My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista de la Sociedad Española del Dolor

Print version ISSN 1134-8046

Rev. Soc. Esp. Dolor vol.24 n.5 Madrid Sep./Oct. 2017

https://dx.doi.org/10.20986/resed.2017.3582/2016

ORIGINALS

Pain management in cancer patients receiving radiotherapy: GORVAMUR study, a prospective, observational, epidemiological study

1Servicio de Oncología Radioterápica FIVO. Fundación Instituto Valenciano de Oncología. Valencia. España

2Servicio de Oncología Radioterápica. Hospital de La Ribera. Alzira, Valencia. España

3Servicio de Oncología Radioterápica. Instituto Oncológico del Sureste. Murcia. España

4Servicio de Oncología Radioterápica. Hospital San Jaime. Torrevieja, Alicante. España

5Servicio de Oncología Radioterápica. Hospital San Juan de Alicante. España

6Servicio de Oncología Radioterápica. Hospital Clínica Benidorm, Alicante. España

7Servicio de Oncología Radioterápica. Hospital IMED. Elche, Alicante. España

8Servicio de Oncología Radioterápica. Hospital La Fe. Valencia. España

9Servicio de Oncología Radioterápica. FIVO. Fundación Instituto Valenciano de Oncología. Alcoy, Alicante. España

10Servicio de Oncología Radioterápica. Hospital Clínico Universitario. Valencia. España

11Servicio de Oncología Radioterápica. Hospital Virgen de La Arrixaca. Murcia. España

12Servicio de Oncología Radioterápica. Hospital General de Valencia. España

INTRODUCTION

In the field of radiation therapy (RT) for cancer, the growing use of aggressive RT regimens means that pain poses a problem in daily clinical practice 1, so it is very important to control this pain to make the treatment more comfortable and to avoid suspending radiation therapy for this reason, with the risk of lost effectiveness it would involve 2. In patients undergoing RT with radical intent, patients may suffer acute pain associated with mucositis and epitheliopathy caused by the treatment. Furthermore, in the medium term, patients who have received radical or complementary radiotherapy may suffer painful syndromes such as brachial or lumbosacral plexopathy, radiation osteoradionecrosis or proctitis or cystitis 3. In addition to these specific situations, we should add that many oncological processes are accompanied by painful symptomatology treatable with baseline analgesic therapy. In these cases, the impact of RT may exacerbate the pain caused by the pathology itself and/or of the appearance of breakthrough pain episodes, spontaneously or associated with dysfunction caused in affected areas. In any event, recovery of analgesic control may require modification to this analgesic regimen.

Breakthrough cancer pain (BCP) is defined as an acute exacerbation of pain with sudden onset, short duration and moderate to high severity, which appears in cancer patients with chronic pain controlled therapeutically with opioid drugs 4) (5.

Recommendations for treating BCP have historically included the addition of a short-acting opioid. However, guidelines have more recently stressed the usefulness of fast-acting fentanyl. These agents have a rapid onset and short duration, which coincide with the profile of a typical BCP episode 6) (7) (8.

Data from surveys indicates that BCP is far from being optimally treated 9) (10) (11 which leads to an increase in perceived pain intensity 12, reduced patient quality of life 11 and a significant economic burden 13.

There do not exist controlled studies to measure the management, intensity and effectiveness of treatment of pain caused by cancer treatment such as RT. With this background, the main objective of this study was to analyze pain management in cancer patients undergoing RT and its impact on their analgesic control, to evaluate the effectiveness and tolerability of the analgesic treatment used, as well as patient satisfaction and its impact on their quality of life.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design

Epidemiological, observational, prospective, multicenter study of patients diagnosed with cancer, of any tumor location and stage, who required step 3 analgesic treatment for their cancer pain and who began RT (not combined with other treatments) subject to analgesic control modification by their radiotherapist. Patients were recruited from 15 Radiation Oncology Services at centers in the regions of Valencia and Murcia from May 2013 and the period of recruitment lasted until December 2014. Each investigator consecutively recruited an average of 10 patients who visited their clinic and who met all the selection criteria.

