Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones

versión On-line ISSN 2174-0534versión impresa ISSN 1576-5962

Rev. psicol. trab. organ. vol.25 no.1 Madrid abr. 2009

Effects of Interviewee's Job Experience and Gender on Ratings and Reliability in a Behavioral Interview

El Efecto de la Experiencia Laboral y del Género de los Entrevistados sobre las Valoraciones y Fiabilidad de una Entrevista Conductual

Beata Choragwicka

University of Santiago de Compostela

The author is a Ph.D. candidate with a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Research and Innovation and Science (FPU, AP2005-3807).

ABSTRACT

In this paper, the potential unfairness when using a behavior description interview (BDI) is analyzed. Twelve interviewees (6 experienced and 6 inexperienced ones, half of them men and the other half women) were assessed using a BDI. The average scores of participants and the interrater reliability coefficients when using 12 or 6 raters were calculated. Statistically significant differences were not found between experienced and inexperienced interviewees, or between male and female ones. The implications of these findings in the use of the BDI for personnel selection processes are discussed.

Key words: behavioral interview, unfairness, selection, experience, gender.

RESUMEN

En este artículo se analiza si el uso de la entrevista de descripción de conducta (EDC) puede implicar discriminación indirecta. Doce entrevistados, 6 con previa experiencia laboral y 6 sin experiencia, la mitad de ellos hombres y la mitad mujeres, fueron evaluados mediante una EDC. Se han calculado las puntuaciones medias de los entrevistados, al igual que la fiabilidad interjueces de la entrevista, utilizando un panel de 12 y de 6 evaluadores. No se han encontrado diferencias significativas entre los entrevistados con y sin experiencia laboral previa, al igual que entre hombres y mujeres. Se debaten las implicaciones de estos resultados para el uso de la EDC en los procesos de selección de personal.

Palabras clave: entrevista conductual, discriminación, selección, experiencia, género.

During 20th century, employment interview was not accepted by researchers and practitioners without controversy, despite being the most popular method in personnel selection (Harris, 1989; McDaniel, Whetzel, Schmidt, & Maurer, 1994; Salgado & Moscoso, 2002). A stormy debate around employment interview originated when some reviews demonstrated that unstructured interview showed low reliability coefficients and practically no validity for predicting job performance (Arvey & Campion, 1982; Hunter & Hunter, 1984; Mayfield, 1964; Reilly & Chao, 1982; Schmitt, 1976; Urlich & Trumbo, 1965; Wagner, 1949; Wright, 1969). The controversy was attenuated when investigations carried out during the 80's and 90's showed that highly structured interviews predicted performance very well, showing validity coefficients similar to the validity coefficients of the best personnel selection procedures (Campion, Palmer & Campion, 1997; Huffcutt & Arthur, 1994, Mc Daniel et al., 1994; Salgado & Moscoso, 2002; Wiesner & Cronshaw, 1988).

A new issue started in the early 80's with the development of new interview types, grouped by Salgado and Moscoso (2002) under the label of structured behavioral interview (SBI). The SBI group includes structured interviews such as behavior description interview, situational interview, multi-modal interview, and job analysis based interview (Campion, Pursell, & Brown, 1988; Janz, 1982, 1989; Latham, Saari, Pursell, & Campion, 1980; Schuler & Funke, 1989). In the last fifteen years, the most widely discussed aspect was whether different modalities of SBI are better or worse predictors of job performance than previous interview types (e.g. unstructured or semi-structured interviews) and whether or not there are differences among them. The researchers were primarily concerned with the psychometric properties of the two most popular SBI's types: situational interview (SI) and behavior description interview (BDI). A relevant point of this debate was the theoretical basis of these two interview models: stress on the candidate's intentions for the SI, versus information about past behavior in the case of BDI. The SI is based on the goal-setting theory proposed by Locke (1968). Thus, the developers of the situational interview (Latham et al., 1980) presume that interviewees' behavior is influenced by their intentions and this is reflected in candidate's job performance. For its part, the BDI is based on the principle that the best predictor of future behavior is past behavior (i.e. behavioral consistency principle). From a practical point of view, candidates respond to the hypothetical dilemmas of the specific job situations in the case of SI (Latham et al., 1980), whereas in the case of BDI (Janz 1977, 1982, 1989), candidates refer their past experiences in a range of circumstances that are similar to the ones that he or she might find at work. Both SBI and BDI are based on a job analysis and they use the technique of critical incidents (Flanagan, 1954) for developing questions and scales for assessing interviewee's responses. Interestingly, recent metaanalytic and empirical studies suggested that the BDI is slightly better predictor of job performance than the SI is (Huffcutt, Weekley, Wiesner, Degroot, & Jones, 2001; Krajewski, Goffin, McCarthy, Rothstein, & Johnston, 2006; Pulakos & Schmitt, 1995; Taylor & Small, 2002).

