Introduction

The number of inmates suffering from mental illnesses in Spanish prisons is remarkably high. Such diseases are often linked to substance use disorders (mainly alcohol and drugs, especially cannabis), and levels of comorbidity are up to six times greater than in the general population1.

Research has shown that the prevalence of mental disorders in prisons is higher than it is in the general population2. Psychotic disorders, severe depression and antisocial personality disorders are four, six and ten times more common amongst inmates than in the Spanish population3.

This over-representation of inmates with mental health problems is not common to Spain alone; other countries such as Italy, Germany and Norway have also carried out studies to gain a clearer idea of the situation in their prisons, and each one has reached the conclusion that there is an excessively large number of inmates with mental disorders3. Prisons in the UK have highlighted a significant general prevalence of psychiatric disorders that is higher among female inmates than men, although this general difference between both groups is not so evident in each specific disorders4.

In particular, the PreCa study5 (on the prevalence of mental disorders in prisons) carried out in Spain estimates that the prevalence of any kind of mental disorder amongst Spanish prisoners at some point in their life is approximately 84.4%, while it fluctuates at around 41.2% in the previous month. The most common disorders include anxiety, SUD, and emotional and psychotic disorders.

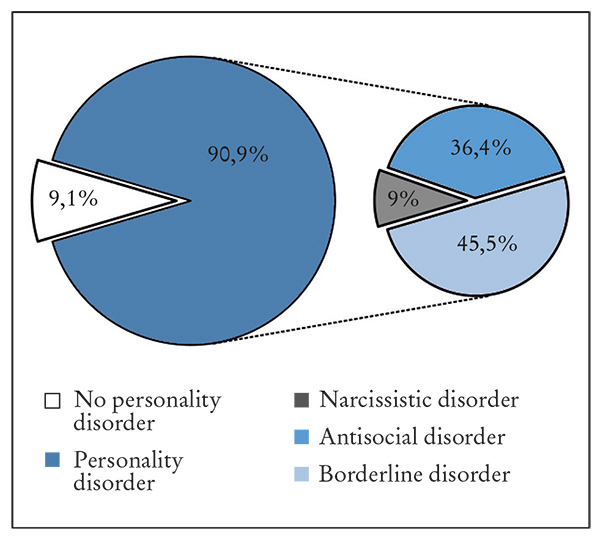

There has also been a progressive increase in the number of inmates with personality disorders in Spanish prisons, where, out of the total number of inmates, 80% suffer from some kind of personality disorder (Figure 1). Cluster B disorders are the most common, (borderline, antisocial and narcissistic), while paranoid personality disorders are the most common one to be find in cluster A5.

Figure 1. Prevalence of personality disorders in Spanish prisons according to the PreCa study (Prevalence of mental disorders in spanish prisons).

The risk factors that often figure in the sociodemographic profile of inmates when calculating the likelihood of mental disorders in prison are linked to age (higher between 20 and 29 years), marital status (higher amongst singles), level of education (more common when there is low educational attainment) and job situation (higher amongst the unemployed)5. Furthermore, many inmates often present life histories full of adversities, difficulties and trauma, in marginalised and hostile surroundings, with a high degree of abuse, mistreatment and abandonment in childhood6.

Imprisonment for any inmate involves a process of adaptation to prison life characterised by routine, lack of privacy, affective isolation, repeated frustration, constant vigilance and a new scale of values that makes the relational climate between inmates an unstable one, characterised by mistrust and aggression7. All this creates an emotional overload that makes adaptation, social adjustment, healthy interpersonal relationships and appropriate habituation to the prison environment very difficult.

Adaptation to prison life takes place gradually over the course of the stay in the centre and consists of a process called “prisonisation”7. When an inmate makes first contact with a total institution such as prison, he or she shows regressive, immature, anxious and unstable behaviour, in response to entry into what is a highly regulated environment with a set of routines. If the inmate cannot adapt to the prison environment, a failure of adaptation comes about that is expressed in the form of real behavioural disorders such as anxiety, affective problems, depression and even aggressive behaviour towards themselves (auto-aggressive) and others (hetero-aggressive). Finally, when adaptation is impossible, a serious mental illness may develop, which takes the form of affective disorders, psychotic breaks, severe anxiety attacks, etc., bringing about a complete lack of adaptation to the prison environment7.

