Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista de la Sociedad Española del Dolor

versión impresa ISSN 1134-8046

Rev. Soc. Esp. Dolor vol.26 no.1 Madrid ene./feb. 2019

https://dx.doi.org/10.20986/resed.2018.3658/2018

ORIGINALS

Psychosocial factors in chronic cancer pain: a Delphi study

1Servicio de Hematología. Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII de Tarragona, Spain

2Cátedra de Dolor Infantil URV-Fundación Grünenthal. Unidad para el estudio y tratamiento del dolor (ALGOS), Spain

3Centre de Recerca en Avaluació i Mesura del Comportament. Spain

4Institut d'Investigació Sanitària Pere Virgili. Spain

5Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Spain

6Departamento de Psicología, Universitat Rovira i Virgili. Tarragona, Spain

INTRODUCTION

Approximately nine million people are diagnosed with cancer worldwide each year 1, and pain 2,3 is one of their main problems. Indeed, the World Health Organization estimates that one third of cancer patients experience pain in the initial stages of the disease, between 50 and 70% of pain cases will be present in the intermediate stages, and between 75 and 90% of them will be present in the most advanced stages 4.

Furthermore, studies conducted with cancer survivors place the prevalence of chronic pain at 30 to 60% 5, with indications of high morbidity and serious consequences on their quality of life 6. The available studies do not allow elucidating with precision which factors determine the onset of pain or its impact on these patients 7,8. There is also no consensus about which factors are responsible for chronic cancer pain; therefore, it is difficult to propose efficient actions to prevent or mitigate their impact on patients' lives. Despite abundant literature is found regarding factors related to chronic pain; in general, these studies analyze specific domains and in isolation, such as the influence of psychological variables, e.g. depression 9, or pathophysiological factors, such as the study of the Diffuse Noxious Inhibitory Controls (DNIC) [10] system. And even worse: there are many contradictory results. For example, while some studies point to the type of surgery used as one of the factors responsible for chronic cancer pain 11, other studies did not find any relationship between the surgical technique and the persistence of pain 12.

The identification of factors responsible for the chronicity of pain, especially modifiable factors, would allow optimizing health resources through the development of specific treatments to mitigate the impact of pain, perhaps to prevent pain, and to help to improve quality of life of these people and the of their relatives.

The objective of this study was to identify the most important risk factors for chronicity of cancer pain according to experts. As a secondary objective, and in an exploratory way, factors that could function as protectors of the impact of chronic cancer pain in lives of these people were studied too.