Together with the debate as to whether SI or BDI is a better predictor of job performance, another issue was raised. Some SI-oriented researchers suggested that because BDI is centered on past behavior, it could have unfair effects on candidates without job experience (Latham, 1989; Latham & Saari, 1984). These researchers speculated that BDI would put inexperienced candidates in a relatively weaker position compared with experienced candidates, and this, in turn, could lead to not giving the inexperienced interviewees the opportunities to gain new abilities and knowledge needed to accomplish the job in question. According to those researchers, inability to respond to pastbehavioral questions would not necessarily mean that inexperienced candidates are incompetent and unable to perform job related tasks if they were given the opportunity of employment. In reaction to this criticism, BDI-oriented authors (Janz, 1977, 1982, 1989; Janz, Hellervik & Gilmore, 1986) indicated that it is feasible to formulate behavior description questions referring to nonoccupational contexts that remain similar to job related situations. Indeed, this would increase amount of work needed for developing the BDI because two parallel versions of every BDI should be created. However, it would also constitute an effective counterargument to the assumed discrimination and unfairness against inexperienced candidates when using pastbehavioral questions. In spite of all, this practical suggestion did not resolve the doubts of some researchers. For example, Rynes (1993) concluded that candidates reckon that their non-job-related responses, which mostly consist of educational and home environmental experiences, would never be recognized by interviewers in the same way as work-based behaviors. Nevertheless, some researchers have demonstrated that the BDI is not biased (e.g. Pulakos & Schmitt, 1995), so any further conclusions should be drawn carefully.

The review of the content characteristics and psychometric properties of the SBI also implies examining if there is any evidence of a possible gender-based discrimination in this type of job interview (Choragwicka & Moscoso, 2007; Sáez Lanas, 2007; Salgado, Gorriti & Moscoso, 2007). The gender biased characteristics of selection procedures are nowadays widely discussed on scientific and professional grounds. At present, a major concern of all selection procedures' developers is that these tools should be fair and unbiased, especially when considering candidates' age, gender, race, and nationality. Furthermore, in the majority of democratic countries and especially in the European Union (EU) member countries (see Myors et al., 2008), legislation exists or is being prepared in order to guarantee fair selection methods for all group of applicants. There are legal requirements that procedures used in process of personnel selection cannot discriminate against some candidates because of their individual characteristics. For the SBI, a consequence of this is that neither validity nor reliability of this procedure should be affected when assessing experienced versus inexperienced candidates, male versus female candidates or national versus foreign candidates. For this reason, researchers interested in the SBI were attempting to demonstrate that decisions based on the SBI instrument are fair, and a considerable number of qualitative and quantitative studies on this subject was conducted to examine this issue (e.g. Huffcutt & Roth, 1998; Latham & Skarlicki, 1996, Pulakos & Schmitt, 1995; Taylor & Small, 2002).

In this paper, I analyze whether the responses of experienced interviewees are overestimated when using a BDI. Subsequently, I examine to what extent raters agree with their scores when assessing candidates, and whether the work-based responses of experienced candidates are scored higher than the educational and home environmental responses of inexperienced interviewees. Furthermore, I also verify whether the interviewees' gender is related to any statistically significant differences in the average scores and the reliability of the instrument. The following hypotheses are advanced:

H1. Previous job experience affects both the average score of the interviewees and the interrater reliability of the BDI.

1.1. The interviewees with previous job experience will score higher than inexperienced ones, when being assessed using a BD interview.

1.2. The interrater reliability coefficient of the BDI with the experienced interviewees will be larger than in the case of inexperienced interviewees.

The prediction 1.1 is based on the conjecture that the BDI negatively discriminates inexperienced interviewees, as suggested by some authors (Di Milia & Gorodecki, 1997; Latham, 1989; Latham & Saari, 1984; Pulakos & Schmitt, 1995). I have checked this hypothesis by comparing the average scores of both groups of interviewees. Furthermore, the underestimation of the responses of the inexperienced interviewees can also indicate that interviewers (raters) have difficulty to assess interviewees' past-behavioral responses applied to non-job-related situations. As the result, it can be deduced that the interrater agreement will decrease, as it is stated in prediction 12.

