Introduction

Tuberculosis continues to be one of the infectious diseases with the highest levels of morbimortality in the world and is a major cause of mortality in developing countries1.

According to data published by the Spanish National Centre of Epidemiology of the Carlos III Health Institute, a total of 3,384 cases of tuberculosis were reported in Spain. 2,503 of these cases were persons with pulmonary tuberculosis (68%), while 1,098 were extrapulmonary cases (30%), of which 36 were forms of meningeal TB. 63% of the total number of cases were men, giving a ratio of 1.7 for men/women. The mean age was 48 and 42 years, respectively.

In 2020, 34.4% (1,268) of the declared cases of tuberculosis were born in a country outside Spain. In the same year, mortality was 0.56 per 100,000. The rates of incidence for tuberculosis in Spain followed a downward trend in 2015-2020, although this reduction may have been caused by the effects of the pandemic; partly because of the efforts made to mitigate it and as a result of delays and fewer diagnoses2.

Spain is a country with one of the highest prevalences of TB in Europe. In recent years demographic changes have taken place in the Spanish population that indicate that there is a higher proportion of patients diagnosed with TB and LTBI in autonomous communities with a large number of immigrants3.

The prevalence of LTBI amongst prison inmates is estimated to stand at 40-50% and in global terms it is believed to two or three times higher than the estimated figure for the Spanish population4.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) adopted the global “end TB” strategy in 2014 with a view to intensifying the efforts to eliminate TB worldwide. To make this proposal a reality, the WHO set a milestone of reducing levels by 90% in 2035, using the 2015 levels as the baseline. The first two targets of the TB control and prevention plan were met in 20205.

The first target was a reduction of 15-21% in the global level by 2020 in comparison to the figures in 2015. The actual reduction was 26.5%. The second target was a mean annual reduction in the rate of pulmonary TB of 4% for the 2015-2020 period. Two of the targets established by the WHO6 for total levels and pulmonary localisation by 2020 were therefore achieved. However, the target set for 2035 cannot be met if the same rate of reduction continues. To do so, the rate would need to be kept at an average annual reduction of 9.5%, a figure higher than the actual one for 2015-2020, which was only 6%. This means that the current rate of reduction is insufficient to meet the objectives set by the WHO6.

TT is a purified protein derivative taken from filtered cultures of human Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MT). The most widely used one is tuberculin RT-23 stabilised with Tween®-80. Two units of this tuberculin are equivalent to five units of PT-S, i.e., the standard batch adopted by the WHO as an international standard7.

The diagnosis of LTBI with TT uses techniques that study an individual’s sensitivity to different MT antigens8. The technique consists of intradermal inoculation of a purified protein derivative (TT), which contains a mixture of more than 200 antigens present in MT, in the vaccine strain, BCG and in environmental mycobacteria. The main defect lies in the cross reactivity, the effect of which is a low specificity in individuals vaccinated with BCG and in those infected by atypical mycobacteria, while the tests based on interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) are more specific when using specific MT antigens. The main virtue of the IGRA lies in the antigens used to stimulate the T cells: the protein -kD Early-Secreted Antigenic Target (ESAT-6) protein and the 10-kD Culture Filtrate Protein (CFP-10), codified in difference region 11,8.

These specific MT antigens are not present in the BCG vaccine bacilli or in most environmental mycobacteria9. In other words, the capacity of the TT and IGRA to predict the development of TB is very poor, as many individuals with positive TT or IGRA results do not go onto develop a tuberculosis infection8,10,11. However, even with this limitation, IGRAs have significantly improved the diagnosis of a TB infection7,8,10.

Although they present similar predictive values, their higher specificity has led to a reduction in the number of unnecessary preventive treatments without increasing the risk of developing subsequent active TB7. IGRAs have also improved the detection of TB infection in immunocompromised patients8,10,11. A recently published meta-analysis on the sensitivity of IGRAs showed a sensitivity of 88.24% (78.20-94.01) for the TT PT 5 mm compared to 89.66 (78.83-95.28) with the IGRA QFT. However, specificity stood at 93.31% (90.22-95.48) at the cut-off point of the TT 15 mm and rose up to 99.15% (79.66-99.97) for the IGRA12.