There also exists a phenomenon in the prisonisation process and throughout imprisonment in which levels of neuroticism among inmates increase greatly, leading to greater emotional instability, lower tolerance to stress, and strong emotional reactions, which can further worsen adaptation to the surroundings and relationships, not only with other inmates but also with prison staff8.

Although it is difficult to find information in the scientific literature about the potential influence of the many individual and environmental factors on an inmate's prisonisation, the fact is that any kind of pathology or dysfunction that they might present, or even suffer from, before entering prison, will progressively aggravate their incapacity to adapt, which in turn will act as an obstacle to correctly maintaining the environmental equilibrium in a prison7.

The objectives of this study are as follows: review the influence of inmates with mental disorders on the relational climate in prisons, and identify the interventions proposed in Spanish prisons to improve the relational climates inside their facilities, bearing in mind the large number of inmates with mental disorders.

Material and method

A review of the literature was carried out, using the Scopus, Pubmed and Medline (Figura 2) databases, to review articles and reviews of the previous 15 years that answer the question as to whether and how the overrepresentation of inmates with mental problems affects the environmental and relational climate of prisons, and then identify what is being done in Spain to mitigate problems in the prison social climate caused by the large number of inmates with mental illnesses in prisons.

Other sources were used, such as the online bibliographical indexes of the Spanish Ministry of the Interior, about the prevalence of mental disorders in prisons and the resulting links to recidivism, which made it possible to provide a more detailed picture about the over-representation of mental disorders in prisons and their impact on the social environment there3.

The following terms were used for the bibliographical search: mental disorder (or) personality disorder (or) mentally ill (or) sick convict (or) forensic patient (and) social climate (or) interpersonal relation (or) environment (or) relations (or) coexistence (and) prison (or) jail (or) penitentiary centre (or) deprivation of freedom (or) seclusion (or) prison penalty.

The studies used reviewed, evaluated and/or described how the presence of a large number of persons with mental disorders affected the relational climate of prisons. Articles and/or reviews in Spanish and English that focused exclusively on convicted adult inmates were included, omitting any articles that studied young offenders' centres. For the first objective, the search was not limited solely to Spanish prisons due to the lack of scientific literature on the subject.

Only articles and/or reviews that were completed, reviewed and published by peers were included. Another limitation imposed was that the articles and/or reviews should belong to the mental health subject area. The bibliographical search was also limited to interventions that took place specifically in the Spanish prison setting.

RESULTS

There is little in the way of scientific literature in the available bibliography on the relational climate of prisons and interventions. However, it is true that there has been a progressive increase in recent years in the number of studies in response to the current overcrowding in prisons and the increasing numbers of inmates with mental disorders (Figure 3).

The literature available on this subject, while scarce, does respond to a current reality in prisons, and so it can be used to describe the climate in Spanish prisons with regard to mental illness and the interventions used to deal with it (Table 1).

Table 1. Articles selected for systematic review.

| Article | Authors | Journal | Sample | Summary of conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changes in attitudes to Personality disorder on a DSPD unit (2005). | Bowers L, Carr-Walker P, Paton J, Nikjam H, Callaghan P, Allan T, et al. | Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. | 66 prison officers. | Prisons should invest in trained and qualified staff who possess a positive attitude and are receptive to learning, to ensure that their attitude with regard to inmates with personality disorders is as suitable to their needs as possible. |

| Los trastornos de personalidad en reclusos como factor de distorsión del clima social de la prisión (2009). | Arroyo JM, Ortega E. | Revista Española de Sanidad Penitenciaria. | 60 males in mates. | There is a significant relationship between imbalances in the prison social climate and the existence of personality disorders, caused mainly be aggressive interpersonal behaviour and compulsive demand for drugs. |

| Characteristics of Male Criminal Offenerd: Personality, Psychopathological, and Behavioral Correlates (2009). | Edens JF. | Psychological Assesment. | 1,062 males in mates. | An interpersonal style characterised by low affiliation and high dominance with the presence of antisocial behaviours, generating behavioural imbalances and dysfunctions that lead to institutional misconduct. |