METHOD

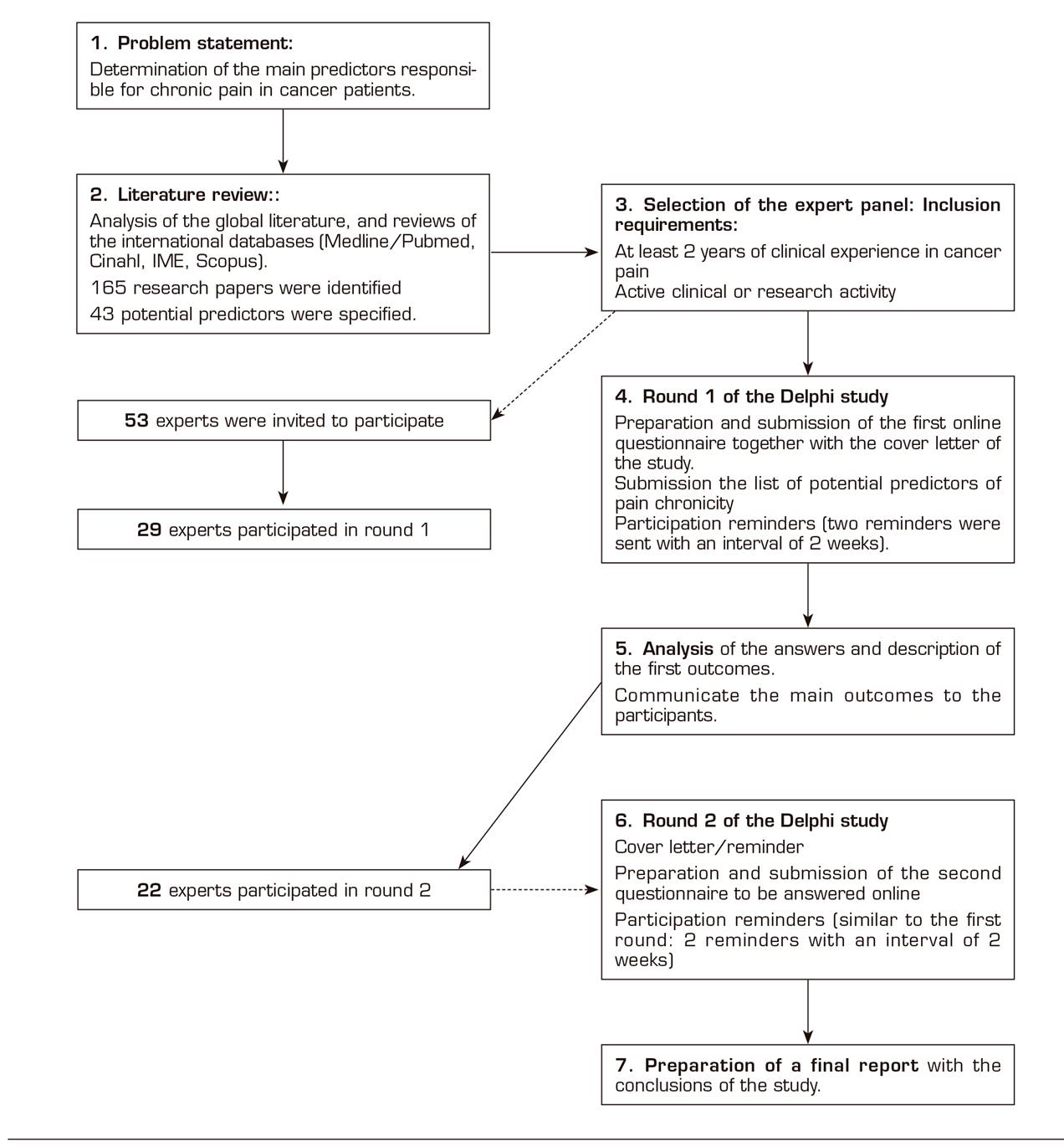

The Delphi methodology was used to identify factors predicting chronic cancer pain. This method involves selecting a group of experts who are inquired by using questionnaires in an iterative process until consensus on answers is reached 13. The surveys are anonymous to avoid the influences of some participants on others 14. Figure 1 shows the different stages of this procedure.

Participants: the panel of experts

The group of experts participating in this study consisted of professionals with training and expertise in cancer pain. Following the suggestions of previous similar experiences successfully concluded (15), the experts had to fulfill one of the following criteria to participate in this study: 1) at least 2 years of clinical experience in cancer pain; and 2) active research activity for at least two years. Specific information about the participants in the panel is presented in the results section.

Predictive factors for chronic cancer pain

A first list of predictive factors was made from 2 sources of information. First, a literature review of was conducted, searching publications on chronic pain in Medline/Pubmed, CINAHL, the Spanish Medical Index (IME), Google Scholar and Scopus. A combination of the following keywords was used as a search strategy: cancer, chronic pain, predictive factors and Delphi poll, using the Boolean operators NOT, AND and OR to filter or expand the articles based on the obtained results. This literature review allowed identifying a total of 165 research papers, from which 42 potential predictors were derived. This first list was sent to the panel of experts in order to be supplemented or modified according to their criteria (Table 1). These factors were functionally defined for their correct identification.

Protective factors for chronic cancer pain

The consultation on protective factors was posed using an open-ended question: "Which do you consider would be protective factors regarding chronic pain? Please, list the main aspects that you consider would have a preventive or protective effect". This question and the information related were provided during the second round.

Procedure: Delphi rounds

The procedure requires asking as many rounds of questions as necessary until reaching consensus (that is, stability in the answers) among the experts 16. In this study, similarly to previous studies with similar aims 15, stability was established when the item had been identified as a predictor by a number equal to or greater than 75% of the participants. Two rounds were enough. In general, studies using this methodology reach consensus with two rounds of questions, although it can vary between two and five 13.