Inclusion criteria were: ambulatory, above 18 years old, diagnosed with cancer (any location) regardless of stage, who were to begin treatment with radiation therapy (RT). Additionally, they had to have a life expectancy greater than 6 months, step 3 baseline analgesic medication to treat pain that, in the radiotherapist's opinion, could be altered and who authorized their participation in the study by signing their informed consent in writing.

The study excluded patients who, despite beginning treatment with RT, did not have step 3 analgesic treatment initiated and who, in the investigator's opinion, did not have sufficient cognitive capacity, presented sensory or psychiatric disability or linguistic barriers that prevented or obstructed their participation and collaboration in taking part in the study.

A monitoring period of three months was established, with a baseline control that coincided with the first RT session, and two monitoring visits (after one month and at three months after initiating RT).

The investigators at each center collected information in a databook designed for the purpose, which included information from each patient's clinical history and from a direct interview with them. For complete monitoring, a diary was attached for patients to write down any breakthrough pain episode with its respective characteristics, together with the medication taken, over a period of three months.

Variables analyzed

The visit at the beginning of the study collected: patients' sociodemographic data (sex and age), baseline characteristics of the cancer process (tumor location, stage and general state of the cancer patient - ECOG score), pain level (Brief Pain Inventory [BPI], Visual Pain Scale), baseline analgesic treatment (type and dose), and dose of RT used. Throughout monitoring, data on the analgesic treatment collected, regarding both baseline and rescue treatment (type, dose, initiation date and final date of each treatment or dose). Results were collected regarding the different analgesic treatment strategies throughout monitoring, which included: a) patients for whom the baseline analgesic treatment is maintained; b) patients for whom the baseline analgesic treatment is reinforced or modified with an analgesic regimen of longer or more intense duration; c) patients for whom the baseline analgesic regimen is increased with an on-demand, fast-acting analgesic for breakthrough pain episodes, and d) patients for whom the baseline analgesic regimen is increased with a fast-acting analgesic in a programmed way to prevent the occurrence of breakthrough pain episodes associated with dysfunction caused in affected areas.

Data was also collected on the safety of the treatments used (adverse reactions) during the whole monitoring period.

Analgesic control was defined in terms of relative change from baseline to one month/three months' monitoring of maximum pain intensity measured on the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) of the BPI (Brief Pain Inventory). Minimum clinically significant changes correspond to ±15%. Standardized amount of pain caused by breakthrough pain episodes was also evaluated (minimum significant difference, for a significance level of 95%, corresponds to ±1.96).

Pain was characterized at one month and at three months from initiation of RT by evaluating the change in the dimension of BPI pain and in the amount of pain caused by breakthrough pain episodes throughout the patient monitoring period (time by intensity). Additionally, patient satisfaction level was assessed at one month and when monitoring ended, according to the satisfaction questionnaire (with Likert-type responses) and quality of life using the EuroQol-5D scale.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of 150 patients was assessed, assuming that baseline characteristics explain 15% of variance in the dependent variable (r2 of the baseline with baseline factors = 0.15), and that management strategies explain a minimum of 10%; that the desired significance level was 95%, with a power of 90% (130 patients); and monitoring losses would be around 10%. Quantitative variables were described by: mean, standard deviation, SD 95% (mean confidence interval 95%), median, interquartile range and minimum and maximum value. Qualitative variables were described by frequency and percentage. Comparison of qualitative variables between two or more groups was carried out using the Chi-squared test and/or Fisher's exact test. To determine whether quantitative variables fit a normal distribution, Kolmogorov Smirnoff's test or the Shapiro-Wilk test were used. All statistical tests are considered bilateral and level of significance is taken as α= 0.05.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was presented for evaluation by the clinical investigation Ethics Committee of the foundation Instituto Valenciano de Oncología, which approved the study on 2 October 2012. Subsequently, this committee was requested to enlarge the number of centers, receiving approval for this measure on 6 May 2013. In addition to this committee, due to the study's prospective nature, it had to be evaluated by committees in the communities of Valencia and of Murcia. In the case of 4 participating centers, re-evaluation by the respective ethics committees was required.

