Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Española de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial

versão On-line ISSN 2173-9161versão impressa ISSN 1130-0558

Rev Esp Cirug Oral y Maxilofac vol.30 no.5 Madrid Set./Out. 2008

Maxillofacial injury by bull goring: literature review and case report

Herida por asta de toro en el área maxilofacial: revisión de la literatura y presentación de un caso

J.L. Crespo Escudero1, J. Arenaz Búa2, R. Luaces Rey2, Á. García-Rozado1, J. Rey Biel4, J.L. López-Cedrún3, J.J. Montalvo Moreno5

1 Médico Adjunto.

2 Médico Residente.

3 Jefe de Servicio.

Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial; Hospital Juan Canalejo. La Coruña. España

4 Médico Residente.

5 Jefe de Servicio.

Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial; Hospital 12 de Octubre. Madrid. España

ABSTRACT

Introduction. Injuries produced by bull goring are relatively common in Spain and South American countries, where bullfights are scheduled regularly. These wounds have specific characteristics that differentiate them from any other type of wounds.

Material and methods. In the summer of 2005, an 18-year-old male patient was brought to the Hospital 12 de Octubre by emergency services after being gored in the cervicofacial region during the running of the bulls in San Sebastián de los Reyes. The patient had an anfractuous, penetrating and blunt wound extending from the left supraclavicular region to the left lip commissure, comminuted fracture of the left mandibular angle and right mandibular body, dentoalveolar fractures of pieces 1.3 to 2.3, and severe laceration of the lingual musculature and mouth floor.

Discussion. Most patients who suffer multiple injuries as a result of bull goring are men, with a mean age of 30 years. Victims usually are spontaneous participants, bullfighting fans rather than professional bullfighters. The wounds produced by the horns of the bull may be located anywhere in the body, but the most frequent location in all the series reviewed was the lower limb. The cervicofacial region is one of less frequently affected regions in all the series. All authors agree that these injuries have a low incidence despite the huge number of bullfight fans and curious spectators who are attracted by bullfight events. Emergency treatment is required because of the particular characteristics of the mechanism of injury. The patient should be taken as rapidly as possible to a hospital. Authors generally agree that any patient who has been gored by a bull must be considered initially, for purposes of management, as a patient with multiple injuries.

Conclusion. Facial injuries caused by bull goring have no equivalent with other etiologies of trauma in the craniofacial region and surgeons must be aware of their distinctive characteristics. The wounds are serious due to the danger of airway obstruction and hemorrhagic shock, but the prognosis is favorable. The successful management and treatment of patients with this type of injury is based on rapid identification of the wounds in order to execute the correct surgical intervention as soon as possible after the accident occurs.

Key words: Bull goring; Facial.

RESUMEN

Introducción. Las heridas por asta de toro son relativamente frecuentes en España y países iberoamericanos, donde los espectáculos con estos animales son habituales. Dichas heridas presentan unas características específicas que las diferencian de cualquier otro tipo de heridas.

Material y método. Se presenta el caso de un paciente varón de 18 años, remitido al Hospital 12 de Octubre por el SAMUR tras sufrir una cornada en la región cérvicofacial durante los encierros de San Sebastián de los Reyes en el verano de 2005. El paciente presenta una herida inciso-contusa y anfractuosa desde la región supraclavicular izquierda hasta la comisura labial ipsilateral, con fractura mandibular conminuta a nivel de ángulo izquierdo y cuerpo derecho, fractura dentoalveolar de piezas 1.3 a 2.3, y laceración severa de la musculatura lingual y suelo de boca.

Discusión. La mayor parte de los politraumatizados por asta de toro son varones, con una edad media de 30. Las victimas suelen ser participantes espontáneos, aficionados a los eventos taurinos y no toreros profesionales.

Si bien las heridas por asta de toro pueden producirse en cualquier parte del cuerpo, la localización más frecuente en todas las series revisadas es el miembro inferior. La región cérvicofacial es una de las menos afectadas en todas las series. Todos los autores coinciden en la baja incidencia de heridas pese a la gran cantidad de aficionados y curiosos atraídos y por esta modalidad de festejos taurinos. Por todas las características particulares del mecanismo de lesión, el tratamiento debe ser urgente y debe realizarse un traslado lo más rápidamente posible a un hospital. Todos los autores están de acuerdo en que inicialmente el paciente con una lesión por asta de toro debe ser considerado un paciente politraumatizado y tratado como tal.

