Introduction

The last few years have witnessed a growing interest in gaining a greater understanding and coming up with more efficient ways to manage the informed consent (IC) process in subjects participating in clinical trials1,2. The principle of IC is derived from the legal and ethical obligation of investigators to ensure that subjects to a research project freely and voluntarily consent to participating in such a project3.

IC is a lengthy, complex and dynamic process that requires a high degree of engagement, respect and rigor from healthcare providers, investigators and evaluating agencies. Only patients who have received comprehensive information and are capable of understanding the basic aspects of the trial and of giving their consent in an autonomous way should be allowed to participate in a clinical trial4.

The literature on the nature of the IC process is vast and includes numerous guidelines and documents laying out how IC should be managed5-9. Nonetheless, authors have in the most part focused on theoretical aspects, ignoring many of the difficulties that typically arise in clinical practice. In this respect, a series of problems and limitations have been documented, which could affect the quality of the process and even question its validity4. Bureaucratization of IC and its virtual reduction to a legal act, the difficulties arising from patient information sheets, comprehension problems and therapeutic misconception are just some of the difficulties reported in the literatura10-16. As a result, daily practice of IC tends to be far removed from the theoretical ideal and the goals originally proposed.

Spanish IC data tend to be scarce, most of them coming from studies that analyze the IC process from the point of view of ordinary clinical prac tice rather than that of research17,18. However, the very nature of experimental work entails a higher degree of therapeutic uncertainty, which is not always easy to convey or understand.

The purpose of this study is to develop and validate a Spanish-language questionnaire that can be used to analyze the IC process from the point of view of a patient participating in a drug-based clinical trial. More specifically, this article sets out to design a tool that may provide an insight into how the IC process came about, how patients feel about the process and what their level of understanding is about the clinical trial they are asked to participate in.

Methods

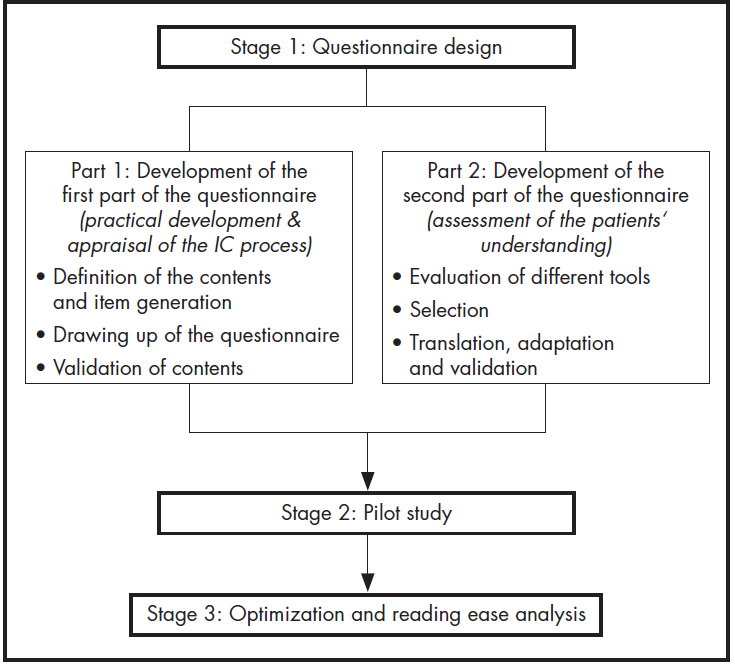

The authors set about developing, adapting and validating a self-administered Spanish-language questionnaire aimed at gaining an accurate understanding of patients’ perception of the IC process. The research was conducted in three stages, following the pattern shown in Figure 1.

Stage 1. Questionnaire design

Part 1. Development of the 1st part of the questionnaire

The first part of the questionnaire was conceived to understand patients’ experience of the IC process, gathering information about the practicalities of the process and about the patients’ subjective perception of it.

