Introduction

Worldwide, the population is steadily aging, which is leading to an increase in the incidence of chronic diseases. Current changes in the health-care paradigm are generating reforms in the healthcare model in order to provide continuity of care and to integrate health and social care processes and coordination, while ensuring the sustainability of the healthcare system1,2.

The pharmaceutical provision (PP) of nursing homes is a key aspect in improving quality of care and optimizing health resources. Thus, measures related to pharmaceutical care in nursing homes were established by Royal Decree-Law 16/2012 on urgent measures to ensure the sustainability of the Spanish National Health System and improve the quality and safety of its provision3. Specifically, it requires centres with 100 beds or more to establish a hospital pharmacy service (HPS) or, according to official agreements, a medication storage area in the nursing home that is under the management of a designated HPS from the corresponding public network3.

This new legal situation requires the Spanish autonomous regions to restructure their model of pharmaceutical care. Furthermore, several Spanish regional governments have recently included regulations on the PP of nursing homes in their respective pharmaceutical management laws. However, although many Spanish autonomous regions have developed these regulations, great disparities remain between the models developed throughout Spain4,5, and some autonomous regions have yet to adjust their model to the proposed legal framework6.

Law 22/2007 of 18 September on Andalusian Pharmacy7was followed by the publication in January 2016 of Decree 512/2015 of 29 December on the PP of nursing homes in Andalusia8. This Decree regulates the organization of the management of the PP of nursing homes in the Andalusian Public Health Service for residents with the right to such provision. Unlike Royal Decree-Law 16/20123, Decree 512/2015 requires nursing homes with more than 50 beds to have a medication storage area linked to the HPS of a hospital within the Andalusian Health Service in its designated healthcare area.

Decree 512/2015 was first applied in September 2016 as a pilot project conducted in Andalusian public nursing homes under their own management with more than 50 beds and within the jurisdiction of the Department of Senior Citizens8. However, the responsible authorities did not provide instructions on how to implement the PP of the pilot project nursing homes, and thus such provision may have begun in an uneven manner. Therefore, the objective of this study was to provide information on the different established models and to identify the project’s strengths and areas for improvement in the event of it being extended to other centres.

To this end, we analysed the current situation and variability of the PP of the nursing homes included in a pilot project linked to HPSs within the Andalusian Health Service in its designated health care area.

Methods

Cross-sectional multicentre study.

An initial 42-item questionnaire was designed by the study authors to analyse the situation after a 16-month pilot period. The questionnaire was reviewed by two external collaborating experts, taking into account the following criteria:

- Suitability of the questions: whether they were able to obtain the required information.

- Wording: suitability regarding the style, register, and complexity of the sentence used for each item.

- Structure of the questionnaire: suitability of the categorization of the questions and whether they followed a logical order.

In January 2017, the revised questionnaire was sent by e-mail to each of the 12 HPS pharmacists responsible for the nursing homes. In September 2016, these pharmacists had begun to implement the PP of 13 Andalusian public nursing homes under their own management with more than 50 beds within the jurisdiction of the Department of Senior Citizens (two nursing homes were linked to the same HPS with two hospital pharmacists). All questions had to be answered. One month later, those who had not answered were sent a reminder by telephone.

These centres had dependent or non-dependent residents. Dependency was determined according to the degree of autonomy of the residents, using nine variables of the Minimum Basic Data Set, and the amount of care required as measured by nursing time9.

All data were recorded and analysed between March 2018 and April 2018 using Excel 2007. In the descriptive analysis, quantitative variables are expressed as means and standard deviations (SD) or as medians and interquartile ranges (IRC). In the case of asymmetry, qualitative variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages.

Results

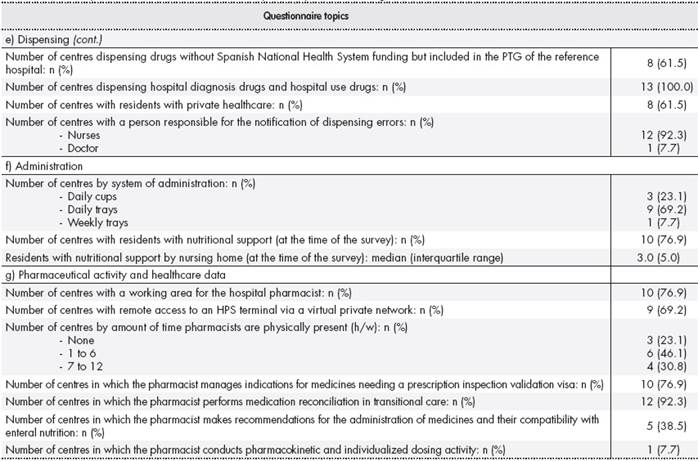

After reviewing the initial 42-item questionnaire, the two experts agreed to exclude six questions due to their lack of relevance to the study. Thus, the final version of the questionnaire comprised 36 questions, which were grouped into seven sections: a) characteristics of the nursing home (5 questions), b) adherence with legislation (3 questions), c) pharmacotherapeutic guide (PTG) and prescription (5 questions), d) preparation and transport (7 questions), e) dispensing (6 questions), f) administration (3 questions), and g) pharmaceutical activity and healthcare data (7 questions). The questions were classified into statistical variables: quantitative (5 questions) and qualitative (31 questions). Qualitative questions were divided into closed Yes/ No questions (20) or closed multiple choice questions (11).

All the pharmacists who started the pilot project answered the questionnaire: 69.2% answered the email, and the remainder replied after they had been contacted by telephone. The HPSs started the PP of nursing homes at different times. Four HPSs started in 2016, six in the first half of 2017, one in July 2017, and the remaining two in October 2017.