| The prevalence of mental disorders in Spanish prisons (2011). | Vicens E, Tort V, Dueñas RM, Muro A, Pérez-Arnau F, Arroyo JM, et al. | Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. | 707 males in mates. | The prevalence of mental disorders in Spanish prisons is high. The fact that almost all inmates present a high prevalence of at least one mental disorder implies that there is a need to improve psychology services. |

| Estrategias asistenciales de los problemas de salud mental en el medio penitenciario, el caso español en el contexto europeo (2011). | Arroyo JM. | Revista Española de Sanidad Penitenciaria. | - | Bibliographical review of healthcare policies of administrations regarding mental health problems in prisons. Little scientific literature is available. There is a need for coordination between administrations and a therapeutic response should be offered to inmates that is comparable to the services offered to the general public. |

| Orange Is Still Pink: Mental Illness, Gender Roles, and Physical Victimization in Prisons (2015). | Schnittker J, Bacak V. | Society and Mental Health. | 18,185 male and female inmates. | Mental disorders are more closely linked to victimisation amongst male than female inmates. However, the size of the gender difference varies greatly according to the specific disorder. Depressive disordersare more closely linked to victimisation of men, while psychosis shows no gender difference. |

| Mental health of prisoners: prevalence, adverse outcomes and interventions (2016). | Fazel S, Hayes AJ, Bartellas K, Clerici M, Trestman R. | The Lancet Psychiatry. | - | The prevalence of mental disorders in prisons is higher than in the general population. However, interventions are few andof low quality in comparison to outside prison. There is a need for policies that can improve existing interventions. |

Source: compiled by author (2020).

According to Robinson et al.9, the social climate is a multifactor construct that describes the setting of a given scenario, in this case that of a prison, which has an influence on the mood and behaviours of the persons that live there. It therefore enables the interpersonal relationships with prison staff and with other inmates to be described.

Clark10 states that according to the collective perception of the prison social climate, there will be a greater or lesser likelihood of violence, aggression and institutional misbehaviour. Consequently, perceptions such as a low feeling of safety, poor group cohesion or facilities with high security levels, will lead to a prison atmosphere where there is a greater tendency towards violence and aggression that therefore generates a larger number of offences that need to be penalised. Furthermore, the presence of a large number of inmates who present mental health problems with pathological behaviour patterns will have a dysfunctional effect on the social climate of prisons, due to the difficulties in adapting to the environment, emotional and/or cognitive instability, difficulties in coping with stress and frustration, etc., thus generating a climate full of tension and negativity, both for the inmates themselves and for the other people with whom they interact.

