Non-suicidal self-harming is defined as a self-inflicted act that causes pain or superficial injury but without the intention of causing death. The aims of self-harming generally include: to reduce situations of tension; diminish negative feelings; as a way to solve personal problems; a call for attention; to get something and even as a self-imposed punishment1.

Non-suicidal self-harming is highly prevalent in prisons. One of the most common types of self-injury is cutting the skin, known in Spanish prison slang as "chinazos", which some authors consider to be manifestations of the prison subculture2.

Other kinds of non-suicidal self-harming include cigarette burns; hitting a part of the body (head, fists); swallowing foreign objects (springs, razor, batteries, etc.); sewing the lips; all of which have been mentioned in the literature3,4.

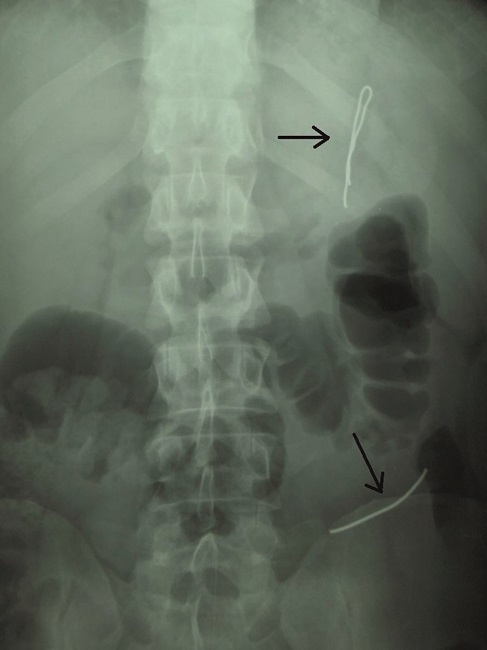

A classic form of self-harming is the use of "missiles", as they are called in prison slang, referring to the introduction via a perforation in the skin of a metal object, particularly in the subcutaneous tissue of the abdominal wall, without puncturing the internal organs. The most commonly used objects are nails, needles and wires5.

The procedure for this type of self-injury was usually to take the inmate to hospital for X-rays and extraction of the object. Figure 1 shows an X-ray of an inmate who had committed self-injury with two pieces of wire, which can be seen in the form of two metal fragments in the abdominal zone.

Figure 2 shows the self-injury of another inmate, consisting of three sewing needles inserted in the abdominal area in a crown to rump direction, with the same angle of inclination. These locations tend to be the most common ones.

Another, less common and highly intriguing location can be seen in Figure 3. This case consists of the introduction of a sewing needles in the popliteal fossa of the inmate’s right knee. The image is so clear that the eye of the needle can be seen. Evidently, surgical intervention was required to remove the object.

In most cases, if the "missiles" were not inserted in difficult areas or presented symptoms that required hospital admission, and if the object could be located by touch, health professionals would use a small incision to extract it in the prison nursing bays.

Since most of the objects were not hard to extract, and the process to remove them could take place in an outpatient setting within the prison itself, this type of self-injury was committed with decreasing frequency.

This type of self-harming is now a thing of the past, given that it is rarely seen in current clinical practice.