Materials and methods

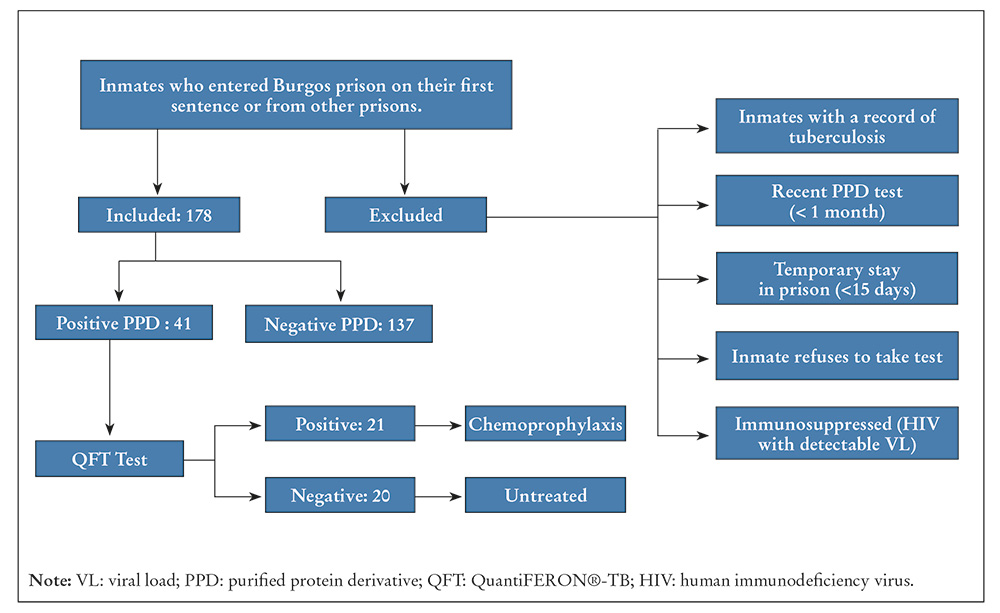

Transversal descriptive study carried out between December 2020 and December 2021 at Burgos prison, with a population of approximately 300 inmates. All the new inmates entering the module were includes and the study took place after the lockdown caused by the 2019 COVID pandemic. A TT was carried out on the subjects, the criteria for doing so being: having no background of TB and not having previously received a TT with a negative result.

The procedure for the TT by means of an intradermal reaction test consisted of subcutaneously applying two units of TT at 0.1 ml. The reading was interpreted by trained nurses and experts, who classified the results as TT+ and TT-, using different sizes of induration after the reading at 48-72 hours. Inmates with a TT result equal to or more than 10 mm were included.

The study formed part of research into contacts that are habitually carried out at Spanish prisons, in line with the recommendations established in TB control and prevention programmes in the prison setting7) and the WHO TB control programme in prisons1,11.

A TT result that was initially negative was repeated after two weeks. When a positive TT result was confirmed by the nursing staff, an appointment was made for a medical consultation, where the patient’s risk factors and background were discussed, in accordance with the guidelines for managing TB in prisons. Information was gathered from each inmate about their age, sex, background of BCG vaccination and country of origin. Procedures were followed to carry out chest X-rays and referrals were carried out with the department of microbiology to take blood samples on the same day for the QFT-TB Gold (QFT-G) test.

Interferon gamma ≥0.35 U/mL positivity was defined (after subtracting the null control) along with the open-ended result caused by a poor mitogen response (<0.5 UI/mL in positive control) or high response in null control (>0.8 UI/mL). The open-ended IGRAs were repeated and the positive or negative result was included according to the final result.

The blood samples were taken at the microbiology department of Burgos University Hospital.

An application for authorisation to gather data was issued in accordance with Instruction 12/2019 on Research in the Prison Setting of the General Sub-Directorate of Institutional Relations and Territorial Coordination.

Every inmate was informed about the study that they were participating in, and each physician asked for an authorised consent, which was recorded in the clinical history of the electronic medical office program for prisons. Patients were always visited by the same physician. The sociodemographic information was obtained from a direct interview with the inmate and was confirmed by comparing it with the data in the digital clinical history.

Participants

The participants were inmates of Burgos prison who were incarcerated for the first time or transferred from other prisons, whose TT result was positive (according to the criteria of this study), and who accepted the QFT after being informed of the LTBI detection protocol.

Sample size

The size of the sample was obtained in line with the number of inmates entering the prison as transfers from other centres or as first-time inmates. The total number of new inmates who underwent TT was 178. They all met the requirements for carrying out the test. 41 of these inmates met the criteria for positivity (more than 10 mm), and sequentially underwent the QFT test for confirmation.

Variables

The variables were: age, origin/background, numerical value of induration and the background of vaccination with BCG.