H2. The interviewee's gender does not affect either the individual score or interrater reliability of the BDI.

2.1. There will be no significant differences between men and women interviewee groups when considering their score.

2.2. There will be no significant differences between men and women when considering the interrater reliability of the BDI.

The prediction 2.1 was based on the studies founding that BDI is a valid predictor of job performance for a range of jobs (Huffcutt et al., 2001; Krajewski et al., 2006; Pulakos & Schmitt, 1995; Taylor & Small, 2002). I assume that this interview modality, that was proved to have high psychometric properties, cannot exhibit gender-discriminatory effects that hitherto would not have been discovered.

The prediction 2.2 continues arguments raised in the prediction 2.1. The comparable average scores received by the interviewees of both genders would suggest that the raters agree to the same extent when rating male and female interviewees and the differences between interrater reliability coefficients of interviews with men and women will not be statistically significant.

Method

Sample

Interviewees. Six men and six women were assessed using a BDI interview developed to recruit waiters and waitresses. In each group, half of the members had previous job experience and the other half had none. Their ages varied from 21 to 43 years old. Eight of them were Spanish and four came from other countries (two were members of the experienced group and remaining two of the inexperienced one). The interviewees were not participating in a real selection process as this sample was created for this study only, and all experienced interviewees were already employed as waiting stuff.

Raters. Three men and nine women formally trained but with no previous experience in the evaluation of interviewees using the BDI, all of them Spanish.

Procedure

Instrument. In order to test the stated hypotheses, a BDI for waiting stuff was developed according to the rules indicated by Janz (1977, 1982, 1989) and following some modifications proposed by Moscoso and Salgado (2001). The interview was based on a total amount of 137 critical incidents, characteristic of the job of waiter/waitress and collected from incumbents, supervisors, and clients of the restaurant business. The complete version of this interview contained 14 questions referring to 10 general aspects of waiting staff duties. In the later part of the experiment a shortened version of the original interview was developed with the objective to be applied in the study of interrater reliability. The final version of the instrument contained 10 questions for the experienced interviewees and nine for the inexperienced ones, and these questions reflected seven dimensions: politeness, stress resistance, responsibility, attentiveness at work, work knowledge, companionship, and discretion. Afterwards, the content validity of the instrument was examined using the Content Evaluation Panel method proposed by Lawshe (1975, see also Choragwicka & Moscoso, 2007).

Interviews. Twelve interviews were carried out by the same interviewer and a digital voice recorder was used. By these means, the voice of the interviewee could be heard but his or her physical appearance could not be seen. This was done to avoid bias based on physical attractiveness and to ensure that only the responses to the interviewer's questions would be taken into account.

Rating. Once all interviews were recorded, a panel of 12 raters was created. Raters were informed about the SBI characteristics, the different SBI's types and about the particularities of the BDI modality. The training session also consisted of information about how the interview questions were developed and how they are related to the waiter occupation. Raters were also trained on the evaluation technique, i.e. how to filter useful information and use behavioral anchored rating scales (BARS). They also received a manual containing specific interview instructions, both interview versions (for experienced and inexperienced interviewees), descriptions of the dimensions with five-point BARS for each question, and a standardized questionnaire for each interviewee.

Four of the interviewees were rated by all 12 raters and the rest of them by panels of six raters (four interviewees by a panel of six raters, and the other four interviewees by a panel of the other six raters). No more than two interviewees were rated during every session. The members of the panel worked separately and could not consult others about their ratings. They were asked to make notes when listening to the interviews and to rate each person on each question at the end of the procedure.

Previous analyses. The interrater validity of the instrument was estimated using the prophecy formula of Spearman-Brown. An average adjusted interrater reliability coefficient of .78 was found, similar to the .75 value obtained in the meta-analyses of Conway, Jako and Goodman (1995) and Salgado and Moscoso (2002). Subsequently, the average scores of group of experienced and inexperienced interviewees and the mean interrater reliability coefficient for both groups were calculated and compared using the Student's ttest. Finally, the same procedure was repeated for both male and female interviewees.

Results

Interviewees' experience and the interview rating

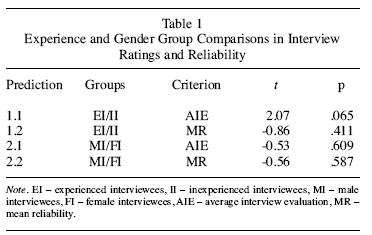

The mean scores of interviewees with previous job experience and without experience were contrasted. An average score of 4.18 (SD=.28) was found for interviewees with previous job experience and a score of 3.69 (SD=.50) for those with no job experience. However, Student's ttest statistic gives no evidence to reject the null hypothesis of equal means (see Table 1).

