. Salazar Fernández2, D. Moreno Ramírez2, T. Creo Martínez3, J.M. Pérez Sánchez4

1 Médico Residente.

2 Médico Adjunto.

3 Médico Residente.

4 Jefe de Servicio.

Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial. Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena. Sevilla, España.

Dirección para correspondencia

ABSTRACT

Introduction. The parotid gland is the first lymph node echelon in the regional dissemination of frontal, orbital and nasal cutaneous melanomas. Although the lymphoscintigraphy has been become a standard diagnostic technique for studying melanomas, it is not exempt of inconveniences.

Material and methods. We present the case of a patient with frontal melanoma and sentinel nodes in the parotid region, and we discuss the peculiarities, advantages and disadvantages of using this technique in this region.

Conclusions. Although it has been proved that an affected sentinel lymph node is the most important prognostic factor for recurrence and survival, we believe that this is a technique under study, and that its influence on survival should be demonstrated with regard to the alternative of clinical monitoring. It should therefore be indicated in specific cases with greater probabilities of metastases.

Key words: Head and neck melanoma; Lymphoscintigraphy; Neck dissection; Parotidectomy.

RESUMEN

Introducción. La parótida es primer escalón ganglionar en la diseminación regional de los melanomas cutáneos de región frontal, orbitaria y nasal. Aunque la linfografía se ha convertido en una prueba diagnóstica estándar en el estudio del melanoma, no está exenta de inconvenientes.

Material y método. Presentamos el caso de un paciente con melanoma frontal y ganglios centinela parotídeos y discutimos las particularidades, ventajas y desventajas de la técnica en dicha región.

Conclusiones. Aunque se ha demostrado que la afectación del ganglio centinela es el factor predictor más importante de recurrencia y supervivencia, creemos que es una técnica en estudio cuyo efecto en la supervivencia debe ser demostrado frente a la alternativa de seguimiento clínico y que por tanto debe indicarse en casos seleccionados con mayor probabilidad de metástasis.

Palabras clave: Melanoma de cabeza y cuello; Linfografía; Disección cervical; Parotidectomía.

Introduction

Most cutaneous melanomas of the head and neck are located in the forehead and face1,2

Metastases to regional lymphatic nodes occurs in 14% to 60% of patients depending on stage,3,4 and the parotid region can be affected in 2.4% of cases.5

The introduction of lymphoscintigraphy has permitted locating the first likely draining lymph node of the lesion. This in turn permits, following excision, the early diagnosis of nodal metastasis with relatively simple surgery, little morbidity and even under local anesthesia. If involvement is confirmed, early treatment by means of regional lymphadenectomy can be carried out.6,7

In spite of the advantages that the sentinel node technique represents, there are opinions against its general use and indication.8,9 The parotid region is one of the areas where these controversies are greatest because of the clinical, technical and surgical characteristics of the region.5,10

The case of a patient with melanoma of the frontal region and sentinel node in the parotid gland is presented and the peculiarities, advantages and disadvantages of using this technique in this area are discussed.

Case report

The patient was 24 years old male with no relevant medical history. He was operated by the department of Dermatology in our hospital as a result of a melanoma in the frontal region. The lesion was reported as stage II, superficial spreading malignant melanoma with a Breslow measurement of 2 mm.

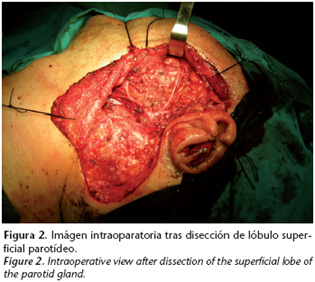

The preoperative lymphography showed two sentinel nodes, a primary one in the center of the left parotid gland, and another secondary one in the tail of the gland. After this finding he was referred to our service for surgical intervention, and a total conservative parotidectomy was carried out together with removal of fatty tissue from the lower axis. The anatomopathologic report of the surgical specimen ruled out the presence of metastasis.

The patient evolved favorably and to date, after a follow- up of 24 months, local, nodal or distant recurrence has not been observed.

Discussion

The incidence of metastasis in parotid lymph nodes of cutaneous melanoma of the facial region, detected by means of a prophylactic parotidectomy is 2.4%,5 and it can reach 8%11 and 13%12 in studies carried out with the sentinel node technique.

Given that the probability of regional metastasis from head and neck melanomas is lower than 20%, and that prophylactic lymphadenectomies do not lead to increased survival,13 the indication for elective node dissection is controversial, and many authors opt for monitoring the patient and treating metastasis when detected. 14

Elective or prophylactic neck dissection entails extra or unnecessary treatment for patients with no lymph node metastasis, which can vary between 95.7 and 87% of cases,5,11,12 and this implies increased morbidity and costs.