RESULTS

Of the 15 centers envisaged for participation, three did not contribute patients and only one of them contributed the 10 patients planned according to the study protocol. Finally, and after extending the recruitment period four times consecutively, information on a total of 60 patients was collected (response rate 40%), one of which did not meet the selection criteria, so the eligible population numbered 59 patients. All the patients signed their informed consent. However, upon verifying the database, a further 3 patients were detected who did not meet the selection criteria (no treatment with step 3 opioids) and 7 more in whom the date of their baseline visit deviated from protocol conditions as regards radiotherapy initiation date (baseline visits carried out before or after one month from date of initiating RT). Therefore, the final sample consisted of 49 patients (33% of intended size). Figure 1 shows the study flow-chart.

Baseline characteristics

Table I summarizes the characteristics of patients, characterization of the oncological process and pain at baseline visit. 72.3% of this study's patients were men. Mean patient age was 63.7 ± 11.5 years old (range 32-84). 26.5% of patients had a tumor in the lung and 28.6% in the head and neck; and in the rest of patients, location varied greatly (3 colon/rectum and breast, 2 prostate and pancreas and 1 kidney, bladder, uterus, esophagus and skin; in 4 cases location was unknown). 70.8% were stage IV cancers. Median (P25-P75) time elapsed from diagnosis was 4.0 (2.5-13.5) months. According to the ECOG scale (0-4), 17.0% of patients were fully active, 51.1% were limited in carrying out strenuous physical activity, 23.4% were treated as ambulatory and were capable of self-care, 8.5% had limited ability to care for themselves and no patient was wholly incapable.

Table I BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENTS AND PAIN

*The low number of observations makes it advisable to use the median and the interquartile range to describe these variables. 1: calculated as the sum of worst pain, slightest and average in the last 24 hours and current pain. 2: calculated as the average of 7 items assessing the impact of pain on daily activities.

SD: standard deviation. VAS: visual analogue scale. RT: radiotherapy. All except one of the patients reported pain at the time of the baseline visit. Primary tumor was the cause of pain in 20.8%, metasteses in 54.2% and RT in 22.9%. The median (P25-P75) number of episodes in the previous month was 56.2 (14.8-90) and the median number of crises per day was 3.0 (2-4.5). Of the 48 patients with pain, 60.4% were receiving treatment for breakthrough pain. Fentanyl was the most frequently used active agent (70.4%), followed by morphine or hydromorphone (14.8%), oxycodone (7,4%), tramadol (3,7%) and NSAIDs or dipyrone (3.7%). According to the results of BPI questionnaire (Table I), pain severity at baseline on a 0-40 scale, obtained as the sum of worst pain, slightest, average and current pain, was 18.9 ±7. Maximum pain experienced in the previous 24 hours on a 0-10 scale was 7.8 ±2.1, and the impact of pain on daily activities on a 0-10 scale, calculated as the average of the 7 articles that evaluate this dimension, was 4.9 ±2.6.

As regards characterization of baseline RT, all patients began external RT. The most frequent locations were: neck (28.6%), thorax (22.4%), spine (20.4%), pelvis (16.3%) and skull (12.2%). A dose of 300 cGy was used in 20.8% and 400 cGy in 6.3%; the rest (72.9%) received other doses, with a median (P25-P75) of 500 (200-6,000). In the visit at 1 month, 38.7% received RT at that visit. Doses of 300 cGy were used in 8.3%, and in the remaining 91.7% other doses were used, with a median (P25-P75) of 212 (200-350).

