Introduction

Health in prison is founded on the sole gruesome context of imprisonment and reflects the high prevalence of dysfunctions and shortcomings, in this case especially regarding mental health, that affect inmates -frequently connected to the presence of a history of addiction.

There is a high prevalence of anxious and depressive symptoms among the imprisoned population2,3. More specifically, in Spain, according to a study by the Directorate General of Penitentiary Institutions4, there is an outstanding percentage of mental disorders among the imprisoned population (17.6%), with 2.7% of inmates having a record of suicide attempts. As previously stated, this is directly linked to the high prevalence of problem drug use, (recurrent drug use that causes actual harms to the person including dependence or other problems) in this population although once inside prison such use drops, with drug use rates in prison of between 0.2% and 4.1% except for cannabis, with a use rate of 21.3%. Moreover, during imprisonment, 26% of inmates have been or are currently under some type of treatment for drug addiction5. However, there are subjective, emotional and other psychological aspects that have not been thoroughly assessed, among which we find emotional wellbeing.

Wellbeing is a broad concept difficult to achieve. It refers mainly to a set of subjective experiences - which differ from other psychic manifestations-7 which can be included within the universe so called quality of life and whose negative manifestations entail emotional consequences such as depression episodes, anxiety disorders or self-injury. In this sense, we took as personal wellbeing indicators of every female inmate the presence or absence of a history of mental illness.

How men and women face imprisonment varies greatly. Women inmates are a minority within Spanish prisons, invisible and discriminated within the system since their particularities are not considered. For example, there are still differences regarding the approach, treatment, healthcare, structure and so on between men and women8-13. Moreover, there are further problems and limitations when considering foreign female inmates (who account for 28.8% of female inmates according to the estimates by the Secretary General of Penitentiary Institutions as for March 2016). Most of them have not even lived in our country, since many were detained as drug couriers14-16.

The objective of this study is to assess emotional wellbeing among women imprisoned in Spain, by means of the evaluation of their mental health status (presence or absence of psychiatric symptoms) and identify factors affecting it. To this end, several variables of different nature have been analyzed (age, motherhood, family and social support, partners, history of addiction also known as substance use disorder-SUD and country of origin) to identify their relationship with mental health and define which play a role in the emotional wellbeing of the population under study.

Material and methods

This study is embodied in the research “Drug abuser female inmates and their social reintegration. Socio-educational study and action proposals” [Ref. EDU2009-13408]. It counts upon de the institutional endorsement and the authorization of the Ethics Committee of the Secretary General of Penitentiary Institutions, Ministry of the Interior and the Council of Justice of the Generalitat de Cataluña (only autonomous community with competences on this matter).

The study focuses on women serving second or third-degree sentences in prisons within the Spanish territory, which by the time of the study were 3484.

The sampling process was complicated since several factors needed to be taken into account:

These women were hosted in different types of facilities, both in open and enclosed regimens. According to experts, it was especially relevant to obtain information from women hosted in specific facilities such as: social integration centers (SIC) penitentiary facilities (PF), psychiatric hospitals, external mother and baby units (EMB), dependent mother and baby units (DMB) and educational treatment units (ETU). Thus, those were considered hot spots regardless the number of facilities or the number of women hosted in each one since they were considered centers “of interest”.

-

We lacked a nominal inmate list and further, this population is subject to transfers and being unavailable due to specific activities within the penitentiary routine.

The study was voluntary. Simple randomization was carried out where there was a significant number of women.

Furthermore, as in all sampling process two issues had to be considered: variability and the cost of sampling units. None could be anticipated in a situation as previously described and thus stratified sampling proportional to facilities in each autonomous community was carried out. Moreover, the aforementioned “centers of interest” were taken into account, all of this subject to budgetary restrictions. For further information please refer to Añaños-Bedriñana (2017)17. Last, approximately 17% of the population in 42 facilities underwent sampling, a figure which is perfectly appropriate for this study.

Five hundred and thirty-eight forms were filled in. However, after a thorough data cleansing process, according to the study’s main objective, we only counted upon a sub-sample of 434 women. The reason is that incomplete forms were discarded together with those with no answers for the variables under study. The final sample was still enough for the study’s objectives.

The form was specifically designed by the research team in the aforementioned project upon request. It was developed by experts in each area of questions and it underwent external assessment by other experts before a pilot test was launched prior to its definite utilization.