Round 1

The first round of questions had a first part in which sociodemographic data were requested: profession, specialty, years of experience, type of activity (clinical, research or both), sex and age. And a second part in which the experts had to answer the following questions: 1) According to your experience and knowledge, which factors do you think influence the appearance of chronic pain in cancer patients? ; 2) Which of the following categories of factors (biological, emotional, cognitive, behavioral) do you think have a greater influence on the onset of chronic cancer pain?, and 3) do you consider that the nature or type of pain influences the risk of chronic pain? If the answer is affirmative, please, indicate what type of pain you consider to be at greatest risk of chronicity.

A total of 53 experts were invited to participate. Those who accepted were asked to answer the survey online within 3 weeks and 2 reminders were sent. The task required about 30 minutes to be completed. The results were analyzed to verify the percentage of agreement in the responses of the participants. It consisted of a descriptive analysis, with calculation of frequencies and percentages for the different variables of the study.

Round 2

Two months after initiating the first round, the experts were informed of the results of the first round. The list of potential predictors was again submitted for consideration, adding those suggested factors that were not included in the original list. The questions were answered by choosing the single option stating "agree or "disagreement" or "yes"/"no" on the item posed, requesting the justification of their choice. In this round, the specific question related to protective factors was inquired. Again, to encourage participation, two reminders were sent throughout the four weeks this phase was active.

RESULTS

Round 1

A total of 53 experts were invited to participate. Although the initial group of experts had a larger number of women than the second group, the final percentage of participants was similar (59% women vs. 41% men). Table 2 shows the characteristics of the participants. The group of experts participating in the study was presumably multidisciplinary, with extensive experience and with a clinical profile, but also a researcher profile in a high percentage. Regarding the main objective of this study, that is, to identify the predictors of chronic cancer pain, the panel of experts agreed that the main factors include both biological and psychosocial factors, specifically: 1) the cancer process, progression or infiltration of the disease; 2) poorly controlled pain; 3) neurotoxicity or injury of the nervous system; 4) intensity of pain, and 5) emotional or psychological factors and, among these, catastrophic thoughts stand out.

Table 3 shows the main predictors of chronic pain identified by the experts. Furthermore, the importance of factors related to the surgical process are underscored in cancer patients undergoing surgery, the following factors are highlighted: 1) any type of preoperative chronic pain in conjunction with psychosocial factors, 2) the type of surgery and 3) the requirement of a more invasive surgery and the intensity of acute postoperative pain recorded, among others (Table 3). Regarding whether the nature or type of pain was a significant predictor of the risk of chronicity, 76% considered that neuropathic pain presents the highest risk.

Round 2

All those experts who agreed to participate and correctly completed the questionnaire in phase 1 of the study (n = 29) were invited to the second round. A total of 22 (76%) out of 29 experts answered the questionnaire; the characteristics of the group of participants in round 2 were almost the same as in round 1. In round 2, the responses showed that the most important factors for the development of chronic cancer pain are: cancer process and poorly controlled pain, factors that achieve a 100% consensus, followed by neurotoxicity or nervous system injury produced by chemotherapy treatment (82%) and pain intensity (77%). The psychosocial factors that stand out with a consensus higher than the criterion are: anxiety (95%), depression (91%), negative thoughts and catastrophizing (86%) and psychological predisposition (82%).

Regarding the surgical predictors, all the experts considered that the main risk factors were, first, the preoperative chronic pain of any type and with similar importance to the psychosocial factors, followed by the type of surgery and a more invasive surgery.

In the case of the protective factors for chronic cancer pain, the largest consensus is in relation to the factors linked to family, social and professional support and to certain personality characteristics of the patient. The effective and adequate analgesia, adapted individually to each patient and the early initiation of analgesia are highlighted in cancer patients undergoing surgery (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

The main objective of this study was to identify the most important risk factors for chronic cancer pain according to experts. The results obtained are consistent with other available studies on the biopsychosocial model of pain 17, this study postulates that chronic pain is a result of the interaction of multiple physical, emotional, behavioral and even social factors.