The steps followed included:

Definition of the questionnaire contents and wording of the different items. A literature search was carried out for aspects such as the regulation in force concerning research projects19,20, ethical recommendations relative to IC5-7, expert work8,9, and tools available to evaluate the IC process21-23. An analysis was also performed of the references of the articles reviewed so as to identify additional studies. A team of bioethics and research methodology experts used this material to define the domains under which the essential components of the IC process could be grouped and defined the items that were best suited to the purpose of our questionnaire.

Drafting of the questionnaire. Once the items had been selected, they were organized in a logical sequence and the questions were formulated.

Validation of the questionnaire contents. The questionnaire was evaluated by an expert panel made up of members of the La Paz Hospital Drug Research Ethics Committee (CEIm), members of the hospital pharmacy and clinical pharmacology departments, and a research methodology expert. A determination was made of the degree of agreement between experts when evaluating the adequacy, relevance and clarity of each one of the proposed items.

Part 2. Development of the 2nd part of the questionnaire

A second part was added to the questionnaire, intended to evaluate the degree to which patients understood the information given to them during the IC process. To this end, a series of validated English-language tools was selected and subsequently adapted.

The steps followed included:

Tools identification and evaluation.

A literature search was carried out in Pubmed (Medline), IBECS, MEDES and COCHRANE for studies that used standardized tools to evaluate the subjects’ understanding of instructions received. Tools specifically designed for patients with impaired capacity to consent and those for which no validation data were provided were excluded.

The next step was to evaluate the tools’ quality and applicability on the basis of the following criteria: construct, evaluated areas, item generation, evaluation method, administration time, items, scoring and validation.

Tool selection.

The following selection criteria were established: use of objective criteria to measure understanding, adherence to the requirements and the regulations, and implementation feasibility. To qualify for selection, questionnaires had to be amenable to self-administration and should not require answers to be coded.

Translation and adaptation to Spanish.

The translation work was done by a team of a specialist hospital pharmacist, an investigator working in the area of healthcare quality and a linguist, each of them working separately. All three had experience of doing research and were native speakers of Spanish yet bilingual in English and Spanish.

The validity of the contents was evaluated by recourse to the same panel of experts as in part 1.

Stage 2. Pilot study

After bringing together both parts, the full questionnaire was administered to a patient sample in order to evaluate its appropriateness and feasibility in the real world.

The sample included adult patients participating in one of the drug-based clinical trials our hospital is involved in and for which they had been asked to fill in an IC form in the previous 30 days. Patients who could not read or write and those on non-therapeutic or phase IV trials were excluded. The sample size was set at 30 patients as this amount was considered appropriate for an initial exploratory analysis. The pilot study lasted two months, with subjects being selected using convenience sampling. Completion time was duly recoded, and the clarity of the questions and the appropriateness of the format were evaluated by in the course of a personal interview with the patients. Patients’ comments and suggestions were also recorded.

All patients were provided with oral and written information about the project and asked to sign an IC form. The study was approved by the La Paz Hospital’s Drug Research Ethics Committee.

Stage 3. Reading ease: optimization and analysis

The definitive questionnaire was drawn up based on the results of the pilot study. Reading ease was assessed using the Flesch-Szigriszt reading ease score (IFSZ), considered to be a standard for determining the syntactic difficulty of Spanish-language texts24.

IFSZ = 206.835 - 62.3 x (syllables/words - words/sentences)

The Inflesz computer software was used to determine the reading ease of the text based on the ISFZ score. An IFSZ score ≥ 55 indicates acceptable reading ease.