This elective treatment in the head and neck region should generally include the parotid region, and it should consist in a prophylactic parotidectomy, with the risks and sequelae that this implies: temporary facial nerve weakness in 15% of patients and permanent branch weakness in under 5%,15 a risk that increases in the marginal branch if accompanied by elective neck dissection, or Freys syndrome to 30% together with the aesthetic sequelae due to indentation or scarring.11,15

Another disputed aspect of head and neck melanoma concerns predicting each patients regional lymphatic drainage path.12,14 While some authors believe that lymphatic metastases to the neck follow a fixed and predictable model,14,16,17 which in 92%18 and 97%19 of patients is identified correctly, for others the distribution pattern is variable. 12,20 However, this prediction only identifies the neck areas that can be affected by dissemination, but not the exact site or the patient with metastasis. This allows more selective prophylactic regional lymphadenectomies to be carried out of the areas that are possibly affected, but without a reduction in number, that is, the number of patients that are overtreated.

The advantage of the lymphoscintigraphy is that the lesions drainage node can be located and, after removal and analysis, those patients with metastases can be identified. This will permit the following: Firstly, knowing the individual lymphatic drainage pattern of each patient. Secondly, the exact stage. Thirdly, it will permit early therapeutic node dissection in a second procedure. Fourthly, the adjuvant complementary therapy indicated can be carried out. And fifthly, it will allow having prognostic information with regard to survival and recurrence. This is a surgical diagnostic technique that is indicated for melanomas with a depth of over 1mm or Clark level IV.21,22 For those patients with a negative sentinel node, the technique avoids aggressive surgery such as elective neck dissection or an elective parotidectomy and therefore, the morbidity and cost.8

However, the sentinel node technique also has disadvantages and the information that it provides is controversial, which means that justifying its use, as opposed to waiting and watching, can be difficult.9

In 34% of patients the lymphography detects nodes that do not correspond with those predicted clinically.10 This discordance consists in identifying as sentinel nodes retroauricular nodes in 13.4% of cases, and contralateral nodes in 72% of cases. These are findings that are contrary to those observed during monitoring, as the incidence of metastases in these nodes varies between 1.5-2.9%.10,18,19

The technique has a rate of false negatives that is less than 4% if concomitant node dissection is carried out.23 However, if the criteria is recurrence in the region of the sentinel node with no previous dissection, the rate of false negatives can vary between 0 and 25% depending on the follow-up period, the anatomopathological study carried out (immunohistochemical or not), the experience of the investigating team and the method used.9,10,12 We believe that some results can be improved by using an intraoperative gamma probe as used by Lin et al.24

Few complications have been described and they include: seroma (3%), infection of the wound (3%), hematoma (2.5%), allergic reaction.24,25 There is also some discussion as to radioactive tracers and coloring materials contributing to increased in-transit metastasis.24,26

Finally, it should be kept in mind that this is an intervention that is purely diagnostic, and there are no data as to its efficiency with regard to survival - that is to say, if prompt treatment of these patients, once metastasis has been detected, improves survival.9

The aspects that have to be taken into account with a sentinel node in the parotid region are the general aspects that have previously been described, and to which we have to add those related to location, as if the sentinel node is close to the facial nerve, excision is more complicated.10,12

The incidence of lymphatic metastasis of the parotid region in early stage melanomas of the head and neck is around 2.4%- 13%,5,11,12 however the detection of preoperative sentinel nodes in this region varies between 95% and 35.2%,10-12 which can be explained by differences in equipment and in the experience of the team.

Sentinel nodes of the parotid region can be classified as intraparotid, those that are situated within the gland, or periparotid, which are situated on the outside or in the peripheral area (these in turn are classified as anterior, infraglandular and supraglandular).11,12 In the series by Ollila et al.12 and Fincher et al.11 the distribution between intraparotid and extraparotid nodes was 50%.

Although some authors question the safety of carrying out a lymphadenectomy of the sentinel node in the parotid region,5,10 Ollila et al.12 carried this out in 37 out of their 39 patients, and Fincher et al.11 in 12 out of their 18 patients (6 with periparotid nodes and 3 with intraparotid nodes), as they considered that intraparotid nodes could be excised with minimal risk.11 They recommend meticulous intraglandular dissection, and that the electric bistoury be used prudently.11,12

Given the risk of permanent damage to the facial nerve, the alternative is carrying out a conservative parotidectomy27 before locating and dissecting the facial nerve, and removing the gland where the node is located, as carried out by Fincher et al.11 in their six remaining patients (33% in total) with intraparotid nodes. This entails carrying out a prophylactic parotidectomy, and the surgery will be more extensive. In addition surgical time and hospital stay will be greater than with a simple adenectomy.