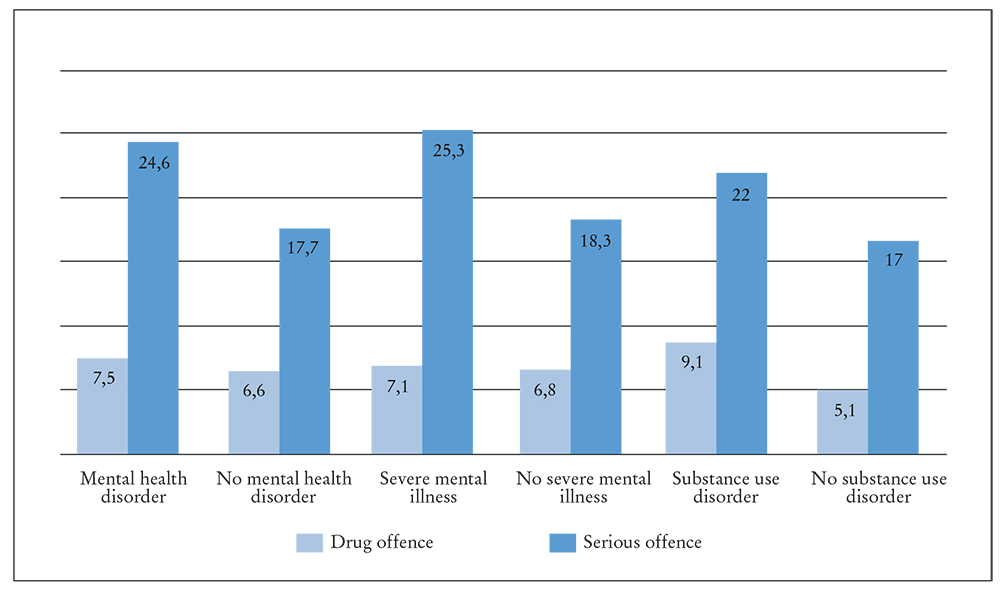

According to Henry11, the existence of dysfunctional behaviours as a response to difficulties in social adjustment to the prison setting leads to breaches of prison regulations, which take mainly take two forms: drug offences, consisting of possession, trafficking and consumption; and serious offences, such as verbal and/or physical aggression against other inmates or the other persons with whom they interact, possession of arms, attempts to escape, etc.

Henry11 reached the conclusion that inmates with mental health issues and drug disorders run a higher risk of breaking prison rules, with a particular risk of committing serious offences related to inadequate interactions with the prison social climate (Figure 4). This risk is even greater amongst inmates who suffer from an acute mental illness and adverse life experiences such as recidivism.

Offences committed in prison involve the application of penalties. This was the variable used by Arroyo and Ortega7 in a study of Spanish prison, where they observed the relationship between disciplinary measures for aggressive behaviour and inappropriate interpersonal reactions and the presence or absence of personality disorders. Their conclusion was that the inmates most likely to be penalised were inmates who suffered from borderline personality disorders, influenced by unstable emotions, impulsive and reckless behaviours, which led to negative social interactions and a greater risk of committing offences and aggression towards others during imprisonment12, followed by inmates with antisocial and narcissistic disorders (Figure 5).

Arroyo and Ortega7 state that in general terms inmates with mental illnesses, in particular those with personality disorders, often tend to be one of the focal points of difficulties in interpersonal relationships in prison, especially when they have major difficulties in behaving in accordance with the interpersonal social rules and codes established in prisons.

Clark10 also mentions the potential negative influence of mental illness when penalties are applied, since it is more likely for a mentally ill inmate to be punished by being separated from the group. Disproportionate penalties such as solitary confinement are more common, thus worsening the inmate's capacity to adapt, and damaging the relational style used in interactions with others. Such excessive measure are mostly an outcome of prisoners with mental health problems being perceived as excessively dangerous, both to themselves and to other inmates and prison staff10.

Despite the very large number of inmates with mental health issues, Arnau et al.13 consider that the interventions used to mitigate problems in the prison social climate and interactions caused by an excessive number of such cases are insufficient.

As regards interventions of a national scope, Arroyo-Cobo6 state that there is little in the way of scientific literature that discusses healthcare policies for the mental health problems currently inundating Spanish prisons. He also concludes that the main programme in Spain is the Comprehensive Care Programme for the Mentally Ill (Programa de Atención Integral a Enfermos Mentales (PAIEM)), the objective of which is to build personalised treatment and rehabilitation programmes6.

In view of all this evidence, Clark10 restates that instead of finding a prison social climate with inmates who do not suffer from mental illness and who also possess balanced personalities, what is found are inmates suffering from mental illnesses, the possibility of adapting to and overcoming the environmental and individual adversities implicit in entering prison is reduced, and pathological relationships are created both with oneself and with the other members of the environment.

How mental health influences the relational climate of prisons is a question that can be answered by observing breaches of the regulations that mainly affect interpersonal and/or intrapersonal relationships, the penalties and even the victimisation undergone by mentally ill inmates. According to Arroyo and Ortega7, in a total institution such as a prison, prisoners' day to day lives and their relationships are subject to control by the prison, which leads to behaviour being regulated through rules that, once broken, lead to punishments that can also have a detrimental effect on this type of inmate, and so worsen the prison relational climate.

Discussion

In an enclosed relational environment such as a prison, where the predominant factors are restrictions, absence of freedom, lack of privacy, control, routine and forced coexistence amongst inmates, relationships with oneself and with others are often the main source of tension that can break the equilibrium of such a setting.