Results

Questionnaire design

First part of the questionnaire

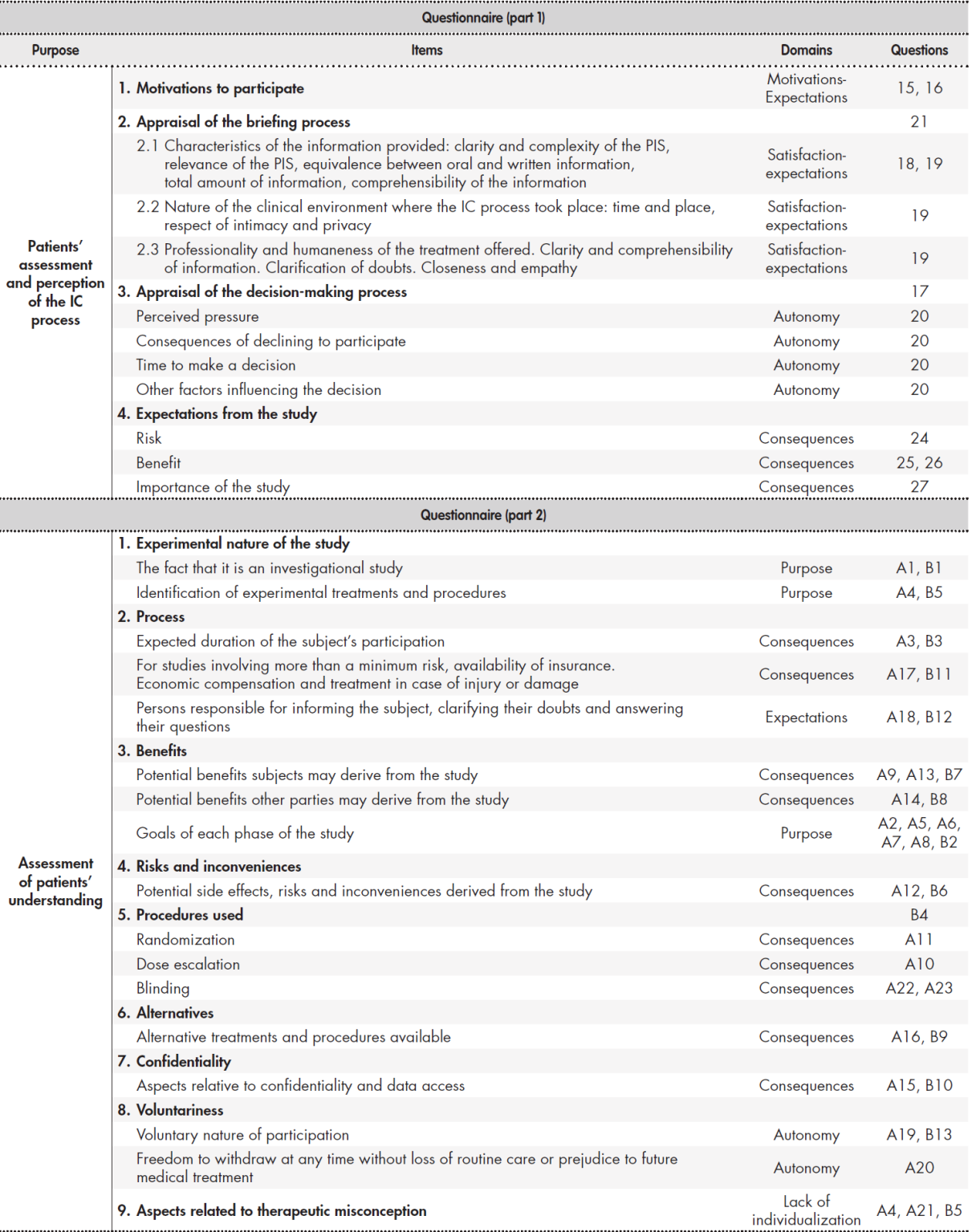

After reviewing and evaluating the information obtained, a group of items was developed related to the practical development of the IC process, together with another group of items related to the patients’ perception of the process. Table 1 shows the domains and the items included in the questionnaire as well as the number of questions under each.

Table 1 was used as a basis to put together 27 closed-ended questions aimed at gaining an understanding of the patients’ perception of the overall IC process. Most questions offered respondents the possibility to choose from a 5-point Likert scale going from “I completely disagree” to “I totally agree”. Some items had to be answered on a Visual Numeric Scale going from 0 to 10. Other types of questions (dichotomous or polytomous) were used in cases where neither of the two scales could be used.