The main inconvenience of an isolated adenectomy is damaging the nerve on excision, or a second surgical procedure if a parotidectomy were necessary. In order to avoid this, Lin et al24 recommend the use of systems for non-invasive intraoperative monitoring. The only complication for Ollila et al.12 in their series of 37 lymphadenectomies of the parotid region, was one case (2.6% of patients) of transitory paresis of the facial nerve, even when an average of 2.3 nodes per patient were excised. Fincher et al,11 in their series of 12 lymphadenectomies of the parotid region, did not encounter any complications, nor did Lin.24

In the parotid, the rate of false negatives was 3.1%- 12.5%.10,12,23 The sensitivity of the technique was 64-80%. In other words, of the patients that had subclinical metastasis in the parotid, 20-36% were not detected (false negatives), 10,12,24 which can be explained by the small size of the nodes.10,11

With the aim of improving results, injecting abundant contrast material should be avoided for melanomas of the cheek, so as to avoid extravasation or the superpositioning of the parotid, and raising fine skin flaps, so as to avoid including any nodes in the flap has also been recommended. 14

Once involvement of the parotid gland has been confirmed, most authors agree that a total conservative parotidectomy should be carried out, and some are in favor of also carrying out neck dissection12,14 as 50% of patients with affected parotid nodes have, or will have, neck metastasis. 12

Most parotid nodes are located in the superficial region of the gland.5,26 According to anatomic studies, in the superficial lobe there may be up to 20 nodes and in the deep lobe there may be 0-5 lobes.28,29 Although it would appear that the superficial parotidectomy is not effective elective treatment, as not all intraglandular nodes are eliminated, if this is carried out and no positive nodes are observed, it should be kept in mind that recurrence in the deep lobe has not been described.5 However, it is not clear if, after a superficial parotidectomy with positive nodes, a deep parotidectomy will have to be carried out later, especially in those cases where a parotidectomy has been carried out as a technique for removing a sentinel node.

Conclusion

Although it has been demonstrated that an affected sentinel node is the most important factor for predicting recurrence and survival,23 we have some doubts as to whether this factor justifies carrying out diagnostic-surgical tests, as opposed to the alternative which would be clinical following. We should perhaps wait for its efficacy with regard to survival to be demonstrated. We believe that it should be indicated selectively and individually as an experimental technique, or used within clinical trials9 as occurs in our hospital.

In cases where this is carried out, and where nodes are detected in the parotid region, the preoperative lymphography should be analyzed in order to distinguish if the node or nodes are periparotid or intraparotid, and in this last case the depth involved should be evaluated.

For superficial periparotid and intraparotid nodes, highresolution ultrasound should be carried out, which will permit confirming the existence and location of adenopathies that measure up to 2.5 mm, and that are confirmed intraoperatively by probe, and adenectomy.

In deep intraparotid nodes, when there is risk of nerve damage, we believe that what should be indicated is a superficial conservative parotidectomy. Confirmation should then be carried out by probe that all nodes have been removed, and that no remains have been left in the deep lobe or level I of the neck.

![]() Dirección para correspondencia:

Dirección para correspondencia:

Ruth del Rosario Regalado

Avda/ Escultora La Roldana nº11 1º A

41500 Alcalá de Guadaíra. Sevilla, España.

E-mail: ruthdelrosario@eresmas.com

Recibido: 02.11.05

Aceptado: 06.10.06

References

1. OBrien CJ, Coates AS, Petersen-Schaefer K, Shannon K, Thompson SF, Milton GW, et al. Experience with 998 cutaneous melanomas of the head and neck over 30 years. Am J Surg 1991;162: 310-4. [ Links ]

2. Kane WJ, Yugueros P, Clay RP, Woods JE. Treatment outcome for 424 primary cases of clinical stage I cutaneous malignant melanoma of head and neck. Head Neck 1997;19:457-65. [ Links ]

3. Myers JN. Value of neck disection in the treatment of patients wiyh intermediate- thickness cutaneous malignant melanoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;125:110-5. [ Links ]

4. Harris C, Bailey J, Blanchaert RH. Surgical management of cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin North Am 2005;17:191- 204. [ Links ]

5. O´Brien CJ, Petersen-Schaefer K, Papadopoulos T, Malka V. Evaluation of 107 therapeutic and elective parotidectomies for cutaneous melanoma. Am J Surg 1994;168:400-3. [ Links ]

6. Morton DL, Wen DR, Wong JM, Economou JS, Cagle LA, Storm FK, y cols. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch surg 1992;127:392-9. [ Links ]

7. Morton DL, Wen DR, Foshag LJ, Essner R, Cochran A. Intraoperative lymphatic mapping and selective cervical lymphadenectomy for early-stage melanomas of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:1751-6. [ Links ]

8. Brobeil A, Cruse CW, Messina JL, Glass LF, Haddad FF, Berman CG, y cols. Cost analysis of sentinel lymph node biopsy as an alternative to elective lymph node dissection in patients with malignant melanoma. Surg Oncol Clin North Am 1999; 8:435-45. [ Links ]