Types of variables

The two quantitative variables were: age and the TT induration value. The qualitative variables were: origin and background of vaccination with BCG.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was carried out of the all the inmates who underwent a TT and whose positive result was confirmed by a QFT. The variables analysis was carried out with the Statistical Package for The Social Sciences (SPSS) v. 25.0.

The age variable followed a normal distribution with an average of 44.58 (Kolmogorov-Smirnov) and had a standard deviation of the sample of 11.14. The TT induration value had an abnormal distribution, with an average of 15 mm, the interquartile ranges were used. The absolute values and percentages were used for the qualitative variables, while a bivariant analysis was carried out with crosstabs.

Results

A total of 178 TT were carried out and 41 inmates who met the selection criteria were evaluated (Figure 1). They were all men of over 21 years of age. The mean age was 44 years. 56% were of Spanish nationality, and most of them fell within the age range of 40-49 years. A total of 41 TT positive results were obtained, with an average of 15 mm (standard deviation of the sample: 5.29). Of the 41 TT positive cases, only 21 were positive when they underwent the QFT (an open-ended result that was positive when the test was subsequently repeated). 36% had a positive TT between 10-14 mm, and 31% had between 15-19 mm (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic variables

| Age ranges of inmates in the study | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 20-29 | 5 | 12.2% |

| 30-39 | 8 | 19.5% |

| 40-49 | 13 | 31.7% |

| 50-59 | 11 | 26.8% |

| More than 60 | 4 | 9.8% |

| Total | 41 | 100.0% |

| Origin of inmates | Frequency | Percentage |

| Spanish | 23 | 56.1% |

| Other country | 18 | 43.9% |

| Total | 41 | 100.0% |

| TT diameter in millimetres | Frequency | Percentage |

| 10-14 mm | 15 | 36.6 % |

| 15-19 mm | 13 | 31.7% |

| 20-24 mm | 10 | 24.4% |

| 25-29 mm | 2 | 4.9% |

| More than 30 mm | 1 | 2.4% |

| Total | 41 | 100.0% |

| QFT result | Frequency | Percentage |

| Positive | 21 | 51.2% |

| Negative | 20 | 48.8% |

| Total | 41 | 100.0% |

Note. Tuberculin test; QFT: QuantiFERON®-TB.

The results of the QFT showed that in the inmates with positive TT (Table 2), a larger number of inmates was observed (36.6%), the TT result of which stood between 10-14 mm. It was also found that a larger number of negative QFTs (55%) were observed in this range of TT diameters. A larger number of positive QFT results was observed when the TT was between 15-19 mm and 20-24 mm, both diameter ranges with 33.3% of the positive QFT result, respectively (chi squared [χ2] = 7.92, p = 0.094).

Table 2. Contingency table between TT+/QFT+

| Result of QFT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | Total | |||

| TT+ | 10-14 mm | Count | 11 | 4 | 15 |

| % | 55.0% | 19.0% | 36.6% | ||

| 15-19 mm | Count | 6 | 7 | 13 | |

| % | 30.0% | 33.3% | 31.7% | ||

| 20-24 mm | Count | 3 | 7 | 10 | |

| % | 15.0% | 33.3% | 24.4% | ||

| 25-29 mm | Count | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| % | 0.0% | 9.5% | 4.9% | ||

| More than 30 mm | Count | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| % | 0.0% | 4.8% | 2.4% | ||

| Total | Count | 20 | 21 | 41 | |

| % | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

Of the 21 inmates whose TT results were confirmed with the QFT, 52.4% (11 inmates) were Spanish, while 10 were foreigners and represented 47.6% of the sample (χ2 = 0.24, p = 0.62) (Table 3).

Table 3. Contingency table of country of origin/result of QuantiFERON®

| Result of QuantiFERON® | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | Total | |||

| Place of origin: Spain/abroad | Spain | Count | 12 | 11 | 23 |

| % | 60.0% | 52.4% | 56.1% | ||

| Abroad | Count | 8 | 10 | 18 | |

| % | 40.0% | 47.6% | 43.9% | ||

| Total | Count | 20 | 21 | 41 | |

| 100.0% | |||||

Note. Chi2 = 0.4; p = 0.62.

To establish whether the surplus of positive TTs was related to prior vaccination, questions were asked about the background of vaccination with BCG. 63.4% said that they had been vaccinated with BCG and 24.4% did not know their vaccination status. A small percentage (12.2%, 5 inmates) declared that they had not been vaccinated with BCG (χ2 = 21.19, p = 0.006 (Table 4).