Interviewees' experience and the reliability of the instrument

Student's t-test was used to test whether a significant difference existed between the average interrater reliability coefficient in the cases of interviews with experienced and with inexperienced interviewees. The reliability coefficient of the interviews with experienced interviewees was .69 (SD=.21) and that of BDI with inexperienced interviewees .78 (SD=.14). Nevertheless, the differences between the average results of both groups were not found to be significant (see Table 1).

Interviewees' gender and the interview rating

The equivalence between the mean score of men and women was also statistically examined by Student's t-test. The male interviewees were rated on average 3.86 (SD=.63) and female interviewees on average received the score of 4.01 (SD=.27). No significant difference was found (see Table 1).

Interviewees' gender and the reliability of the instrument

Finally, the interrater reliability coefficients of interviews with men and with women were contrasted. The interrater reliability coefficient of BDI with male interviewees resulted in a slightly lower average (M=.70, SD=.22) than that of BDI with female interviewees (M=.76, SD=.14). Nevertheless, Student's t-test demonstrated that this dissimilarity was not statistically significant (see Table 1).

Discussion

The results of this study do not confirm the initial hypothesis of the potential bias and unfairness when BDI is used for assessing inexperienced interviewees. Data gathered for this paper does not provide support confirming neither prediction 1.1 nor the prediction 1.2. On average, interviewees with no previous job experience were not rated with lower mean score than the experienced candidates. Also, the average interrater reliability coefficient was not significantly lower for the inexperienced interviewees. In addition, the average reliability is even slightly larger for the interviews with the inexperienced interviewees than for interviews with experienced candidates, although Student's ttest demonstrated that this difference has no statistical significance.

On the other hand, the results of the interviews conducted for this study confirm the two predictions derived from the second hypothesis. The scores of both women and men were not underestimated, and furthermore any significant differences between the average reliability coefficients of BDI with male and female interviewees were found.

Another added-value of this study results from the relatively large number of raters (6 or 12) that were used to assess the reliability of the interviews (despite a relatively small number of interviews). To the best of my knowledge such number of raters was not used so far in any study of a similar type.

Apart from its positive aspects, this study also has some limitations. One of these limitations is the use of inexperienced raters and their relatively short period of training. It, however, did not significantly obstruct the results of this study, and the average reliability of the BDI used in this study (.78) is slightly higher than the one found for the BDIs in the metaanalytic studies (.75) (Conway et al., 1995; Salgado & Moscoso, 2002). Nevertheless, there are studies where higher values were found when using certified and experienced raters (e.g. Salgado, Moscoso & Gorriti, 2004). Secondly, the characteristics of the assessed occupation might have influenced the results when differences between men and women were considered. In Spain, the occupation of a waiting staff is not considered to be particularly masculine or feminine, but is regarded as suitable for both genders. For that reason, when using a BDI, it would be useful to examine whether men or women are discriminated against when applying for a profession socially considered exclusive for the opposite sex. Moreover, the same comparative procedure should be repeated with Spanish and other nationalities interviewees. However, this analysis could not be carried out in this study because foreign interviewees were underrepresented. Finally, not only content- but also criterionrelated evidence of validity of the instrument ought to be measured. In this study, it was impossible as the interviewees were not participating in a real selection process and members of the experienced group were already employed as waiters. Nevertheless, as the reliability and content validity of the interview were measured and found to be appropriate, it is possible to suppose that its criterion-related validity should be similar to the value that was found for the BDIs in the meta-analytic reviews (Salgado, 1999; Salgado & Moscoso, 2002).

The findings of this study have also implications for the practice of personnel election, as they provide practitioners with strong support for using this interview type in the professional practice. The BDI resulted to be a reliable method of assessment, and did not discriminate against interviewees because of their gender or lack of previous job experience. These results show the significance and importance of the SBIs, particularly of its BDI form, in the personnel selection processes. First, we may assure that choosing a BDI as an assessment tool we will guarantee a fair selection process for both male versus female and experienced versus inexperienced candidates. Furthermore, we may be certain that educational and home environmental experiences of inexperienced interviewees will not be underestimated, since both interview versions have given comparable results in terms of average score and reliability.