It is a broad tool that includes items on emotional/psychological wellbeing focused on the suffering of mental health problems. It includes three questions on a history of depression or anxiety and attempted suicide or self-injury. All these variables are qualitative dichotomous and of ended answer: yes or no. According to these answers three categories that level out the state of mind, emotional and mental state by creating a negative scale. Therefore, it reflects negative stages of wellbeing. The presentation of depression and/or anxiety symptoms is considered a mild stage of negative wellbeing. The second stage would include self-injury and last attempted suicide would be the most severe stage of women included in this study.

The research and analytical process is quantitative and derived from the form provided to the sample. More specifically estimation has been made by means of confidence intervals parallel to the difference of proportions and binary logistic regression.

The regression model is a multivariate technique that allows knowing how k>1 variables, so called explanatory variables (X) influence another variable, also known as explained variable (Y). However when the dependent or explained variable is binary or dichotomous (0/1, yes/no) and we want to predict the value of Y or establish the relationship with the rest of variables, we encounter several issues that make the use of binary logistic regression necessary (see Matilla et al., 2013)18 the logit model being one of the most used. This model uses the logistic function ranged between zero and one and shows non-linear growth with greater increases in the central part as shown in Figure 1.

The logit model can be defined as

Where α, β 1 , β 2 , β 2 , …β k are coefficients or the model’s parameter and exp the exponential function. By substituting the values of estimated parameters by non-linear least squares or maximum likelihood we will obtain the probability of Y being 1 P(Y=1).

The interpretation of coefficients is not as direct as in a regression model and we need the concept of relative risk (odds ratio OR) defined as the ratio of the probability of an event occurring to the probability of an event occurring to the probability of an event not occurring. The exponential of β 1 ,β 2 ,... β k corresponds to the relative risk and can be understood as a measure of the influence of variable Xi on the risk of an event occurring assuming that the rest of the variables remain the same. The sign of β 1 ,β 2 ,... βk indicates the direction of the effect of explanatory variables.

The calculation was obtained by means of IBM SPSS version 2.0 software. More specifically, for the logistic regression the “Enter” method was used since it is the most appropriate when trying to establish relationships between variables and it allows the researcher to keep control on the variables introduced in the model.

Results

Next, we present the frequency obtained for the different levels of negative wellbeing taken into account. 64.3% of the sample reports having suffered depression and/or anxiety symptoms. The second level (self-injury) was reported by 27.9% and last attempted suicide, the most severe stage was reported by 30% of the participants.

Socio-demographic data indicate that offences against Public Health are the most common types of offence (47.1%). 62.7% reports problem drug use while 37.3% does not. With regard to nationality, 75.8% of women in the sample are Spanish (329) while 24.2% come from Latin America (105), with almost a third being from Colombia.

By considering the aforementioned three categories of negative psychological wellbeing and prior to logistic regression, independence tests were carried out to identify what factors influenced this states, the following being ruled-out: motherhood, social or family support, gender-based violence, having or not a partner although we understand that these variables are also relevant in the matter. Therefore, the fact that these variables were ruled-out responds to the analysis itself. Likewise, the analysis has determined the consideration of the variables history of addiction and nationality for the study.

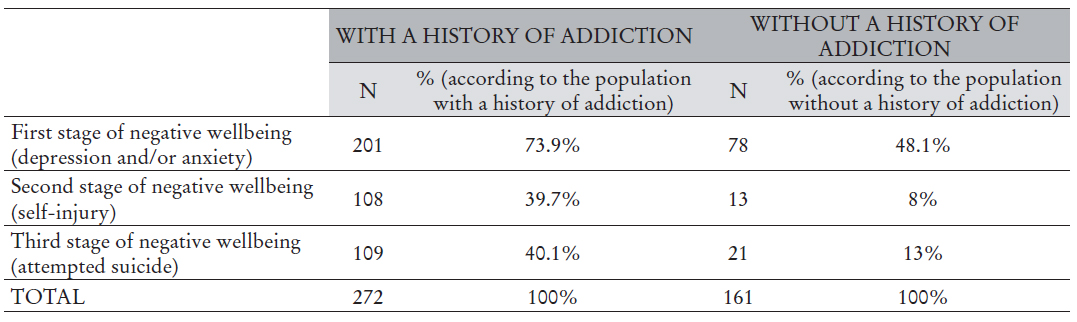

The variable that measures the presence or not of a history of addiction is significant for the three categories of negative wellbeing (chi-square test, p value< 0.001 in the three categories for a signification level of 5%; Table 1).