Table II and Table III summarize baseline analgesic treatment. The most frequently prescribed rescue treatment was fentanyl (77.6% of patients) with a dose of 200 (100-400), and the most common route of administration was sublingual (57.9%; at dose 200 [100-400]), followed by inhaled (15.8%; at dose 400 [162,5-850]); in 23.7% the route of administration was not specified. As a second rescue drug prescribed, transdermal fentanyl was administered in 2 patients and metamizole in one. 16,3% of patients had no rescue treatment prescribed.

Table III BASELINE RESCUE TREATMENT (N = 49). DRUGS USED AND DOSE/DAY

Min.: minimum. Max.: maximum. P25: percentile 25. P75: percentile 75. na: not applicable. Dose/day does not follow normal distribution or they show a small number of observations, making it advisable to use the median and interquartile range to describe them

Main objective

Table IV summarizes the characteristics of pain in visits at month 1 and month 3, in addition to treatment and different treatment strategies. In the visit at month 1, no rescue treatment was prescribed in 23.3% of patients. In those who did receive rescue medication, mean use since previous visit was 24.8 ±20.0 times. Change of treatment or dose occurred in 74.2% of patients who attended the visit after the first month. In 82.6% of cases, fentanyl was the drug used after the change, and sublingual was the most common route of administration (31.6% of cases where fentanyl was used). As regards treatment in the month 3 visit, rescue medication was prescribed to 60% of patients and mean use since the previous visit was 38.6 ±29.9 times. Change of treatment or dose took place in 20.0% of patients who attended the month 3 visit and in 66.6% of cases fentanyl was the drug used after the change. Sublingual (50%) and inhaled (50%) were the only routes of administration used.

Table IV CHARACTERIZATION OF PAIN AND TREATMENT IN THE VISIT AT ONE MONTH AND AT THREE MONTHS

* The small number of observations makes it advisable to use the median and the interquartile range to describe these variables. 1: calculated as the sum of worst, slightest and average pain in the last 24 hours and pain experienced right now. 2: calculated as the average of 7 items that assess the impact of pain on daily activities. SD: standard deviation. VAS: visual analogue scale.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the mean and median values of the relative change in maximum pain and amount of pain between visits. The outcomes show a decrease in maximum pain and in amount of pain in the visit at one month and at three months with respect to the baseline visit. Between the visit at 1 month and the visit at 3 months, the relative change is smaller.

Table V describes the relative change in maximum pain and in amount of pain among the 3 visits of the study according to pain management strategy. None of the 3 comparisons found an association between the relative change in maximum pain and the analgesic strategy, so the option to carry out a multivariate analysis was discarded. In analyzing the relative change in amount of pain according to analgesic strategy, an association was found between relative change in maximum pain and analgesic strategy (p = 0.036) between baseline visit and month 3.

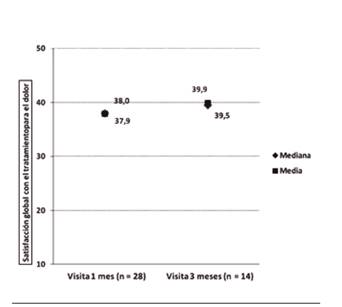

Patient satisfaction

Figure 4 shows overall satisfaction with treatment, with high mean and medium values and very close to each other in both visits, though slightly higher at the 3-month visit. Results of the satisfaction test show a moderate to high satisfaction level with episode control, route of administration, tolerability, effectiveness, effect speed and overall satisfaction, with an improvement at the 3-month visit with respect to the 1-month visit (Table VI). No association was found between patient satisfaction and treatment strategy.