Conclusión. Las heridas faciales por asta de toro son una entidad propia que no tienen equivalente con las distintas etiologías traumáticas de la región craneofacial y cuyas características deben ser conocidas. Aunque son lesiones graves por el peligro de obstrucción de la vía aérea o de shock hemorrágico, su pronóstico es favorable. El éxito en el manejo y tratamiento de los pacientes con este tipo de heridas se fundamenta en una rápida identificación de las lesiones, con el fin de realizar una terapéutica quirúrgica correcta en el menor tiempo posible desde que se produce el accidente.

Palabras clave: Asta de toro; Herida facial.

Introduction

The wounds produced when a person is gored by a bull or other horned animal are a frequent type of injury in Spain and South American countries, where different events related with bullfighting and fighting cattle (e.g., fighting young bulls, play fighting with calves, the running of bulls, bullfights, and other) are common. Other professionals who handle bulls also can suffer goring injuries, such as veterinarians, cattle owners, slaughterers, etc. Given the characteristics of these animals, any patient who has been gored by a bull must be considered as a patient with multiple injuries and treated as such from the first time the patient is seen. In addition, the patient must receive specific treatment for the injured region and organs affected. These wound have special characteristics (muscular tearing, several wound paths, introduction of foreign bodies, discrepancy between the apparent and actual wounds, massive inoculation of germs, and others) that make them singular in terms of their proper examination and treatment. These characteristics differentiate them from other types of penetrating injuries, such as knife and gunshot wounds.4,13

Knowledge of the mechanism of injury of horn injuries is of particular interest for understanding the magnitude of these wounds. When the bull charges, it flexes its neck and then extends it, pressing one or both horns into the body of its opponent. This produces the first upward wound path. The bull continues the movement, raising the victim several centimeters from the ground, while tossing its head with a circular movement. The horn acts as a fixed axis while the circular movement of the bulls head turns the victim on its horn(s), lowering the victims head and raising the feet. This causes new wound paths to open and produces massive tissue damage. After the initial goring, the persons body may shift position and the bull may charge again, goring the person anywhere in the body. At the time of impact, the kinetic energy is transformed into potential energy. The depth of the wound depends on the speed at which the bull was moving at the time of impact and the animals weight. The position of the person being charged also is important (the points of support of the subject determine how much resistance is offered against the force of the horn), as well as the presence of any elements of counterresistance.12 This subjects resistance to the charge, together with the mechanism of injury described, explains why various wound paths and wounds may be present but not identified in the initial examination.1,3,4,7,13

In order to understand the force that a fighting bull can bring to bear when goring a person, it suffices to say that a four-year-old bull weighing four hundred kilograms and in movement develops a force of 470 kilograms that is transmitted to its horns, where a lever mechanism also comes into play.1 García de la Torre describes the general path of bullhorn wounds as triangular in shape. The entry orifice of the wound is the vertex and the base of the triangle is the deepest part of the wound.16,17

Aside from the bulls weight, many other factors intervene in the origin and severity of the injuries, which are listed in Table 1.

It is important to note that the most serious injuries generally occur in people who also have been drinking. According to Monferrer and colleagues,13 alcohol consumption is the most important predisposing factor in goring injuries; it also is associated with a more torpid evolution and more prolonged hospital stay.

The injuries produced by bull goring can be classified into blunt wounds, or contusions, and penetrating, or open, wounds.1,2

1. Contusions are divided into three types:

a. Grade 1: Superficial involvement of the skin and ecchymoses. Depending on the intensity of the trauma, these contusions are divided into a «Focused tip impact» (the contusion produced by the tip of the horn, which consists of a superficial erosion that affects only the skin and subcutaneous cellular tissue) and «Sliding tip impact» (a blunt-force injury that is linear or has several wound paths).

b. Grade 2: Contusions with extravasation of blood into the subcutaneous cellular tissue as the result of the tangential impact of the side of the horn, known as a «Varetazo» or «blow with a horn,» which produces hematoma or Morell-Lavalle exudation.

c. Grade 3: Contusions with superficial or deep tissue necrosis.