A significant contribution of the present study is that it shows that most of the identified predictive factors are amendable and, therefore, susceptible to be modified by specific treatments. For example, it has been shown that catastrophic thoughts, anxiety or attitudes towards pain that are identified in this study as predictors of chronic cancer pain change after participating in treatment programs 17. Similarly occurs with some of the most relevant physical factors. For example, pain intensity can be modulated and controlled by well-established treatments 18. Overall, therefore, the results of this study, consistently with other studies 19,20), emphasize the need to train these patients as soon as possible in strategies to cope with pain and its effects.

The present study also provides new information regarding protective factors for chronic cancer pain. In addition, consistently with those studies, these factors are also moldable and, therefore, susceptible to being incorporated into the baggage of coping strategies of patients, for example through education programs. Although in this case, it is an exploratory study, the results are consistent with those published for other groups with different ages and pain problems 21, and this consistency could be pointing out the validity of such findings.

This study is not exempt from some limitations that should be considered for a fair weighting of the results. First, the representativeness of participants. In fact, we do not know if the results would have been the same if we had counted on other experts. However, it was a group of professionals with extensive experience allowing us to anticipate the relevance of their judgments. In addition, the participant number of experts was appropriate (a minimum of 7 and a maximum of 30 22 is recommended and the dropout rate was low in both rounds.

Despite the limitations, the results of this study provide new information about both predictive and protective factors for chronic pain in cancer patients. These results raise important clinical implications to improve patient care. Consistently with current models, these results confirm that the treatment of people with chronic pain should be expanded to include the different levels and intervention units making up the experience of pain. Therefore, for example, in addition to considering the traditional physical factors (eg, pain intensity), it is also essential that the treatments incorporate the training of skills to modify negative thoughts or attitudes related to pain and its management, and not only as an alternative to reduce or eliminate the impact of chronic pain, but also as a proposal to prevent pain and disability in cancer patients. This approach would also be supported by recent evidence showing the relationship between negative attitudes and the impact of pain in both children and adults 23,24 and how treatments aimed at modifying this type of thinking are able to improve not only specific cognitions about pain, but also the physical characteristics of pain and personal functioning and social adjustment of these patients 25.

Future research studies should specifically examine the factors identified in the present study. If these results are confirmed, we could conclude that clinical procedures should be aimed at an early identification and detection of the factors triggering chronic pain by using tools that allow evaluating this risk, as well as to promote the factors that are considered protective. For example, a brief questionnaire could be developed to identify cancer patients at risk of chronic pain, so that those patients in such situation could participate in programs aimed at reducing or eliminating the likelihood of pain persisting over time, and to reduce the impact of pain on the quality of life of patients and their families. These studies should be developed based on explicit conceptual models of pain, and test the hypotheses that are built on them.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the experts who participated in this study.

REFERENCES

1. Reyes D, González JC, Mohar A, Meneses A. Epidemiología del dolor por cáncer. Rev Soc Esp Dolor 2011;18(2):118-34. [ Links ]

2. Brown MR, Ramirez JD, Farquhar-Smith P. Pain in cancer survivors. Br J Pain 2014;8 (4):139-53. DOI: 10.1177/2049463714542605. [ Links ]

3. Galán S, de la Vega R, Tomé-Pires C, Racine M, Solé E, Jensen MP, et al. What are the needs of adolescents and young adults after a cancer treatment? A Delphi study. Eur J Cancer Care 2017;26(2). DOI: 10.1111/ecc.12488. [ Links ]

4. Organización Mundial de la Salud, Informe Mundial de OMS. Prevención de las enfermedades crónicas: una inversión vital, Ginebra, OMS, 2005 [Consultado el 23 de marzo de 2016]. Disponeble en: http://www.who.int/chp/chronic_disease_report/contents/en/ [ Links ]

5. Van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ, de Rijke JM, Kessels GA, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. Prevalence of pain in patients with cáncer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol 2007;18(9):1437-49. [ Links ]

6. Elliott J, Fallows A, Staetsky L, Smith P, Foster C, Maher E, et al. The health and well-being of cancer survivors in the UK: findings from a population-based survey. Br J Cancer 2011;105(Suppl 1): S11-S20. DOI: 10.1038/bjc.2011.418. [ Links ]