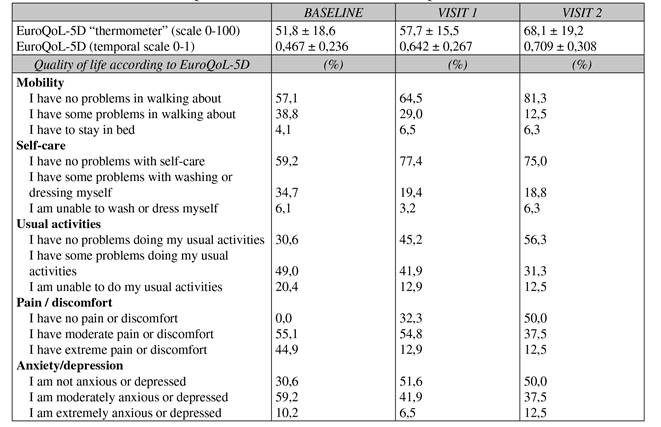

Quality of life and health gain

Figure 5 and Figure 6 show the relative change in quality of life and health gain among the three visits. Positive changes show greater quality of life between visit 1 and baseline and visit 3 and baseline in both parameters. As regards treatment strategies, no association was found between relative change in patient quality of life or health gain (Table V). Table VII shows the results of the EuroQoL-5D test in the three visits studied, finding an improvement in the two visits compared with baseline and a significant drop in the percentage of patients with a high perception of pain or pain-associated discomfort.

Tolerability

Only 2 patients suffered an adverse reaction during the study. The first consisted of "drowsiness" of slight intensity, related with increased drug dose (transdermal fentanyl); no action was taken as a result of the AR. The second adverse reaction consisted of "disorientation" of moderate intensity, related with oxicodone administration. It had a duration of 19 days until the drug was suspended. The outcome of both was improvement.

DISCUSSION

Breakthrough pain in cancer patients who are undergoing RT, according to this study's findings, shows a greater prevalence than as observed in cancer patients in our area not subjected to radiation therapy 14, with major repercussions on patients' general state and quality of life, as well as on the daily clinical practice of Radiation Therapy Services, as regards its management and possible alteration to the proper administration of radiotherapy. Accordingly, it is important to know these patients' specific profile, to characterize their pain and to evaluate the different treatment strategies available to guarantee effective treatment and optimal quality of life. This is the first observational study to focus on pain management in the field of Radiation Oncology care. The profile of patients affected by this pain selected for RT is mostly men, above 60 years old, who suffer from stage 4 cancer diagnosed during the previous year, frequently located in the lung, head and neck. Tumor locations coincide with the findings of other international studies regarding the type of tumor location with the greatest prevalence in breakthrough cancer pain 15. The number of initial daily breakthrough pain crises is higher than as mentioned in other cancer studies of patients not subjected to RT, but with a similar level of initial intensity (VAS scores of 7-8) which returned to moderate pain levels after more than 15 minutes of crisis in most cases 14. Considering the sum of baseline pain and pain caused by breakthrough crisis, patients reported daily activities to be affected at levels mid-way between zero impact and maximum possible 16 and moderate levels of anxiety or depression that, added to the high prevalence of pain, reflected quality of life levels well below those of the general Spanish population (51.8 compared with 77.53 in the general population) 17. In subsequent reviews, after establishing different analgesic strategies to control pain based fundamentally on fentanyl, the percentage of patients reporting pain was reduced, the severity of this pain was reduced, the pain intensity's effect on daily activities decreased progressively and a greater percentage of patients reported that anxiety/depression symptoms had disappeared and that quality of life had improved. These results coincide with data recently published regarding patients with BCP treated with fentanyl, where the dimensions of physical activity, anxiety and depression improved significantly after treatment 18.

As regards RT's possible impact on patients' critical state, more than a third of cases reported pain attributable to the effects of RT, 25% associated with radiation mucositis and 18% to radiodermatitis 19) (20. However, there is not sufficient data to make an evaluation regarding the effect of RT on changes in pain assessment, whether a possible increase in pain due to side effects of the radiation therapy or a possible beneficial antialgic effect of the radiation (pain originating from the tumor).