Table 1 (cont.). Questionnaire design: evaluated items and domains

IC: informed consent PIS: patient information sheet.

Given that following the validation process experts reached a level of agreement above 70% for all the items, it was decided to keep them unchanged. Experts nevertheless did decide to remove the intermediate option on the 5-point Likert scale to prevent answers from erring towards the option involving the least commitment. Items related with the patient information sheet were all grouped together.

When asked to review the final version, experts agreed that the questions tackled all the essential aspects of the IC process, that the potential answers were properly categorized, and that the questions were suitably presented.

Second part of the questionnaire

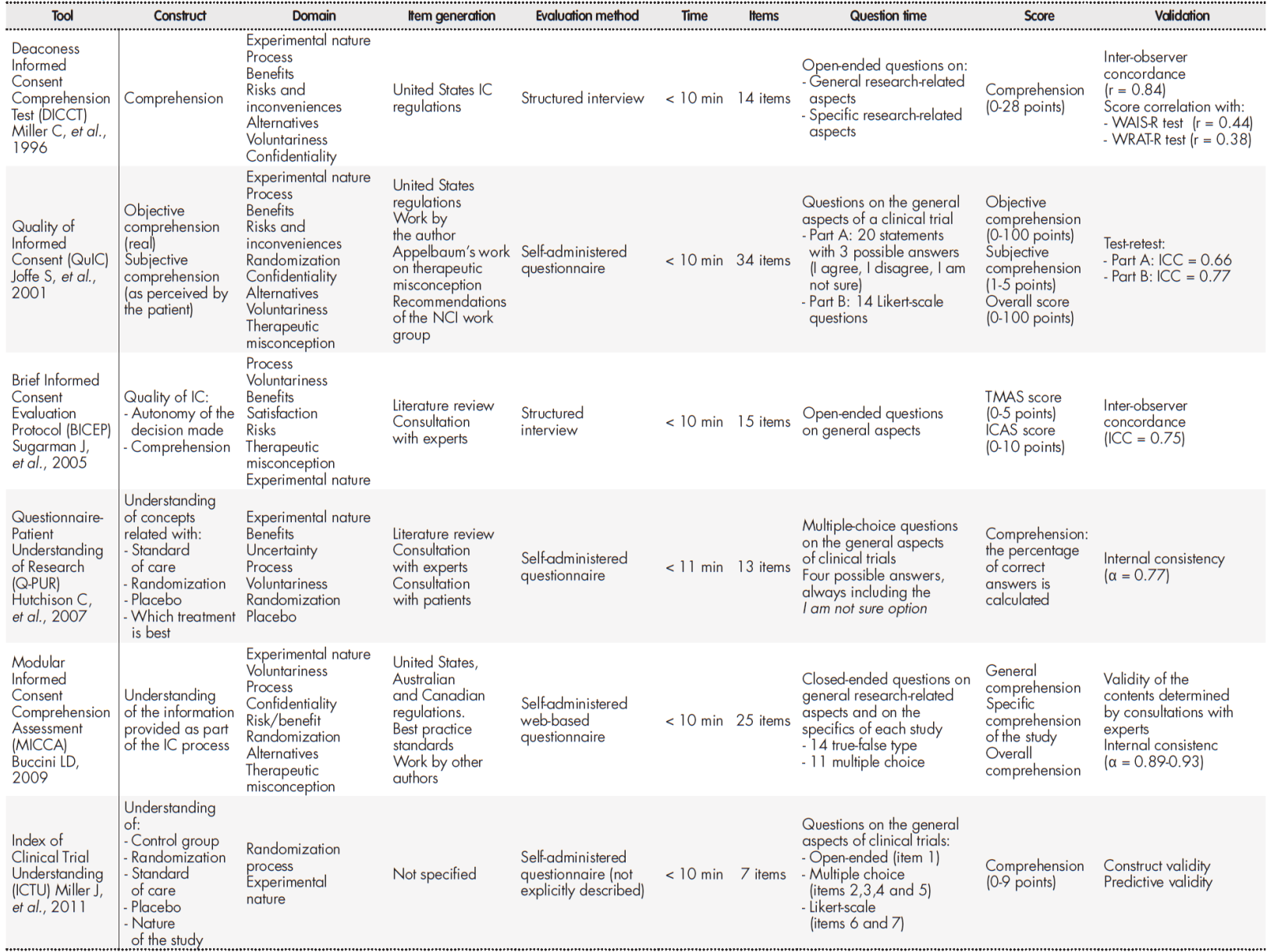

Based on the established criteria, the following instruments were selected to evaluate the subjects’ level understanding: the Deaconess Informed Consent Comprehension Test (DICCT)25, the Quality of Informed Consent questionnaire (QuIC)26, the Brief Informed Consent Evaluation Protocol (BICEP)22, the Index of Clinical Trial Understanding (ICTU)27, the Questionnaire-Patient Understanding of Research (Q-PUR)28, and the Modular Informed Consent Comprehension Assessment (MICCA)29. A comparison of the results obtained is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Comparison of the different tools evaluated

IC: Informed consent; ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient; NCI: National Cancer Institute; WAIS-R: Wechsler Adult Intelligent Scale-revised; WRAT-R: Wide-Range Achievement Test-revised.

After a thorough analysis, S. Joffe et al.’s QuIC questionnaire was selected as it met al.l the predefined criteria. The questionnaire is divided into two sections. Section A seeks to determine the subject’s real (objective) understanding through 20 closed-ended questions with three possible answers each: I agree, I disagree or I don’t know. Section B seeks to determine the patient’s (subjective) understanding of the knowledge through 14 Likert-type questions where they are asked to state their perceived understanding of the different aspects of the study. Response options range from 1 (“I understood nothing”) to 5 (“I fully understood”).