If we compare the sub-sample of women with and without a history of addiction and taking into account the confidence intervals of the difference of proportions, we can conclude that emotional wellbeing is lower in the first group since confidence intervals are negative for all categories. The presence of depression and/or anxiety symptoms as well as self-injury and attempted suicide is most frequently found in women with a history of problem drug use (Table 2).

Table 2 95% confidence intervals for the ratio difference of women in negative wellbeing categories according to history of addiction.

Another significant variable is nationality (chis-quare test, p value < 0.001 in the three categories for a signification level of 5%; in the three categories). When considering the sub-samples (Spanish and Latin American), 36.2% Latin-American inmates report depression and/or anxiety symptoms while 75.3% of Spanish inmates did so. Likewise, self-injury is present in 9.5% of Latin-American inmates and 33.8% of Spanish inmates. Attempted suicide has been carried out by 8.6% of Latin-American inmates and 36.9% of Spanish inmates. Moreover, 95% confidence intervals have been calculated for the difference of proportions in each category between the two sub-samples. The difference of proportions ranges between 27 and 47% for the first category, between 14% and 34% for the second and between 18 and 38% for the third, which supports the fact that Spanish women have less emotional wellbeing in all three stages.

A relevant fact is that women from Latin America present a low percentage of addictive behaviors (20% report problem drug use) in comparison with Spanish women (76.3%). In both cases, the presence of problem drug use entails a trend towards negative wellbeing.

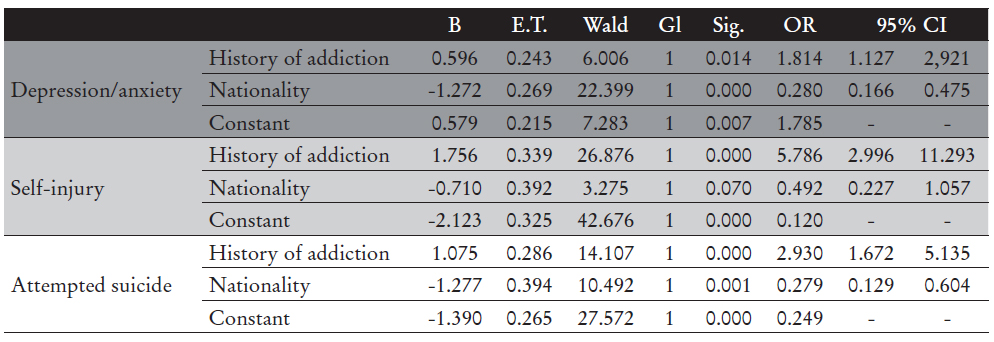

In order to confirm that the variables nationality and history of addiction plates a role in the degree of emotional wellbeing and in view of the dichotomous nature of both (presence or not of depression and/or anxiety symptoms, self-injury, attempted suicide), binary logistic regression was used. Nationality (Latin-America vs Spain) and history of addiction (No vs Yes) have proven significant for all three categories (see Table 3). The control category was defined as being Spanish without a history of addiction.

Next, we will provide three measures that allow comprehensive assessment of the validity of the results of the estimation. (Table 4) The first (-2LL) is based on the likelihood logarithm (the smaller the better adjustment) and the others are coefficients of determination similar to those of a regression model: Cox-Snell R-squared and Nagelkerke R-squared, which express the decimal fraction of the variation explained by the model. They are frequently lower in comparison with the r-squared of a regression model, the best of which is the self-injury category with a variation of 19%.

Table 4 Summary of binary logistic regression for the models considered.

| Summary model | -2 LL | Cox-Snell R-squared | Nagelkerke R-squared |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression/anxiety | 511.052 | 0.114 | 0.157 |

| Self-injury | 451.412 | 0.133 | 0.191 |

| Attempted suicide | 477.793 | 0.112 | 0.159 |

We also include the results of the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, which contrasts the validity of the model (Table 5). In this case, the ideal is to accept what indicates that the model is appropriate (given by higher significance). Under no circumstances, is the null hypothesis rejected and therefore the models are considered suitable.