2. Open wounds are called «goring wounds» and are traumatic penetrating injuries through the skin and fascias that damage the muscular mass or body cavities. Goring wounds are characterized as being penetrating-blunt wounds with a small entry orifice. There may be several wound paths beneath the tissue surface and major tissue damage.1,2,4,7,8,13

To these injuries must be added the fractures that generally result from the charge of the bull. Burns may occur when the bull has flares or torches attached to its horns.7,13

In addition to the classification based on wound depth, there is another classification created by Ramiro A. Pestana-Tirado, who divides the injuries into three groups according to their severity.15

• Group 1, or mild injuries: wounds that require only «a simple visit to the infirmary» for a medical examination. These wounds do not entail any vital risk to the patient or cause sequelae of any type.

• Group 2, or serious injuries: wounds that require emergency surgery under local or general anesthesia and/or hospitalization, but do not entail any immediate risk to the life of the patient.

• Group 3, or very serious injuries: injuries that threaten the patients life and require emergency surgery under general anesthesia.

Clinical case

We report the case of an 18-year-old man who was sent to Hospital 12 de Octubre by the SAMUR emergency services after being gored by a bull in the left cervicofacial region while running the bulls in San Sebastián de los Reyes in August 2005. The patient was transferred immediately to an operating room after correct orotracheal intubation by the health care personnel of the bullring. The absence of respiratory and cardiovascular abnormalities was confirmed, as well as a stable hemodynamic situation.

Next, under general anesthesia, tracheotomy was performed and the necessary central and peripheral veins were cannulated. The initial and diagnostic examinations were made, which disclosed an anfractuous penetrating-blunt wound from the left upper supraclavicular region to the left labial commissure. A fracture of the right mandibular body, comminuted fracture of the left mandibular angle, dental avulsion of the upper maxillary incisor section, and severe laceration of the lingual musculature and mouth floor were found. The left jugulo-carotid package was exposed and checked for its total integrity. An interdental suture was placed at the level of the fracture foci and adjacent soft tissues to provisionally restore the anatomy. The patient was transferred to the Radiology Department for diagnostic craniofacial CT to rule out the existence of associated central nervous system and cervical injuries. Later, when the patient was in the operating theater, direct laryngoscopy was performed, which demonstrated the absence of laryngoesophageal injuries (Figs. 1, 2 and 3). The entire oral cavity and dependent tissues were carefully washed with a surgical brush and antiseptic solution. Tetanus vaccine and gammaglobulin were administered and systemic intravenous treatment was begun with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and metronidazole.

After correct exposure of the fracture foci at the level of the right mandibular body and left mandibular angle, favored by the wound characteristics, the fracture was reduced and osteosynthesis was performed. Synthes® 2.4 mandibular reconstruction plates were used due to the presence of comminution in one mandible and the high potential for surgical bed infection. The roots remaining in the upper incisor section were extracted and the bone was treated. Sutures were placed and the cervical musculature, mouth floor, and tongue were restored anatomically. The right mental nerve and left lingual nerve were anastomosed microsurgically. The skin and oral mucosa were sutured. The patient remained in the Intensive Care-Multiple Trauma Unit for 36 hours. He presented no neurologic or systemic complications during his stay. After the patient was transferred to the ward, he continued antibiotic treatment for 10 days. His intraoral and skin wounds were cleaned daily with an antiseptic solution. No infection occurred in this territory and the patients evolution was favorable. He was released on the eleventh day.