Being in prison obliges an inmate to make constant adjustments to the surroundings, where his or her capacity for psychosocial adaptation are continuously put to the test. Identifying the “code” of prison is the foundation for understanding social relationships within such a setting, and if this is not understood, it becomes the first in a line of obstacles that stop an inmate from becoming accustomed to prison life7.

Thus, the difficulties of adaptation that mentally ill inmates present before imprisonment or develop over the course of prisonisation can cause behavioural maladjustments that can turn them into both victims and perpetrators of prison offences, distorting identification of the prison code and so worsening the relational climate14.

The relationship between victimisation and mental disorder in prison can be explained mainly by stigma and provocation. Stigma leads to mentally ill inmates becoming victims in prison. The fact that they suffer from a mental illness means that others view them as a sign of weakness and/or a source of potential misconduct that breaks prison rules; while provocation focuses more on the nature of the symptoms and not on how they are interpreted by others. Since not all disorders necessarily lead to provocative behaviour, the situation depends more on the specific type of disorder, and victimisation is more common amongst inmates with personality disorders and acute mental disorders such as psychosis, since they involve behaviours of this nature and difficulties in adaptation and self-control in accordance with the established social rules14.

Stigma, dysfunctional styles of social interaction and the resulting victimisation make healthy interpersonal relationships a difficult process. Furthermore, inmates with mental disorders who are victimised show a higher risk of presenting self-destructive behaviours, which worsen the prison social climate further still15.

The maladjustment in the prison environment is also related to pathological, aggressive and/or violent interpersonal relationships that generate misconduct and breaches of the “code of prison behaviour”. An interpersonal style characterised by high dominance and low affiliation as antisocial traits is associated with conduct that leads to maladjustments and dysfunctions in relationships between prisoners16.

There are also high levels of aggression and violence in the prison environment caused by inmates who mainly suffer from acute mental disorders, SUD and group B personality disorders17. This factor leads to rule breaking which in turn aggravates imbalances in the prison relational climate.

Despite the over-representation of inmates with mental disorders in prisons and the resulting consequences, the quantity and quality of existing interventions are less than those available outside prison facilities18.

The large number of inmates who suffer from mental health problems makes it necessary to promote a change of attitude by staff towards this type of inmate, through adequate classification, a positive attitude and appropriate treatments and interventions that can help to mitigate the consequences of the overrepresentation of inmates with mental disorders19.

Finally, some studies show that treatments available to mentally ill inmates can lead to a higher likelihood of victimisation, either because of the perceived privilege of receiving them or because of the severity of the disorder itself20, which in turn maintain pathological interactions and maladjustments in the relational prison climate.

Conclusions

One of the realities of the current situation in prisons is the large number of inmates with mental illness and an unstoppable increase in the number of such inmates when compared to the general population.

This over-representation of inmates with mental disorders has serious consequences, such as the worsening of the prison social climate and pathological interpersonal relationships, not only because of the symptoms of the disorders, but also because of the stigmatisation linked to them.

It is necessary therefore to use prison resources to create mental health interventions and treatments of sufficient quantity and quality that can help inmates to adapt to the prison setting, improve the prison relational climate, reduce dysfunctional behaviour that leads to misconduct and infringements of prison regulations, and adapt disciplinary measures to the inmates' condition and behaviour.

Taken together, these measures would have a positive impact, not only on the day to day life of the prison and its relational climate, but also on the future social interactions of inmates once they are released.

The limitations of this study derive principally from that fact that there is little in the way of literature on studies and interventions on this group of inmates, which continues to grow, and from the lack of action taken on the potential consequences, not only in prisons but also in the public domain. There is also a shortage of longitudinal studies that enable the objectives of prisonisation to be clearly observed, or on the interpersonal and intrapersonal styles adopted by mentally ill inmates that have such a large impact on the prison environment.

Future lines of study should therefore focus on creating longitudinal studies that take into account the prisonisation process and its impact on the inmate in particular and on the prison as a whole. It is also vitally necessary for administrations to collaborate in adequately managing resources to enable personalised programmes to be created that can prevent the potential consequences of prisonisation, and treat and rehabilitate inmates who suffered from mental illness before being sentenced or who have developed a mental disorder as a result of failures in adapting to the prison setting.