In section A, 100 points were assigned for each correct response, 0 points for each incorrect response and 50 points if the response was I am not sure. The overall score was calculated by estimating the average score. In section B a calculation was made of the mean scores of the 14 questions included. The resulting mean score (range: 1-5) was transformed into a 0-100 score. For both sections it was considered that the higher the score, the higher the level of understanding.

The Spanish translation tried to preserve the semantic and conceptual equivalence of the English version, as well as its original structure. As hardly any discrepancies were found between the versions prepared by each translator, it was decided to combine all translations into one single document.

After evaluating the Spanish version for sufficiency, clarity, coherence and relevance, the experts concluded that the questionnaire allowed an evaluation of the essential aspects of a study which, according to the GCP principles and the existing regulations, must be disclosed to any patient participating in a clinical trial.

A decision was made to include four additional questions to determine the patients’ understanding of aspects related to blinding and therapeutic misconception (questions 21, 22, 23 of section A). The responses to these questions were considered separately when analyzing the results.

Table 1 shows the items included and the IC domains evaluated in the second part of the questionnaire.

Pilot study

The study comprised 32 patients, 50% of whom were male (n = 16) with a mean age of 59.2 years (± 17.3). Of them, 19 (59.4%) were participating in phase III clinical trials, 12 (37.5%) in phase II trials, and 1 (3.1%) in a phase I trial. The most widely represented medical specialties were oncology (9 patients; 28.1%), rheumatology (8 patients; 25%), internal medicine (6 patients; 18.8%) and GI (5 patients; 15.6%).