Table 4. Contingency table of BCG vaccine/TT+

| TT | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-14 mm | 15-19 mm | 20-24 mm | 25-29 mm | More than 30 mm | ||||

| BCG vaccine | No | Count | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| % | 13.3% | 7.7% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 12.2% | ||

| Yes | Count | 9 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 26 | |

| % | 60.0% | 61.5% | 90.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 63.4% | ||

| Don’t know | Count | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 10 | |

| % | 26.7% | 30.8% | 10.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 24.4% | ||

| Total | Count | 15 | 13 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 41 | |

| % | 100.0% | |||||||

Of the 20 inmates with false positive TTs, 70% were vaccinated and 20% were unaware of the vaccination status. As regards the positive QFC cases, 57.1% were vaccinated with BCG and 28.6% did not know if they had been vaccinated (χ2 = 0.72, p = 0.69) (Table 5).

Discussion

Recent treatment of tuberculosis infection is based on the higher risk of progression of the active disease in the first years after primary infection. According to the recommendation, treatment for LTBI should be offered to anyone with a recent shift in a TT or IGRA, contact with a patient with pulmonary and/or laryngeal TB, a ≥5 mm TT or positive IGRA, but only after ruling out the active disease8.

The growing number of inmates who come from regions with a high prevalence of TB and the fact the inmates have been living in close quarters since 2000 have led to the implementation of programmes that focus mainly on the early detection of TB with highly effective tools3,13.

One of these is the TT, which has acted as a guide in managing LTBI. However, the use of QFT for screening LTBI is not widespread, although the number of inmates with false TT positives may be high11. It is therefore important to correctly select the candidates for LTBI treatment, given that the adverse effects and adherence to LTBI treatment amongst inmates often impose limits on the success and completion of this prophylaxis.

In our experience, only half of the 41 patients really had a positive QFT. Although the sample is a small one, the data suggests that QFTs would help to identify inmates who really need LTBI treatment.

The average age of the inmates is 41 years (40-59), which matches the average age of the Spanish prison population9,11.

Unlike other descriptive studies9,14, we observed a slight increase in the proportion of Spanish inmates with positive QFT when compared to foreigners, but this observation could be explained by extrinsic factors in prison policies, such as displacements of inmates to other prisons due to changes of location of their families to enable the inmate to keep in contact with them. Furthermore, Burgos is not a province with a large migratory flow when compared to the prisons of Alicante, Barcelona, Madrid, etc.

As regards the vaccination status, it was found that most inmates were vaccinated or were unaware of their status, which is a factor that might play a part in the false positives of the TT test, but which is irrelevant when the QFT test is carried out.

It was found that the values of the TT+ associated with the appraisal made by the physicians are insufficient for establishing LTBI chemoprophylactic treatment. The adverse effects of the LTBI treatment are reason enough for inmates to abandon or disregard the regimen, and so correctly selecting the candidates is greatly appreciated in prisons. Only a small percentage of the 41 inmates who had been diagnosed with LTBI from a TT+ were actually positive when they were tested with the QFT.

In 2005, after American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved QFT-G, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) held a meeting with consultants and researchers with experience in the field, to review the scientific evidence and clinical experiences with QFT-G. The CDCs concluded that QFT-G can be used in all the situations in which TTs are currently being used, including contact research, evaluation of recently arrived immigrants, and at health and social service centres such as prisons where there is a higher prevalence of TB9.

IGRAs are very promising tests and have a good specificity, but the discordance between a positive TT and the QFT-G depends on variables such as age, nationality and on whether the subject is vaccinated or not. Longitudinal studies are needed to define the predictive value of this type of test in a healthcare population such as prisons9. Some studies suggest that one QFT test, or one combines with a TT, is a sure way of diagnosing the existence of LTBI, and that using this approach will contribute towards a more specific selection of individuals who require preventive treatment15,16.

Other studies have come to similar findings: In a cross-sectional study of cohorts in the prisons of New York City (USA) that included 35,090 inmates, IGRA was used as a screening method and high screening rates and low indeterminate results were found17.

Another recent experience in the USA showed that the use of IGRA in the prison population is a feasible option. 403 (74.6%) foreign inmates in a prison were screened for LTBI and 10.4% were found to be positive18.

According to the findings of this study, the inclusion of QFT in the diagnostic algorithm for LTBI in the prison setting would be of great benefit, since it would help in the process of selecting patients who actually have LTBI and need treatment with isoniazid, thus saving on unnecessary treatment, potential associated toxicity, analytical controls and marginal costs. This study therefore suggests that the recommendations currently in force on prison health should be updated7,14.