In summary, in this study the potential unfairness when using a behavior description interview (BDI) was analyzed. It was supposed that inexperienced interviewees' responses may be underestimated as suggested by some authors (Di Milia & Gorodecki, 1997; Latham, 1989; Latham & Saari, 1984; Pulakos & Schmitt, 1995). Moreover, the difficulty to assess interviewees' past-behavioral responses applied to non-job-related situations was expected to cause lower reliability for these interviews. On the other hand, I supposed that gender would not affect either the individual score or interrater reliability of the BDI. No empirical support was found for the conjecture that the average scores of interviewees or the mean reliability coefficients were affected in the cases of experienced and inexperienced groups. Furthermore, the results confirmed gender fairness of a BDI.

References

Arvey, R. D., & Campion, J. E. (1982). The employment interview: a summary and review of recent research. Personnel Psychology, 35, 281-322. [ Links ]

Campion, M. A., Palmer, D.K, & Campion, J.E. (1997). A review of structure in the selection interview. Personnel Psychology, 50, 1-64. [ Links ]

Campion, M. A., Pursell, E. D., & Brown, B. K. (1988). Structured interviewing: Raising the psychometric properties of the employment interview. Personnel Psychology, 41, 25-42. [ Links ]

Choragwicka, B., & Moscoso, S. (2007). Validez de contenido e una Entrevista Conductual Estructurada. / Content validity of a Structured Behavioral Interview. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones. Special Issue: Advances in occupational performance and personnel selection research in Europe, 23, 75-92. [ Links ]

Conway, J. M, Jako, R. A., & Goodman, D. F. (1995). A meta-analysis of interrater and internal consistency reliability of selection interviews. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 565-579. [ Links ]

Di Milia, L., & Gorodecki, M. (1997). Some factors explaining the reliability of a structured interview system at a work site. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 4, 193-199. [ Links ]

Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incidents technique. Psychological Bulletin, 51, 327-358. [ Links ]

Harris, M. M. (1989). Reconsidering the employment interview: a review of recent literature and suggestions for future research. Personnel Psychology, 42, 691-725. [ Links ]

Huffcutt, A. I., & Arthur, W. Jr. (1994). Hunter and Hunter (1984) revisited: Interview validity for entry-level jobs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 184-190. [ Links ]

Huffcutt, A. I., & Roth, P. L. (1998). Racial group differences in employment interview evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 179-189. [ Links ]

Huffcutt, A. I., Weekley, J., Wiesner, W. H., Degroot, T. & Jones, C. (2001). Comparison of situational and behavior description interview questions for higher-level positions. Personnel Psychology, 54, 619-644. [ Links ]

Hunter, J. E., & Hunter, R.F. (1984). Validity and utility of alternative predictors of job performance. Psychological Bulletin, 96, 72-98. [ Links ]

Janz, T. (1977). The behavior based patterned interview: an effective alternative to the warm smile selection interview. Proceedings of the Annual Conference of Canadian Managerial Association. [ Links ]

Janz, T. (1982). Initial comparisons of patterned behavior description interview versus unstructured interviews. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67, 577-580. [ Links ]

Janz, T. (1989). The Patterned Behavior Description Interview: The best prophet of the future is the past. En R. W., Eder & G. R., Ferris (Eds.). The employment interview: Theory, research and practice (pp. 158-168). Beverly Hills, Sage. [ Links ]

Janz, T., Hellervik, L., & Gilmore, D. C. (1986). Behavior description interviewing: New, accurate, cost-effective. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

Krajewski, H. T., Goffin, R. D., McCarthy, M. J., Rothstein, M.G., & Johnston, N. (2006). Comparing the validity of structures interviews for managerial levels employees: Should we look to the past or focus on the future? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79, 411-432. [ Links ]

Latham, G. P. (1989). The reliability, validity and practicality of the situational interview. En R. W., Eder, & G. R., Ferris (Eds.). The employment interview: Theory, research and practice (pp. 169-182). Beverly Hills, Sage. [ Links ]

Latham, G. P., & Saari, L. M. (1984). Do people do what they say? Further studies on the situational interview. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69, 569-573. [ Links ]

Latham, G. P., Saari, L. M., Pursell, E. D., & Campion, M. A. (1980). The situational interview. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65, 422-427. [ Links ]

Latham, G. P., & Skarlicki, D. (1996). Criterion-related validity of the situational and patterned behavior description with organizational citizenship behavior. Human Performance, 8, 67-80. [ Links ]

Latham, G. P., Saari, L. M., Pursell, E. D., & Campion, M. A. (1980). The situational interview. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65, 422-427. [ Links ]