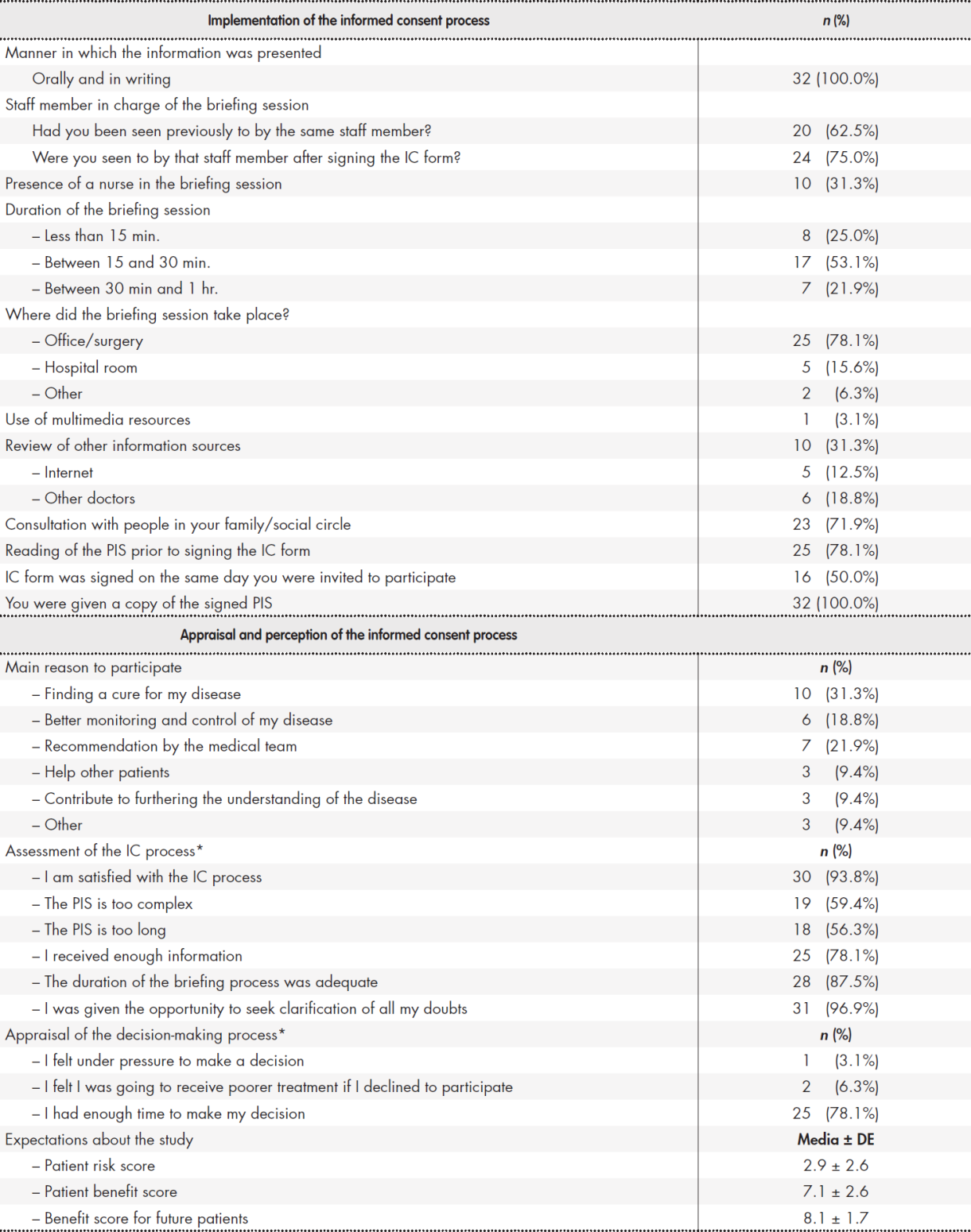

Table 3 shows the most common responses obtained in the first part of the questionnaire, where the aim was to understand the patients’ perception and appraisal of the overall IC process.

Table 3. Pilot study: responses to part 1 of the questionnaire

C: informed consent; PIS: patient information sheet. *Patients who responded agree or fully agree.