Discussion

The largest series of bull-goring injuries published to date have been those of Chambres et al.12 (1450 patients), Martínez-Ramos et al.13 (387 patients), Monferrer et al.10(204 patients), Hernández et al.4 (96 patients), and Rudloff et al.9 (68 patients). All these authors agree that most of the multiple injuries caused by goring occur in men with a mean age of 30 years. The age range with the highest frequency of bull horn injuries is between 20 and 30 years. There is a clear predominance of incidence in the months of July, August and September, when bullfighting events are held in most of the towns and cities of Spain. Victims usually are spontaneous participants, people who attend bullfights and other events related with fighting bulls rather than professional bullfighters.13

According to all the series reviewed, the most frequent wound is the goring wound (81% in the study of Monferrer et al.13). Although bull horn wounds can occur anywhere on the body, the most frequent location in all the series reviewed is the lower limb, especially the thigh.1,2,4,10,12,13 Other anatomic regions affected are the abdomen, perineumpelvis, chest, and upper limbs.1-4,10,13 The cervicofacial region is one of the least affected in all the series, except in the study by Chambres and colleagues, in which it was the third most frequent location in 1450 patients (16% versus 64% in the lower limb).13

Chambres et al.12 pointed out a clear and logical direct relation between experience and the incidence of accidents (more experienced people had fewer accidents), but also reported that the highest rates of cervicofacial injuries and of the most serious injuries was in bullfighters. All the authors coincided in pointing out the low incidence of injuries despite the large number of fans of bullfighting and other festivals with fighting bulls.13

Chambres et al.12 reported that wounds of the facial area represent 8% of all wounds caused by bull goring and are divided equally between the facial and cervical regions.

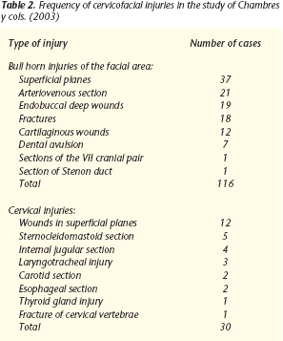

In relation to severity, Chambre et al. affirm that the most frequent injuries are group 2 injuries of the Pestana-Tirado classification (60% in their series), followed by group 3, or very serious, injuries (28%). The group 1, or mild, injuries were the least frequent (12%). However, only 10% of facial injuries are mild, the rest are grade 2 or 3. According to Chambre et al., anfractuous wounds that affect the superficial planes (cutaneous, subcutaneous, or muscular) are the most frequent type of injury in the facial region (37 of 116 cases). The fractures most frequently produced in this type of accident are, in decreasing order, of the mandible, malar, and nasal bones (18 of 116 cases). Other frequent types of injuries of the facial region are vascular injuries (facial and lingual artery), intraoral injuries that affect deep planes, and injuries of the nasal or auricular cartilages. Dental avulsions, facial nerve injuries, and section of the Stenon duct also were observed in their series 12 (Table 2).

In the series of Chambre, 13% of the cervicofacial injuries affected only the neck. All of them were extremely serious: section of the internal jugular (4 cases), section of the internal carotid (2 cases), laryngotracheal injuries, sternocleidomastoid section (5 cases), thyroid gland injury (1 case), and esophageal injuries (2 cases).

Tracheal or laryngeal perforation has been described.12,24 Bull goring wounds usually produce airway opening due to section of the intercartilaginous membranes; the cartilages slip under contact with the horn and rarely fracture. Two zones are especially affected: most frequently, the interthyrohyoid zone with section of the epiglottis, anterior jugular veins and superior laryngeal nerves, followed by the intercricothyroid zone with injury of the recurrent nerves and thyroid lobes.24 The existence of this type of injury should be suspected if air leaks from the cutaneous orifices of the cervical wound or subcutaneous emphysema occurs. This is a constant sign that can appear hours or days after the accident.24 Dyspnea, dysphonia, and hemoptysis also may be present, depending on the magnitude of the injury.12,24

In view of the characteristics discussed above with the mechanisms of injury, treatment must be urgent and the patient should be transferred to a hospital as rapidly as possible. The patient must be assessed immediately in emergency services.13 All authors agree that a patient who has been gored by a bull must be considered initially as a patient with multiple trauma.