Table 5 Hosmer-Lemeshaw test for the models considered.

| Hosmer-Lemoeshow test | Chi-square | Gl | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression/anxiety | 0.328 | 2 | 0.849 |

| Self-injury | 1.136 | 2 | 0.567 |

| Attempted suicide | 0.190 | 2 | 0.909 |

We can state that in view of the aforementioned results, the models are suitable to establish the direction and value of the relationship of the variables included. Therefore, a history of addiction influences wellbeing (as depicted in Table 3 for a significance level of 5%). For the presence of depression and/or anxiety symptoms, there is a 1.8 fold increase in the probability of suffering these if there is a history of problem drug use. Being from Latin America seems a protective factor against negative levels of wellbeing: there is 72% less probability of suffering from anxiety or depression among female inmates from Latin America than from Spain. With regard to self-injury, a history of addiction entails a 5.7 increase in their probability while being from Latin America reduces their risk by 51%. Likewise, it is 2.9 times more probable to attempt suicide in the presence of a history of addiction and there is 73% less probability of these behaviors among Latin-Americans.

Discussion and conclusions

The presence of a negative wellbeing amongst our participants is high as shown by the available data. The prevalence of mental disorders among imprisoned women in surprisingly high in comparison with imprisoned men and with the Spanish general population. More specifically, the study by Staton, Leukefeld and Webster19 shows that the higher percentages of depression and anxiety are found among women with prevalence rates of 62% and 53% correspondingly - data very much alike that concluded in our study. This can be explained, as stated by Altamirano7, because of a high exposure to traumatic events, substance abuse and alcohol addiction and mental health issues among the imprisoned population.

Two factors were found to be the main determinants of the mental health condition of the participants in this study: a history of addiction and their nationality. The link between problem drug use and mental health has been assessed throughout the extensive amount of literature on the matter. Therefore, Periago 20 states, “depression, anxiety and other mental disorders are associated with alcohol and other substance dependency. This dependency -which is a mental health problem itself- is a relevant risk factor for other mental health disorders. Likewise, mental disorders favor the development of alcoholism and drug abuse” (p. 223). More specifically, there are studies relating the use of these substances with suicide21.

In this regard, several studies carried out in correctional facilities have outlines the high percentage of individuals with addiction disorders hosted within22,23. In Spain, data from the State Survey on health and drug use among the imprisoned population -ESDIP-22 concluded that only a small proportion initiates drug use in prison and thus, most have initiated drug abuse before being convicted.

In a research with female inmates in a correctional facility in Spain16, the high prevalence of psychopathological disorders is outlined. In summary. 32.3% of the sample presented depression issues and 63.1% of them belonged to the drug use group. With regard to anxiety problems, they found similar results: 59.3% presented anxiety symptoms, out of which 65.7% were drug users. This data supports the fact that a history of problem drug use is a risk factor for emotional wellbeing in prison.

The country of origin was another significant variable affecting emotional wellbeing in two ways. On one hand, it exerts a direct cultural influence and on the other, culture affects the degree of satisfaction in life. Individualist cultures emphasize the freedom of choice and the needs of individuals while collective cultures are into rights, the needs of the other and the acceptance of one’s fate. Therefore, freedom is a strong predictor of satisfaction for individualistic societies24. The data we count upon with regard to the country of origin and wellbeing differ greatly with the geographical place, the type of society and the particular collective. In the general population of Latin America 5% of adults suffer from depression25, while in Spain some authors point out that between 28% and 40% do so26,28 although official statistics report that depression/anxiety is present in 14.6% of the population26. This helps us understand out results.

All these data and views support and explain that a Latin-American origin acts as a protective factor against negative wellbeing. Especially if we consider that these women were detained and convicted in Spain, but most of them have not lived in this country, but acted as drug couriers14-16. Another revealing result is that of Villagrá et al. (16 who underlines the low prevalence of drug use among women from Latin America. This is evident in our study, with a prevalence of 20% against 76.3%. In both sub-groups, women with this kind of problem at are a higher risk of negative wellbeing.

In summary, this study concludes that the presence of a history of addiction and the country of origin (birthplace) of women hosted within the Spanish correctional system are determinant variables for their personal and emotional wellbeing. On the other hand, other variables were not found significant (motherhood, social or family support, gender-based violence, presence or absence or partner). Therefore, addiction behaviors are endorsed as a risk factor for negative emotional wellbeing and a Latin-American origin is confirmed as a protective factor in this study.