The second part of the questionnaire, which was geared toward evaluating patients’ level of understanding, produced a mean overall score of 69.5 (SD = 10) for objective comprehension and 77.4 (interquartile range (IQR) = 67.3-85.3) for subjective comprehension. Responses to questions 21, 22 and 23 in section A were analyzed separately and produced a mean score of 69.4, 66.1 y 68.8 respectively. Mean completion time was 16.6 minutes (range: 14-20). As regards acceptability, all respondents were positive about the clarity of the questions and the appropriateness of the questionnaire’s format. Further to patient feedback, it was decided to modify question 19.4, replacing the term “confidentiality” by “intimacy and privacy”. A decision was also made to highlight some words phrases in the questions to prevent respondents from following an automatic repetitive pattern in their answers. Finally, a question about the amount of information provided was removed as there was a similar question elsewhere in the questionnaire.

Reading ease: optimization and analysis

Once the pilot was over, the definitive questionnaire was designed (Appendix 1), which was made up of the following sections: general details, practical development of the IC process, appraisal of the IC process, and evaluation of patients’ level of understanding.

The reading ease analysis provided an IFSZ score of 64.34, which corresponds to an “average difficulty” grade on the INFLESZ scale.

The questionnaire was approved by La Paz hospital’s Innovation Committee and was notarized by Miguel García Gil, member of the Notarial College of Madrid on 29 November 2019. It was assigned protocol nr 214530.

Discussion

Several tools have been designed in the last few years to evaluate the IC process in the context of clinical research21,22,25-29. Although implementation of such tools undoubtedly constitutes a major development, none of them is fully aligned with the goals of this study, as they are more often than not intended to analyze specific aspects of the process such as the contents of the information provided, the understanding of such information, therapeutic misconception, or the reasons why patients agree to participate in a study. Moreover, most of the tools were developed abroad, which makes them difficult to implement without a previous adaptation process that takes into account potential differences concerning language, culture and social and healthcare conditions.

Our tool was developed to gain a better understanding of the overall

IC process from the patient’s standpoint, with a view to identifying and analyzing the strengths and weaknesses they perceive during the briefing and decision-making processes.

The questionnaire designed under this study is meant to be self-administered, which provides access to a greater number of patients and precludes the risk of interviewer bias. Unlike other similar questionnaires23,25, the survey presented here does not include open-ended questions as these pose difficulties concerning response coding and standardization, and are more burdensome for both patients and investigators.

Our questionnaire includes the translated and adapted version of the QuIC survey, which is a simple and practical way of appraising patients’ understanding of the IC process. The QuIC tool was developed specifically for oncologic studies, which may at first sight be considered to limit its application to trials related to other medical specialties. Nonetheless, as none of the questions make specific reference to cancer research, it was possible to adapt and validate the instrument for use in other kinds of trials. In this regard, all the questions included in the QuIC refer to the basic general aspects that any patient participating in a clinical trial should be aware of, regardless of the condition or medications investigated. In spite of that, we believe complementary studies should be conducted to confirm our findings and evaluate the psychometric properties of the translated and adapted version of the QuIC tool.

Our work presents a series of limitations that must be taken into account when interpreting the results obtained. Firstly, the questionnaire is exclusively aimed at evaluating the IC process in patients participating in clinical research studies. It is not meant for patients who, after being briefed and invited to participate in a study, are not finally included in it either because they decline to participate or because they do not meet some of the inclusion criteria. In addition, given that the information is based on patients’ memories, variations may appear in the results because of discrepancies with respect to what really happened.

Our tool helps understand and evaluate the IC process from the standpoint of patients invited to participate in a clinical trial. Investigators will surely find it useful both to ensure that the IC process has been correctly followed, and to identify specific clinical aspects requiring improvement.

Contribution to the scientific literature

Informed consent is one of the main pillars of research. It is not only an indispensable legal requirement to carry out any clinical trial but also an ethical imperative for healthcare professionals. The literature shows that in spite of the theoretical and regulatory efforts made to improve the briefing and consent-taking processes, a number of barriers and difficulties still exist that create a gulf between daily practice and the theoretical ideal.

The present study provides researchers with a new tool to come to grips with the realities of the informed consent process and evaluate how it works in everyday practice. Implementation of the tool presented here may be useful for designing new strategies conducive to improving the quality of the process and ensuring that consent has been obtained in accordance with the relevant ethical and legal requirements.

text in

text in