We should make special mention of levels of patient satisfaction with the treatment received to control pain episodes based on different routes of fentanyl administration, predominantly sublingual, with high-to-very-high satisfaction levels regarding its simple, convenient route of administration, very good tolerance, effective, fast relief that coincides with the findings of other studies on managing BCP with different fentanyl preparations 21) (22. The analgesic regimen was managed dynamically, adapted to patients, with changes and adjustments distributed between reinforcing and decreasing baseline analgesia, or rescue analgesia or reinforcing the combined strategy of both. However, in personalizing management strategies, the dispersion of cases into different strategies together with the drop in the number of patients available for monitoring does not allow assessment of their different impact, and we may only assert that considerable variability exists in analgesic management, that reinforcement regimens reduce pain, and that in cases where reinforcement is necessary, fentanyl is the medication most used, both to reinforce the baseline analgesia and to treat breakthrough pain

One of this study's main limitations has been the small sample size, not just in the number of patients, which was reduced to 49 patients (a third of what was proposed), but also in the loss of observations in visits by patients who made up the sample. With this number of observations, the power to find univariate association between the variables derived from the study and treatment strategy is very limited. Another limitation is heterogeneous data collection regarding dose of RT used, so the data must be interpreted with caution. We should also consider the limitation arising from the derived variable "Relative change in amount of pain" based on "Intensity of pain in last breakthrough pain crisis".

CONCLUSIONS

Breakthrough pain in cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy constitutes a highly prevalent symptom. There is no predominant analgesic strategy for managing these patients, but fentanyl is the drug most frequently prescribed. Analgesic treatment based on this drug to treat breakthrough pain favorably affects patients' general state and quality of life, tolerability of treatment is excellent and patients report a high level of satisfaction.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study has been carried out funds contributed (grant) by Kyowa Kirin Farmaceútica SLU. We would like to thank all the oncology radiotherapists who took part in the study for their participation: José Luis Mengual, José Luis Monroy Antón, Adriana Fondevilla Soler, Rosa Cañón, Gabriel Vázquez Pérez, Manuel Santos Ortega, Pablo Soler, Francisco J. Martínez Arcelus, Araceli Moreno Yubero, Esther Jordá, Ramón García Fernández, Amparo González Sanchís, Rosa Algás Algás, Miguel Soler Tortosa, Juan Salinas Ramos, Ignacio Azinovic Gamo, M.ª Dolores Ruiz Sánchez, Francisco Andreu Martínez and Gorka Nagore. We would also like to thank María Dolores Aguilar, Antonio González, Iván Alcolea, Ana Ortega and Ana Zabaljauregui, who provided support for the design, setup, coordination, analysis and medical writing on behalf of OXON Epidemiology, for the Gorvamur group.

REFERENCES

1. Konopka-Filippow M, Zabrocka E, Wójtowicz A, Skalij P, Wojtukiewicz MZ, Sierko E. Pain management durin radiotherapy and radiochemotherapy in oropharyngeal cáncer patients: single-institution experience. Int Dent J 2015;65(5):242-8. DOI: 10.1111/idj.12181. [ Links ]

2. Bell BC, Butler EB. Management of predictable pain using fentanyl pectin nasal spray in patients undergoing radiotherapy. J Pain Res 2013;6:843-8. doi: 10.2147/jpr.554788. [ Links ]

3. Oliai C, Fisher B, Jani A, Wong M, Poli J, Brady LW, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for radiation-induced cystitis and proctitis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;84(3):733-40. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.12.056. [ Links ]

4. Portenoy RK, Hagen NA. Breakthrough pain: definition, prevalence and characteristics. Pain 1990;41(3):273-81. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90004-W. [ Links ]

5. Davies AN, Dickman A, Reid C, Stevens AM, Zeppetella G; Science Committee of the Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland. The management of cancer-related breakthrough pain: recommendations of a task group of the Science Committee of the Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland. Eur J Pain 2009;13(4):331-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.06.014. [ Links ]

6. National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN Clinical Practice. Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Adult Cancer Pain. Version 1.2013. 2013. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. Accessed August 29, 2016. [ Links ]