7. Mirabile A, Airoldi M, Ripamonti C, Bolner A, Murphy B, Russi E, et al. Pain management in head and neck cancer patients undergoing chemo-radiotherapy: Clinical practical recommendations. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2016;99:100-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.11.010. [ Links ]

8. Balleyguier C, Arfi-Rouche J, Haddag L, Canale S, Delaloge S, Dromain C. Breast pain and imaging. Diagn Interv Imaging 2015;96(10):1009-16. DOI: 10.1016/j.diii.2015.08.002. [ Links ]

9. Chopra K, Arora V. An intricate relationship between pain and depression: clinical correlates, coactivation factors and therapeutic targets. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2014;18(2):159-76. DOI: 10.1517/14728222.2014.855720. [ Links ]

10. May A, Büchel C. Pain contra pain: the concept of DNIC. Schmerz 2010;24(6):569-74. DOI: 10.1007/s00482-010-0985-0. [ Links ]

11. Bruce J, Thornton AJ, Powell R, Johnston M, Wells M, Heys SD, et al. Psychological, surgical, and sociodemographic predictors of pain outcomes after breast cancer surgery: a population-based cohort study. Pain 2014;155(2):232-43. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.09.028. [ Links ]

12. Masselin-Dubois A, Attal N, Fletcher D, Jayr C, Albi A, Fermanian J, et al. Are psychological predictors of chronic postsurgical pain dependent on the surgical model? J Pain 2013;14(8):854-64. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.02.013. [ Links ]

13. Landeta J. El Método Delphi. Una técnica de previsión para la incertidumbre. Barcelona: Ariel; 1999; p. 21. [ Links ]

14. Godet M. Manuel de Prospective Strategique: L'art et la méthode. Paris: Dunod; 2007. [ Links ]

15. Miró J, Huguet A, Nieto R. Predictive factors of chronic pediatric pain and disability: a Delphi poll. J Pain 2007;8(10):774-92. [ Links ]

16. Cegarra J. Metodología de la investigación científica y tecnológica. Madrid: Ediciones Díaz de Santos; 2011. p. 350. [ Links ]

17. Miró J. Dolor crónico. Bilbao: Desclée de Brower; 2003. [ Links ]

18. Morley S, Williams A. New developments in the psychological management of chronic pain. Can J Psychiatry 2015;60(4):168-75. [ Links ]

19. Miró J, Raich RM. Personality traits and pain experience. Pers Indiv Dif 1992;(13): 393-413. [ Links ]

20. Miró J, Gertz KJ, Carter GT, Jensen MP. Pain location and functioning in persons with spinal cord injury. PM&R 2014;6(8):690-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.01.010. [ Links ]

21. Miró J, Nieto R, Huguet A. Predictive factors of chronic pain and disability in whiplash: a Delphi poll. European Journal of Pain 2008; 12(1):30-47. [ Links ]

22. Varela-Ruiz M, Díaz-Bravo L, García-Durán R. Descripción y usos del método Delphi en investigaciones en el área de la salud. Inv Ed Med 2012;1(2):90-5. [ Links ]

23. Díez A, Pérez-Fernández E, Castarlenas E, Miró J, Reinoso-Barbero F. Concordancia en pacientes con dolor crónico secundario a enfermedades pediátricas entre la autovaloración y las puntuaciones reportadas por sus padres. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2017;64(3):131-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.redar.2016.06.007. [ Links ]

24. Miró J, Huguet A, Jensen MP. Pain beliefs predict pain intensity and pain status in children: usefulness of the pediatric version of the survey of pain attitudes. Pain Medicine 2014;15(6):887-97. DOI: 10.1111/pme.12316. [ Links ]

25. Jensen MP, Adachi T, Tomé-Pires C, Lee J, Osmar Z, Miró J. Mechanisms of hypnosis: towards the development of a biopsychosocial model. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 2014;63(1):34-75. [ Links ]

FUNDING For the performance of this work, JM has received funding from the Obra Social de Caixabank, the Universitat Rovira i Virgili (PFR program), the Ministry of Science and Competitiveness. Likewise, JM's work is supported by the Catalan Institute for Research and Advanced Studies (ICREA-Acadèmia) and the Grünenthal Foundation.

Received: January 20, 2018; Accepted: April 02, 2018

texto en

texto en