Wounds in the facial area rarely require emergency measures other than ensuring airway patency and checking respiratory and cardiovascular function, after which the patient can be transferred to a hospital. However, neck wounds may require immediate attention in the infirmary of the bullring before the patient is transferred to the hospital.12

All authors agree that the general management of these patients must include:

1. In the cervicofacial region, most authors recommend emergency surgical examination of the wound under general anesthesia13,24 and meticulous examination of all possible wound paths of the injury, together with cleaning of the wound paths.12 At the accident site, intubation is the only option for transporting a patient with a cervicofacial wound to a hospital.24 In any case, tracheotomy generally is preferable to intubation because intubation can be extremely complicated in injuries of the facial area (glottis edema deforms anatomic structures with posterior displacement of the epiglottis, laryngeal or tracheal trauma, accumulation of blood in the airway, risk of introducing air or teeth in the airway, etc). Cervical spinal cord injuries may be aggravated by attempted intubation, 18,24 so it will rarely be done at the site of the accident and will be performed when the patient reaches the hospital.24 Once there, the procedure of choice is tracheotomy.

2. Preoperative and postoperative antibiotic therapy and tetanus vaccination: bull horn injuries are very dirty and should be considered contaminated and likely to develop serious infective complications from the time of occurrence. 10 The tetanus vaccination and gammaglobulin administration are imperative and should be given systematically to all patients with this type of wound.1,2,12,14 Horns carry aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, so antibiotic prophylaxis and treatment are a high priority in these patients.1,2,4,8 Martínez-Ramos et al.10 indicate that the antibiotic combination most often used is metronidazole and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, with good results. Other combinations used with good results are metronidazole and tobramycin (or amikacin) or metronidazole with tobramycin (or amikacin) and ampicillin. Chambre also accepts ceftriaxone and metronidazole as a suitable combination. 12 Whatever antibiotic combination is used, it is indispensable that it cover aerobic, gram-negative and gram-positive, and anaerobic microorganisms.

3. Wounds must be cleaned exhaustively with saline solution and an antiseptic solution (hydrogen peroxide and/or povidone-iodine) and all foreign bodies (horn splinters, stones, dirt, remains of clothing, glass, and other) must be removed.

4. Devitalized tissues must be debrided thoroughly, although we should be as economic as possible on skin planes 12 and follow Friedrich in refreshing the margins.

5. Bleeding should be controlled carefully and the area should be reconstructed by planes. If loss of substance occurs, reconstruction should be deferred according to most authors.12

Generally speaking, the complications of bull goring injuries include a high rate of infections (from 9.4% in the study of 96 patients by Hernández et al. to 54.4% in the study of 54 patients by Idikula et al.). Infection is the most frequent complication in all the series studied.1,4

Our patients hospital stay was 7 days. Other series report a mean stay of 5.4 days 1 to 10 days.4,10 Despite the severity of some of these injuries, the mortality rate is considered low in all the series consulted, with a maximum of 4.1%.6 The most frequent causes of death are hypovolemic shock, septic shock, and gaseous gangrene.6,10 The mortality in open neck wounds is 6%, the most frequent cause of death being a vascular wound (40%), followed by airway obstruction and esophageal injuries.24

Conclusions

The facial injuries resulting from bull goring are a distinct entity and are not equivalent to injuries caused by other types of trauma. Surgeons must be aware of the characteristics of these injuries. Although they are serious injuries, due to the danger of airway obstruction or hemorrhagic shock, their prognosis is favorable. The successful management and treatment of patients with this type of injury is based on rapid examination of the wounds in order to perform the correct surgical intervention as soon as possible after the accident occurs.

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr. J.L. Crespo Escudero

Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial

Hospital Juan Canalejo

C/ Xubias de Arriba 84

15006 La Coruña. España

Recibido: 17.07.2007

Aceptado: 21.07.2008

References

1. Mansilla Roselló A, Fuentes Martos R, Astruc Hoffmann A, Flores Arcas A, Albert Vila A, Fernández Valdearenas R, Granda Páez R, Ruiz De Adana Garrido A, López Yébenes A. Estudio de 44 heridas por asta de toro. Cirugía Española 1998;63:36-9. [ Links ]

2. Olsina J. Traumatismos por asta de toro. Med Clin 1975;65:541-542. [ Links ]

3. Fernández M. Cirugía en las heridas por asta de toro. An Real C Nac Med 1984; 101:375-96. [ Links ]

4. Hernández E, Gómez-Perlado B, Villaverde M, Vaquero G, Marugán JA, Besharat F y cols. Heridas por asta de toro. Estudio de 96 pacientes. Cir Esp 1996;59: 156-9. [ Links ]