9. Meirion Thomas J, Patocskai EJ. The argument against sentinel node biopsy for malignant melanoma. BMJ 2000;321:3-4. [ Links ]

10. O´Brien CJ, Uren RF, Thompson JF, Howman-Giles RB, Petersen-Schaefer K, Shaw HN, y cols. Prediction of potential metastatic sites in cutaneous head and neck melanoma using lymphoscintigraphy. Am J Surg 1995;170:461-6. [ Links ]

11. Fincher TR, OBrien JC, McCarty TM, Fisher TL, Preskitt JT, Lieberman ZH, y cols. Patters of drainage and recurrence following sentinel lymph node biopsy for cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; 130:844-848. [ Links ]

12. Ollila DW, Foshag LJ, Essner R, Stern SL, Morton DL. Parotid region lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for cutaneous melanoma. Annals of Surgical Oncology 1999;6:150-4. [ Links ]

13. Lens MB, Dawes M, Goodacre T, Newton-Bishop JA. Elective lymph node dissection in patients with melanoma. Arch surg 2002;137:458-61. [ Links ]

14. O´Brien CJ, Shah JP, Balm AJ. Neck dissection and parotidectomy for melanoma. En: Textbook of Melanoma. Ed Thompson JF, Morton DL, Kroon BB. London Libro 2004;296-306. [ Links ]

15. Bron LP, O´Brien CJ. Facial nerve function after parotidectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;123:1091-6. [ Links ]

16. Wells KE, Cruce CW, Daniels S, Berman C, Norman J, Reintgen DS. The use of lymphoscintigrafy in melanoma of the head and neck. Plast Reconstr Surg 1994; 93:757-61. [ Links ]

17. Shah JP, Kraus DH, Dubner S, Sarkar S. Patters of regional lymphatic metastases from cutaneous melanomas of the head and neck. Am J Surg 1991;162:320- 3. [ Links ]

18. Pathak I, OBrien CJ, Petersen-Schaeffer K, McNeil EB, McMahon J, Quinn MJ, y cols. Do nodal metastases from cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck follow a clinically predictable pattern? Head Neck 2001;23:785-790. [ Links ]

19. OBrien CJ, Petersen-Schaefer K, Ruark D, Coates AS, Menzie SJ, Harrison RI, y cols. Radical, modified and selective neck dissection for cutaneous malignant melanoma. Head Neck 1995;17:232-41. [ Links ]

20. Norman J, Cruse CW, Espinosa C, Cox C, Berman C, Clark R, y cols. Redefinition of lymphatic drainage with the use of lymphoscintigraphy for cutaneous melanoma. Am J Surg 1991;162:432-7. [ Links ]

21. Balch CM, Mihm MC. Reply to the article "The AJCC staging proposal for cutaneous melanoma: comments by the EORTC Melanoma Group" by DJ Ruiter y cols. (Ann Oncol 2001;12:9-11). Ann Oncol 2002;13:175-6. [ Links ]

22. Morris KT, Stevens JS, Pommier RF, Fletcher WS, Vetto JT. Usefulness of preoperative lymphoscintigraphy for the identification of sentinel lymph nodes in melanoma. Am J surg 2001;181:423-6. [ Links ]

23. Gershenwald JE, Thompson W, Mansfield PF, Lee JE, Colome MI, Tseng C, et al. Multi-institutional melanoma lymphatic mapping experience: the prognostic value of sentinel lymph node status in 612 stage I o II melanoma patients. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:976-83. [ Links ]

24. Lin D, Kashani-Sabet M, Singer MI. Role of the head and neck surgeon in sentinel lymph node biopsy for cutaneous head and neck melanoma. Laryngoscope 2005;115:213-7. [ Links ]

25. Jansen L, Nieweg OE, Peterse JL, Hoefnagel CA, Olmos RA, Kroon BBR. Reliability of sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging melanoma. Br J Surg 2000;87: 484-9. [ Links ]

26. Muller MGS, Van Leeuwen PAM, Pijpers R, Van Diest PJ, Meijer S. Pattern and incidence of first site recurrence following sentinel node procedure in melanoma patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 2000;26:272. [ Links ]

27. Eicher SA, Clayman G, Myers J, Gillenwater A. A prospective study of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for head and neck cutaneous melanoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002;128:241- 6. [ Links ]

28. Barr LC, Skene AI, Fish S, Thomas JM. Superficial parotidectomy in the treatment of cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck. Br J Surg 1994; 81:64-5. [ Links ]

29. McKean ME, Lee K, McGregor IA. The distribution of lymph nodes in and around the parotid gland: an anatomical study. Br J Plast Surg 1985;38:1-5. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en