Lawshe, C. H. (1975). A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology, 28, 563-575. [ Links ]

Locke, E. A. (1968). Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 3, 157-189. [ Links ]

Mayfield, E.C. (1964). The selection interview: A re-evaluation of published research. Personnel Psychology, 17, 239-260. [ Links ]

McDaniel, M. A., Whetzel, D. L., Schmidt, F. L., & Maurer, S. D. (1994). The validity of employment interviews: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 599-616. [ Links ]

Moscoso, S., & Salgado, J. F. (2001). Psychometric properties of a structured interview to hire private security personnel. Journal of Business and Psychology, 16, 51-59. [ Links ]

Myors, B., Lievens, F., Schollaert, E., Van Hoye, G., Cronshaw, S. F., Mladinic, A., et al. (2008). International perspectives on the legal environment for selection. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 1, 206–246. [ Links ]

Pulakos, E. D., & Schmitt, N. (1995). Experienced-based and situational interview questions: Studies of validity. Personnel Psychology, 48, 289-308. [ Links ]

Reilly, R. R., & Chao, G. T. (1982). Validity and fairness of some alternative employee selection procedures. Personnel Psychology, 35, 1-62. [ Links ]

Rynes, S.L. (1993). Who's selecting whom? Effects of selection practices on applicant attitudes and behavior. In N. Schmitt & W. C. Borman (Eds.), Personnel Selection in Organizations. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Sáez Lanas, J. (2007). Diseño y validación de una Entrevista Conductual Estructurada para la selección de agentes de policía local. / Design and validation of a Structured Behavioral Interview for selection of local police officers. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones. Special Issue: Advances in occupational performance and personnel selection research in Europe, 23, 57-74. [ Links ]

Salgado, J. F. (1999). Personnel selection methods. En Cooper C. L. & Robertson I. T (Eds.). International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 12 (pp. 1-53), London, UK, John Wiley and Sons. [ Links ]

Salgado, J. F. (2007). Análisis de utilidad económica de la Entrevista Conductual Estructurada en la selección de personal de la administración general del País Vasco. / Utility analysis of the Structured Behavioral Interview within the selection of personnel for the general administration of the Basque Country. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones. Special Issue: Advances in occupational performance and personnel selection research in Europe, 23, 139-154. [ Links ]

Salgado, J. F., Gorriti, M., & Moscoso, S. (2007). La entrevista conductual estructurada y el desempeño laboral en la Administración Pública española: propiedades psicométricas y reacciones de justicia. /The structured behavioral interview and job performance in the Spanish Public Administration: psychometric properties and fairness reactions. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones. Special Issue: Advances in occupational performance and personnel selection research in Europe, 23, 39-55. [ Links ]

Salgado, J. F., & Moscoso, S. (2002). Comprehensive meta-analysis of the construct validity of the employment interview. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 11, 299-324. [ Links ]

Salgado, J. F., Moscoso, S., & Gorriti, M. (2004). Investigaciones sobre la Entrevista Conductual Estructurada (ECE) en la Selección de Personal en la Administración General del País Vasco: Meta-análisis de la Fiabilidad, Revista de Psicología de Trabajo y Organizaciones, 20 (2), 107-139. [ Links ]

Schmitt, N. (1976). Social and situational determinants of interviews decisions: Implications for the employment interview. Personnel Psychology, 29, 79-101. [ Links ]

Schuler, H., & Funke, U. (1989). The interview as a multimodal procedure. In R. W. Eder & G. R. Ferris (Eds.), The employment interview: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 183-192). Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Urlich, L., & Trumbo, D. (1965). The selection interview since 1949. Psychological Bulletin, 63, 100-116. [ Links ]

Taylor, P. J., & Small, B. (2002). Asking applicants what they would do versus what they did do: A meta-analytic comparison of situational and past behavior employment interview questions. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 75, 277-294. [ Links ]

Wagner, R. (1949). The employment interview: A critical review. Personnel Psychology, 2, 17-46. [ Links ]

Wiesner, W. H., & Cronshaw, S. F. (1988). The moderating impact of interview format and degree of structure on interview validity. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 61, 275-290. [ Links ]

Wright, O. R. Jr. (1969). Summary of research on theselection interview since 1964. Personnel Psychology, 22, 391-413. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Beata Choragwicka

Facultad de Psicología

Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, Campus Sur

15872 Santiago de Compostela, Spain

E-mail: beata.choragwicka@usc.es

Recibido: 18/12/2008

Revisado: 20/2/2009

Aceptado: 24/2/2009