The total number of beds available was 1909 with an occupancy rate of 74.9%. Two of the nursing homes had more than 200 beds available, seven had between 100 and 200 beds available, and the remainder had less than 100 beds available. Three centres only had dependent residents, and the remainder had dependent and non-dependent residents. Regarding pharmaceutical care after the implementation of the pilot project, all centres had a medication storage area and stock for emergencies or acute disease. Ten centres had a narcotics log book. All narcotics were kept under lock and key. Nine centres had agreed upon a PTG. Most of the centres had implemented an electronic prescription service (EPS) for all beds. All centres dispensed medicines as individualized unit doses. Three nursing homes did not have a working area available for a pharmacist, and three of the nursing homes did not have a visiting pharmacist. Table 1 shows the results of the questionnaire.

Table 1 (cont.). Responses to the Questionnaire Completed by the 13 Nursing Homes

EPS, electronic prescription service; HPS, hospital pharmacy service; PTG, pharmacotherapeutic guide; SD, standard deviation.

*Management agreement: standardised form describing the steps that the hospital pharmacy service will take according to the provisions of Decree 512/20158and that must be signed by those responsible for managing both the hospital centre and the nursing home.

**Of these, only drugs not included in the pharmacotherapeutic guide but receiving Spanish National Health System funding are dispensed by the Hospital Pharmacy Service.

***Model of pharmaceutical provision of nursing homes prior to Decree 512/20158.

Discussion

This study found variability in the implementation of PP to the pilot project nursing homes, which was a consequence of the lack of guidelines prior to the inception of the project. Differences in the service portfolio of each HPS were another contributing factor. In addition, although Decree 512/20158considered that pharmacists should dedicate around 25 minutes per bed and month, this ratio was not equally fulfilled in all the centres. This disparity may have been due to the different pharmaceutical activities conducted. Another key issue was the uneven involvement of the nursing homes: thus, the visiting hospital pharmacists had to conduct their activity as best they could.

One of the main strengths of the pilot project was that, after its implementation, all centres had a medical storage area with a stock for emergencies or acute disease. A key aspect of specialized pharmaceutical care is the establishment of a pharmacotherapeutic management system based on the evaluation and selection of medicines and nutritional products while taking into account the needs of the patients and the level of care provided by the centres6. Such systems are established by the creation of a Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee in the centre or the incorporation of representatives from the nursing home into the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee of the hospital. More than two-thirds of the pilot centres agreed to establish these systems. The implementation of information systems and the use of commercial EPS applications in 12 of the centres led to medicines being dispensed as individualized unit doses. Both these aspects will contribute to the development of adequate specialized pharmaceutical care that includes patient assessment and continuous and periodic review of the treatments, which are recommended activities according to the published literature6. Another strength of the pilot project was the coverage of treatment needs using hospital diagnostic drugs and hospital use drugs in each centre, thus avoiding hospital referrals. This aspect was incorporated in all the pilot centres. In addition, the pharmacist performs transitional care in most of the nursing homes.

Analysis of the results of the questionnaire identified areas for improvement, such as the need for greater automation in the preparation of individualized treatments in order to reduce medication errors, as suggested in other studies10, and the need for temperature recording devices when transporting thermolabile medications to ensure their proper conservation. The following aspects are essential to increasing the amount of time that pharmacists are physically present in the nursing homes: a working area for the pharmacist (three centres included in the study did not have one); and having available remote access to an HPS terminal through a virtual private network (four centres did not have one). The aim is to increase the pharmacists’ level of integration in the interdisciplinary team and to improve the pharmaceutical care provided. For example, the latter could take the form of making recommendations on the administration of medicines and their compatibility with nutritional support. These types of activity were not implemented in more than 60% of the pilot centres. Pharmacokinetics and individualized dosing activities were conducted in only one of the pilot centres, which may be due to the pharmacist responsible for this activity being different from the person in charge of pharmaceutical care to the nursing homes. This latter aspect is a further improvement to be implemented in centres in which the designated HPS includes this activity in its service portfolio.

To date, no studies have analysed the situation and variability of the PP of nursing homes in a Spanish autonomous region. Some studies have analysed different care models in Spain as a whole. For example, a report published in 2013 analysed the variety of PP from retail pharmacies and specialized pharmacy services in Spain at that time and made proposals for its development from pharmacy services6. In Spain, specialized pharmaceutical care in nursing homes has been mainly developed through two models: the creation of an HPS by each nursing home linked to other nursing homes with or without medication storage areas, or through the HPS of the reference hospital with a medication storage area in the nursing home6. The model implemented in all the pilot nursing homes was based on the creation of medication storage areas linked to an HPS, as established in agreements between the responsible bodies. This approach was similar to that of another study conducted in Spain11, which addressed some aspects similar to those included in our questionnaire. It focussed on specialized pharmaceutical care, such as the development of a PTG system for the management of pharmacotherapy, a weekly medication distribution system (as conducted in all of the pilot centres with dependent residents), the dispensing of hospital use drugs, and the implementation of an EPS in the nursing home.

The present study has some limitations. Firstly, we emphasize that the questionnaire used was not validated. Secondly, the number of nursing homes included in the Decree 512/20158pilot project was low and all of them were from the same Spanish autonomous region; thus, the results cannot be easily generalized. Thirdly, at the time of sending the questionnaire, two HPSs had been providing the service for only three months, which could have been a possible source of variability in the care provided.

A future line of research could analyse differences in implementing PP and their effect on the quality of care provided or health outcomes.

In conclusion, although some inter-centre variability in PP was found, several strengths were identified, the main one being the dispensing of medicines as unit doses in all centres. The main area for improvement was the need to increase the amount of time that pharmacists are physically present in the centres.

text in

text in