7. Caraceni A, Davies A, Poulain P, Cortés-Funes H, Panchal J, Fanelli G. Guidelines for the management of breakthrough pain in patients with cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2013;11(Suppl. 1):S29-S36. [ Links ]

8. Caraceni A, Hanks G, Kaasa S, Bennett MI, Brunelli C, Cherny N, et al. Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. Lancet Oncol 2012;13(2):e58-e68. DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70040-2. [ Links ]

9. Greco MT, Corli O, Montanari M, Deandrea S, Zagonel V, Apolone G. Epidemiology and pattern of care of breakthrough cancer pain in a longitudinal sample of cancer patients. Results from the Cancer Pain Outcome Research Study Group. Clin J Pain 2011;27(1):9-18. DOI: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181edc250. [ Links ]

10. Mercadante S, Costanzo BV, Fusco F, Buttà V, Vitrano V, Casuccio A. Breakthrough pain in advanced cancer patients followed at home: a longitudinal study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38(4):554-60. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.12.008. [ Links ]

11. Breivik H, Cherny N, Collett B, de Conno F, Filbet M, Foubert AJ, et al. Cancer-related pain: a pan-European survey of prevalence, treatment, and patient attitudes. Ann Oncol 2009;20(8):1420-33. DOI: 10.1093/annonc/mdp001. [ Links ]

12. Dickman A. Basics of managing breakthrough cancer pain. Pharm J 2009;283:213e216. [ Links ]

13. Fortner BV, Demarco G, Irving G, Ashley J, Keppler G, Chavez J, et al. Description and predictors of direct and indirect costs of pain reported by cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;25(1):9-18. DOI: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00597-3. [ Links ]

14. Gómez-Batiste X, Madrid F, Moreno F, Gracia A, Trelis J, Nabal M. Breakthrough cancer pain: Prevalence and characteristics in patients in Catalonia, Spain. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24(1):45-52. DOI: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00421-9. [ Links ]

15. van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol 2007;18(9): 1437-49. DOI: 10.1093/annonc/mdm056. [ Links ]

16. Katz N. The impact of pain management on quality of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24(1 Suppl):S38-47. [ Links ]

17. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Encuesta Nacional de Salud. España 2011/12. Calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en adultos: EQ-5D-5L. Serie Informes monográficos nº 3. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad, 2014. [ Links ]

18. Guitart J, Vargas MI, De Sanctis V, Folch J, Salazar R, Fuentes J, et al. Sublingual fentanyl tablets for relief of breakthrough pain in cancer patients and association with quality-of-life outcomes. Clin Drug Investig 2015;35(12):815-22. DOI: 10.1007/s40261-015-0344-0. [ Links ]

19. Xiao C, Hanlon A, Zhang Q, Movsas B, Ang K, Rosenthal DI, et al. Risk factors for clinician-reported symptom clusters in patients with advanced head and neck cancer in a phase 3 randomized clinical trial: RTOG 0129. Cancer 2014;120(6):848-54. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.28500. [ Links ]

20. Xiao C, Hanlon A, Zhang Q, Ang K, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tan PF, et al. Symptom clusters in patients with head and neck cancer receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Oral Oncol 2013;49(4):360-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.10.004. [ Links ]

21. Torres LM, Revnic J, Knight AD, Perelman M. Relationship between onset of pain relief and patient satisfaction with fentanyl pectin nasal spray for breakthrough pain in cancer. J Palliat Med 2014;17(10):1150-7. DOI: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0089. [ Links ]

22. Rauck R, Parikh N, Dillaha L, Barker J, Stearns L. Patient satisfaction with fentanyl sublingual spray in opioid-tolerant patients with breakthrough cancer pain. Pain Pract 2015;15(6):554-63. DOI: 10.1111/papr.12225. [ Links ]

Received: January 30, 2017; Accepted: March 16, 2017

text in

text in