5. Mateo AM, Larrañaga JR, Vaquero C, Rodríguez-Camarero S, González Fajardo JA, De Marino G. Traumatismos vasculares por asta de toro. Anal Acad Med Cir Vall 1990;28:319-29. [ Links ]

6. Shukla HS, Mittal DK, Naithani YP. Bull Horn Injury: A clinical study. 1977;9:164- 7. [ Links ]

7. Fernández Zúmel M. Cirugía en heridas por asta de toro. An Real Ac Nac Med 1984;28:319-29. [ Links ]

8. Alaústre Vidal A, Rull Lluch M, Caps Ausas I. Infecciones de los tejidos blandos. En: Salvat Lacombe JA, Guardia Massó J (eds). Urgencias Médico Quirúrgicas. Barcelona: Uriach, 1987;289-322. [ Links ]

9. Rudloff U, Gonzalez V, Fernández V, Holguin E, Rubio G, Lomelin J, Dittman M, Barrera. Chirurgica Taurina: a 10-year experience of bullfight injuries. J Trauma 2006;61:970-4. [ Links ]

10. Martinez-Ramos D, Miralles-Tena JM, Escrig-Sos J, Traver-Martinez G, Cisneros-Reig I, Salvador-Sanchis JL. Bull horn wounds in Castellon General Hospital. A study of 387 patients. Cir Esp 2006;80:16-22. [ Links ]

11. Sheldom Lloyd M. Matador versus Taurus: bull gone injury. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2004;86:3-5. [ Links ]

12. Chambres O, Giraud C, Gouffrant JM, Debry C.A detailed examination of injuries to the head and neck caused by bullfighting, and other surgical treatment: the role of the cervico-facial surgeon. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol 2003;124:221-8. [ Links ]

13. Monferrer Guardiola R. Heridas por asta de toro. Aspectos clínico-epidemiológicos de 204 casos asistidos en el Hospital General de Castelló, durante el período 1978-1988. Ciencia Médica 1990;7:262-71. [ Links ]

14. Navarro Roldán J, Castell Campesino L, Escrig Sos J y cols. Heridas por asta de toro, experiencia sobre 31 casos. Ciencia Médica 1990;7:118-24. [ Links ]

15. Pestana-Tirado RA, Ariza Solano GJ, Barrios Air, Oviedo Castaño L. Trauma por cornada de toro. Experiencia en el Hospital Universitario de Cartagena. Trib Med 1997;96:67-83. [ Links ]

16. Rao P, Batí F, Gaudino J y cols. Penetrating injuries of the neck: criteria for exploration. J Trauma 1983;1:47-9. [ Links ]

17. Belinkie S, Russell J, da Silva J, Becker D. Management of penetrating neck injuries. J Trauma 1983;3:235-7. [ Links ]

18. Faucon B, Defrennes D. Urgence devant une plaie cervicale. Encycl Med Chir Urgentes 1994;24:2-20. [ Links ]

19. Navsaria P, Omoshoro-Jones J, Nichol A. An análisis of 32 surgically manager penetrating carotyd artery injuries. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2002;24:349. [ Links ]

20. Moeng S, Boffard K. Penetrating neck injuries. Scand Surg 2002;91:33-40. [ Links ]

21. Faucon B, Deffrennes D. Urgence devant une plaie cervicale. Encycl Med Chir Urgences 1994;24-002-A-20. [ Links ]

22. Giraud C, Gouffrant J. Traumatismes arteriels par cornes de taureau. AERCV. Ed. Actualités de Chirurgie Vasculaire 1995;453-67. [ Links ]

23. Chambres O, Thaveau F, Gabbaï M, Giraud C, Gouffrant JM, Kretz JG. Une discipline atypique: la chirurgie taurine. À propox de deux observations. Ann Chirur 2005;130:340-5. [ Links ]

24. Lahoz Zamarro MT, Valero Ruiz J, Royo López J, Cámara Jiménez F. Traumatismo abierto por asta de toro. Anales ORL Iber-Amer 1990;17:77-84. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em